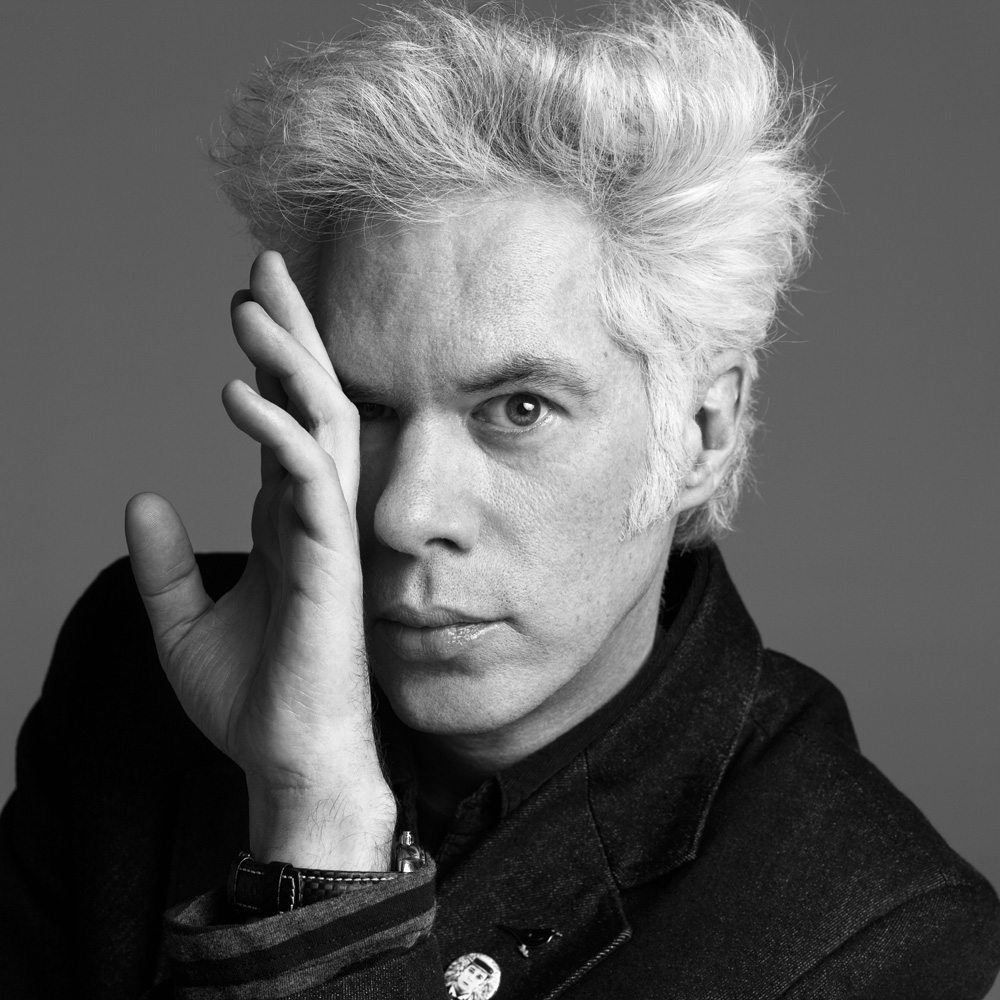

Jim Jarmusch

There must be something about New York City that makes its homegrown filmmakers rebels and mavericks with a natural immunity to the temptations and formulas of Hollywood. Films by John Cassavetes, Martin Scorsese, James Toback, Woody Allen, or Spike Lee don’t need that last title card—the directors’ signatures are in every frame and every cut. New York is the art capital of the world, and maybe that’s what infects our directors with painterliness, poetry, and non-negotiable independence.

Jim Jarmusch is New York’s great new-wave film director in a couple of senses: He was a part of the punk and new-wave generation of musicians and artists, playing in the band The Del-Byzanteens, and conspiring with a group of like-minded bohemians as he turned the new-wave musical energy into the no-wave cinema, a spiritual descendent of the French cinema of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Alain Resnais, and Jean-Pierre Melville.

Jarmusch’s first feature, Permanent Vacation (1980), made with his scholarship money from NYU, was one of the more accomplished films of a burgeoning underground film scene whose directors and actors consisted mostly of lower -Manhattan’s band members and starving artists. It was followed by Stranger Than Paradise (1984), an oddball comedy—made with leftover film donated by Wim Wenders—that starred two of Jim’s downtown musician friends, John Lurie and Richard Edson, as well as Eszter Balint, a member of the Hungarian-refugee Squat Theatre troupe. Stranger won the Caméra d’or at the Cannes Film Festival in 1984 and earned Jarmusch international acclaim. Next was the antic Down by Law (1986), the misadventures of a trio of escaped convicts in Louisiana, featuring Lurie, Tom Waits, and Roberto Benigni, which established Jarmusch as the hipsters’ auteur. His episodic films, which include Mystery Train (1989), Night on Earth (1991), and Coffee and Cigarettes (2003), have brought together eclectic ensemble casts telling interwoven stories in a wry, laconic style marked by blackouts and picaresque but inscrutable plot arcs.

Jarmusch didn’t need to change to please his public, but he changed to please himself. With Dead Man (1995), starring Johnny Depp as a fugitive who travels to the Far Western frontier, the director moved into a new phase—the personal journey, a mode also explored in the brilliant Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999), featuring Forest Whitaker, about a hit man with an inner life. The Limits of Control, which opened May 1, follows a similarly enigmatic character, played by Isaach De Bankolé, who appeared in Night on Earth and Ghost Dog, and who will be recognized by many from his portrayal of the African Prime Minister Motobo on the television series 24. In The Limits of Control, De Bankolé travels through magical landscapes of Spain carrying out a mission mysterious enough to live up to the film’s title, which was borrowed from a William S. Burroughs essay. A wonderful cast including Tilda Swinton, John Hurt, Paz de la Huerta, and Bill Murray conspires to delight with unexpected cryptic comedy and abstract suspense. This extraordinary film should confirm Jarmusch as an artist who ranks with the filmmakers he admires—artists like Melville, John Boorman, Nicholas Ray, and Samuel Fuller.

GLENN O’BRIEN: So The Limits of Control really surprised me. I was even more surprised to learn that you went into production without a script—just notes, right? It seemed so perfectly -plotted out, in a way, almost like a Hitchcock film, I guess because there’s a lot of reverberation. You were playing with repetition.

JIM JARMUSCH: Yeah. We wanted to use variations, so we were building it as we went along. We really had a highly tuned antenna to be open to things. We knew we were building on things that repeat and vary, but we didn’t have all of them—some of them we found along the way. It’s lucky to be able to make a film like that these days, you know?

O’BRIEN: Had you spent a lot of time in Spain?

JARMUSCH: I had off and on. I’d been back there a couple years ago, but it was just kind of reverberating in me. In the press notes, I mentioned these little things that started me off with the story in the first place—one of them being Torres Blancas, this apartment building in Madrid.

O’BRIEN: That’s the building that looks like a flying-saucer convention.

JARMUSCH: Yeah, it’s so wild.

O’BRIEN: Is that from the ’60s?

JARMUSCH: The late ’60s. I always wanted to shoot there. I’d stayed there, like, 20 years ago. So I had that, and the idea of Isaach’s character, in a vague way. I had also always wanted to film in Seville. And then I was shown this picture of this house in the south, outside of Almería. My friends lived on the same street, and they said, “You gotta use this someday.”O’BRIEN: That was the house that Joe Strummer told you about?

JARMUSCH: Yes, it was on the road where Joe’s house was.

O’BRIEN: That’s a sort of fortified compound?

JARMUSCH: It’s actually a tiny little place, but we made it look big. So I’d been just kind of gathering and collecting things. I’d been really interested in chants and sort of trance things, and I tried to incorporate those into the way we actually made the film. And I love William Burroughs’s idea of cutting things up, and, obviously, the surrealists’ ideas of taking mundane things and amplifying details, and Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies—all of those means of how things come together in a not necessarily consciously constructed way. We employed a lot of that.

O’BRIEN: I think the film has a lot in common with poetry in the way that a little object will take on a lot of resonance and kind of collide with something else, and that’ll shift the meaning and create a tangent. I mean, after all the tai chi that Isaach’s character does, then when the flamenco happens and echoes it, that’s just magical, you know?

JARMUSCH: That was another weird coincidence. That dancer, La Truco—her name means “the trick”—when I was talking with her, she said that she teaches a class called Tai Chi Flamenco. She jokingly calls it that because it’s all about slow hand motions. And then I got really obsessed with this one form of flamenco called –peteneras—it’s very slow and tragic, and it’s also kind of taboo among flamenco musicians. They don’t like to play it. There’s a history of bad things happening around it, but it’s slow and it’s not about the feet. It’s more about the hands and the body, and death is usually the subject, or some kind of tragic love. So I asked La Truco to prepare something based on this existing –peteneras song, and she and the musicians created that whole sequence. She worked on it for a couple weeks and just brought that to the film.

O’BRIEN: But that line about going to the cemetery—is that from that song?

JARMUSCH: Yes, it’s from that song. There’s a version by the singer Carmen Linares toward the end of the film where Isaach’s character is driving away. But I think the original goes back to, like, the 14th century.

O’BRIEN: And how did you come across that?

JARMUSCH: Well, when I was researching all this peteneras stuff, I found that one song and got a translation . . . My Spanish isn’t so great.

O’BRIEN: Oh, that’s how I should have started out the interview: “You don’t speak Spanish, do you?” [laughs]

JARMUSCH: Exactly. But I could understand some of the lyrics, and I thought, Ah, I’m going to build that into the whole film. But I didn’t discover it until I was in pre-production in Spain. So that kind of found its way in there. A lot of things just sort of came into it. Like when I was looking for old peteneras—there’s one amazing flamenco record store in Madrid run by this old guy, an expert on the history of flamenco, and I said, “Do you have any really old recordings from the ’20s or anything?” And he was excited that I was interested in peteneras, and he said, “No one asks for that.” And he’s rummaging, showing me all these CDs, and then he goes upstairs and comes back with this CD of wax cylinder recordings. We referred to that performer when we said in the film that the guitar, another object that’s exchanged for information, belonged to this guy Manuel El Sevillano. And then at one point we used a little piece of his actual music, when Isaach De Bankolé’s character is just lying on a bed in Seville and he hears it coming in the window. So a lot of those things kept gathering and were sort of woven in.

O’BRIEN: The locations are magical. Did you do a lot of location scouting?

JARMUSCH: Yeah, we scouted a lot.

O’BRIEN: The views from the train are like a whole other movie. Is that the real view from the train?

JARMUSCH: No. We had to shoot from highways and things like that. And then we had to green-screen those in because there was no way we could shoot on moving trains.

O’BRIEN: Well, it works beautifully. What you see out the window is just incredible.

JARMUSCH: In some ways, the idea of looking at paintings was more inspiring to us than looking at films. I don’t know why. We kind of wanted every shot to accumulate as the film went on, looking at things, mundane things, like you would look at a painting. Or looking at a thing removed from its context, almost. And then I got to put four Spanish painters who I love in the film, in the scenes in the museums that

Isaach’s character visits. And he looks at one of their paintings each time. So I only wanted -Spanish painters.

O’BRIEN: Who painted the nude with no pubic hair?

JARMUSCH: Roberto Fernández Balbuena. He left Spain during the Civil War and went to Mexico, and I’m not sure he ever came back. I think he painted that piece in Mexico, actually. He isn’t so well known as a painter—maybe more so in Spain. But I love that painting.

O’BRIEN: And then the first one is a Picasso?

JARMUSCH: No, it’s by Juan Gris. And then there’s the Balbuena, and the Antonio López García—it’s a cityscape of Madrid. And the last one is by Antoni Tàpies.O’BRIEN: Tàpies’s is the one with the white sheet.

JARMUSCH: Yeah. He started in the late ’40s. He’d been using a lot of found materials in his painting. He was very important in that way.

O’BRIEN: So did you start this film with the title—with that Burroughs essay “The Limits of Control”?

JARMUSCH: I did. I don’t know why. I love the title. The film does not, obviously, relate specifically to the essay—and I love that.

O’BRIEN: No, but the film is about self-control.

JARMUSCH: I thought The Limits of Control could be interpreted in two ways: as the limits of one’s self-control; and as the limits of allowing other people’s control over one’s -consciousness—which I kind of thought was a double meaning that was appropriate. I’ll tell you, though, I thought it was too dry a title, so I thought and thought and tried to come up with another one, but I ended up sticking with it. But it is a little dry. You know, part of me thinks the film is like an action film with no action, or something like that. So I kind of like the title now. The title is better once you’ve seen the film than it is at getting you in to see it. But that’s not my problem.

O’BRIEN: It’s related to action films. In a way, it’s like a tension film. I guess action films have tension, but this one is just sort of winding up and winding up and winding up . . .

JARMUSCH: It’s hard for me to even know what the effect of the film is, having been so close to it and editing it for months. I’m interested in what people say about it or think about it. I hope it’s entertaining. I didn’t want to make something that was stiff. I want it to be a trip you take—and a kind of trance. And I didn’t want to require a lot of difficult, cerebral things from the audience. I wanted it to be entertaining but not really story-centric somehow.

O’BRIEN: I think it is a trip. It’s just so intensely focused in the beginning that you’re really with Issach’s character. You can project so much on him because of his silence and his intensity. His presence just carries you forward. And then when it gets really intense, there’s always a laugh. It’s like, “You don’t speak Spanish, do you?” Those little gags are the encounters that break the ice and bring you back to the starting point . . .

JARMUSCH: I like the way he has to listen to these contacts talking on and on about whatever subject they’re interested in and then eventually he puts down the matches and is like, “Okay, enough. Let’s get to business”—without any dialogue, really. But he’s open. He’s listening. He’s interested. He’s absorbing things all the time.

O’BRIEN: Maybe I’m thick, but I couldn’t figure out if he was a criminal or a spy.

JARMUSCH: I wouldn’t even know how to answer that. He’s obviously traveling under the authorities’ radar, and therefore he appears to be a criminal of some kind. But I don’t really know.

O’BRIEN: If he’s a criminal, he’s an honorable one, like Jef Costello [Alain Delon] in Le Samouraï [1967] or Bob Montagné [Roger Duchesne] in Bob le Flambeur [1956] . . .

JARMUSCH: I hope so, yeah. There’s a big Melville inspiration. I like how quiet and how focused he is. But the whole film is kind of metaphoric so that even what happens in the end, which defines the purpose of this mission, is not very important or interesting to me, in a way. It’s more of a culmination of this sort of metaphorical process. I was trying to play with human expression, artistic expression, or imagination, or science versus controls over the way we perceive things and what we consider reality.

O’BRIEN: There’s a poster depicting the Tilda Swinton character that looks like a movie poster. What does it say?

JARMUSCH: It’s a film poster from an imaginary old film—in Spanish, the film’s title means “a lonely place.” One of my favorite films is In a Lonely Place [1950], a Nick Ray film with Humphrey Bogart. The person in the poster is either Tilda or someone Tilda has imitated. That’s open to interpretation because she’s sort of the angel of cinema in the film, the way she talks about cinema. The contacts are sort of . . . I wouldn’t say cartoonlike, but some of them are drawn in a broader way than the central character. How Tilda looks is about artifice and fabrication, in a way. And films are all artifice, so she’s sort of celebrating that.

O’BRIEN: The first time Tilda appears, she looks a bit like Candy Darling.

JARMUSCH: Oh, that’s interesting.

O’BRIEN: I guess it’s the sunglasses and the hairdo, but there’s almost something like drag in it. There’s plenty of artifice there.

JARMUSCH: Yeah. I love to make Tilda look different than her normal self.

O’BRIEN: Where did the tai chi thing come from? Is that something that Isaach does?

JARMUSCH: He does now. He actually trained to do it for the film. Funny you should ask—I just ran into him on the way here. Both of us have a close friend, Shifu Shi Yan Ming, from the USA Shaolin Temple. He’s a Shaolin master and sort of my philosophical teacher. So Isaach learned some basic movements from him, as have I. But it entered the film because I wanted this character to collect himself, to be very centric. And it’s also very visually beautiful. Shifu hasn’t seen it yet, so I hope he doesn’t say, [in Asian accent] “Ah, right hand down, out of place—no.” Because I watched really carefully, and we brought little videos with us of Isaach performing these moving meditations with Shifu, so he was there when they filmed it. I tried to watch and make sure we did everything right—a few times I did another take because it wasn’t quite perfect, and I didn’t want Shifu to see that.O’BRIEN: I mean, I don’t know much about it, but he was really very fluid.

JARMUSCH: Yeah, it’s closer to qigong, which is more flowing, but adding in a bit of tension that is from tai chi—like imagined resistance. So you can do some of these very flowing movements like qigong. Or with tai chi, which is a little more muscular, you will put some moment of tension there, you know?

O’BRIEN: What’s the thing where he kind of goes berserk at the end, where he does the violent movements?

JARMUSCH: That’s something that Shifu always does when he does slow, meditative movements. At the end, he shakes it all out. It’s something we’ve seen Shifu do. So we just imitated him doing that. But he is amazing, Shifu Shi Yan Ming.

O’BRIEN: How did you first encounter him?

JARMUSCH: Through the Wu-Tang Clan when I was doing Ghost Dog. RZA is the godfather of Shifu’s son, who is now 9. Shifu was in Ghost Dog, actually, appearing as an old man carrying groceries—somebody attacks him, and he does, like, two moves, and the guy runs away. I used to go to the temple a lot, and I became a kind of adviser. Wesley Snipes is also a member of the temple. So I just got hooked in, and now Shifu is like my philosophical navigator.

O’BRIEN: The cinematography is amazing. I’ve seen some of Christopher Doyle’s other films, like 2046 [2004], which is so beautiful. How did you get together?

JARMUSCH: We’ve known each other a long time—at least 10 years, maybe more. And we’ve hung out in all these places and always wanted to work together. A few years ago, we did a music video using these very primitive digital movie cameras that were for kids’ along with some Super 8, and then we just kept talking. I was going to make a different film before this one, and that fell through. But Chris was going to shoot it, and he kind of put off some jobs waiting for that one that didn’t happen. And then he put off some stuff for this, just waiting to do something together. So he gave a lot to me. I was really happy to get his mind in there. This film is a bit different from a lot of his other stuff because he likes to shoot handheld a lot—he likes moving cameras. We have a lot of moving cameras in this film, but in an elegant, tracking kind of way. It was great to get his visual sense into it. I was a bit less on him than I usually am with DPs. I’m very particular about the framing of everything—and I was in this case too. But I would let Chris set up first and show me and talk about it, and then I’d say, “Well, where would you place the camera for the first shot?” You know, “I want these four shots for the scene.” I’d just let him think and find something and, man, 90 percent of the time, that was it. Often the ideas were similar to what I might’ve done, but often they weren’t.

O’BRIEN: Yeah.

JARMUSCH: For him, each shot in the film is important, and he doesn’t think very much about editing them together. Sometimes I’d have to adjust things a bit to make sure they would cut. But I love the idea that he’s interested in what we’re doing right now, each moment. He’s very fast, and he’s funny, because we’d do a shot and it would be a good take for the camera, but I’d want to do it again for acting, and he’d be like, “Why? We have one take. What’s wrong with that?” He’s from the Chinese school where, if you get one good take, then you just move ahead . . . It was quite interesting, his approach.

O’BRIEN: How did you get away with making a film without a script?

JARMUSCH: Well, I gave a 25-page story with no dialogue to Focus Features, and I talked to them about how I wanted to proceed. And the story contains pretty much the scenes that are in the film. So the structure was visible from my story. And I explained to them, “Look, I don’t want to write a traditional script because I want to find things as I go. I want to keep incorporating things, and the film has to be made that way.” And they said, “Okay, if that’s your process. We like the story, we know Chris’s work, and we know your work.” They knew who I had cast, so they didn’t interfere or even give me any suggestions—nothing. They were really great to work with. I was lucky. I don’t know if I could pull that off again.

O’BRIEN: How did you instruct the cast as to what you wanted out of them?

JARMUSCH: Well, I got to rehearse very briefly with them. Usually they’d come in, and then I’d have to go over their wardrobe, and I’d meet with them and either give them something I wrote, or I’d discuss it with them and then go back to my hotel and write it for the next morning. So I didn’t have a lot of time, but some of the actors, like Tilda and John Hurt and Bill Murray and Youki Kudoh, I’d worked with before, and so I had a sense of how to work with them. For example, when I shot the scene with Tilda, I’d written the dialogue the night before, and I hated it. I thought the writing was bad. So I said, “Look, we’ve got to come back tomorrow. We’re going to shoot this scene again. I’m going to go write it over again.” So I did, and then the next day I really liked it, and Tilda liked it. I spoke with her in the morning. We all talked as much as we could, given our short time together. The actors came in, like, the day before I was going to shoot, and they didn’t even know their wardrobes. They didn’t even have their script. They didn’t even know what their characters were, really. [laughs] I mean, I’d just talked to them on the phone and given them ideas about the characters . . .

O’BRIEN: I loved Isaach’s wardrobe. When he changes his suit, you know it’s Act II.

JARMUSCH: Yeah, exactly. It’s color-coded acts, in a way. I liked the design of the suit. We kind of designed it ourselves. I approached Tom Ford to see if he would maybe do suits for the film, because I like that tight kind of thing. But I approached him so late in the game that he said, “Oh, man, I got a show coming up. I would love to do this, but I can’t pull it off.” So then we just kind of worked from drawings and discussing the suit fits and having Isaach there. The designer, Bina Daigeler, worked with a Spanish tailor, an older guy. So we kept adjusting it. I’d come in and say, “No, the jacket is a half-inch too short.” And it was hard to find those fabrics. We kept hunting and hunting, and found the fabrics we liked, and photographed them in different lights. We finally got those three suits made just in time.

O’BRIEN: I love the iridescent sharkskin.

JARMUSCH: I love that look. I wanted him to look kind of like a gangster from an ’80s crime film in some way. He’s more of a mental, philosophical gangster. I’d seen Isaach, like, 10 years ago in a mustard-colored iridescent suit that was very fitted. When I was writing the film, I wrote that he wears different colored iridescent suits.O’BRIEN: What did you tell Isaach about his character? Or not tell him?

JARMUSCH: We talked a lot about how quiet he was, about his philosophy that goes with tai chi. We talked about some books that he did not read, these books by Richard Stark, a.k.a. Donald Westlake. In the Stark books, there is this character Parker, who is a criminal, but he’s very focused. That’s where the thing about no sex came from, because in the Parker books, the character is not distracted by women. When he’s on a job, he’s on a course. We talked about how this character had to indicate things with the tiniest amount of facial expressions. We talked about how he walked . . . things like that.

O’BRIEN: I looked at my watch, and it’s an hour into the film when he smiles. And it’s a little smile, but it really seems big because he’s been so deadpan.

JARMUSCH: Isaach can do something with one eyebrow or just narrowing his eyes sometimes. He’s amazing. For years I’ve loved how Isaach’s face changes if you change it slightly. I’ve seen him with an Afro. I’ve seen him with a shaved head. I’ve seen him with short hair, nappy hair, semi-little dreads. I’ve seen him with facial hair and without. I mean, he always looks like a different guy. Some years ago, he gave me two passport photos that he had taken a day apart, and in one he had a beard, and in one he didn’t. You would think, Are these guys cousins? They looked related, but you wouldn’t think it was the same guy. He’s got a remarkable face, Isaach, and his spirit comes through.

O’BRIEN: I like in the press notes how you say that the two cups of coffee came from . . .

JARMUSCH: A real incident, yeah. Isaach is very particular. I said, “I’m going to keep that incident in there, and I’m going to use the coffee cups throughout as a code.” He liked that, so that’s why the only time his character gets really emotional is when the guy doesn’t give him the right coffee.

O’BRIEN: I like that every time he’s in a café sitting and waiting for a mysterious contact, you go to a shot of the birds. It’s almost like the classical idea of augury—you know, how the priests would tell the future by the way the birds flew around and nested on a temple. It was a big part of divination in ancient Greece and Rome.

JARMUSCH: Oh, really? I didn’t know that.

O’BRIEN: You didn’t know that? It fits right in.

JARMUSCH: Wow. Like a flying version of tea leaves. Well, I didn’t intend that, but I’m sure there are a lot things in the film that people will find that I wasn’t conscious of . . . I hope.

O’BRIEN: I think it comes out of your film language. It works like poetry and painting.

JARMUSCH: When I wrote the little minimal story, I would say that he goes to the museum, he finds a specific painting, he studies it, he leaves, and then after that, he looks at the nude girl as though looking at a painting. He was on the train; he looks out the window as though looking at a painting. It was a thing that kept repeating. So it was kind of a guide, to have him look at many things really like you would look at a painting. I was watching some show about Greek and Roman art in museums and how it got moved around through colonialism and was stolen and smuggled. And I was thinking that it’s interesting because only Western colonial culture has that idea of museums, where things are removed from their context. So I was thinking, Well, museums are really a result of our religion being money, and that colonialism was a great pillaging of the world. I’d never thought about that before, but it really struck me that museums removing things from their context comes out of a colonialist overview.

O’BRIEN: Ishmael Reed, in his novel Mumbo Jumbo, talks about the museum as the center of art detention. The colonialists took all these very powerful magical objects—cultural keys—and took them away from Africa and elsewhere, and, in a sense, emasculated their religious practices or their spiritual identities.

JARMUSCH: When I was preparing Dead Man, I was in contact with a lot of first-nation people up in the Pacific Northwest, these Kwakiutl and Haida people. There’s a huge museum in Vancouver that has some of the most beautiful artifacts of their cultures, and they call it The Warehouse, and they’re really indignant, like, “Yeah, well, the most beautiful shit’s in The Warehouse. They’ve got it in their Warehouse.”

Glenn O’Brien is Interview’s editorial director.