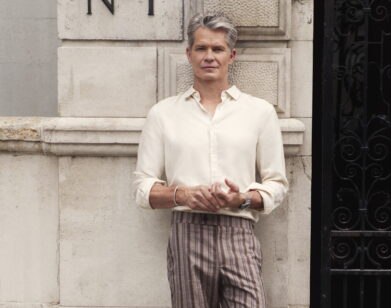

Christopher Bollen

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IN NEW YORK, APRIL 2015.

I’m convinced I was the only kid ever who had a Death on the Nile movie poster and a Murder on the Orient Express movie poster on his bedroom walls. CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN

Early on in Christopher Bollen’s bucolic gothic Orient (Harper)—a novel set in the seaside village of Orient on Long Island’s North Fork—the town’s lefty sage, Magdalena, drops some knowledge on the book’s prodigal heroine, Beth. “The Greeks used to say that gods and animals were born whole,” Lena says. “It is only humans who need to develop, that they become complete only with the help of a community. It’s the state of that community that can turn a human into a god or a beast.”

The community members in question become the main players, the victims, suspects, and amateur sleuths of Bollen’s murder mystery. (No gods among them, but there are a few bizarre beasts made wholly monstrous, perhaps, by the super-secretive government laboratories on nearby Plum Island.) Following the young drifter and former foster kid Mills as he makes his way into their deceptively stable homes and rapidly unraveling lives, Bollen’s portraiture of the town’s lifers, of the suburban mothers, the newcomers, nouveau riche artists, and arrivistes, has the richness and generosity of Northeastern fiction gone by, as if Cheever’s swimmer somehow crossed both the Sound and time.

But then the bodies drop-one by one, and then by the handful, with mounting theatricality, as Cheever-ish character study gives way to claustrophobia and a coiling menace not unlike the sort made famous by Bollen’s great childhood hero Agatha Christie. When the carnage starts, no one is safe. More than once while reading, I sat straight up, laughing uncontrollably, in shock at a devilish twist or an unthinkable murder. And then I texted the author, in all my incredulous fury, “How could you!?”

I don’t pretend to be without bias here. Bollen (who is Interview‘s editor at large and, as such, keeper of house style, so he’ll appreciate that I mention his age: 39) is a trusted colleague, advisor, and one of my closest friends. He also happens to have written one of the more unique literary mysteries I’ve ever read. Not that I’m entirely surprised.

As he tells it, it was community that made this Cincinnati native whole. After moving to New York to study literature at Columbia, Bollen started working in magazines and found his people among the cool kids and downtowners (a milieu similar to that of his debut novel, Lightning People—which, like Orient, has a prodigious body count and a fondness for conspiracy theories). His graduate school came in the form of the dialogues he had with the great writers of the day, from Joan Didion to Toni Morrison, from Jay McInerney to Edmund White and Zadie Smith, while editing V magazine and then at Interview.

On a moody gray day in early April, as spring tried to persuade us to join in its wild hopefulness, Bollen and I tried for just such a dialogue. Eating nachos, perched in a window seat at a café a stone’s throw from where each of us lives in the East Village, we talked about first fears, and the aesthetics of murder.

CHRIS WALLACE: First, why Orient?

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: I had been going out to Orient for several years. Artist friends of mine have been renting houses out there since the early 2000s. Then a few years ago I was working on the edits for Lightning People, and some friends had bought an old clapboard house in the village. They’d stripped the interior, but they had to keep the exterior pristine because of the dictates of the historical board, which comes into play in Orient. But before they got to the renovations, they invited me to stay there alone for a week. I had never done that. I’ve never even done a residency. Every time I try to write on vacation, I fail miserably. But I rented a car, went out by myself, and it was so beautiful. By day—beautiful sword grass fields, and, beyond, the bay. It was so peaceful. Then night crept in …

WALLACE: [laughs] And you were scared to death.

BOLLEN: I had lived in New York since 1996, sometimes in the worst neighborhoods, without even locking my door half the time. But this darkness was so thick, so all encompassing. And the house was so old. At night the walls revealed claw marks. I was terrified. I knew I was being ridiculous. But I had never been by myself in the country before, as an adult or as a child. So I slept with a kitchen knife.

WALLACE: Which is just insane. But also, I get really scared when I’m in nature.

BOLLEN: Nature’s terrifying.

WALLACE: Was fear a factor in your childhood?

BOLLEN: I was a very scared child. My parents were great parents, but for some bizarre reason they allowed me to watch whatever I wanted on TV, we had cable. And I constantly watched horror movies.

WALLACE: Were the movies putting the ideas into your head? Or was it comforting to see, projected, what you were already afraid of?

BOLLEN: They were putting ideas in my head. I wouldn’t have been as terrified, but the weird thing was, I also really loved to watch them. The first horror movie I saw, in first or second grade, was My Bloody Valentine [1981], where there’s a deranged killer in a miner mask stalking a small coal town.

WALLACE: Jesus.

BOLLEN: It was the first movie on HBO when we got cable. Like, I just turned the TV on and there it was. To this day I still watch tons of horror. It must be about controlling or mitigating fears in a way, right?

WALLACE: Because if you’ve seen it so many times, it takes away the fear?

BOLLEN: Right. And, on the other hand, going out into the country after living in the city is a loss of control.

WALLACE: Murder mysteries and horror films are definitely about flirting with that loss of control. But then writing about murder is the exact opposite. It’s like masochist turned sadist.

BOLLEN: Totally.

WALLACE: And you’re having fucking fun killing people in Orient.

BOLLEN: Yeah, as a writer it’s exciting.

WALLACE: I don’t know if those are two sides of the same coin, but you clearly have both. You’re titillated by the fear part—or are at least drawn to master that fear—but you’re also turned on by acting it out.

BOLLEN: I wish Orient were even scarier. One day I want to write a full-on horror book. But, when it comes down to it, mystery makes more sense to me. There’s a structure to a detective story that I can easily understand. I understand playing that particular game. It’s like solving a puzzle. Or creating a puzzle. You find when you’re writing a detective story that you’re actually not trying to solve anything. You’re trying to stop the reader from solving the puzzle. Which also is maybe why I love chess and tennis—the volleying aspect, and the fact that your competitors’ reactions and motivations and bluffs come into the game itself. But maybe it was just very American boy of me to be fascinated by horror and serial killers and all that. I really was always on the side of the victim and not the killer—I identified with the one being chased, not the chaser—but I did watch Jason and Freddy and Michael Myers. But I also remember when I watched Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer [1990] at, like, age 15.

WALLACE: Good god.

BOLLEN: That scared the crap out of me. Because it didn’t operate inside the usual conventions of the horror genre in the way that I could accept. I can accept horny teenager counselors being murdered at camp. But I couldn’t accept the derangement of Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, which was that anyone could be murdered at any moment—whole families, with no build-up music and no meaning. It terrified me.

WALLACE: Which is precisely what I’ve been teasing you about with Orient. You create characters that are not disposable bimbos and then slaughter them. I’m still devastated. But I won’t spoil anything here.

BOLLEN: Isn’t that a funny thing about talking about a mystery? People are still issuing spoiler alerts about Gone Girl. I wonder when you can finally reveal that Tom Ripley gets away with killing Dickie Greenleaf in The Talented Mr. Ripley. Or that everyone on the Orient Express is guilty. That’s okay to say out loud, right? When does the solution move into public domain?

WALLACE: Well, the spell is still capable of delivering a thrill, its magic keeps. And if you give it away, you’re breaking the spell. But I’m curious about the aesthetics of murder and of mystery. Beyond the mastery or flirtation with fear, there is the sorting it out, a kind of hygienic-ness of restoring moral order to the mystery novel. Which is very apparent in Holmes or our beloved Poirot. When did you get into Christie?

BOLLEN: I was obsessed with Agatha Christie in sixth grade. I’m convinced I was the only kid ever who had a Death on the Nile [1978] movie poster and a Murder on the Orient Express [1974] movie poster on his bedroom walls. I would write all these detective stories in my room, total knockoffs of Agatha Christie, set in places I’d never been. A lot of them took place in Baghdad because I loved the way it sounded. I had no idea where it was. It could have been in Jamaica for all I knew. There were a lot of British aristocrats running around these stories, because that’s who I thought inhabited the world of murder mystery.

WALLACE: I think that is part of the allure, the glamour, the grandeur, and Victorian-ness of Agatha Christie. The way sex is repressed but people act out in their murders. In Orient, though, we’re in this debauched, permissive, decadent now. And, weirdly, that backdrop shows murder to be even more abhorrent, even more of an aberration than in Christie, where it is lumped in with all these other bestial human appetites.

BOLLEN: It’s true. As much as I adore Agatha Christie—and I think people make this claim about murder mysteries in general—it’s often a very conservative mode of storytelling. Most of her plots are about people who don’t have money wanting money from the elites. Usually it’s the greedy, climbing, new-money slimeball who wants to take from the aristocracy.

WALLACE: But that whole world, where people take trains to Istanbul, drinking tea from art deco china …

BOLLEN: [sighs] It’s heaven. Do you think the detective story is a conservative genre?

WALLACE: A hundred percent. You’re restoring moral order. Which is why detectives are asexual, virginal. They are knights of purity.

BOLLEN: Right, the restoration of the peace. I was reading that Auden piece, “The Guilty Vicarage,” recently, which is his essay on murder mysteries. It was published by Harper’s in 1948, and it’s not all that positive. He compares obsessively reading them to an addiction, like smoking or drinking, but he doesn’t deem them works of art. And one of his justifications is that once you know who committed the crimes, he has no interest in rereading them as stories. I totally disagree with that.

WALLACE: I reread and rewatch mysteries all the time.

BOLLEN: Also, going back to your point about the detective often being rather sexually hard to pin down, one of the two main characters in Orient is Mills, who is gay. There are several reasons why it was important for me that Mills be gay, but I think one of them was playing with that tradition of a detective like Sherlock Holmes or Poirot or Nero Wolfe being slightly hard to read sexually—in ways, they all read as gay. Which I think harkens as far back as the prophet Tiresias and this idea of having second sight connected with more complicated, uncertain sexualities. But of course Mills is also gay, because he’s an outsider in all sorts of ways.

WALLACE: There’s a natural, obvious question, which I have to ask. Orient is populated, largely, by artists. And there are some spectacularly theatrical murders. You’re inviting the comparison between artist and serial killer.

BOLLEN: Artist and criminal. That’s an old comparison.

WALLACE: But after I finished the book, I kept thinking about how similar an artist’s process is to a serial killer’s, the staging, the compulsion … How is it that some weird propagandist artist hasn’t crossed that bridge and turned serial killer?

BOLLEN: I know, it’s the last taboo. Provocateur as killer. And I also wonder why is it that so many of the movies and books that are detective stories are also the most aesthetically interesting? From Hollywood noirs to horror movies like The Shining [1980]. There’s something about fear and aesthetic that go hand in hand.

WALLACE: And in the Freudian scheme, death drive is the opposite of Eros …

BOLLEN: The death drive is parasitic. It runs off of other drives, leeching off of them.

WALLACE: That makes sense—the erotic charge serial killers, in movies anyway, get from their crimes. And serial killers, of course, are also usually virginal, like the dark mirror of the detective. You were raised Catholic. Do you have any holdover rituals or rites in your daily life?

BOLLEN: Well, I smoke cigarettes when I write, which is disgusting, but it really helps me.

WALLACE: That is the greatest tactic I’ve ever heard of though—only smoking at your writing desk.

BOLLEN: It’s chaining myself to the work and chain-smoking my way through a book. I just think, as writers, especially with a book that takes years to write, you sort of wake up every morning hoping and praying that you can make it work for the day. It can make you superstitious. When I was writing Orient, I went to that Wiccan store on Ninth Street, and they had these success candles. I thought, “Oh, why not?” So I had one made and started lighting it, but I didn’t really want to fall into some sort of psychological dependency on it. But then I was too scared to stop because I was starting to write well and move ahead. Now I wonder if I should get another one. In fact, we should leave here and go buy candles. I’m serious.

WALLACE: We’ve talked a bit about the ghettoization of murder mysteries in terms of genre, which is lessening, I think. People are starting to embrace them as a viable part of literature. And I think there’s nothing better than a murder mystery. A murder mystery is like a Trojan horse. You can smuggle anything in on that.

BOLLEN: I don’t know why there is such shame in reading them. I have some academic friends, and they mention that they read murder mysteries at night. And they say, “Don’t tell anybody.”

WALLACE: Sartre famously claimed that he would rather read detective novels than Wittgenstein as though he were ashamed of it.

BOLLEN: What is that shame about?

WALLACE: Because it’s enjoyable and we’re puritan?

BOLLEN: They think it’s escapism. But I have to say I do read partly for escapism. Why can’t I escape and learn something?

WALLACE: Well, certainly if the contract the writer has made with the reader is, “I’m going to entertain you or illuminate you …”

BOLLEN: That’s interesting. What is the contract with the reader?

WALLACE: Outside of, say, a stand-up comedian, it is the hardest sell. It is so easy to put down a book. If you are not absolutely goddamned dazzling me, I’m going to stop. It’s the highest bar, I think, which is terrifying. But the stakes are also higher because the pay off, which is the reader’s participation, is also so much greater—their own projections fitting into the grooves of the work … The first time I read Justine, the first book of The Alexandria Quartet, I got 50 pages in and was like, “Wait a minute, I have not been doing this right. I have misjudged you, mistreated you.” And I started over. I wasn’t reading it well enough. And when I went back, every sentence snapped. It bloomed. It has all the Baghdad-ness that Agatha Christie did when I was a kid. It’s exotic. It’s dangerous. There’s a citadel, and Kabbalists. To this day, it’s one of my favorite books.

BOLLEN: What monsters or comic-book figures did you like when you were little?

WALLACE: I didn’t like monsters. I think it’s an aesthetic decision as much as it is anything. I wasn’t a superhero person, and I wasn’t a monster person. In a way, of course, Sherlock Holmes and Poirot are superheroes. I want them to battle evil. But they’re glamorous. I want my superhero to have a mustache comb and drink tisane …

BOLLEN: That’s why James Bond was kind of great.

WALLACE: I still love James Bond. I’m still 8 years old. Which may be why your character Magdalena, the sage activist, is basically my favorite, albeit fictional, human being ever. Have you ever had an amazing leftist lesbian mentor hero?

BOLLEN: No. I’ve never had a mentor. I’ve always wanted one. I’m actually really disappointed that nobody took my under their wing. I think it’s because of AIDS. We lost so many talented artists and writers from the generations before ours that we’re really lacking older figureheads. But in a lot of ways, work was my graduate school. Talking to all those great writers and artists for the magazine was a form of graduate school for me.

WALLACE: So now that I’m completely psychoanalyzing you … You were writing Orient when your dad died?

BOLLEN: That’s right. I was about a year into it.

WALLACE: Did you already have that setup, this drifter kid who is taken in by a father figure?

BOLLEN: It’s like that old Tolstoy line that every novel is either about someone going on a journey or a stranger coming to a new town. And for a zillion reasons, Orient needed the drifter, Mills. There is something very romantic about the orphan figure in American literature. And I think I was also taken with those streams of teenagers who come to the East Village in the summers and sleep on the sidewalks and beg for change. We used to call them gutter punks. But really somewhere between 20 to 40 percent of homeless youth in New York City are gay, or actually LGBTQ; they’ve been kicked out of homes and came where they could. And Mills is a bit feral like that, he is looking for a home, a place to land. He’s been looking for a parent his whole life, in a sense.

WALLACE: What kind of books did your parents read when you were a kid?

BOLLEN: Both my parents were big readers. My dad liked more macho adventure books like Shogun or spy novels. My mother reads murder mysteries. In fact, so does her mother, my grandma. That’s where I trace the familial line of murder mystery obsession. I would stay at my grandma’s house on my birthday every year and I remember she had a bookshelf of murder mystery books along with really frightening books, like one on Jack the Ripper. She also had a poster of a shark in the closet which also terrified me at the time. It was basically a picture of Jaws. I told you I was a frightened child. I remember watching Jaws [1975] for the first time. My sister and I had been sent to some cousins in the country when I was 6 or 7 when my parents went to Europe. It was on in their dark, sunken den, and I remember I was so frightened, I walked up the steps and out of the house and into the cornfield as the sun was setting. That was the beauty of the Midwest. There was no ocean, but there was isolation, that strange, American isolation. I think really the terror of those movies as a kid is the realization that you are also vulnerable, that you are going to die. It’s like that Gerard Manley Hopkins poem, where the little girl Margaret is crying because the flowers are dying. “It is the blight man was born for, / It is Margaret you mourn for.” Margaret is really crying for herself because she realizes she, too, will die one day. Did you watch a lot of horror movies when you were little?

WALLACE: No, I actually don’t like horror movies.

BOLLEN: Well, what do you think about that idea in horror—because it’s always that last girl, right?—that it allows straight men to identify with the female victim? I mean, of course, there’s also something sexual about watching the nubile girl in terror. But you do take on her fear as your own.

WALLACE: I think it’s actually an objective fear; it’s not her fear you feel. The fear is in the air; it’s dissociated fear.

BOLLEN: There’s a great scene in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre [1974] that I’m obsessed with: Sally is being chased by Leatherface with a chainsaw after he slices into her wheelchair-bound brother. And she runs into thorn bushes. And she’s getting tangled up in it because she’s running fast; he’s behind her with a chainsaw so he can move agilely through the thorns. But Sally needs to move slowly in order to get through the bushes—she will get farther faster by going slowly because her hair and clothes won’t get tangled and caught. There’s something really beautiful about understanding that, while someone’s chasing you with a chainsaw, you have to move more slowly in order to get away. I actually think that’s true with writing, as well: you can go slower, you don’t have to rush all the time. There is a value to moving more slowly through a story.

ORIENT IS OUT TODAY, MAY 5, AND AVAILABLE TO PURCHASE VIA AMAZON. THIS THURSDAY, MAY 7, CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN WILL DISCUSS ORIENT WITH WRITER HEIDI JULAVITS AT MCNALLY JACKSON IN NEW YORK.

CHRIS WALLACE IS INTERVIEW’S SENIOR EDITOR.