Sundance’s Everyman Benjamin Button

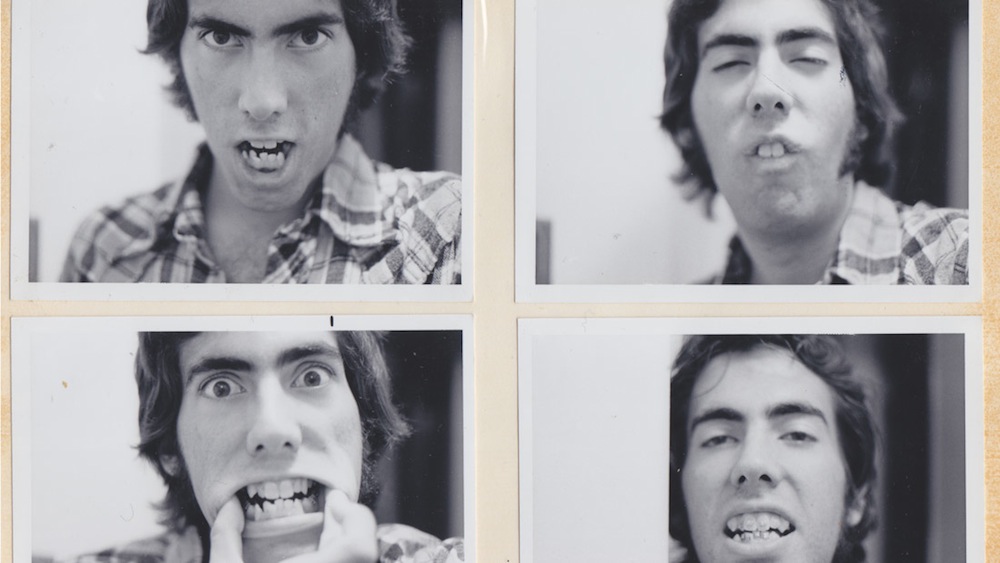

ABOVE: SAM KLEMKE IN SAM KLEMKE’S TIME MACHINE

In 1977, a teenager named Sam Klemke began what he described as an “annual personal status report,” a brief video recap at the end of each year with the intention of “stimulating growth and improvement.” Klemke’s first updates are brimming with bright-eyed hopefulness of the future: “Now at the age of 19 things are really looking up for me, and I predict that this coming year will be the year that was,” he proclaims. But his ambitions never quite materialize, and he slowly unravels into despair in 1981 (“Basically my life is a fucking mess physically, socially, mentally, and financially”) followed by an even deeper desolation (“The best way I could describe 1983 is pathetic”) as his obsessive food consumption, dalliances with prostitutes, and failure to maintain a consistent job looms over him. He has moments of maturity (“The stage is set now, I’m poised for greatness,” he says confidently in 1988), and eventually falls in and out of love, challenges his demons, becomes self-sufficient, and makes positive efforts to live a happy and fulfilling life.

Over the last four decades, Klemke has filmed over 200 hours of his life. In 2011, he uploaded a six-minute selection of it onto YouTube and created a hit viral video, “35 Years Backwards Thru Time.” Among the million or so viewers of the video was Australian writer and director Matthew Bate who, with his team at Closer Productions, contacted Klemke about acquiring the footage for a documentary.

Titled Sam Klemke’s Time Machine, Bates’ intimate portrait of Klemke’s “everyman life” will premiere this week at the Sundance Film Festival in the experimental “New Frontier” category (other entries include Doug Aitken’s first full-length feature Station to Station and Guy Maddin’s The Forbidden Room with Udo Kier and Charlotte Rampling). There are many potential adjectives viewers can use to describe the documentary: raw, uncomfortable, honest, troubling, or even optimistic. The underlying question of the film begs: what does it mean to be human?

We telephoned Bate last week to discuss the ethos and the making of the film—we were in New York, he was in Adelaide.

DEVON IVIE: Are you excited to go to Sundance?

MATTHEW BATE: Yeah, I’m very excited. We were there in 2011 with another film, Shut Up Little Man!, I just described it to someone the other day as film camp for film nerds. It’s an amazing, condensed little happening. We’re really excited.

IVIE: How did you first stumble upon Sam’s project?

BATE: I found him on Facebook. A friend of mine had posted the viral video Sam made. It showed this “obese schlup,” as he calls himself, doing this yearly update. He grows young, kind of like Benjamin Button, and he evolves from this cynical 50-something into this good looking and optimistic young guy. I loved the video. I thought it said a lot about my life; I sort of saw myself in him. It said a lot about mortality and memory and the act of recording. I thought it was juicy material for a film.

IVIE: So you were the one who made the first contact with him.

BATE: Yeah. I contacted him through YouTube after watching the video a few times. I had a sudden knee-jerk reaction to it. I wrote to him through the YouTube account and said, “Wow, we should talk about making a film.” I thought to myself, What else was he recording? More than just that? So I dug deeper and it turned out to be the tip of this enormous iceberg.

IVIE: Did it take some convincing on your part to get Sam to hand over the footage, or was it a relatively easy process?

BATE: Well, it was relatively easy. I sent him my other film Shut Up Little Man! Sam is a caricature portrait artist by trade, and he loves the comic book world, like Daniel Clowes and Robert Crum. Luckily, in Shut Up Little Man! we featured a few of these people, like Clowes and Ivan Brunetti, both of whom are superstars in the graphic novel world. Not only did [Sam] like the film, but the fact that these guys were also in the film served as the catalyst. [laughs] It was the passport that I needed to get into this life.

IVIE: How many hours of film do you think you received from Sam?

BATE: Oh god. I think…can we try to estimate? Probably 150 to 200 hours. A lot of stuff. There has been no limit to him about an amount to shoot. It got worst as we went on, weighing through the banal footage and then finding these little pots of gold.

IVIE: Walk me through a typical day in your offices when you were sorting through Sam’s footage. Did view it chronologically, or was it more of a miscellaneous free for all?

BATE: [laughs] It’s funny. He did an okay job of naming these clips. We got these hard-drives in the mail. He called it something like a “time grid.” He has an amazing ability to recall where he was in what year. So it actually came quite well catalogued. We basically grouped it by year and by decade, and then tried to put it in some kind of chronological order. So we ended up building these enormous chronological yearly timelines. We spent a year putting these timelines together. When I went into the edits with my editor I think we narrowed it done to 12 hours.

IVIE: How many people were on the team sorting through the footage?

BATE: It’s very small; we have a small operation at Closer Productions. Initially a guy called Raynor [Pettge] and I would scan through footage when I would get a drive. I would give it to him, compile an enormous timeline, and then I would sit with him and comb through it again so we could pick and choose what we wanted. It was a strange process. There were really only three of us—Raynor and I as the initial filter and Bryan [Mason] and I as the editing team.

IVIE: I’m curious if Sam specified if there was anything he really wanted to be shown in the film, or contrarily, anything that he absolutely didn’t.

BATE: The beauty of Sam is that he’s very uncensored. I see him as the pioneer Facebook status updater. He’s the guy who decided he would status update his entire life before it was cool. The thing about Facebook is that it’s very curated. None of us put up the kind of things Sam does in his footage; we don’t admit to the things that he admits to doing. He becomes obese, sees prostitutes, stuff like that. I’ve never seen a Facebook update where my friend says, “Oh, I’m having trouble with prostitutes.” [both laugh] It just doesn’t happen. Facebook is very centered, curated, and self-conscious, and the beauty of Sam is that he’s very un-self-conscious. He was very open. He sent material that we couldn’t include in the film because it was too risqué, too personal. So actually, we were the ones censoring things because we knew it couldn’t be on film in a cinema.

IVIE: You didn’t want that X rating stigma?

BATE: That’s right, and it would’ve been. He’s with…these ladies…and he’s filming it. [laughs] He was very open about everything in the film. I was like, “Are you sure you’re okay with this?” He was absolutely fine with it.

IVIE: The evolution of the Voyager 2 space probe is also a central part of the film. What was your reasoning behind juxtaposing Sam’s footage with it?

BATE: Originally, I was making a separate film about the Voyager and I was really obsessed by it. I thought it was an amazing thing that NASA had done, a poetic idea to send this in space to contact aliens. And I’m a vinyl collector, so the idea of the record was very enticing. I had this realization that they both launched in 1977. Sam declares in 1977 that he’s going to create this life-long project and do these status updates and describe the evolution of his life. And then I found parallels between these two characters. They’re both self-portraits in a way; I think the film is about self-portraiture. Voyager going into space is the ultimate attempt by NASA of creating a self-portrait of humanity. NASA’s version is very sanitized, and it’s very high-high with Bach and Beethoven. And meanwhile on earth Sam is stuck in bed for a year eating nachos and masturbating. It’s amazing the juxtaposition between the way NASA was portraying us to aliens, sending this eternal time capsule into space, and the reality being back on earth is that we get addicted to nachos and we masturbate and we go and see prostitutes, and we get fat and fall in and out of love. I found this lovely parallel between the cosmic and the Internet.

IVIE: I’m going to ask you a question that Sam asked the audience in the film: if you don’t produce creativity, are you truly creative?

BATE: That’s heavy. I love that scene in the film; he’s almost at his lowest end. He’s in his parent’s basement and has these creative urges, but doesn’t know how to unleash them or what to do about it. “I want to be creative, but I’m not doing anything.” I remember feeling that exact thought. He’s in his twenties at that point, but I remember being 15 or 16 in my bedroom and wanting to be creative. I have working class parents and the arts weren’t really a big thing where I came from. I had no idea where to unleash the spirits within me to be creative, and I felt such compassion for him at that point. I totally understand where he was coming from. I think you can be creative—you can have the urge and desire but it’s about doing it and finding a place to unleash it. Part of the reason I wanted to make this film is that Sam wanted to be a big filmmaker, like Woody Allen, and feels like he failed. But I don’t think he did. I think the fact that he turned the camera on himself, and captured that moment that we’re talking about, is creative. Okay, you didn’t create Citizen Kane, but in a way you kind of have. To me, anyway. He created this punk-rock Citizen Kane, this self-portrait. I use the word “punk” going back to my record collection. Punk is a really interesting word, I think of it as a “do-it-yourself outside of the mainstream ethos,” which he completely embraces. When I think of the Voyager as the A-side of the record of humanity, then Sam to me is the punk-rock B-side.

IVIE: What do you hope people will most take away from watching the film?

BATE: I hope that they would see themselves as Sam. Even though you may hate him or love him, you see yourself in his struggle —his coming to terms with getting old, with failure, with these aspirations that don’t come true. When we’re young we have these aspirations that we’re going to be rock stars, or we’re going to do this that and the other, and for a lot of us it doesn’t happen. But there’s still great joy in life. Sam doesn’t do anything “great” in his life—he doesn’t become President or make a great film, but he has great, operatic moments. Although we might not become these famous or great people, we’re worthy and have lots of worthiness. That’s what we’ve done—we’ve elevated him and showed him as an everyman, an every person, and when you put his life under a microscope, it’s fantastic. I hope that you can see yourself and your own life through him.

SAM KLEMKE’S TIME MACHINE WILL PREMIERE FRIDAY, JANUARY 23, AT THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL IN PARK CITY, UTAH.

For more from the Sundance Film Festival 2015, click here.