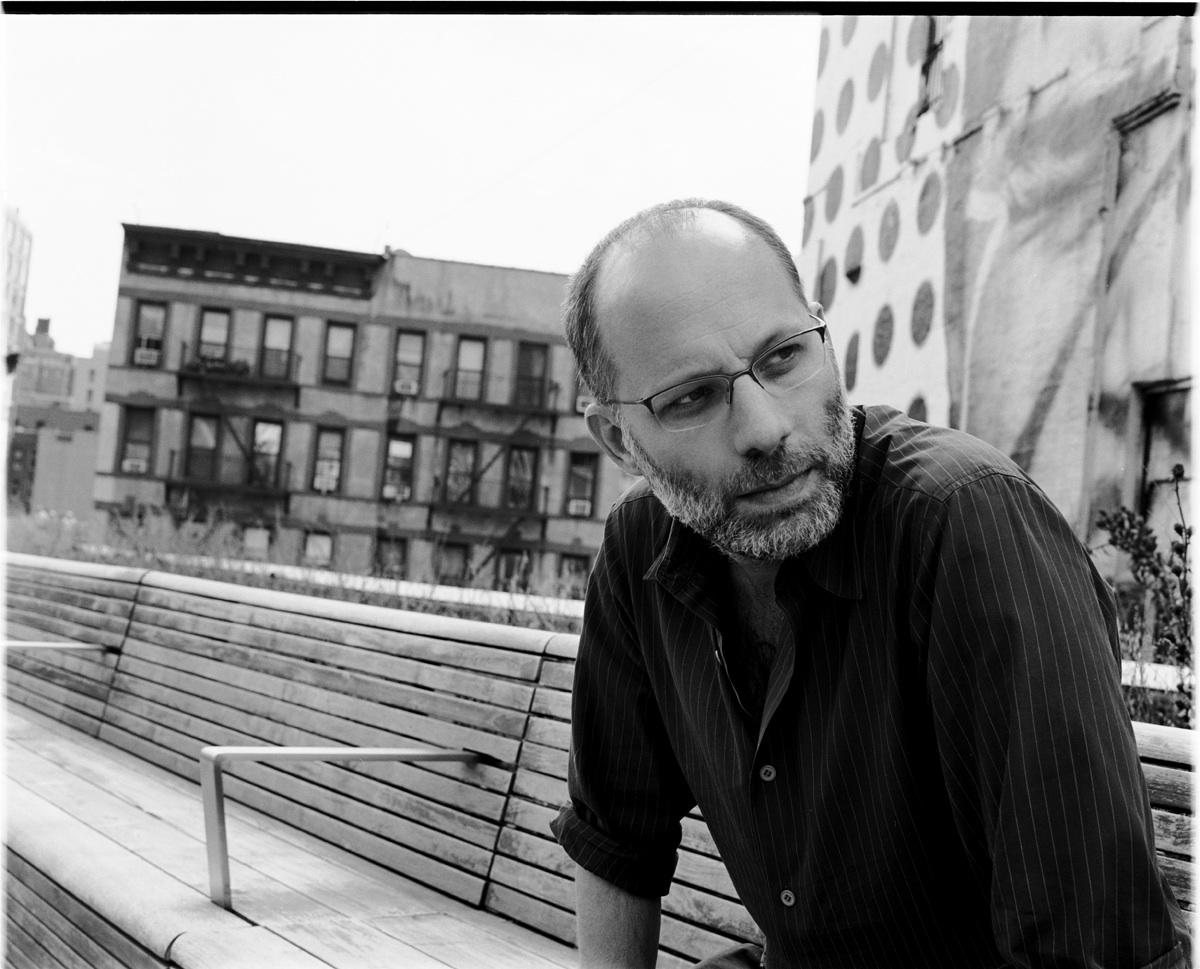

Ira Sachs: Everything is Illuminated

When the two characters at the center of Ira Sachs’s quiet, stirring new film, Keep the Lights On, first meet, their relationship isn’t supposed to last beyond a few hours. “I have a girlfriend, so don’t get your hopes up,” the angelic Paul (Zachary Booth), a closeted lawyer, tells Erik (Thure Lindhart), the Danish documentary filmmaker he’s invited to his apartment for a quick, anonymous hookup after connecting on a gay chat line.

But there’s something deeper between Paul and Erik, and the two quickly fall in with one another, starting a relationship that ebbs and flows over the space of nearly a decade—the film spans from 1997 to 2006. The pair celebrates routine domestic triumphs and battles more singular demons—most notably, Paul’s worsening crack addiction, which haunts them both. The film is based in large part on Sachs’ own long-term relationship with his ex-partner, Bill Clegg, who has also explored their time together in his own creative endeavor, a memoir titled The Portrait of the Addict as a Young Man.

The Erik character, like Sachs himself, is deeply interested in film as a medium for telling stories that would otherwise be silenced. He works within the film on a documentary about the artist Avery Willard, a gay activist who photographed male nudes in the pre-Stonewall era and went on to produce both a newspaper called Gay Scene and a gay pornography production company later in life. In a tidy bit of meta-karma, Erik’s documentary wins the LGBT-centric Teddy Award at the Berlin Film Festival in the film—which Keep the Lights On would go on to win this year.

We caught up with Sachs to discuss sex on screen, New York as a character, and the fate of that fictional documentary.

ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS: It’s hard to tell, when you’re in the middle of it, when a functional relationship gives way to being a dysfunctional one. Do you think it’s possible in hindsight to see what that exact moment is?

IRA SACHS: If, in the first month of a relationship, the person you are going out with pulls out a crack pipe, leave. [laughs] Leave. Walk out right then.

SYMONDS: That was actually my next question. Do you think Eric and Paul are doomed from the first time Paul lights up the pipe?

SACHS: I think the story, in a lot of ways, is about two men who don’t like themselves very much, so they attach to each other as a way of getting by. In a lot of ways, I think it’s a film about obsession—even more than dysfunction. An obsession, in a way, is a certain kind of compulsive attachment to some person, place, or thing that attempts to shut out all the other questions that the individual feels about themselves—so in a lot of ways, I feel this is a coming-of-age film. A coming-of-middle-age film. [laughs]

SYMONDS: [laughs] I don’t know if I’d go so far as middle age—I mean, they’re still pretty young at the end of this film.

SACHS: I’m 46, so I identify in the middle. The film is very autobiographically inspired, and the events that the film depicts—particularly the explosion of their relationship at the end of the story—when those were [happening] in my own life, they were the necessary moment of eruption that allowed me to do things differently afterwards. In a lot of ways, you could say the film itself is the result of the relationship, meaning: it’s a very open film, it’s a very honest, it’s very a shameless film about a couple who is doomed by secrets, shame, and self-destruction.

SYMONDS: You mentioned that it’s a very autobiographical film—and, uniquely, it’s a story that has already been explored by the other half of what was once the pair of you. When two creative people break up, how do you decide who gets the intellectual property of the shared memories?

SACHS: [laughs]

SYMONDS: Do you consider your work to be in any way a response to Bill’s work?

SACHS: I make films that are very personal, and I always have. It’s kind of the only thing that I think I have to offer as a filmmaker: the intimacy I’ve had with experience in a particular world, so the film comes from things I’ve seen and things I’ve felt. It gets transformed by the process. I don’t think I’d ever start making a film until I had both the intimacy with the subject and the distance to make it live in a certain way. The film tells a story about a character called Eric and a character named Paul and their world in New York—these actors, these locations, these spaces, this story, which is the story of Keep The Lights On.

SYMONDS: You talk about New York a lot, and you did what I thought was a good job of capturing the neighborhoods that the characters inhabit shifting throughout time. Could you speak a little bit about your process of getting locations, and how much the geography of your real life overlapped with the geography of the film?

SACHS: Yeah, we were inspired by a wide range of films in making this movie, including Goodfellas and Annie Hall, and I think both those films depict the city changing over time. What I loved about Goodfellas is that it’s a film about bad behavior—but told with great energy and without judgment—but it doesn’t actually shy away from the consequences of that behavior in the characters’ lives, which I think is similar in Keep the Lights On.

But what I found is that if we use locations that come with their own history, we get a certain depth, and New York becomes vivid in the film. So nearly all the locations are in spaces that are nearly 100 years old. So Alfara’s was a restaurant in the West Village that was around in the mid-’20s, De Robertis in the East Village is a hundred-year-old pastry shop, Julius is the oldest gay bar in New York City. As a filmmaker, you realize that places have character based on their history as much as a face does or an actor does. I tried to bring that into the film as much as possible.

SYMONDS: I was struck by how Paul and Eric’s relationship is bookended by two shots of Paul opening an apartment door for Eric. How did you decide to structure the film?

SACHS: To me, that was very important, those doors, letting someone into these apartments. In real life, those apartments are on the same block, on 15th Street between 7th and 8th avenues, so I found it personally very moving that there was a day that I left one apartment, I moved into another one, and they were ten years apart.

When I started working on the film, I utilized journals and diaries, and emails and letters. In some ways, the film is structured like reading someone’s diary, and you can see there’s a series of dramatic high points in these characters’ lives, with ellipses between those moments—which is sort of how life moves, both in diaries but also in memory. We don’t tend to remember the linear narrative; we remember the things that pop.

SYMONDS: I wanted to ask about the decisions that you made as a director regarding when to show events and when to pull back, particularly when it comes to the depictions of sex and drugs in the movie.

SACHS: I think I wanted to show a film in which the sexual behavior was included within everyday life, instead of separated out from it. That’s a kind of unusual texture of the movie, and I benefited by working with a cinematographer who has no fear of sex.

SYMONDS: He’s European.

SACHS: He’s European! No, you say it as a joke, but actually, I surrounded myself with Europeans, because we’re very American here. I have a Brazilian cowriter, I have a Brazilian editor, I have a Danish lead actor, I have a Greek cinematographer. I think that’s why the film played very well in Berlin, because we are still at a very puritanical state. And independent film in general is more and more connected to commercial cinema, and commercial cinema is frightened of sex in America.

SYMONDS: I’m curious about how the scene at the Berlin Film Festival within the movie played at the actual Berlin Film Festival—did people laugh?

SACHS: Yes, what was very rewarding is that I was asked where in Berlin we shot that scene, and we actually shot it on Irving Place. Every fictional film is a form of documentary in a lot of ways, and what you’re trying to do is create and recreate worlds with as much texture and authenticity as possible. For example, in that scene, we got a lot of German extras, and we got a lot of people that work in the film business, which are the kind of people you’d find at a party in Berlin. So there was a kind of authenticity to that scene that I think played well in Berlin, and then I ended up winning the Teddy Award.

SYMONDS: Right, which is great.

SACHS: Yeah it was really funny, truthfully, and it was also really fun. It was funny because I was finally on stage receiving an award like in a scene that Eric receives an award based on playing a role of someone based on me who’d received an award a year before at a different film festival.

SYMONDS: Right, there’s like a hall of mirrors. Can we talk a little bit about the film within the film? I found myself wanting to see the documentary.

SACHS: Well, you can, we finished it.

SYMONDS: Oh, you did?

SACHS: When I was working on the script my husband, Boris Torres—who actually is the painter who did the opening paintings in the movie; the character of Igor is based on Boris.

SYMONDS: They’re beautiful.

SACHS: Thank you. And we’re very connected to each other in terms of our work—his work is very sexual and very open and has a lot of humor in it, and I’ve been very inspired by it. He said to me, “I think the character should make something that you would be interested in,” and I happened to be going that day to the New York Public Library to do some research on these lost films of Avery Willard, which I had heard about from Anthony Hegarty.

I run a film series called Queer/Art/Film, and within that series we do some restoration. So I was heading to look up Avery Willard’s films, and I didn’t know what my character, what film he was going to make—and I thought, well, he’s going to make a film about this person that I’m curious about.

So we actually started making the film during pre-production and did a lot of interviews, which then the actors later did again with many of our subjects, including James Bidgood—who’s the guy who talks about Nixon in the film and who made himself an incredible movie called Pink Narcissus. After we were done, my intern became the director of that film, and he finished it, and it’s a wonderful film about a lost history. And for me, that’s what our film is about—it’s a lost history of relationships and life now in New York that I felt like as a filmmaker I could create, I could bring to existence, I could make visible. Which I think is a lot of what filmmaking is about, is making history visible.

SYMONDS: Are you prepared to talk about what you’re working on next?

SACHS: Yes, yes. I’ve made four films about the destructive nature of relationships, of secrets and lies, and I think I’m not longer interested in that subject—which is a wonderful relief. So I’m making a movie about a couple who’s been together 38 years in New York City, two men, they decide to get married. And following the wedding, one of them is a choir director at a Catholic school, and he gets fired, and the film is about how they end up losing their apartment and have to be cared for by their friends and family and how as a couple they try to stay together. But they try to stay together because they love each other, not because they’re obsessed with each other. It’s a film about the possibility of love to blossom over time.

KEEP THE LIGHTS ON IS OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE TODAY.