Johnny Marr

The bond Morrissey and I had was that we were both on our own in the trenches for a long time with just hope and only hope . . . and desperation and admiration for each other. Johnny Marr

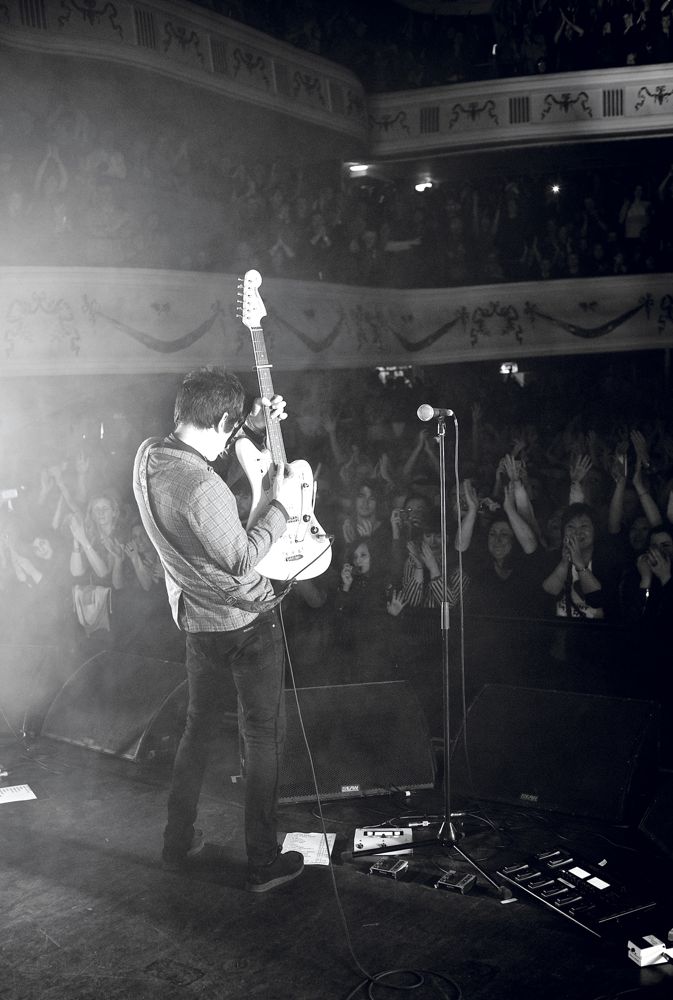

Sometimes the most divine talents are also the most inscrutable. How else to explain why Johnny Marr, guitarist of the incalculably influential Manchester rock band the Smiths, waited nearly three decades to release his first proper solo album? The Messenger (Sire), which Marr unleashed this past February, proved well worth the wait; an album filled with appropriately expansive, inventive guitar work and swooning vocals that has effectively upended Marr’s reputation as a brilliantly humble sideman.

As a teen, Marr, who once dreamed of becoming a professional soccer player, jumped fluidly around various Mancunian punk and rock outfits. One of his earliest bands even won a competition to record a demo with the venerable Nick Lowe (though the result was eventually rejected). In 1982, just before his 18th birthday, he formed the Smiths with a brashly opinionated young poet named Steven Morrissey, and thus the marriage of the ’80s alt-rock equivalent of Lennon-McCartney (though Marr might have preferred Leiber-Stoller) was brokered. While Morrissey got most of the shine, Marr was fundamental to creating the Smiths’ sound, from artfully layering his jangly Rickenbacker riffs into darkly transcendent miserablist anthems, to bringing on a childhood friend, Andy Rourke, to play bass. Over the course of four albums, the Smiths became the definitive British band of their era, with Marr’s guitar ushering in the intricate, melodic pop approach that would define Anglo rock for the next decade.

After the Smiths dissolved in 1987, Marr, then just 23, turned into an itinerant player, hopping from a brief stint with the Pretenders to joining The The in 1988 to forming the alt-dance group Electronic with New Order’s Bernard Sumner. His zealot-like love of studio work also yielded numerous collaborations with the likes of the Talking Heads, Pet Shop Boys, Beck, and Oasis, among others. In more recent years, he has fronted Johnny Marr & the Healers, releasing an album with the band in 2003, and was recruited by tetchy indie rockers Modest Mouse to appear on the chart-topping We Were Dead Before the Ship Even Sank (2007) and tour with them as an official member. He also joined the British band the Cribs for one album, before the lure of songwriting pulled him back to Manchester, where he now lives with his wife and two children and recorded The Messenger.

Marr has certainly packed a lifetime of rock regality into his 49 years, and influenced an entire generation of guitarists in the process. One of them is his interviewer here, Nick Zinner of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs.

NICK ZINNER: I just got back to New York from a tour last night. I’m feeling a little bit shattered. [laughs] It might be a semi-sleepy interview.

JOHNNY MARR: Oh, that’s all right. I got back from tour maybe a week ago, and as soon as the adrenaline left my body, I just kind of went whoosh.

ZINNER: Yeah, when a tour finishes, everything kind of stops and seems to catch up to you.

MARR: I’ve just got a little bit of time off, and I thought I’d demo a few new songs, but other stuff has come up—like, I’m doing a B-side now for the new single … Which I’d totally forgotten about. [laughs]

ZINNER: Do you have your own studio?

MARR: Yeah, the studio I’ve got now I’ve had for more than 20 years, which I guess means I really like it. It’s got a big live room and windows, so I’ve always been really reluctant to give it up. Having your own space is getting rarer and rarer these days. It’s dangerous giving someone like me—who grew up fantasizing about studios and records—the freedom and resources to build your own studio. I would just live in it, which is what I pretty much did for all of the ’90s.

ZINNER: Well, you made some unbelievable music in that time.

MARR: It went okay. We started off doing The The there.

ZINNER: Oh, did you record [The The’s 1989 album] Mind Bomb there?

MARR: I did—most of the guitars on Mind Bomb. That was the first thing we did when it was just pretty much a bedroom and a bit of a sweatbox. But now I’m such a live creature. My mind-set is so much about playing shows; it’s quite surprising. For most of my younger years, I was so extremely into records and the process by which records were made. That’s one of the reasons why I did so many collaborations—because you’d go from one album to another album. But after about 10 years of playing, a fair number of years after the Smiths, it started to dawn on me that my opinion on that was quite extreme because everybody I knew was saying, “Well, then you go out live.” Pretty much my whole thing was, “When I finish a record, when can I do another one,” you know?

ZINNER: Right, you just kept going and going.

MARR: But it occurred to me that I was almost a zealot about what could happen in the studio. I suppose in some ways that’s why my collaborations worked out, because I would go in the studio with such enthusiasm and it would never be a chore for me. I was never itching for the process to be done so we could get out live. It’s a different matter for me now. Now I’ve noticed that I actually have one eye or one ear on how I’m going to do it on stage. And maybe that’s because I’m the frontman in the group; I do believe that any good frontman should be impatient in the studio to get out.

ZINNER: Well, there is a certain immediacy to the new record.

I never took fans for granted. I always assumed subconsciously that people who followed what I did were just people who were kind of like me. Johnny Marr

MARR: It’s funny the way that came together for me. That happened purely because I’d done so much with touring, mostly with Modest Mouse. I think we first met when I was playing with Modest Mouse, right?

ZINNER: That’s right. I think that was six years ago.

MARR: Was that at that outdoor show near Massachusetts?

ZINNER: Boston, exactly.

MARR: Yeah, there’s a picture of us somewhere, like, holding a Jag in a strap.

ZINNER: That was a great photo. Do you like touring now?

MARR: I do. The actual process of travel I really like, because that time on planes and in airports makes me feel like I’m moving around like a ghost. There’s a certain aspect of justifiable downtime. I really feel like being online is so pervasive now. And I’m not blaming any of us for it. But that enforced time when you have to switch off, that you’re on a plane, is so unusual these days. Obviously, I have an iPad and a laptop and an iPod, and all kinds of different movies and distractions. But that’s okay. It’s just that thing of not being able to interact with other people through e-mails or social media or whatever. It’s crazy how you even notice that you’re not able to do that. I find that the kind of traveling that we do—long days, particularly if you go somewhere to do a show, and then traveling again the next day—a lot of people would find pretty challenging, but I find it energizing in a weird way.

ZINNER: Yeah, me too.

MARR: It’s this sense of going someplace—someplace where you assume you’re going to have a good time by playing a show and hopefully being fabulous. But it’s more than that really—it’s just moving through the world. I think one of the things about being around for a while and getting to know yourself is that when you do have these positive experiences, you don’t take them for granted—you identify them and you make the most of them. I don’t know—it’s kind of cool getting old in a lot of ways.

ZINNER: You seem very comfortable with getting older. I really admire that.

MARR: Well, to put it bluntly, if you’ve got things to be fucked up about when you’re younger, it’s just a relief when they’re gone. I think you just learn to not care too much about the opinions of people that don’t really matter. I don’t mean that to be arrogant or dismissive, because I very much care about the opinions of people who do really matter.

ZINNER: It’s more about the energy that you put into that.

MARR: Entirely. Like, I never took fans, as such, for granted. I always assumed subconsciously that people who followed what I did—musicians, people who bought tickets or records or whatever—were just people who were kind of like me. But now I’m more aware of them and who they might be. They’ve all got stories and lives and certain expectations of me, and it’s beyond just gratitude. It’s an interaction. And without getting too corny about it, but the last few years I’ve come to regard them as a strange kind of extended family. Or the good ones, anyway. Don’t get me wrong. Jesus.

ZINNER: [laughs] Yeah, right.

MARR: Some of the audience seem to relate to me that way, in a kind of brotherly or family kind of way. Maybe that comes with being around so long and being kind of on your own. I mean, I’ve got my group, but I don’t feel like I’ve gone through 30 years of being part of a gang. I’ve been in several different gangs, and I have this overall bunch of people who are my comrades, whether that’s Matt Johnson [of The The] or Bernard Sumner [of Joy Division, New Order, and Electronic] or Bernard Butler [of Suede]. It’s definitely a whole bunch of people—Bert Jansch, Nile Rodgers—all of these great, great people who have gathered as musical comrades and friends and so on. But at this point, I think the way the audience relates to me is as Johnny, you know?

ZINNER: Yeah, I think your fans—myself included—feel like we’ve grown up with you, essentially. There are very few people who can do that, who can move from one thing to another but still be meaningful and current at the same time. And not just be one band. So you’re definitely a rarity in that sense.

MARR: I’ve had a lot of interaction with the people I play for over the last few years, which I didn’t do for a long, long time other than through making records.

ZINNER: Did you not tour in that period in the ’90s?

MARR: No, hardly at all. Electronic toured, but I think in total we only did as much as eight gigs, plus 12 for TV. New Order would get together every so often and do a tour, but that was getting rarer. Most of the tours I did in the ’90s were with The The. So that was a big chunk of time for a musician to not tour. And the odd thing is I was never really asked about my touring in the Smiths, because the Smiths toured so much. When I was asked, I think it was a surprise to people that I was the one who didn’t really like touring, because the assumption was that Morrissey wanted to stay in his study reading his books, and that I wanted to be swinging from chandeliers with a bottle of brandy in one hand—which is only half untrue. [both laugh] But now that people can pull back and look at the kind of people we are and what we’ve done, you can see that, actually, the cartoon-like characterizations of us were kind of the opposite of who we are. Morrissey’s main arena, if you like, was in front of an audience, and I was the guy who was much more about making records. I’ve just joined the party very, very late in terms of the concept of the whole live-energy thing and the art of performance. I mean, Karen [O] is a fantastic modern example of the stage being a place to do something very interesting.

ZINNER: She’s phenomenal. She just pulls it out every night that we play. It’s inspirational but it’s unique, too.

MARR: I think it’s a shame when pop culture forgets that theatricality is a big part of it. When Neil Young is fumbling around in his pocket looking for the right harmonica, it doesn’t matter that he’s a dude in the hat who is a man of the people—there’s a theatricality there. You don’t have to be David Bowie or the Kabuki theater to have that theatricality going on. Obviously, people like David Byrne understood that. One of the first things I noticed about being in Modest Mouse, too, was the way that, not just Isaac Brock, but all of us kind of ascended the stage and took our places. I think some musicians can almost forget that the stage is something to do something on, even if that thing is standing still. The Ramones knew it.

ZINNER: Absolutely, they’re the perfect band. [laughs]

MARR: Sometimes people confuse contrivance and authenticity, and sometimes I think authenticity can get in the way of a good excuse to do something theatrical. I just don’t like wasting opportunity—if you’re going to do a photo session, if you’re going to walk on stage, why not make it interesting?

ZINNER: I feel like a concert or a show should always feel like an event. When I was a kid, I got to see Jane’s Addiction open up for Iggy Pop—it was right after Nothing’s Shocking [1988] came out. I was just so transfixed by every member of the band, and I couldn’t figure out if Perry [Farrell] was a boy or a girl. [laughs] The music was so powerful and each of the band members was such a mystery and a powerful presence, as individuals and as a collective entity. It made a huge impression on me.

MARR: Did you already want to be in a band?

ZINNER: I was playing music, but just in my bedroom.

MARR: Is Yeah Yeah Yeahs your first real band?

ZINNER: It’s actually my second real band. I was in a band all through my college years, and we all moved to New York City after we graduated and kept playing for a year or two and tried our best to make it—and we failed miserably. [laughs] When I met Karen towards the end of that band, it was great because I lost all my hopes and dreams of ever becoming a musician. So when we started, it was purely for fun and just a hundred percent hilarity. I think that’s definitely something to keep in mind all the time—like, why you do it. It’s your first band that really clicked artistically that got you noticed, which is what happened with me. I mean, I was running around in all these little bands in the south of Manchester for ages, but they weren’t bands who were on the proper circuit or anything. They were all just bands trying to get good enough to even get gigs. You were lucky if you got a gig in the city, let alone outside of the city. I don’t want to say they weren’t real bands, because they worked hard and took themselves seriously, so it was definitely an apprenticeship for me, but the Smiths was the first proper band with a record deal and any real prospects.

ZINNER: How old were you when the Smiths formed?

MARR: Just about 18, I think. People think we had success immediately, but for what seemed like a very long time, it was just me, Morrissey, and Angie, who was my girlfriend at the time and is now my wife. It was me and Morrissey just writing and trying to get some interest and some momentum. You know, something that never gets mentioned in those silly books and all of that is that the bond he and I had was that we were both on our own in the trenches together for a long time with just hope and only hope. [laughs] And desperation and admiration for each other. It was definitely knocking on doors, trying to find people …

ZINNER: Trying to get gigs …

MARR: Trying to get other musicians, trying to get songs, trying to get bus fare … That never gets mentioned—he and I really toughed it out, just the two of us, for a long time. I’m not taking anything away from the others, but it’s just part of the story, because as a four piece-group, the Smiths got on the label we wanted with the first single, “Hand in Glove”, and etcetera and etcetera. It seems like the blue-tipped torch paper was lit and off we went, but the two of us know that the time before that we were toughing it out with all that hope.

ZINNER: I’m reeling from listening to you talk about the early days of the Smiths. It’s still amazing for me to hear all that stuff.

MARR: Well, it’s nice to talk to someone I actually like about that stuff.

ZINNER: I’m sure you’ve talked to death about a lot of that stuff.

MARR: I mean, it’s usually quite a one-dimensional affair. I’ve been asked to reiterate stuff that is quite dull in the first place. The requirements are often not the deep stuff that people want to know about.

ZINNER: Right. I had a couple questions, but I don’t know if it’s rude to ask. [laughs]

MARR: Go on.

ZINNER: First of all, I could never believe that the Smiths were only around for five years, because it’s just unbelievable how much music was put into that. There was such an active tie in the U.K. music scene, especially in Manchester, so I’m curious what other bands you were playing with?

MARR: One of the things you and I talked about late one night, in New York perhaps, was that in the late ’80s and early ’90s, I would be asked by DJs—remember them?—about how dreadful the ’80s were and how the Smiths and New Order were anti-that. That was just so boring and obvious. It was me just saying, “Well, of course Duran Duran were hanging around on boats and we weren’t about that,” and “Spandau Ballet were making ridiculous videos and playing saxophones, and we were rebelling against that.” But that’s a one-dimensional setup position. What I really wanted to say was that being 17 or 18 when the band started out, around ’82, was very much about the Gun Club and the Cramps, who I still love to this day and still listen to. So sure, what I wanted to do was against whatever was going on that was cheesy and dominating the charts, like anyone who is interested in what’s alternative or underground. But the stuff that led to me to form the Smiths we were actually for as opposed to against—it was really fucking cool. I know we’ve talked about Rowland S. Howard and those Birthday Party shows and some of the early Fall gigs at that time … I saw everybody. We weren’t sitting in a corner of some library hating on everything. You are part of your youthful wave—or you should be.

ZINNER: Yeah.

MARR: I suppose it’s easy for me to picture all of this stuff because a lot of it happened in one specific place, the Haçienda. When I think of the Birthday Party gigs, the Tubes gigs, that sort of quick succession, they were at the Haçienda. It seemed like you couldn’t go to the Haçienda for a week without seeing New Order hiding in green light. And this was years and years before the place was packed to its rafters; it was mostly empty and felt quite elicit, super-industrial. I believe that was where the Smiths played maybe our third gig, and then our seventh. So we were intrinsically tied in with that place and a lot of those people without actually being on Factory Records. But to get back to your original question, I played in a band who were a proper bunch of terrible reprobates called Sister Ray, whose singer [Clive Robertson] was this real wild, fucked-up fellow, and they managed to get themselves on an underground compilation LP. So that was very exciting for me, because I was only 15 and they’d actually been on vinyl with a song called “Suicide.” I played with them for about seven, eight months, knowing that I was in a pretty perilous situation. [both laugh] My parents were not at all pleased that I was hanging out with these guys. But I had to hang out with them because I inherited a thing called a Colorsound Tone Bender from the guitar player who had left.

ZINNER: What is that?

MARR: It’s a really gnarly, strange, modulated fuzz pedal. So that was a big reason for me to stay. We used to rehearse in this horrible, dank, dark cellar, but we were able to play at super-loud volume, and it was kind of like this proto-studio. I felt that I had a lot to learn from playing in that band, mostly about playing at high volume and being around guys who had actually played concerts and been around a bit. But they were just too crazy for me to stick with them. It was quite amusing‚—I was so young that I got in the newspaper for just being in that group. It was some story like, “Teen freak virtuoso joins old druggies.” [Zinner laughs] And then I found myself in a neighborhood band whose leader was insanely talented as a writer. His name was Rob [Allman]. He was one of these guys who knew how to write songs with 25 different parts in them, all of these chord changes—he was a really clever pop writer. I was in his band a couple of different times, and for a while he was going through a folky, psych-folk sort of phase, and that’s how I got into Bert Jansch. That was really a game changer for me. Sadly, Rob is not around anymore. He ended up getting into substance abuse. Very sad story. That was not the first or last time I saw that … Well, it was the first time but not the last.

ZINNER: Unfortunately …

MARR: There was another incarnation of that band when he was very into XTC and Blondie and was writing all these songs in that vein, and I was expected to sing good backup and play pretty good guitar a few times a week. Like I said, the people I was in bands with took it very seriously. It was an unusual neighborhood. It was the biggest housing estate in Europe—I think it probably still is—which just weirdly was home to a bunch of working-class kids who were very into playing the guitar. It was almost like a salon of these guys who would sit around dissecting everybody’s music of the day, being quite competitive. One guy’s specialty was Pete Townshend and Mick Ronson—he turned out to be Billy Duffy, who formed the Cult. Billy would have been 16, I would have been 13.

ZINNER: Amazing.

MARR: Another guy was really into Neil Young and Richard Thompson, and another guy was really into Bill Nelson. We each had our specialties. And so when the New York guitar players happened, that was a real game changer. Suddenly, the guy who was into Neil Young and Richard Thompson was really attracted to Tom Verlaine. Billy went nuts over Johnny Thunders. And I inherited James Williamson from the Stooges—Raw Power [1973] became my touchstone. These guys were older than me—they had officially left school—and I’d be hanging out with them every night, trying to hold my own because I could play some of these riffs. They’d talk about, “Tomorrow I’m going to hang out in Virgin Records,” or “I’m going to buy some tickets for the Heartbreakers tomorrow,” or whatever it was, and I’m sitting there in a school uniform thinking, Fuck me.

ZINNER: [laughs] You guys were somewhere between a gang and a club.

MARR: Exactly. We were all 100-percent committed to this. And I think what happened, though, was that some of us—specifically Billy Duffy and myself—were more desperate than the others. Same with Mani [Mounfield] from the Stone Roses. I didn’t actually hang out with him, but he was connected to my family because they came from within a couple miles of each other. That’s again an uncanny thing that someone from my childhood went on to stick it out in a band.

ZINNER: It is, but it seems like you guys have that sense of urgency. It was all that you were consumed by and all that you had. And it was your identity, too.

MARR: Absolutely. Well, what about for you? Was it your identity?

ZINNER: Yeah. There hasn’t really been any radical changes; I feel like my core is still the same. I grew up in the suburbs of Boston and started playing my mother’s acoustic guitar when I was, like, 13 or 14, and then I got an electric guitar, and all I did was come home from school and play in my room. And there was an older group of kids, too, who similarly took me in, and we would jam in one of the kid’s basement. They liked me because I could play guitar well—I could play Led Zeppelin riffs, I could solo fast—and that impressed them. But that’s all I did. I had, like, two friends.

MARR: Were you drawn to photography when you were younger?

ZINNER: I got into photography when I was in, like, my junior year of high school. I took a class and pretty much just never stopped taking pictures. I loved the way that I could document a moment in time but also manipulate that moment to try to make something more out of what it was.

MARR: Do you keep a journal?

ZINNER: No.

MARR: I tried this year for one last time to keep a journal, because I thought it would be interesting and there was plenty of stuff going on that I would want to write down. Just like I’m talking to you now, late in the night: “Spoke to Nick.” I diligently did it for the first few months, and then I started to fall off a little, and I was disciplined enough to go back and fill in all the blanks. But I actually decided that I just didn’t like it.

ZINNER: [laughs] Right.

MARR: I was definitely not going to look back at specifics and read whatever stuff it was. Now, I’m happy to say so many great things happened to me that I’m very grateful for, that are worth writing down. You know, like when we closed the NME Awards and Justin [Young] from the Vaccines got up with us, and Ronnie Wood got up with us and played his out-there psychedelic blues solo. And last week, just hanging out with Ian MacKaye from Fugazi for a long time after the show. But there isn’t going to be a situation when I sit down and read that stuff. I know what you’re saying about your photography, because when you take pictures, it can say more. I admire people who keep journals, but it almost felt toxic for me to be holding on to this stuff. So I don’t know … Maybe I need to get a couple of more apps for my phone.

NICK ZINNER IS A MUSICIAN, DJ, AND PHOTOGRAPHER. HE IS THE GUITARIST FOR YEAH YEAH YEAHS.