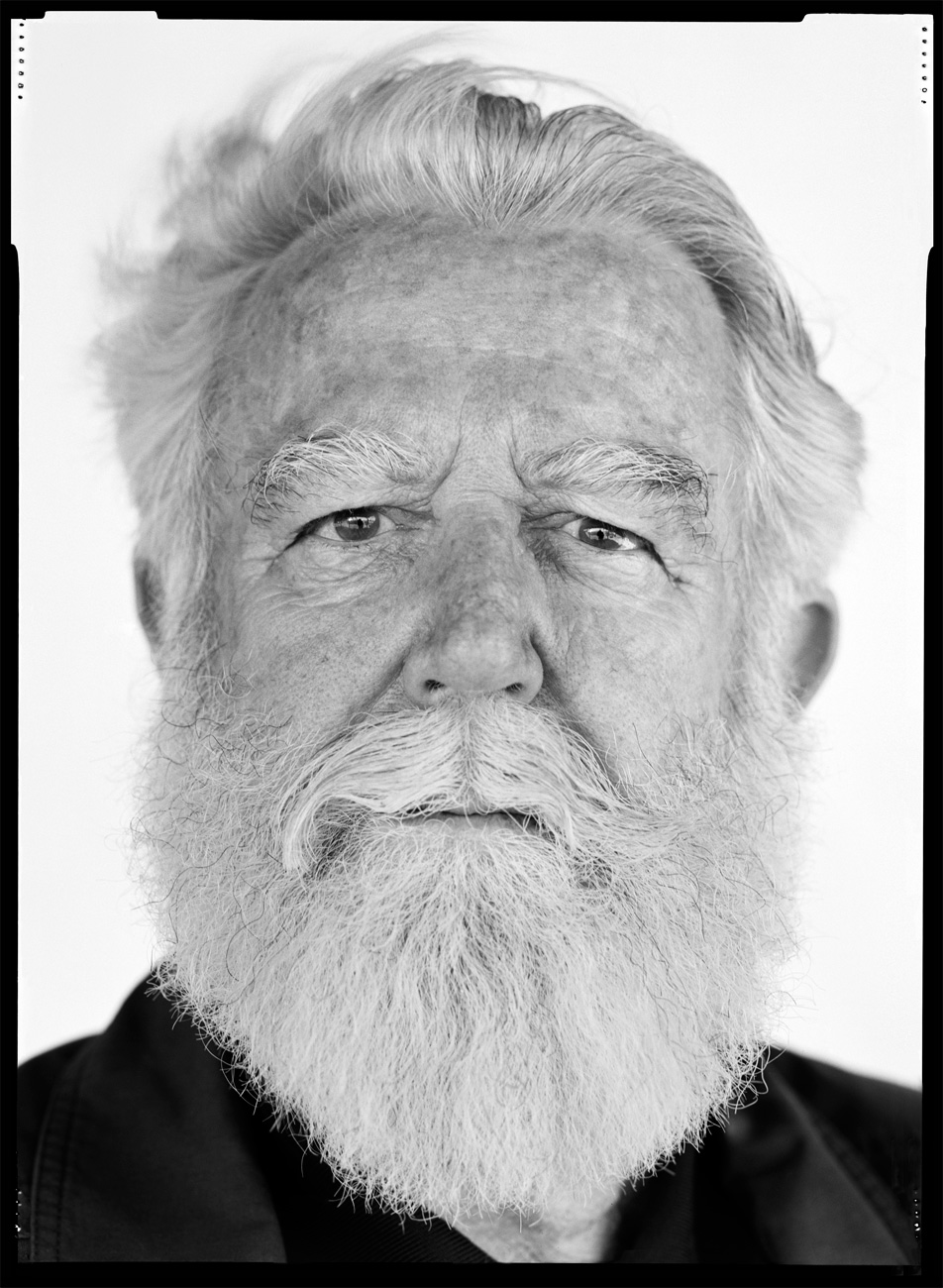

James Turrell

I’ve always felt that night doesn’t fall. Night rises. There are these incidences in flying where you just sit there. It’s one of the best seats in the house.James Turrell

In the 1960s, by manipulating light rather than paint or sculptural material, James Turrell introduced an art that was not an object but an experience in perception. It examined the very nature of seeing. Over the next half century, Turrell has become known not only for his light projections and installations but especially for his continued work for more than three decades on his Roden Crater project—the conversion of a natural volcanic crater on the edge of the Painted Desert in northern Arizona into one of the most ambitious artworks ever envisioned by a single artist.

A pilot and rancher, and conversant not only in art, but equally in science, literature, history, and religion, the 68-year-old Turrell is one of the most multifaceted artists of our time. Having known his work since my own art studies in the 1970s and ’80s, I first met him when I became director of the Dia Art Foundation in 1994. Dia had been instrumental in helping Turrell begin work on Roden Crater but the organization soon abandoned the project for lack of funds. My intention was to rekindle Dia’s support for that artwork, which seemed to epitomize Dia’s founding focus on singular epic-scale artistic vision. Roden Crater is still under construction today, and I now maintain a support role from the vantage point of Los Angeles, where Turrell’s ideas and art first emerged. In fact, one could argue that Turrell’s upbringing in Southern California, as well as his religious rearing as a Quaker, play a large role in his work. But to limit the works to biography is to risk missing their purity and emotional resonance.

Currently, I am co-curating a retrospective exhibition on Turrell, which will be on view at my own Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 2013, as well as at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. In the meantime, the prolific artist is appearing in a number of shows—including an installation at this summer’s Venice Biennale, and his first solo exhibition in Russia at the Garage Center for Contemporary Culture in Moscow.

Turrell helped nurture my own interest in aviation. This past May, after work on a clear evening in Southern California, I flew my own tiny airplane to Flagstaff and talked with Turrell at a famous Route 66 establishment, the Little America truck stop and hotel, not far from his nonstop work-in-progress, Roden Crater.

MICHAEL GOVAN: Everyone has trouble describing your work in words, because it is wordless work. Often, it’s been spoken about—and you’ve spoken about it—as making light palpable. But the more time I spend with the work, the more I really do feel that it’s about seeing.

JAMES TURRELL: It’s about perception. For me, it’s using light as a material to influence or affect the medium of perception. I feel that I want to use light as this wonderful and magic elixir that we drink as Vitamin D through the skin—and I mean, we are literally light-eaters—to then affect the way that we see. We live within this reality we create, and we’re quite unaware of how we create the reality. So the work is often a general koan into how we go about forming this world in which we live, in particular with seeing.

THE TRUTH IS THAT PEOPLE WHO LOVE THE DESERT ARE CRAZY. EITHER THE DESERT ATTRACTS PEOPLE WHO ARE CRAZY, OR AFTER THEY STAY IN THE DESERT FOR LONG ENOUGH THEY BECOME SO.JAMES TURRELL

GOVAN: That’s one of the things that I always come away with. We often forget we are making all of this—all that we see in the world and in your work. Your work is very viewer-centered.

Turrell: Yes, otherwise it doesn’t really exist.

GOVAN: You studied psychology when you were in college in the 1960s at Pomona College in Los Angeles.

TURRELL: The psychology of perception.

GOVAN: When did it make sense to bring that psychology of perception into art?

TURRELL: I had an interest in art through several friends, [artist] Mark Wilson and Richard White, both of whom went to Yale [University School of Art]. I was hoping to get into Cooper Union [for the Advancement of Science and Art] at the time but was not accepted. So they were very influential, along with the teachers [at Pomona College], Maury Cope and, in

particular, Jim Demetrion. Demetrion was very interested in getting males involved in thinking about art, and he sort of attracted males to art classes because he thought that’s where the best females were. This he totally denies. That denial is perhaps even true, but at least that’s what we all thought at that time. [laughs]. And it was true because some of the nicest-looking and most interesting females were in these art classes. So we went there, and what we all thought would be an easy grade turned out to be quite tough. We were sort of seduced into this, and then we actually had to perform and learn the stuff.

GOVAN: Was that the moment it clicked for you?

TURRELL: Again, I had an interest in art, but my first interest was actually in light. I was always fascinated by light. Just like there are children who love fire, so they want to be firemen. If you love light, what do you do with it? One thing is that the history of light is littered with paintings about light. Like the great light school in Holland. And you have Constable and Turner, not to mention all the impressionists. Then there’s the more emotional, southern view of light, where you have Caravaggio, Velázquez, and Goya. I bought Goya’s Caprichos when I sold my boat. I had built a large boat that I didn’t complete, and I sold it and bought those, and that actually sponsored my beginnings in art. I made a little money on owning those prints. That affected my making Emblemata [a limited-edition black-and-white artist’s book on light forms, 2000], and in particular the First Light [a series of aquatint prints whose subject is the first body of light works, the Projection series (begun in 1967), which reproduce the bright form of light as it contacts the wall plane, 1989-90], and, even more so, Still Light [a series of aquatint prints that continue the examination of the effect of light projections by revealing the quality of light released into the space of a room, 1990-91]. So this interest in light became fused with the psychology of perception. If you take blue paint and yellow paint and you mix them, you get green paint. But if you take blue light and yellow light and mix them, you get white light. This is a shock to most people. But I was interested in math as well. Euclidian geometry is wonderful, but you can’t hit the Moon with Euclidian geometry. You have to use Riemannian geometry where in space the curved line is the closest between two points. You realize that you have to go to this next level if you’re going to talk about seeing. You have to talk about light, and not just light reflected off the surface, which has to do with painting. Rather than making something about light, I wanted something that was light, and that’s the biggest difference.

GOVAN: By doing that in the field of art, you just take the middle man out of it, right? You take away the paint and the sculpture, and for you, it’s simply directness.

TURRELL: Yes. [Art critic] Nancy Marmer wrote a very good piece about this idea to get rid of the object, and it had to do also with a political statement about value and worth and things like that. The truth is, I wanted people to treasure light as we treasure gold, silver, and, of course, paintings. And I’ve used light to construct an architecture of space—in the sense that if you think of how we look at night and day, when daylight’s the atmosphere, we can’t see through it to see the stars that are there. So generally, we use light to illuminate or to reveal, but light also obscures. I look at light as a material. It is physical. It is photons. Yes, it exhibits wave behavior, but it is a thing. And I’ve always wanted to accord to light its thing-ness. That was very important to me to do.

GOVAN: Is it fair to say that this interest in light had something to do with growing up in Los Angeles? I make the analogy sometimes that if you look at European paintings, you can see a difference in the work painted in Venice by Tintoretto, Titian, and Veronese, and their obsession with light. You can’t help but connect that to the omnipresent light in Venice as it’s reflected on the water.

TURRELL: Yes, but at the same time, you have Turner and Vermeer. They were in places where really amazing displays of light were rare, and so they treasured that. It can work both ways. In general, in the societies in Europe, it more often happened where light was rare. And then, when they got successful, of course, they went to the South of France. [laughs]

GOVAN: So they could have it every day—which is like Los Angeles.

TURRELL: Yes. This is what happened with L.A. [laughs] But you have to remember, when I came into L.A., L.A. was really exciting as this place that was involved in [outer] space. The rockets were shot off from Cape Canaveral [Florida] and they were controlled in Houston from the Lyndon Johnson Space Center. But almost everything was made in Southern California. That optimism of the space race and of aviation and of this venture into the skies really happened in L.A. And it was a time of tremendous optimism. [Artist] Bob Irwin and I worked on the Spacelab with Ed Wortz. [In 1968 and 1969, Turrell and Irwin worked on the Art and Technology program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art with Ed Wortz, a scientist at a Southern California aerospace firm called Garrett Corporation]. We did this, and we were involved in the training of astronauts. This was quite a heady time.

GOVAN: So L.A. was an environment not just because of its physical quality of light, but because of that obsession of the aerospace industry with space and light.

TURRELL: Yes. And my father had some involvement with that kind of work too [Turrell’s father was an aeronautical engineer and educator], although not when I was alive. So I had some of that in my family. It was absorbed almost as revisionist history from my father’s library, which I did inherit.

GOVAN: Your father’s library was a library of aviation and space. That was a huge influence in itself. I like that we can reverse “light and space” as your art is sometimes referred to, to be about “space and light,” because now we are talking about space as something other than just physical space—it’s outer space.

TURRELL: There is the idea of how you make space within space, or this architecture of space created with light. You see that when you fly. Sometimes you’ll see a contrail, and a shadow comes down and it makes this division all the way from that contrail down to the earth. You see that plane of the shadow. That’s where I got into things like doing those planes like in the Wedgework series [rooms that have been constructed so that light falls in a way that divides the space along diagonal planes], or in particular in Virga [a site-specific work from Veils, which are variations on spatial division by means of artificial light, 1974]—those are directly out of that. It is sometimes difficult to do these things on a small scale. It objectifies too much if it’s too small. I like the quality where it seems like it’s ephemeral, but then it makes a solidity. That requires space. Now, we had cheap space for studios in L.A. back then. I rented a whole building [the former Mendota Hotel] for $125 a month. That seemed like a lot at that time . . .

GOVAN: The building in Santa Monica. It’s now a Starbucks.

TURRELL: How this happens to artists . . . it’s just embarrassing. My great studio is now a Starbucks. [laughs] We had cheap space. Those were works that luxuriated in space. The difficulty was to take the work to the East Coast. I remember going to see Castelli’s gallery in New York. And again the problem with space happened in Europe, because all the galleries were very small. So that was difficult for pieces that needed some distance. For me, with distance, you could have it looking very solid, and then, as you approached it, it began to dissolve, so you could get this quality of being both ephemeral and physical. Now, of course, the space to do it is in the sky. One of the biggest examples of this light-making space is the change from night to day or day to night. But this idea of movement, your passage as you approach something, and this change in your feeling of space, plumbing it with the eyes, this whole idea of visual penetration, is very important. I worked at it in Skyspaces [structures featuring an opening in the ceiling (usually circular or rectangular) that deal with the juncture of interior space and outside space by bringing the sky down to the plane of the ceiling]. You can have a space that’s absolutely opaque as you get toward the night, where it’s ink-black or blue-ink-black, or even a little bit before that, and it looks like it’s been painted on the ceiling . . . It becomes quite impenetrable with vision. But there are other times I like this transparency, too, where you go from transparency to translucence to opaqueness. And that quality of plumbing a space with vision was very important to me in the poetry of the work.

GOVAN: Of course, one of the most beautiful moments of Roden Crater is when, after climbing the main tunnel at night, walking toward a dark circle, you allow the viewer to literally pierce that circular black veil by going up a staircase, and walking through that seemingly solid black ceiling into the night sky as the stars and planets begin to appear for you.

TURRELL: Yes, on a moonless night, because it is just absolutely black, and then you go up the staircase, and it’s like going in front of the footlights of a theater stage. What was flat and black starts to dome up again, and really dome, into this beautiful universe. So this connection, or journey in a small, short space is the kind of thing I always wanted to do. That’s just the architecture of light into space. Then, of course, I have had to use architecture because . . . Well, like at P.S. 1, and CoCA, and the Mattress Factory, and [at Le Confort Moderne] in Poitiers, France, I could actually take somebody’s building, cut the top of the roof off, put a 35-by-35-foot pool in it. . . But I think architects get a little bit sensitive about those issues if they made the building. So actually what I had to do was then begin to make the building with a hole in it.

GOVAN: All the way from the early days, where you were scratching openings for light on windows you had painted black in your Santa Monica studio, you’ve now virtually become an architect. You make all that architecture to hold light, right?

TURRELL: I like to say that my work is an architecture of light into space. But on the other hand, I had to move a lot of material. Even at Roden Crater, just to get this celestial vaulting to happen above you, we moved 1.2 million cubic yards of earth. So I do get involved in material. You have to make the space, you have to enclose it. I sort of make these enclosures to capture or to apprehend light for our perception. So they’re kind of these vessels or places that allow it to gather for you.

GOVAN: There’s a long tradition of that in architecture. You are engaged in a dialogue with a certain side of architecture that deals with open light and shadow.

TURRELL: Yes, that’s absolutely the case. And I don’t deny also a great joy of architecture. I think that these enclosures that we inhabit have to do with the reality we form. I mean, we’re a lot like the hermit crab. We’re in this enclosure here. We go outside and get into a movable shell and zip off to another place, and get out inside of another one. So it’s kind of musical chairs with these shells—the shell game—and these things that enclose us. We often enclose ourselves in ways that don’t let in the outside very easily. So I like to cut through and open these things up.

GOVAN: In your recent work, I think about how you’ve investigated that outer shell and its relationship to the natural environment. You’ve buried spaces partly underground as at Roden Crater. You’ve put natural stone around them, as in the literal pyramid you’re now building in Mexico. When you use materials, for example, like bronze, you’ve used a bronze that holds light. It’s amazing to me.

TURRELL: That’s a place where other artists have gone before. The interesting thing about my early work and Bob Irwin’s early work is that he would often take a material, like his Plexiglas disk, or a scrim, and he would dematerialize those into the light aspect. I would often take just light and sort of materialize it into a glass-seeming surface of volume. So we sort of came at similar things from opposite ends. In this more recent work that I’ve been doing, I owe a lot to all those artists who have been dealing with glasses, particularly the Japanese. Screens and glasses and scrims are something the Japanese have done amazingly. I’ve tried to incorporate that, and even incorporate some of the forms of different cultures, whether it’s the stupa form [an ancient dome- or bell-shaped Buddhist shrine], or our own ideas of UFOs. If you look at the time of [science-fiction action hero] Buck Rodgers, all the UFOs had rivets. So it’s been getting very interesting in how, as our culture progresses, the UFOs that come to visit us are also getting more advanced. I think that has to do with how we deal with UFOs or psychic phenomena or even religion in our culture. I’ve been fascinated with that as well, because I came out of a very strict religious upbringing, and I’m still involved with it.

GOVAN: Well, you came strongly back to Quakerism. Not that your Quaker upbringing was lost, but when you did the Quaker [Live Oak Friends] Meeting in Houston [a contemporary building that takes Quaker history as well as contemporary and environmental needs into account, featuring a Skyspace made possible by a retractable roof in the center, constructed from 1995 to 1999 and opened in 2001], your Quaker upbringing is deeply evident.

TURRELL: I got pulled back in, yes. Well, even a little bit before that, because the astronomers here in Arizona were Quakers. In fact, the clerk of this Meeting in Flagstaff was Richard Walker, the astronomer that worked with me on the Roden Crater project. So I did get pulled back in. Richard and I had similar experiences during the Vietnam period. I had to deal mostly with my self-righteousness, which Quakers have to deal with as well—and liberals, too. [laughs] But we don’t need to talk about that.

GOVAN: Yeah, it’s interesting how the Quakerism has come through your life in so many different ways. The Skyspaces are Meetings.

TURRELL: Yes, they are Meetings. The first one was named Meeting [a site-specific installation at P.S. 1, which consists of a square room with a rectangular opening cut directly into the ceiling, 1986]. I sat in it, and I realized I’m making the Meeting I always wanted to see. Because when I was a kid, I used to think about this idea of a convertible. Remember the ’57 Ford, which actually retracted a metal roof back into the trunk? That’s a little bit wild for a Quaker kid sitting there in Meeting, thinking about how a roof comes off. . . . But thoughts go everywhere when you start to meditate. The first five or ten minutes of meditation always has these rather fertile thoughts. It’s an exciting time, just like when you awaken. I think that one of the most amazing things is awakening from a dream. The dream is leaving you as you awaken. It’s just like the New Year’s resolution. You’re really hot on the New Year’s resolution. You go and join a sports club or something like that. You work out, and four months into the year, you’re wondering “where was that?” The same thing happens every day when you wake up. We start with this resolve, and it’s hard to take it from this other land, this other area. I’ve always wanted to make a light that looks like the light you see in your dream. Because the way that light infuses the dream, the way the atmosphere is colored, the way light rains off people with auras and things like that . . . We don’t normally see light like that. But we all know it. So this is not unfamiliar territory—or not unfamiliar light. I like to have this kind of light that reminds us of this other place we know.

GOVAN: There is a deep sense of light at the heart of Quakerism. I know that from my own high school education at a Quaker school.

TURRELL: Quakers are called “the children of light.” That was originally their title.

GOVAN: And you talk about the idea that Quakers find the light inside.

TURRELL: Yes, you go inside to greet the light. That’s what my grandmother always used to say. Quakers also don’t use words like “Sunday” or “July”—these were pagan names, so they would never use those words. You go to the first day of school, and it’s firstmonth, first day . . . They’re crazy people.

GOVAN: You people.

TURRELL: Well, yes, I have to say that. I have to admit that.

GOVAN: But greeting the light. You do that in a meeting?

TURRELL: In your meditations in the meeting, yes. That’s what you’re meeting.

GOVAN: Which is so close to a certain amount of your work.

TURRELL: I suppose so. I am claimed by these people, as Bonnie Raitt and James Dean and Joan Baez were all Quakers.

GOVAN: Let’s talk a little about flying. When we’re together we always spend as much time talking about flying as we do about art.

TURRELL: Do we spend as much time talking about art as we do flying? That’s a better phrasing of that question.

GOVAN: Obviously, we share a love of flying. You’re partly responsible for my first flying lessons in that you wouldn’t take no for an answer when I said I didn’t have time to fly. Now I’ve been flying for 16 years, and I just got a tiny 1960s airplane for my daughter to learn to fly.

TURRELL: I have nothing to do with your fleet purchases.

GOVAN: Let’s say it’s more than a passing interest for both of us.

TURRELL: That’s right. You can’t do it with one plane. We know that. I apparently have not been able to do it with eleven planes.

GOVAN: Which will become your museum of airplanes some day?

TURRELL: Each child has to have a glider and a short-takeoff-and-landing airplane. And then they have to have a plane that they can fly with their mate and a child and luggage, then one that’s aerobatic. Maybe one that lands in the water . . .

GOVAN: You once said your airplane was your studio.

TURRELL: Yes. We were talking about this line that came down from the contrail. Also what happens flying toward a sunrise or a sunset or the other way, when you see the earth’s shadow rise opposite the sunset. I’ve always felt that night doesn’t fall; night rises. There are these incidences in flying where you just sit there. It’s one of the best seats in the house.

GOVAN: It’s interesting if you think about early 20th-century art, and the influence of the airplane on Russian Constructivism. Everything is looking down at the ground for an aerial perspective of form and geometry. But you take the airplane and look the other way into the sky.

TURRELL: For me, the thing with the Ganzfeld pieces [works in which the space or room is completely filled with homogeneous light and free of objects] in particular, I’m interested in this new landscape, which is without horizon. This landscape without horizon is very much like IFR flight [instrumental flight rules that govern civic aviation], which you don’t enter naively. I’ve also had to deal with people who’ve fallen in one of my works because they feel disequilibria . . .

GOVAN: I see. In the Ganzfeld works, the viewer enters a space of pure light with no discernible depth or direction. Early pilots fell out of the sky when they were in the clouds before they had instruments to tell them which way was up.

TURRELL: Yes. Also, in terms of disequilibria, it has more to do with vision than with the inner ear.

GOVAN: It’s the brain being confused by vision.

TURRELL: This world that we inhabit has a lot to do with the reality we form through vision. So I am very interested in how we create this world that we inhabit, and general koans nudging us into this newer landscape, the landscape without horizon, without left or right, up or down. . . . I mean, if you take images of my work, they are often printed backwards or upside-down. But it’s okay. They’re the same, what difference does it make? I’ve always been interested in celestial vaulting. I’ve been interested with taking out the horizon. So it is a new landscape, this new place that we are headed, and it’s a little like cyberspace. But on this idea of flight, one of the most interesting things about the challenge of flight and the plan view of the earth as opposed to the maze of being on the ground, is that one of the first things that happens is you can see 100 miles and you can’t find the damn airport. Because you just don’t know how to think in plan view. It’s taking your thinking to this other level. This happens in flight, and this is what art does. Art does take us to this next level, whether it’s aesthetics, or whether it’s even about common objects, or whether it’s about the art of advertising and the things that are around us all the time. It takes us and broadens our perspective. One of the biggest disconnects in art is people going to an art exhibition to find things they like. I can tell you that’s the furthest thing from any artist’s thinking that you can imagine. They couldn’t give a shit about what you like. If anything, they would like to change what you like. So this disconnect between how people buy work and how the art is supported, and what the artists are doing, is huge. But it’s something we all have to deal with, and nonetheless, there we are. That has to do with our humanness. But getting back to aviation, it’s the same as diving or the submarine is into the depths. There is this rapture of the deep. There also is this rapture of the heights. Often, it comes with oxygen deprivation. Because we are taking our old selves into the new realm, and so we have to do it with these devices, these things, these—

GOVAN: Machines. Shells.

TURRELL: Shells, yes. And these shells are part of us. People think of being attacked by technology, when technology is us. So the fact is that these shells that we use are no different than the shell that the hermit crab has. They keep adopting a different one as they get larger, and so they kind of race to new ones. As we rebuild these houses, and small houses that were needed before now become mega-mansions, and so on and so forth. But this is us. You can’t take the little creature that makes the coral reef and separate that from the Great Barrier Reef, which is the first thing made by any living creature that could be seen from space. They had about as much knowledge of planning and zoning as we do when we made our cities. They get change, and there’s corruption, and then they change the rules, and then there are new developers and they want new rules.

GOVAN: We both have a lot of respect for the Russian Constructivists. Malevich, before them, was about seeing in a pure way, underneath the politics of revolution, even underneath the way a society is constructed. He was after what he called “a desert of pure feeling.”

TURRELL: Yes. A desert of pure feeling. And I have literally brought that into the desert. The truth is that people who love the desert are crazy. Either the desert attracts people who are crazy, or after they stay in the desert for long enough, they become so. It’s no different with art. I’m not so sure which comes first. But after being in it long enough, what difference does it make?

GOVAN: There’s a sense of emptiness, of clearing everything out that you’ve had here at Roden Crater in this high desert. Roden Crater is probably the grandest thought that a single artist has had.

TURRELL: Yes, but no more profound than a haiku written on a shopping bag.

One of the biggest disconnects in art is people going to an art exhibition to find things that they like. I can tell you that’s the furthest thing from any artist’s thinking that you can imagine. They couldn’t give a shit about what you like. If anything, they would like to change what you like.James Turrell

GOVAN: People don’t understand the idea of Roden Crater’s monumentality. The more time I spend at Roden Crater, the more intimate the experience is. Its largeness really comes from the existing landscape, the existing physical, environmental landscape.

TURRELL: It’s not a very big volcano; it’s modest.

GOVAN: By volcanic standards, it’s small. It’s about half as high as the Chrysler Building and a few miles wide.

TURRELL: And the bottom is about as wide as Manhattan, that’s true.

GOVAN: When you fly over the crater, you see so many other larger objects around it, and it does seem a quite intimate object in the larger space of Arizona desert. Of course, you’ve not built the crater. You’ve actually, as you said, found the pyramid. You just built the chambers inside.

TURRELL: Yes.

GOVAN: Your interventions are relatively minimal, relative to the scale of this natural object.

TURRELL: Yes. I should have been a Pharaoh. That would have helped.

GOVAN: Of course, when you’re in Roden Crater, it’s very un-physical. You have used this large device to change the shape of the amorphous ephemeral sky.

TURRELL: Some people will go to the Grand Canyon and feel diminished by the experience, but I feel there are ways that you can be brought to that experience that can be just the opposite. You can actually perceive the cosmos and feel intimately a part of it, so that it doesn’t diminish you and your position in it, but you feel a part of it in a way that is powerful or empowering.

GOVAN: Empowering, because you’re making that experience. Right?

TURRELL: Yes.

GOVAN: The thing about Roden Crater to me is that, in all of this supposed monumentality, which is existing in nature, you’ve put a bit of culture into nature to create a device which essentially empowers the seer to understand their seeing. It is an intensely intimate experience of one’s relationship to something quite large, and to one’s self.

TURRELL: Yes. I mean, art does do that, too, in many ways. Just the appreciation of all arts over the centuries, whether it’s what the Kings of Amarna were trying to do from Akhenaten or even before that . . . I feel to be in the tradition that includes the great exhibitions that happened in the 19th century, when you had painters making dioramas and panoramas.

GOVAN: I often look at your work in relation to those 19th-century spectacles and the beginnings of museums, as bringing nature and natural phenomena into the buildings in a city for a large number of people to experience them. But obviously, Roden Crater is the inverse. Roden Crater brings a bit of culture into nature, to create a device in nature. I wanted to ask you about Andy Warhol. Because this is for Interview. I’ve asked a few artists, like John Baldessari and a few others, about being in Los Angeles in the ’60s, and how, stunningly, Warhol was not a presence at all.

TURRELL: Well, it didn’t have the same bite in L.A. that it had in New York. We were all interested in it, because it is art, and it’s what artists put up with at the time. Of course, that was the period when New York was . . . It wasn’t that it was anti-California art, it actually was kind of anti-any art that was from outside. It was very provincial. But it’s a very huge and powerful province.

GOVAN: But it got such little traction in L.A. at the time. Which is curious because Warhol was obsessed with the cult of celebrity. I guess it was coals to Newcastle in L.A.?

TURRELL: The big thing is that New York is a town of culture. L.A. was a town of entertainment. There’s a big difference. That was often hard for the artists in L.A. at the time, too. But the biggest thing is that we weren’t the sort of number one. But that’s now changing; L.A. is changing.

GOVAN: It’s changing big-time.

TURRELL: I think culture moves from the East to the West only because the time change is easier on you in terms of jet lag to go to the West than it is to go East. So that’s the only reason it moves that way.

GOVAN: I know artists like to complain about the fact that they were rejected in Los Angeles. But essentially, art always comes before museums and before institutions. So it’s not unusual to imagine that the art comes first, the public doesn’t know quite what to do with it. . . .

TURRELL: Well, all of us artists, including Bob [Irwin] and John McCracken . . . we were all complaining—we still complain about it. But it’s kind of over. I’m not going to have a whole lot of artists sympathizing with me. But one thing about Los Angeles is that it was tasteless, and that is freedom because it has no barriers. You need to have a tasteless city, and that’s the problem with New York—a little too much taste. It is taste that is actually censorship. L.A. did not have it, and it was a great place because you could do anything in it. That’s why I liked L.A.—the revenge of the tasteless.

GOVAN: Just to say for the record, is the fact that your work now is all over the Earth. You’ve completed how many autonomous, singular projects that are now accessible in some way?

TURRELL: Seventy-nine in 25 countries and 21 states. I used to say that there was a certain part of my career when I thought, “God, my art just isn’t going anywhere. My art is going nowhere.” But now, the next time you find yourself in the middle nowhere, you’re probably pretty close to my art.

GOVAN: That’s right. I just got back from a piece in Seoul.

TURRELL: If you want to go to this one in this Turrell Museum in Argentina, that’s harder to get to than Roden Crater.

GOVAN: That’s a good one. We need an airplane for that.

Michael Govan is the Director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Click here to see photos of Roden Crater on Flickr