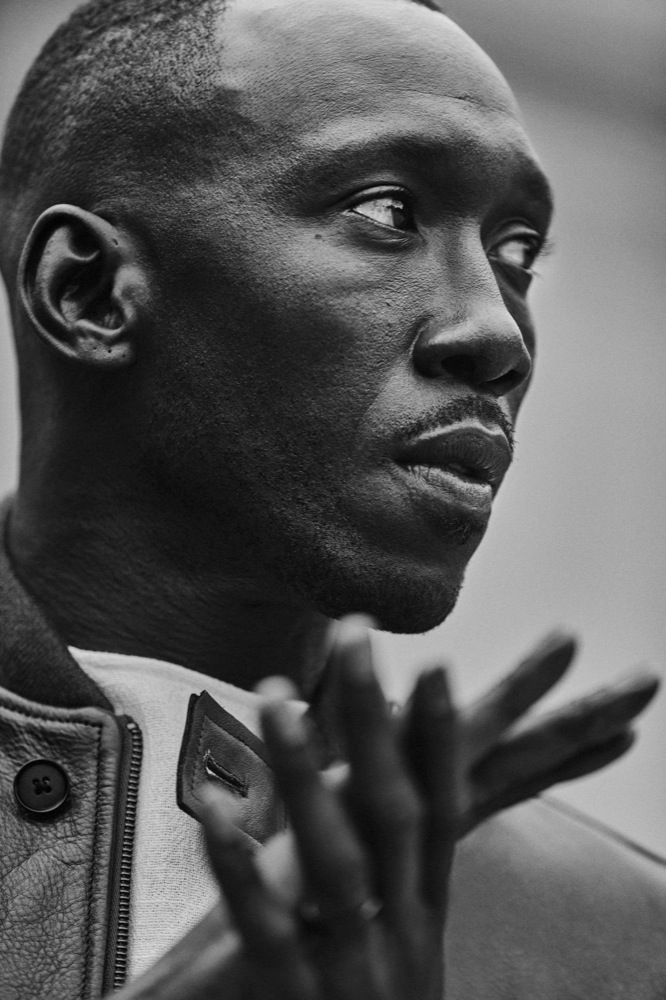

Mahershala Ali

MAHERSHALA ALI IN NEW YORK, OCTOBER 2016. PHOTOS: ANTHONY BLASKO. STYLING: BRITT MCCAMEY/HONEY ARTISTS. GROOMING: JORDAN BREE LONG/STARWORKS USING LA MER.

“I thought it was the best thing I had ever read,” says Mahershala Ali of his new film Moonlight (A24). If you’ve heard any critics talk about Moonlight, which debuted at Telluride and screened at the Toronto Film Festival last month, you’ll know that Ali is not exaggerating. Compassionate, intimate, and graceful, Moonlight follows Chiron, a young African American man struggling to find his place in the world. Directed by Barry Jenkins and based on an unpublished play by Tarell Alvin McCraney, the film is divided into three acts, with three actors inhabiting Chiron at different pivotal moments in his life. When we first meet him, he is a silent elementary schooler nicknamed “Little;” in Act Two we find a gangly teenager in ill-fitting clothes. In the final chapter, Chiron is a muscular gangster named Black—at once the closest and furthest from his true self.

Throughout his story, Chiron is cripplingly isolated. His mother has her own issues with drug addiction; his father is never mentioned. His peers mercilessly torture him, singling out his nascent sexuality. One of the few glimmers of hope in his life is Ali’s character, a local drug dealer named Juan who goes out of his way to befriend Chiron. “We just all really wanted to do service to [Barry’s] story, to Tarell Alvin McCraney’s story,” Ali explains of the film. “We all feel most alive when we’re connected to what we love and what we feel passionate about, and you could definitely see how passionate and how focused Barry was,” he continues.

Out in select theaters tomorrow, Moonlight is working its way towards the Oscars, with Ali in the running for Best Supporting Actor. It is the highlight of what has already been a stellar year for Ali. Though he has been working consistently since he received his MFA in acting from NYU, the 44-year-old Bay Area native wasn’t widely known until he was cast as Remy Denton on House of Cards. Over the summer, he appeared opposite Matthew McConaughey in The Free State of Jones. Last month, he helped crash Netflix as Harlem villain Cotton Mouth in Marvel’s Luke Cage series and lent a commanding presence to the indie film Kicks.

We spoke with Ali last week.

EMMA BROWN: I didn’t realize that your dad was on Broadway.

MAHERSHALA ALI: Yes, he was. He moved to New York when I was three years old. Are you familiar with Soul Train? Soul Train in the ’70s was huge. They used to have this national dance contest and my dad won. He won, like, $2,500 and this red sort of sports car. He ended up moving to New York and he got into dance theater in Harlem. He started working on Broadway and traveling and doing musical theater and shows for about 20 years until he passed away.

BROWN: Was he a self-taught dancer? Had he had any professional experience when he won the Soul Train competition?

ALI: No, he was a self-taught dancer. But once he moved out to New York he started studying ballet, jazz, tap, and contemporary dance. He went to the Dance Theatre of Harlem and studied under Karel Shook, who was one of the best ballet teachers in New York City at that time. Pretty soon—I was about four or five and I remember talking to him—he was in Amsterdam and Japan, traveling the world. He very quickly got into the business and worked as a professional, doing that for the rest of his life.

BROWN: When you were staying with him in New York, did you go backstage at shows?

ALI: Oh, yeah. I traveled with him when I could. There was a show called Dreamgirls, which they recently made a film about, it won six Tony Awards at that time; he did that on Broadway, then he did an international tour of it and a national tour. I would be backstage and I’d memorize the entire musical. I knew several of the actors, many of which have film and television careers to this day, and sometimes I run into them working. But I’d be backstage and hanging out with folks in different cities. I remember going to Toronto as a kid. Once I was out of school in the summer, it just would depend on where he was. Most often I would see him in New York City.

BROWN: I know that you when you first went to college, you wanted to be a basketball player. Was acting in the back of your mind at all having been exposed to your dad’s career growing up?

ALI: When I went to school, I had never even imagined being on stage or acting in any capacity. I was writing quite a bit. It’s sort of a therapeutic accident; I was writing and dealing with my own personal stresses and things that were going on for me as a teenager. I wasn’t sleeping well at all, and just processing some stuff that was going on. So I’d be up all night writing these poems. I eventually started to perform them, especially when I would go visit my dad in New York. And they were essentially monologues. So if anything, I thought I was going to be a poet. [laughs] I used to write these publishing houses and send my poetry to them. I wrote literary agents letters—some of which I still have—trying to see if I could get a literary agent. Sometimes they’d respond to me and compliment me on my poetry, telling me that they didn’t really represent poets or whatever, but encouraging me to keep going. I thought I was going be a writer going into school if basketball didn’t work out.

BROWN: Do you still write?

ALI: Not really. I’m starting to shift that energy and attention into writing a script and trying to merge the worlds. But I don’t write enough, no.

BROWN: Are you a good dancer?

ALI: [laughs] Not the dancer my father was. But I could dance in my time when I was clubbing back in the day. I used to b-boy a little bit, breakdance when I was growing up. Throughout high school, I actually was a good dancer and was in a little competition with a good friend of mine who’s in Aladdin, James Iglehart. He’s a Tony Award winner, we grew up together, and he’s the Genie in Aladdin. When we were in school we were in this little group and performed at some talent show together. I would dance and perform and do little things just at family functions, but that’s just what families do in general: put on music, family’s sitting around, and people start dancing. Nothing that was really all that serious.

BROWN: So when you graduated from NYU with your MFA in acting, did you think that you wanted to do theater in New York or were you more interested in film and television in L.A.?

ALI: At that time—because the industry is different now—you didn’t see people who were able to do television and film. In 2000, when I got out of grad school, it was still a time where people did either/or. So coming out of school, I had hoped to perhaps do theater and film, but with an emphasis on film. Being from California, I didn’t really have an attachment to New York like that—I didn’t have an issue with leaving New York, because it had always been in my life and I knew it wasn’t going anywhere. I had two jobs coming out of school, I did a play: The Great White Hope. I played the boxer Jack Johnson. And I was the lead in this indie film. Then I moved to Los Angeles because New York was cold and it was really too quiet for me at that time. I was out of school; I was hungry. The auditions were trickling in and I was antsy and ready to go. I had just spent three years being in class 12 hours a day, 6 days a week and always doing something, so I didn’t understand being out in the real world and things being slow for a month, or only having one or two auditions. That didn’t make sense to me. I moved out to Los Angeles, and in a couple of months I ended up booking a pilot. That’s how I really found myself in television. I ended up on a show called Crossing Jordan, and I did 19 episodes in the first season. That really is the start of my journey working professionally.

BROWN: Moonlight is such a beautiful film. How did it come into your life?

ALI: I was at my agent’s office and several different people came up to me and said, “Man, you’ve gotta read this project Moonlight. There’s a part in it for you. There’s several parts in it, but there’s a part you’d be good for.” There were probably three or four people who mentioned Moonlight just in the time that I was in the office. So there was a real buzz about the project. I was a fan of Barry [Jenkins] because I had seen Medicine for Melancholy—that was made in 2008, and I was living in the Bay Area at the time, so I really connected to it because it’s a film about gentrification in the Bay Area. The combination of the buzz that preceded me even reading the project to actually getting to sit down and move through this story and have such a visceral response to it, I was definitely happy to sign up.

BROWN: The film is divided into three acts, and Juan only appears in Act One. Were you sad at all that you couldn’t be around for more of the story just because it’s so beautifully told?

ALI: [laughs] I think selfishly, as an actor, we always want to do more. But in this case—and uniquely in this case—I appreciate Juan disappearing because of what that allows the audience to feel. What I’ve heard is that people miss Juan’s presence, and I’m assuming especially in that second story when Chiron is going through so much. To have Juan there to support him, I think things would have been so much easier for him. So the fact that we know that there it is, this other person who was a respite for him, a champion, someone who supported and loved him and held him up … and that that source of light for him is no longer present, I think makes everyone that much more uncomfortable. I believe the film needs that. Not just for the audience, but you also get to see how much of an island Chiron is at that point [during what] most people would reflect on as the most difficult period in their lives. Gay, straight—whatever—adolescents in high school and coming out of junior high, that’s such a difficult, awkward period and kids can be so cruel and mean. So to not have Juan at that time, I think it really allows for us to see just how difficult this journey is for Chiron. And these are elements that are pulling from Tarell Alvin McCraney’s life and from the life of Barry Jenkins.

I know it’s a long answer, but really what I’m saying is that Juan’s disappearance really has purpose. In other projects I’ve been in where I’ve in some way disappeared for 40 minutes of the film and maybe pop up in the end or die early on, there isn’t always a great explanation or reason for it. This feels necessary to me, because I think there’s a greater potential to affect the audience and raise the stakes. People really needed to understand how alone this young man feels.

BROWN: What do you think that Juan saw in Chiron that inspired him make this effort to connect to with Chiron?

ALI: I do think that there are people who are able to connect with and empathize with anyone who is going through something difficult, just naturally. I don’t think it’s a world of effort for everyone. So I think that there is that element of it, where I believe that that’s just who Juan is. But I also feel—and me and Barry spoke a lot about this—Juan is a very dark-skinned Cuban, and the vast majority of Cubans in Miami are fairly fair skinned. I think he was looking to assimilate in some way and he consciously adopted aspects of African American culture because that’s who he most easily resembled. I think he found a degree of comfort in the African American community, but he’s still not African American. So he doesn’t totally fit in with either community in Miami. He doesn’t really have his tribe. So he recognizes what Little is experiencing—in some way, it’s a reflection of his own experience and upbringing, of him not really feeling fully embraced or struggling to identify with who he was. I think it brings them together very quickly. By no means do I think believe Juan was persecuted in the same way that Chiron is—I think that would be a stretch—but I do feel that he definitely connected with how lonely he felt as a young man.

MOONLIGHT COMES OUT IN SELECT THEATERS TOMORROW, OCTOBER 21, 2016. SEASON ONE OF LUKE CAGE IS NOW AVAILABLE ON NETFLIX.