Kristopher Jansma’s Novel Approach

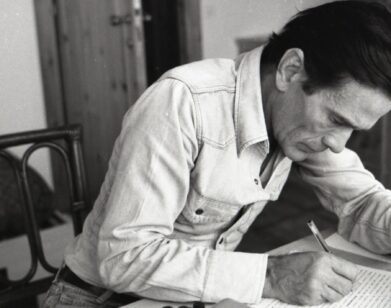

ABOVE: KRISTOPHER JANSMA. IMAGE COURTESY OF MICHAEL LEVY

On a brisk January afternoon, we met with Kristopher Jansma, a longtime friend, at the Washington Hotel to discuss his debut, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, out this month with Viking/Penguin. The hotel inspired a fictional setting, thinly disguised as The Washington, where the main characters from his debut novel meet every Sunday for a jazz brunch.

Leopards has been lauded by Booklist and selected by Barnes & Noble as a Summer 2013 Discover Pick. Flavorwire named Jansma as one of 50 up and coming New York culture makers in 2013. After three failed novels, Jansma decided to break every rule he’s been taught—don’t write about writers, don’t write what you know, don’t write what you don’t know. He learned and unlearned these rules at Johns Hopkins and Columbia, where he got his undergraduate and graduate degrees, respectively; and he helps his students break them as adjunct professor of creative writing at Manhattanville College and SUNY Purchase.â?? Jansma also writes a column on Literary Artifacts for Electric Literature and has been published BOMB Magazine, The Believer and The Millions, among other places.

ERIKA ANDERSON: On the way to the jazz brunch, your narrator says, “… in our era of anthemic dance beats, power chords, and casually rhymed profanities, jazz music has become quaint and old-fashioned, appreciated only by those who were born too late—namely, the three of us.” Have you ever felt that way?

KRISTOPHER JANSMA: I had some ideas of New York as Jazz Age art, that there would be these bohemian get-togethers of F. Scott Fitzgerald-type people. But one of the reasons I wanted to focus on jazz music was that the way I was writing the book was very improvised. I was trying to break a lot of the rules I had been taught as a writer.

ANDERSON: What rules did you break?

JANSMA: I had always been told you should never write about writing, you should never write about writers. Last semester, a student wrote this incredible story about a breakup, but part of the story was about writing a story. One of the first responses in the workshop was, “Well, you can’t write a story about writing.” And I asked, “Why can’t you do that?” He said, “Everybody knows you can’t do that.” I said, “I don’t know that. That’s a dumb rule.” “It’s only going to be interesting to other writers. It won’t be interesting to people who don’t write.” I said, “That’s not true, it’s a great story. Even if readers aren’t writers, they tell each other stories; they process great books the same way that we all do. Some of us sit down at a typewriter or computer and write out what we’re feeling, other people call up a friend. We all go through the storytelling process to make sense of it all.” I have two characters who are writers, with this jealous, competitive relationship, and first I thought I should have them be architects or painters to disguise that. But I’ve read books that do that, and it’s so obvious that they’re really wanting to write about writers and they’re trying to pretend it’s really about something else. Once it was all finished and I was sending it around, I had several agents tell me there’s no way anyone’s going to buy a book about writers. One agent said, “I found that editors have an allergy to books about writing.”

ANDERSON: Those absolute rules are tricky. A teacher once told me, “Don’t ever write about your thoughts. No one wants to know what you’re thinking.” [laughs]

JANSMA: [laughs] What else do you have? I think it’s something you start to realize after you’ve taken a lot of workshops, talked to different professors and writers: They all give you conflicting advice, and they’re all absolute rules. One guy will tell you, “You have to write what you know, don’t ever write about anything that’s made up, because it won’t be authoritative.” Then other people will tell you it has to be fiction; if it’s not, if it’s based on reality, then it’s really nonfiction hiding. I pretty much concluded that the only consistent thing was that no one really agreed about anything. You can really get away with anything as long as you work at it.

ANDERSON: Is that your goal?

JANSMA: I think so. If I find myself worrying that there’s something I want to do that I’m not allowed to do, that I’m not supposed to do, that usually means that I have to work harder at it to make it work.

ANDERSON: Was there any good advice amidst all those conflicting rules?

JANSMA: One of the best pieces of advice I ever got was from a professor who asked, “Are you sure you want to do this?” I said, “Yeah, I’ve always wanted to be a writer.” “Just remember that if you can see yourself being happy doing anything else other than this, you should do that instead.” At the time I was crushed by it, thinking he was telling me, “You’re not that good, try something else.” But what he was actually trying to say is that it’s a hard and frustrating process, and there’s a lot of failure in the way of getting something done. So why not avoid that if you can? If you can be perfectly happy selling computers, do that. Don’t just be a writer because you like reading.

ANDERSON: Your novel reads somewhat like a detective story. Part of the mystery is that your narrator lacks a name.

JANSMA: I’ve always really liked unnamed narrators. When you’re reading a first-person story, you feel this connection with the writer right away, and it almost feels like the writer’s confessing something to you intimately. You can make them feel like they can trust you. You tell them everything and then all the sudden let them know, “Actually I haven’t told you everything.” You can say, “Even this is a fiction.”

ANDERSON: Speaking of fiction, your narrator works as a plagiarist at one point, asking “What possible use will it be to [students] to deconstruct a Dickens novel when they’re merrily employed by some white-collar firm, overseeing the outsourcing of its customer service department to the east side of Bangladesh? Actually, a lot, probably.” What is the use? Jansma, defend education. [laughs]

JANSMA: [laughs] One of the first questions I ever got about the book from people at Penguin was, “Oh, you must not want your students to read this. You seem really down on higher education.” And I had to remind them that’s not how I feel—it’s the character. I always tell my students I think that learning to write well is one of the most useful skills that you could get out of college: the ability to communicate, the ability to argue, to persuade people. Reading a Dickens novel, you’re going to learn about the plight of the underprivileged, the privileges of the ruling class.

ANDERSON: The narrator meets an aspiring writer who says, “Oh, I’ve written a few chapters, but they’re not very good.”

JANSMA: “And by the way, would you read them?”

ANDERSON: And the narrator says, “I’m sure they’re great!” But he’s thinking, “I’m sure they’re terrible.” The narrator goes on: “The real thing—the true thing—takes more time and effort than most people would ever imagine. Whole productive lifetimes for a few hundred pages that most assuredly won’t outlive us.” Of all the lines in the book, did you relate to this line in particular?

JANSMA: It’s funny how often you’ll meet people and tell them, “Oh, I’m a writer,” and they’ll tell you, “I’ve always wanted to write a book.” Or, “I got this great story that somebody should write.” A lot of people think of writing as something that they’d love to do someday. But really good writing feels effortless. When I read Catcher in the Rye for the first time in high school, it really felt like J.D. Salinger sat down at a typewriter and said, “I’m just going to start talking, somebody write this down.” But it took J.D. Salinger 10 years to write that book.

ANDERSON: You said you always knew you wanted to be a writer. What’s the first thing you wrote?

JANSMA: The first book I wrote was in the fourth grade, called “The Pencil Thief.” Pencils kept getting stolen out of the desk. We built these elaborate mousetraps with paperclips and rubber bands so that if someone opened the desk without disarming it, it would throw a paperclip at them. In my book, two kids lay in wait to catch the pencil thief. When she appears, they get sucked into an alternate universe where pencils are building materials. But the girl was a reluctant accomplice—there was an evil pencil king who was forcing her to steal all the pencils and bring them back, and so the kids liberated her. I think I still have it somewhere.

THE UNCHANGEABLE SPOTS OF LEOPARDS IS OUT MARCH 21.