Thunder Strike

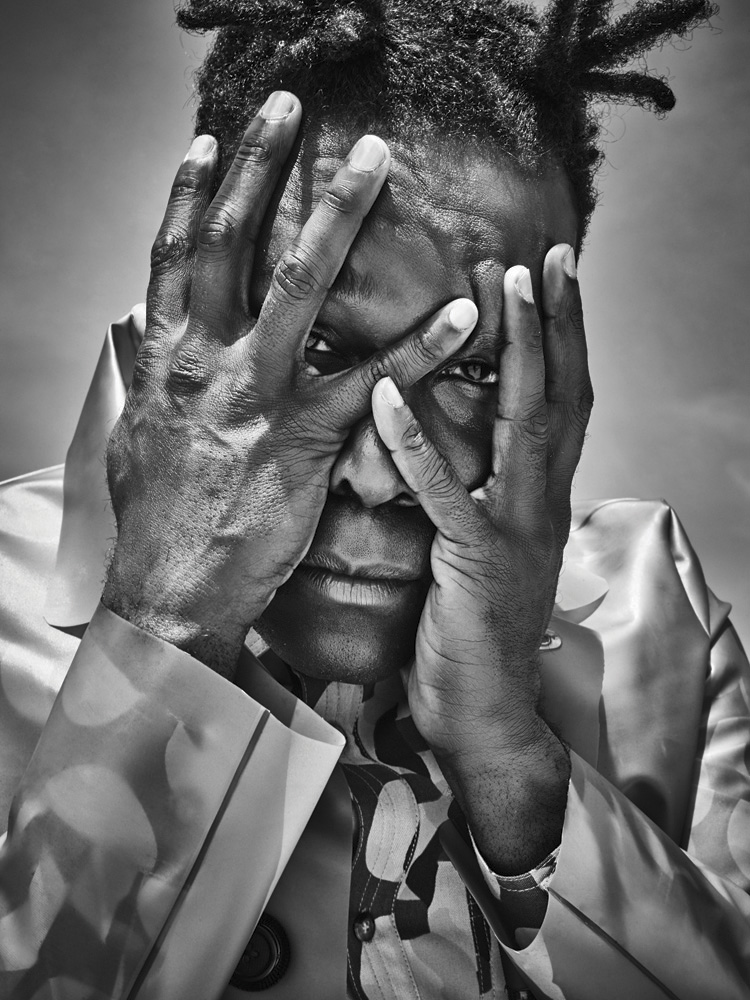

GUILLERMO E. BROWN IN LOS ANGELES, JUNE 2016. PHOTOS: DANI BRUBAKER. STYLING: LEAH ADICOFF & KAROLYN PHO. GROOMING: MAKIKO NARA FOR MAC/WALTER SCHUPFER.

In 2010, Guillermo E. Brown christened himself Pegasus Warning. The name came to him in a dream, but it stuck. After years of working as a jazz percussionist in his native New York—recording and touring with David S. Ware—he moved to L.A., where his newfound mythological veil provided him with the space to prioritize his solo work. “The Pegasus is all about the wellspring of ideas and creation, that thunderous strike in the sky that gives us that aha moment,” Brown says. “It became basically a warning to myself; if I don’t follow those creative impulses, I can get myself into trouble, and I should focus on my solo work just as an exercise to keep myself from going absolutely crazy.”

On September 30, Brown will release PwEP2 (Melanin Harmonique Records), his second EP as Pegasus Warning. It’s a faithful display of his idiosyncratic sound, which takes the form of yearning vocals gliding and vibrating over experimental, electronic backdrops anchored by percussive builds. Relieved, he tells us, “I’m happy to let loose these sounds.” Below, we’re pleased to premiere “Best Thang,” the EP’s first single. Brown co-wrote the track with Jamie Lidell and Kassa Overall, and it’s fueled by a question: “Is there anything that we can do but search for those bits of life that are the most amazing?”

HALEY WEISS: To start off, I’d like to talk about the collection of songs you’ll be releasing in late September. Can you tell me a bit about what your process has been like and what it’s sounding like?

GUILLERMO E. BROWN: I’ve been really trying to focus on the songs and my voice. I always try to hit a few areas when I’m making a record; I want the sounds to be experimental and exploratory, I want the drumming to be distinctive, and I want my voice to be able to shine through. So I’ve been really focusing those elements, and making songs that have some lasting power and some staying power. I want the songs to be able to stand up to the “Casio treatment”—it’s if the song can live just as a song with a foot stomp and a hand clap, or it can go with the bossa nova setting on a Casio, or the latest hybrid dance music form. The song is still there. It’s almost like you can’t fuck up a good song. I’m a big fan of new production techniques and new sounds. That’s kind of what has been my focus out here; making sure that the songs can stand away from the production, however it’s produced. My sound is super hybrid; the acoustic sounds are there and the electronic sounds are there.

WEISS: How did you arrive at that sound? Is it because you’re a jazz percussionist?

BROWN: I think when I was coming up in New York, there are a lot of projects that sort of require both—whether it’s a kind of electronic-minded approach to live drumming, or an improvisational approach to sequencing drums and programming. That’s right down my runway. That’s just where I live and that’s one of the things I became known for in my collaborations as a drummer, [work] that calls for something outside of traditional jazz drumming or traditional MPC hip-hop programming. That’s a super nerdy way of explaining it. [laughs]

WEISS: When you perform, what form does the band take? Are you solo?

BROWN: I come from a place where I feel like the band version of it should be modular. Folks that have seen me along the way—even here in L.A.—see I play solo, I play with a small trio, I play even with an eight piece. … I think of every song like a game. It’s like a video game: “Okay, I’m going to hop over here and if I press this drum, or if I hit this note, then that doorway opens. Oops, I fell down a trap door but I’m in a whole new world.” Some people want to feel comfortable when they’re performing; I’m kind of the opposite. The more uncomfortable I feel, that’s where I know the magic is. I have some comforts; I know the song, I know what’s coming, I know that when I sing there’s going to be something that I’m into, and I know that spirit is the spirit that other humans connect to. I feel this and I know that other folks can feel it too, because we’re humans and we’re communicating even if we’re not speaking in vocal ways; you can communicate by responding with your body or with a hand clap, with a laugh or with a smile, with non-verbal communication.

WEISS: Have you always been interested in creating solo work?

BROWN: I’ve always created solo work. When I first came to New York I was working in a few different areas; I was working as a drummer, a vocalist, an actor, and a dancer. I had gotten picked up more on the music side and that sort of went, and that’s where I found my community in New York and that’s the path that I went down.

WEISS: You’re originally from New York, right?

BROWN: Yeah, I’m from New York. I grew up there. I grew up in Westchester County, the suburbs. For me, that was always the best of both worlds. I was super lucky to have a place where I could pretty much practice drums unperturbed. Obviously there were neighbor’s complaints, but not very often, and I could get to the city easily by myself or with my parents.

WEISS: How old were you when you started drumming?

BROWN: I think maybe five or four. My grandfather was a drummer, so it was always around, and my mom is an ethnomusicologist. At that time she was really focused on that side of her work.

WEISS: What exactly is an ethnomusicologist?

BROWN: An ethnomusicologist is a cultural anthropologist who focuses on music.

WEISS: So did you learn a lot about music from her?

BROWN: Absolutely. My mom and grandfather are my first teachers of music. Those experiences and the process of exploring music as a discipline through them and with them is one of the main foundations of my life as musician.

WEISS: I read that your father is a priest/wizard. I’m curious as to what that entails.

BROWN: [laughs] I call him a wizard because I like to highlight people’s superpowers. Humans have real superpowers and when I see my dad, and saw my dad, work with communities and help people change viewpoints, and lead people in healing and guide them through troubled waters in their lives, that represents to me a real world wizard—if you want to look at it with prismatic eyes. That’s what they’re talking about you read about a magician. Obviously there is magic, too, but when you really sort of uncover it, what are folks talking about? Sometimes in fiction they’re talking about people who have whatever that thing is—it could be a smile that soothes a broken heart. Whatever that thing is, he has it, and that’s what I call wizardry. But he’s actually an ordained Episcopal priest.

WEISS: Was it pretty early on that you knew you wanted to pursue music as an occupation? What other jobs have you had your hand at?

BROWN: This is what I’ve wanted to do for a long time and I don’t think I could’ve gotten this far without maintaining music as my focus. I’ve had a thousand different types of jobs and internships over my time, so it’s not like I didn’t consider or I’m not even still considering what it would be like to open a restaurant or a bar or venue. I’ve worked as an arts administrator, in a chiropractor’s office, for a company hauling gear around New York City, as a graphic designer’s assistant, for visual artists, and worked for and with choreographers as a composer, and as a touring assistant. I can really keep going. [laughs]

WEISS: You’ve cited Grace Jones and Sun Ra as major influences. How have they informed your work? What do you find particularly inspiring or interesting about them?

BROWN: I guess their independent spirit, I’m thinking in the case of Sun Ra, an artist who was able to galvanize a whole community of musicians around his ideas and maintain a large group of musicians for many years which still goes on to this day—the costume, the pageantry, the non-conforming-ness, the nontraditional identity of it. And Grace in the same way. I feel their spirit and their images are so clearly not the norm, that for someone who chooses my path, they’re the planets that you want to go to when you’re taking on a project like this. That’s my thing; I’m not trying to be weird or what have you, it’s just that there’s so much of something else that my thought is, “Why wouldn’t you be opposed to that, whether it’s in your visual imagery or your stance on life?” I think they’re two of the greats, especially in terms of imagery—I mean, sonically as well. But music is so visual now.

WEISS: You used to collaborate quite closely with David S. Ware. How did your work together influence the music you make today? And what were you doing together?

BROWN: I recorded with him, played with his band, and toured with him. Man, that was a trial by fire experience, and learning… He’s another kind of brutally individual sonic being. That experience has stuck with me in terms of at the show, to never be afraid, you have to keep on playing in order to expose whatever the thing is that you’re trying to get. Sweat it out, work it out, it’s there—you just need to keep pushing through and you’ll find it. That’s one of the beautiful lessons I learned working with him in a live setting. I would be sitting, of course, at the drums and he would be standing over me in a way, with his horn facing me, just drums and saxophone. We did that from Hammerstein Ballroom opening for Sonic Youth to some beautiful outdoor amphitheater in Sardinia, the Blue Note [Jazz Club], to Jazz at Lincoln Center, just all over. He never wavered from his approach to music, and never, ever, ever let up. That, for me, is the biggest lesson; just stick to you. That’s the best thing you can do for yourself and for others—to be able to see that and experience that. It’s okay if it’s not working for whomever it’s not working for, because it’s working for someone.

WEISS: How did you become a part of Karen, the house band on The Late Late Show?

BROWN: I heard about the audition through a friend of a friend and I went to the audition. In much the same way as many of my other experiences, the music is based in improvisation. It was Reggie [Watts]’s choice—Reggie was looking to put a band together—he wanted full collaborators, full creative partners in music on the show. That’s how he explained it and I imagined it. I went in and played with Steve, the keyboard player, and Tim, the guitar player, who were already set in the group. We just played, and that’s very much like many of my other formative experiences in music—just playing. That was the interview.

WEISS: What has the experience been like thus far? Have you enjoyed playing on television?

BROWN: Absolutely—it’s incredible. I couldn’t be more elated and positive about it as a musician. I studied with Johnny Carson’s drummer for many years during one of my summers away from home at the Skidmore Jazz Institute, and I saw this guy who had been playing, and he had played with everyone—just many, many years of music. I never even considered it—or maybe I did at the time think, “Maybe I could take Ed Shaughnessy’s job” [laughs]—but however my mind constructed it, here I am in fact walking in part of the path that he and Marvin Smitty Smith laid out for me, and Terri Lyne Carrington, all the drummers from late night who I absolutely adored. I still pinch myself every day, basically; I believe it but I’m still enamored and it’s still joyful and it’s a pleasure to work with everyone at the show. … I think it comes from James [Corden] and Reggie as well. If those are the folks who are the face, the absolute front of the show, it makes a lot of sense that everybody else connected to the show has that same spirit in some way.

PwEP2 WILL BE RELEASED SEPTEMBER 30, 2016 VIA MELANIN HARMONIQUE RECORDS. FOR MORE ON PEGASUS WARNING, VISIT HIS FACEBOOK.