Mike Smith, Drawn Out

“Animation is a great art form,” says Mike Smith. “Ever since animation first appeared, it was very creative, and anyone who touched animation would find their own selves,” he continues. “It’s been ill-recognized; it’s not really thought of as art, but in fact, it’s one of the greatest art forms people have come up with.”

Mike Smith is an artist and an artisan. An animator for over 30 years, he has worked on commercials for giant brands such as Nike and Coca Cola; music videos for David Byrne, Grace Jones, and Bob Marley; and animated and live-action feature films. He has directed a BAFTA-nominated short; storyboarded for Francis Ford Coppola, Curtis Hanson, and Zack Snyder; and animated sequences in Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers (1993).

Born in London, Smith originally aspired to be a classical painter. “I spent a lot of time in my bedroom painting in oils,” he reminisces. “But when I went to college, the fashion was much more modern.” In 1977, Smith followed a friend into an animation program. “I didn’t know what animation was, so I went along and showed my paintings,” he explains. “They had very few people applying, so they took me on.” To pass the course, Smith had to complete his own animated short. “Nobody there showed you how to do it, but I had a go. That’s when I started doing animation, and I’ve been doing it ever since.”

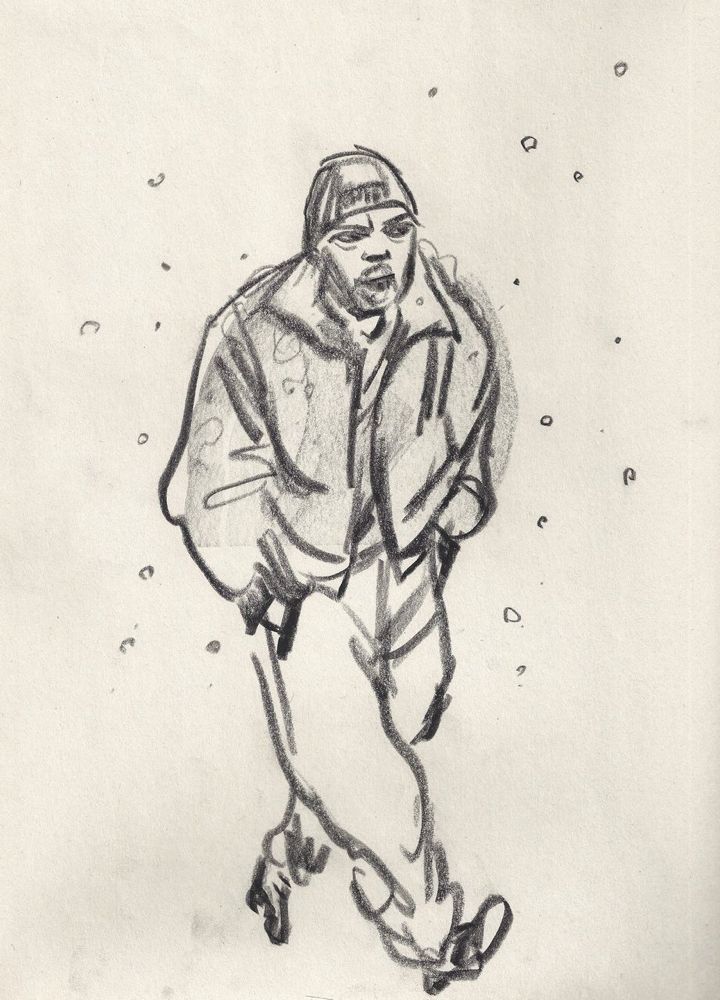

Smith’s most recent film project is The Motel Life. A somber tale of two itinerant, orphaned brothers, The Motel Life stars Emile Hirsch, Stephen Dorff, and Dakota Fanning, and is directed by real-life brothers Alan and Gabe Polsky. Together, Frank (Hirsch) and Jerry Lee (Dorff) escape through fantastical stories—they imagine themselves as cowboys and pilots, fighting Nazis and pirates. Through the lens of Jerry Lee, Smith illustrates the brothers’ tales. His swift, sketch-like animation infuses the film with a human touch and a childlike hopefulness. Frank and Jerry Lee are transformed from just another pair of wasted youths in Reno, Nevada into lost boys out of Peter Pan.

We spoke with Smith, who now resides in Oregon, about his life’s work and plans for the future. “I’m not exactly sure what you want to talk to me about,” he greeted us on the phone. “But I’m happy to talk to you.”

EMMA BROWN: I was looking at your IMDb page. They seem to have left a lot out.

MIKE SMITH: Yeah, I gave up on IMDb. They once included that I was in a 1970s live-action show as an actor. I tried to get in touch with them and tell them I’m not the guy, but they refused to take it off.

BROWN: How has animation changed since you started out?

SMITH: It has changed a lot, but it’s mainly because of technology. I’ve survived it because people like hand-produced animation. I come from a 2-D background. I don’t really do computer animation—I’ve directed it, I’ve designed for it, and I’ve storyboarded it. That’s how I get a lot of my work in animation. When The Motel Life came along, they wanted me to come up with a drawn style, so when jobs like that come along, I really jump on the opportunity to do some stuff. It’s a very enjoyable thing to do.

BROWN: Are you often approached to animate sequences in live-action films?

SMITH: Not all the time, but throughout my career it has happened to me quite a few times. I’ve not grown up in the industry like many of my friends—Disney animators, or animators at major studios. I have worked with major studios, but generally I like more sort of edgy, quirky sort of things that come out of projects like The Motel Life. I’ve done animation for Oliver Stone in Natural Born Killers, and I did two animated sequences for Tank Girl. I’m not saying any of these movies are great movies—or good movies, or whatever—but it’s really fun to work on projects where they leave you with your imagination. Sometimes it doesn’t work out. I worked with Curtis Hanson and I storyboarded four or five major sequences for 8 Mile, which was the Eminem movie in Detroit. Unfortunately they couldn’t come up with the funds, so I only got as far as boarding. Quite often, I’m involved with the idea of it, but then the reality kicks in and they can’t afford it or whatever reason. It’s always fun to do. The nice thing about working with Alan and Gabe is that they have a film that’s close to their heart, and they invite people like me and want me to bring something to the table to enhance the film.

BROWN: Did Alan and Gabe present you with the script? You are essentially inhabiting Jerry Lee, one of the characters in the film, through your drawings.

SMITH: I read the script—Alan and Gabe sent the script—and I loved it. I thought it was a brilliant script. They explained how they thought it would work, and it was written roughly into the script where the animation would be. They were very nice to me; they said, “Just do it how you see it.” I kept it within a certain arena that they were interested in, but I was allowed to be creative within that. I had to come up with a style that would make it feel hand-drawn, but they wanted some sort of depth to it as well. Something a little more substantial than just a drawing, which is why I added textures, a tiny bit of color, a little bit of depth and focus, just to give a little added bonus to the drawing.

BROWN: They sent me your sketches. I love that some of them are drawn on lottery tickets or over notices from the City of Reno.

SMITH: Yeah. They sent me a laundry list of what kind of things they would like, and I basically either followed that or came up with new ideas and just did as many drawings as I could. I don’t get to do art very often, but I did a lot of the drawings on charcoal and paper. The ones you just mentioned, they sent me some materials from Reno and I just drew on top of that and made little scenarios. It was a lot more of that than we got to use in the movie.

BROWN: Have you seen the final film?

SMITH: Yes. I saw many of the rough cuts. One of the things about Alan and Gabe is they formed a relationship with me; they would send me rough cuts of areas of it and ask me what I thought. I was really touched that they would consider my opinion. I knew it quite well, but even when I saw the final film, it’s much, much stronger than the rough cuts. The cinematography is fantastic—I love the look of it. They did cut a small amount of animation, but I think that made sense. I thought Stephen Dorff’s performance was amazing. I think they’ve made a real gem and I think for a first, debut movie it’s really great.

BROWN: How did working with Alan and Gabe on their first feature compare to working with someone like Oliver Stone, who is so established?

SMITH: But Oliver Stone was crazy. He was very experimental. Natural Born Killers was very experimental; it was almost like a surrealist movie.

BROWN: Is there anything you haven’t done that you would like to do in the future?

SMITH: Yeah, I’d love to work on a feature. I’ve directed just about everything except for a feature. I’m in sort of a chicken-and-egg situation where many of the major studios, if you haven’t directed one before, they’re unlikely to give you a chance to direct. On the other hand, directing a feature in a major studio means that you’re basically conforming to what everyone makes. Although there are a lot of benefits to that, one of the nice things about working with live-action people, is that you’re working on something unusual, for animation. I prefer the unusual.

THE MOTEL LIFE IS OUT NOW IN LIMITED RELEASE. FOR MORE ON MIKE SMITH, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.