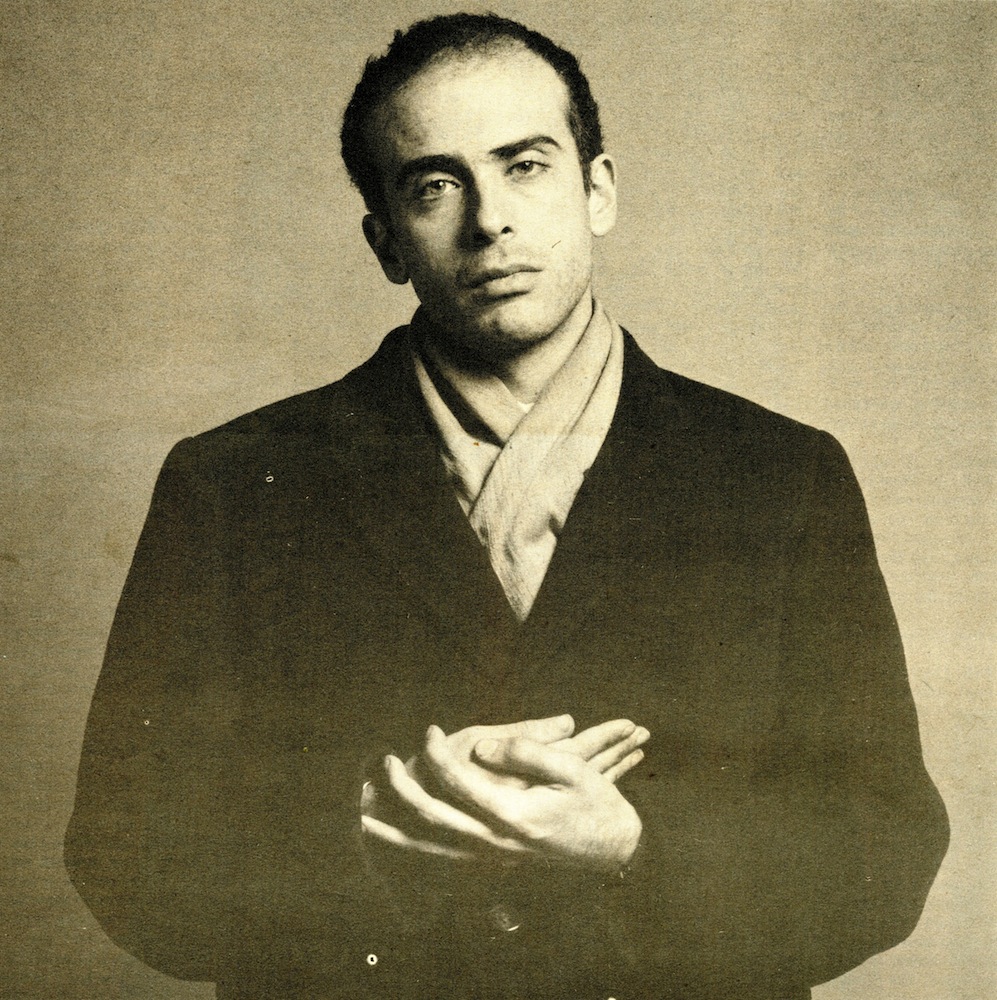

New Again: Francesco Clemente

Neapolitan contemporary artist Francesco Clemente’s oeuvre spans oceans, continents, decades, and media. University-educated in Rome, he split his time between India and New York for the early part of his career, drawing from both Hinduism and Indian craftsmanship and the visual art of Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat. In honor of Clemente’s unique synthesis of these opposing elements over the course of his career, the Rubin Museum of Art—which focuses on Asian art, but has recently presented exhibits with an eye towards fusion of Eastern and Western influences—will offer a multimedia exploration of the artist’s Indian work. This exhibit, the first to exclusively celebrate Clemente’s ties to India, will feature 20 art objects in addition to a series of screenings of films that have inspired Clemente over the course of his career. Clemente will also appear at the museum for eight gallery talks with luminaries of other fields, including director Alfonso Cuarón, musicians Patti Smith and Nas, dramatist Robert Lepage, and chef Eric Ripert. For an added dose of excitement, Clemente has asked each guest to bring a found object with them to spark the conversation. The exhibit, entitled “Francesco Clemente: Inspired by India,” will run from September 5 through February 2.

In April 1982, Interview celebrated another first for Clemente—his first American exposition in 1980 at Sperone Westwater Fischer—with a lengthy discussion between the artist and art journalist Edit deAk, just in time for Clemente’s traveling show throughout the American northeast. The conversation is eclectic: Topics range from the nature of the dilettante to painting as an endurance sport. It’s punctuated by strange outbursts, the occasional interloper, Tarot readings, and a striking scene in which deAk corners Clemente’s model, Veronica, to question her about her impressions of the artist.—Katherine Cusumano

Francesco Clemente: One of the Italian Big Three

By Edit deAk, redacted by Lisa Liebmann

Francesco Clemente draws, paints, uses pastels and makes mosaics and frescoes ranging from the highly evolved style of traditional Italian painting to a naïve and seemingly simple, yet strongly expressive manner of drawing. His intriguing imagery (images being his central focus) is frightening, erotic, sometimes grotesque and usually ambiguous; his work is allegorical in nature and concerned with the myth and reality of being a gifted visionary, an artist. His work is mostly self-referential, about the process of creativity—especially the anxieties.

Born in Naples in 1952, Clemente has been showing his work in Europe for 10 years. He only had his first show in New York, in 1980, at Sperone Westwater Fischer, perhaps owing to this country’s self-possessiveness during the 1970s, or the preoccupation with reductive and process-oriented work. Gaining popularity quickly in America, Clemente has a current solo exhibition at the Wadswroth Atheneum in Hartford that traveled from the University Art Museum in Berkeley, and will have a show at Sperone Westwater Fischer in the fall. His last show in Europe was at the Galerie Bruno Bischofberger in Zurich late in 1981.

EDIT DEAK: Tell me, what do you think of the idea of the dilettante?

FRANCESCO CLEMENTE: I first think of intelligence. You need it for surviving in Italy because Italy is so pompous.

DEAK: So you’re saying it’s posing, it’s a posture.

CLEMENTE: Yeah, because to simply survive, you have to not show yourself. If you want to compete in Italy, the only accepted ways are brute force, or cunning. Like Machiavelli says, “Fronte otra forze.” And neither of these two “virtues” is suited to an artist. The artist has to stay intelligent.

DEAK: So the dilettante’s the self-appointed fool. Dilettantism is arrogance with manners, arrogance tamed in the backward process to humility. By definition then, any artist is a dilettante, in Europe anyway. But in this country there is this other idea that is the total opposite of the dilettante, and it has to do with the “instant image.” What you do is who you are, and you just pick a skill and do it well to project a quick bold-outline character-profile, because that’s all people have time for. Surface is the most confusing tissue around life; it’s supposed to contain everything and everything is supposed to work off of it.

CLEMENTE: And dilettantism is a humorous way to survive amidst all these very complicated codes. Everybody understands you for it and everybody hates you for it. And not everybody chooses to be a dilettante. Many choose cunning and brute force.

DEAK: Do you find many people here like that?

CLEMENTE: Here, and also in India, I find there are totally different reference systems, and the reality is naked. In India and in New York the economy is naked. People are starving physically in India, and emotionally in New York. But here you find your own rough river to swim in. You don’t take the space of anyone else, you take your own place by the side of this naked machine. Here it’s enough just to be a good swimmer in your rough river; it’s a more personal code of survival. In Europe, it’s more a matter of conventions.

DEAK: Here there is a physical space, and in Europe there is only cultural space left, so it has to be a matter of abstract convention. All the space is used up and you can only be a layer on top, not a whole new space. It’s an abstract con game of existence. Another question I have for you, Francesco, is how do you keep such a positive attitude?

CLEMENTE: I was born in a warm, old, Greek city. That’s the funny answer. The pretentious answer is… I don’t want to say. So we’ll stick to old Greece. I mean, you can’t ask this of anyone, because every day it will or it will not happen again, and nobody knows if it’s going to happen again tomorrow. We are not naturally intelligent, or happy. In fact, every day it is harder to remain intelligent. It seems often that people get intelligent through pain, but you can’t be sure because nobody really can say, “I’ve been suffering.” That would be really pretentious. But some people are quite funny about it. When I was in Capri last summer I brought a friend to the Villa Ferca. The villa is turn of the century pseudo this and that, and its motto is “Amori e Dolri Sacrum” —consecrated to love and pain. And my friend turned and said “Love, okay, but why pain?” That’s why I say I’m from Greece. It’s very natural for an ancient Greek to say something like that.

DEAK: To me, the Greek way of taking life, sensation, endurance, is a matter of internal proportion. It has to do with geometry within boundaries. Here, and in the East, I think it’s a matter of addition, of building and building, and putting on more and more shapes, more and more stories, and when it feels right they stop, or maybe they don’t. It’s eyeball methodology, which makes a completely different harmony. I don’t know. It’s been so chic to be agonized in the West.

CLEMENTE: Agony is also what makes the dilettante in Italy, no? It is a form of detachment you get, you know, that can be useful for a screen—screen that is useful for a screen.

[Edit and Francesco read Tarot cards in Francesco’s studio, surrounded by the 12 immense oil paintings Francesco has completed during his last two months in New York.]

CLEMENTE: Sometimes the cards like to repeat themselves, like variations on a theme. The way to read them is almost like reading music. Again this set of cards talks about limits. The Pope has to do with boundaries, order that you cannot defeat or defy. It has to do with bondage, but not in a negative sense.

DEAK: Like tradition?

CLEMENTE: Well, the Pope is centered among four elements, which is like the old image of the cross, the cardinal points. North is delusion, South is pleasure, West is fear, and East is for hope. These are the extreme limits of what one is able to do, the activity and possibility of man.

DEAK: So is India hope for you, and New York fear?

CLEMENTE: Well, California is fear and New York hope. And downtown is pleasure and uptown is delusion. It is always good to read the cards as though moving between external, accidental phenomena, and internal repetitive phenomena. Whenever I find cards that represent people, I like to think of the internal meanings. I don’t like to look at someone as being fixed. When we talk about forces, I understand. When these things become anthropomorphic, I feel uneasy. It is very scary to think mechanically about someone you know. That means that the second time you meet a person is useless. Which I tend to believe anyway.

DEAK: There’s the Moon. The Moon is hysteria, anxiety, the noise of life?

CLEMENTE: The Moon is like it has happened a thousand times over. For instance, I repeatedly refuse to make any practical decisions. I get a feeling of nausea about practicality. The Moon is like when your spirit…

[Long silence. Edit and Francesco study the 12 giant oil paintings on the walls of his studio.]

DEAK: Do you realize that gradually you have painted all the water out of your paintings? The first four were basically all water, almost 90 percent.

CLEMENTE: Yes, well, in any work you do it goes like breathing, in and out, accumulating and spending. So years ago in Italy, the accumulation for me was not exactly like water, but a continuous flow, like a flood of drawings. One line going and going and going, so much that I was practically buildings dams—frames, conventional frames to stop this flood of images. The moment the images were framed, they started to flower, to grow, and to show themselves in an almost pleasant way. A few months ago, I was looking for the black of the ink, for the really black, flowing clarity of thought. In fact I couldn’t draw, and I felt I was entering the second half of my life and I wanted to be a painter. So I came to New York to be near where the painters are, to be where the great painters have been. Another sort of frame is to work in harmony with your environment. In India, for instance, the market is so far away, and it is so hot. You go, and it proves to be empty of anything you actually need. Once, at the market in India, I saw a man holding in each hand an old 78 LP, carved with figures of peacocks and gods, things like that.

DEAK: On the vinyl itself?

CLEMENTE: Yeah, like they carve ivory. But if you are not really in the market for carved records—if what you want and really need are crayons and paint—the carved records are not very likely to fill the gap. So what did I do but stay in the garden, digging up the earth, which happened to have four different colors. All in the same garden, all different. So I draw with these colors. And the paper looks like it will fall apart, but it doesn’t. It’s handmade, it’s real paper, it lasts. These works all look like they’re crumbling—but wearing the best suit all wrinkled, now that’s style! Anyway, in Italy, I only wanted to paint with the line, and I made mosaics and frescoes.

DEAK: So, when you came to New York, you had to paint your way into the city.

CLEMENTE: Yeah, I wanted to get something new going, and to do that I needed to do something that I didn’t know, and that was to paint large oil paintings. I added the light, the light of the night, which I know very well from the paintings I lived with when I was a little boy in Naples—1600s stuff like Luca Giordano. To me, the paintings I made here look as if they were made in a dark church in Naples, but to a friend in Italy, they look as if they were made in the winter light of New York. In Italy I have this big, literally, this mountain of drawings. So now I’m in New York and these 12 paintings are the root. When I am in India, I don’t need paintings, because there is the monsoon, and everything is washed away.

DEAK: But what motivates you? What do you have to do with the monsoon?

CLEMENTE: I can’t say the truth.

DEAK: I hope not! I think the painting must have been tough for you because of all these years of complete facility and mastery of this diarrhea of lines, and drawings, and the pleasure of seeing images surface instantly.

CLEMENTE: The only thing that made a difference in painting was that I’m not fat. In India, drawings were perfect for me because I was used to my body having a lot of rest. To paint, I have had to really fight to get ready. Now the images come with facility, but to get the ground of the painting ready you really need unnatural body strength. It’s the kind of strength that Indians draw on when they take certain drugs and dance for three nights straight. To make paintings is a little like that. It’s exercise. You need strength. You need to be an athlete.

DEAK: You manage to work, to do your art world shift by day, and you are practically the only rising-star painter who actually hangs out at night.

CLEMENTE: Yeah, well, I am a tourist, you know.

DEAK: I am the tourist. You are the artist, this is the artist’s studio, those are the paintings, this is the artist’s wife in a Chanel towel, this is the artist’s child, that is the punk babysitter on drugs. No, really, it’s incredible. Your studio has evolved into this giant open-house of the libido. I can’t believe the absolute natural flow of internal life in this house: the sound, the bird, the kids —just the rhythm. You have the only place I know, Francesco, where I don’t miss music. Usually I feel sorry for people who don’t blast it all the time, and sorry for myself for having to cut through an entrance without the softening of background sounds. In Rome, your house is practically inside the foliage of the botanical gardens in Trastevere. And here you’ve painted a lulling foliage so naturally connected with New York, that I don’t even miss music. You should market this perpetual-life soundtrack to one of the special-effects recording houses. But all these undercurrent rhythms, how do you handle it? All these models, and girls, and light-night comings and goings—is it perhaps to get it out of your system after all those years you stayed in to masturbate?

[Edit corners Veronica, Francesco’s model, in Francesco’s bathroom. Veronica is also a baker. She makes erotic cookies —penises, breasts, animals, tiny sculptures she whips up in seconds.]

DEAK: Tell me about the first time you walked in here.

VERONICA: [with some trepidation] Okay. I walked here from First Street. Francesco opens the door. He looks friendly enough, like an okay guy. He looks like a regular guy. I wouldn’t pose for anyone if they were anything less than an artist. Anyway, I came in the long hall, and there were the paintings, and there were a good many of them.

DEAK: First impression please.

VERONICA: I said that there were a lot of dangerous things going on in the paintings. I said this man is really playing with fire, he is really taking chances.

DEAK: Did you think they were sexy? Or if there was some giant erotic cave, or suction of turpentine libido?

VERONICA: Oh, wow. I guess I felt that subliminally. It is strongly enveloping. I felt very comfortable. I knew I could take my clothes off.

DEAK: There is also a certain sexiness in the touch, or in the motifs, but I guess this abundance of sex is the very topic itself. While you can be a great painter, that doesn’t necessarily mean the work is sexy. But his is. If he paints a toothbrush, it’s sexy.

VERONICA: Aha.

DEAK: If it’s sexy, you don’t have to make it sexy, it just is. His household is sexy, don’t you think?

VERONICA: Yeah. He is always surrounded by women.

DEAK: There are nine women here now. I counted them.

VERONICA: [laughs] You did?

DEAK: Yeah, I actually did. I am a girl reporter on the make. But how do you get a handle on it? Is it the rhythm of the way they live?

VERONICA: Well, I would say that he is a man whose needs are taken care of. He is a man supported by a family and who is producing prodigiously, magnificently… I felt that what he was doing was really true. I knew myself. I know that I don’t have a big red streak going down my forehead, or ochre under my nose. That’s it! It is a respect for him. To me that is greater than being in a movie… You look in the mirror in the morning and you see how you look. That’s the operative face. When I saw him paint my face in three different ways, I felt beautiful, complimented in such a fabulous way. It was so much more than being on a movie screen or being in photos, just pretty, or capable, you know.

ALBA CLEMENTE: [entering] Edit, there you are. I’ve been looking for you.

DEAK: Oh, well, nothing like hanging out with Francesco’s model in his very own bathroom.

FRANCESCO CLEMENTE: [entering] “To me toilets are like the church to Catholics. Whenever I see one I have to go in.”—Proust.

THIS ARTICLE INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE APRIL 1982 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.