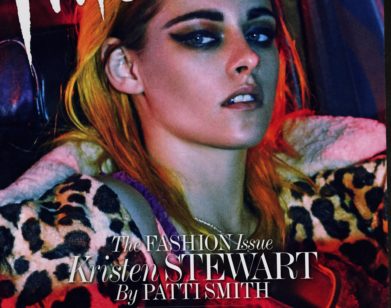

Charlize Theron and Kristen Stewart

Interestingly enough, there is one way in which Charlize Theron has less experience than Kristen Stewart. With the Twilight experience behind her—Twilight (2008), New Moon (2009), Eclipse (2010), Breaking Dawn-Part 1 (2011), and this year’s Breaking Dawn-Part 2—the 22-year-old Stewart has been at the eye of the major-movie-phenomenon hurricane more times than Theron. For the most part, Theron, 36, has contented herself with pursuing projects that ask questions about the way that women are defined, and the ways in which they often deal with oppression in those roles. Those parts have ranged from her most recent role in Jason Reitman’s Young Adult to a spate of dynamic biopics that includes the risky reset of her career in Patty Jenkins’s Monster (2003), which earned her an Oscar for best actress, and Niki Caro’s North Country (2005), which earned her a nomination, as well as her turn as Britt Ekland in the 2004 HBO film The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, for which she was nominated for an Emmy for best supporting actress. Even Theron’s lead in Karyn Kusama’s 2005 action film Aeon Flux involved playing a character that exists simultaneously as a character as well as a commentary on women in genre films.

Stewart’s interest in serious acting gives her something in common with Theron—and, like Theron, some of her most provocative work has come through working with women. For Theron it was Monster, by writer-director Jenkins, that marked the turning point. But Stewart’s history of teaming with women spans her entire career, and includes her performance at the age of 10 in her first film, Rose Troche’s The Safety of Objects (2001), as well as costarring with Jodie Foster (who is clearly a role model) in David Fincher’s Panic Room (2002), being cast in the first Twilight film, directed by Catherine Hardwicke, and her remarkable turn as trailblazing rocker Joan Jett in Floria Sigismondi’s girl-epic indie film The Runaways (2010). Stewart and Jett got to know one another during the filming of The Runaways, and, like Foster, Jett’s influence on Stewart is palpable. (Stewart was amused when I told her a story about Paul Schrader’s 1987 film Light of Day, in which Jett co-starred with Michael J. Fox; the movie’s original title was Born in the USA, which Bruce Springsteen liked so much that he asked Schrader if he could use it, and wrote the director a song as recompense.)

The upcoming Snow White and the Huntsman, an armor-plated retelling of the classic fairy tale interpreted by first-time feature director Rupert Sanders, transforms the apple-blossom character of Snow White into something out of a Robert E. Howard pulp novel, and represents a departure for both Theron and Stewart. Theron says that she was intrigued by the psychological demands of the material in playing the complicated Queen Ravenna, and Stewart’s performance as Snow White, the fairest of them all, in her first action-heroine role, kept her literally in constant motion. But both women enjoy being challenged—by work and in conversation. I’m pleased to say that the reward with each—I spoke with them separately; in person with Stewart, and over the phone with Theron—is that they are quick to laugh, which makes talking with them even more pleasant.

Click here to jump to Charlize Theron.

———

ELVIS MITCHELL: In looking at the films you’ve done, one thing that strikes me is that you’ve worked with a lot of women—and a lot of female directors.

KRISTEN STEWART: Quite a few, yeah, which is rare. It’s hard to generalize about that subject because the women I’ve worked with have all been so different. But if there’s one consistency, it might be that you do have to handle yourself differently on a set. Women can be more emotional—at least they sometimes show it more.

MITCHELL: In what way?

STEWART: You know, with the film industry crews, there’s an odd mix between a very technical and a very artistic approach to the work, and sometimes as a woman you have to be a little bit careful about how things come out because people don’t really want to listen if it’s in a certain emotional tone or too strong.

MITCHELL: If it’s too directly emotional?

STEWART: Yeah—if it’s addressing a direct emotion. I mean, it’s this weird thing that I always feel like I have to gauge in myself, like, “Don’t come on too strong because you won’t get your way.” It’s like you have to be very tactful in how you get things across. But it’s mostly in the group discussions that anything like that comes up. In personal conversations between director and actor, the male directors that I’ve worked with are just as emotional. Maybe it’s because I had to start having very intimate conversations with adult men at a very young age in order to get the work, but I’m really comfortable with dudes. I mean, we push boundaries in this business in terms of getting to know people. There are things that directors know about me that people shouldn’t know. But everyone’s really different. I’ve worked with women who I’ve never wanted to tell anything about myself to, and I’ve worked with guys who have been pouring wells of emotion. So emotional availability is not a gender-specific thing.

MITCHELL: When was the first time you remember working with a woman who you instantly connected with?

STEWART: Well, Jodie [Foster, who Stewart worked with on David Fincher’s Panic Room, 2002]. But actually, the first person who hired me for a movie was a woman: Rose Troche, who directed The Safety of Objects [2001].

MITCHELL: You were a kid when you did that movie.

STEWART: Yeah, I was 10. It was the first part I ever got. I was almost done auditioning at that point. I wasn’t getting anything and I figured that it just wasn’t worth it. But that was the first time I had an audition where suddenly I felt something. I remember looking up, and there was a camera, because I was being filmed, and I looked over at Rose, and I knew instantly that I had gotten the part without her even saying anything.

MITCHELL: Just from the way she was looking at you?

I have this weird aversion to people going, ‘It’s a nice, strong female movie. It’s really strong.’ It’s almost like you’re kind of discrediting the strength.Kristen Stewart

STEWART: Yeah, totally. And then we sat down and talked about the part, and how it was an odd part for a young person to play, to be confused with a boy—Tim Olyphant’s character sees something in my character that reminds him of his brother who died. But Rose was really sensitive about it, and I was like, “No, it’s cool. I totally look like a boy! It totally works for me!” She was like, “Great. I’m not gonna have to be delicate with this one.” It’s interesting now that I’ve worked with kids, too. With kids, it’s like you can see something that they’re not aware of yet, even though they’ve got it in spades. I can totally see how all those women kind of went, “Oh, this kid likes it. She’s not just going through the numbers.” But I wouldn’t have kept doing things the way that I do them if I had just been pretending on Safety of Objects. I’m not a performer. Especially when I was younger, I was not the type of kid to put on a show. Acting was really about just wanting to have certain experiences.

MITCHELL: Did you feel up until that point that people treated you like a kid and not somebody who really wanted to be there?

STEWART: Yeah. And rightfully so. But it’s not like I was upset with the way I was being treated. I just wanted so badly to be involved.

MITCHELL: The Safety of Objects is a pretty female-oriented film, too, which covers women’s stories and their points of view.

STEWART: It is. It’s weird, though, talking about the whole woman thing—especially now with Snow White, Charlize, and everything. I have this weird aversion to people going, “It’s a nice, strong female movie. It’s really strong. Are you trying to do stuff like that?” I get asked that constantly.

MITCHELL: Do you?

STEWART: Yeah. Everyone goes, “All the roles you choose—they’ve all got some sort of gusto.” And, really, it’s by chance. It’s almost like you’re kind of discrediting the strength by saying, “Strong girl, strong girl.” It’s like, “She’s just a strong person.” Yeah, the whole woman thing . . . I don’t really know how to address it. These characters are all just people.

MITCHELL: So what did you see in Snow White and how this character lived on the page for you that made you want to try to bring those qualities to the screen?

STEWART: There’s so much that Snow White has been deprived of in terms of having the proper time to really develop and hone who she is. She’s put in jail at the beginning of her life, so she’s a stunted person. She has a really idealized concept of what the world is, and how people should live, and how wonderful things all can be, and there is this debilitating isolation that she feels because she has been locked away in a little cell for seven years. And I can kind of relate to that. There is something… It’s not the reason that I wanted to do the movie, but the fans and people who loved Twilight, they do put you on this sort of different plane where you’re not real.

MITCHELL: You become a kind of ideal.

STEWART: Exactly. It’s like you don’t exist. And Snow White doesn’t exist. That’s how she starts out in the story—she’s just a false hope. She also doesn’t believe in destiny. It’s like, how could she defeat something that all of these people’s own hearts and own homes were broken by? How could that be possible for one girl? And it’s just about heart. I wanted to join her cause. The reason I wanted to do the movie was because I just wanted to go, “I know it hurts, but this is your burden, and I’m behind you.” We also don’t have a purely evil queen. It’s not like Ravenna completely lacks humanity. It’s just that she’s not able to be fully human. So what I also loved about it was that we didn’t have two polar opposites where good defeated evil because it’s better. It’s just that in hard times, you have to have strength of heart. You can’t be a selfish bastard. Some people are gonna get hurt, but it’s about making sure that the whole prospers.

MITCHELL: So it’s your chance to be Joan of Arc.

STEWART: [laughs] She is absolutely Joan of Arc.

MITCHELL: How do you embody someone who has that kind of life force?

STEWART: The tricky thing is that you can’t have Snow White’s effect on people. I can’t have this supernatural light that sort of instantly affects those around me. There were things that I needed to believe, even though it was hard at times. But I did because the fantasy part of it was written well. You know how you meet people in life sometimes where you go, “Wow, you’ve got this energy . . .” This is just sort of a heightened version of that.

MITCHELL: You see people in movies like that all the time with that kind of quality where they’re something bigger than every- body else around them. Did you draw on the movies as a sort of antecedent for that? Or did you try to draw on a real-life version of someone you knew who had that kind of quality?

STEWART: I didn’t think of a specific person… I mean, she’s very maternal. I feel like a lot of mothers have the effect that Snow White has on people.

MITCHELL: Your own mom to some extent?

STEWART: Yeah, definitely—at times. My mom is a tough lady. [both laugh] But with me, she’s definitely maternal. I think that anyone who was involved in the project probably had the same feeling about the story that the director Rupert [Sanders] and I did, which is that if you believe in it enough, you start to be able to convince yourself of things that could never be true. But it’s the same struggle for Snow White as well because she doesn’t really believe in her own effect on people.

MITCHELL: What were your conversations like with Rupert, who is basically building this enormous city from scratch? That’s a lot of trust to place in someone who literally hasn’t done a film like this before.

STEWART: Well, one great thing that Rupert did as a director was put me in an environment that felt so real that all I had to do was live there. Nothing ever felt silly—right down to the troll in front of me. With some things in a fantasy movie, where you’re in front of green screens and stuff, you have to have a pretty trustful imagination. You can’t be insecure or have that thing kick in that makes you go, “This is stupid.” And to Rupert’s credit, I very rarely went, “Really? What are we doing here?” You know, Snow White doesn’t say a lot, and the movie is so hectic with things happening so fast that who she is wasn’t really defined in a line or a scene. It was something that we needed to find in between the lines—and that was scary and hard up until the last day.

MITCHELL: Was part of it made easier by the fact that it was such a physically demanding film. Did that help you at all?

STEWART: Yes, I think it really helped define the character in a lot of ways. I liked not having to fake it, because in the original drafts of the script, Snow White kind of became this ninja person overnight who was just able to, like, own this six-foot armored man, which would never happen. We wanted everything to be, like, “Oh, fuck. She barely made it through.” Somebody my size couldn’t go into a man war and come out alive with only a sword. That just would never happen.

MITCHELL: [laughs] I’ve never heard it called “man war” before.

STEWART: A man war.

MITCHELL: I think that should be the next movie . . . [Stewart laughs] Tell me about Charlize.

STEWART: She is unlike anyone I’ve ever encountered. She is one of those people who walks into a room and everyone knows it.

MITCHELL: She’s a movie star.

STEWART: She’s a fucking movie star. It’s funny, too, because she always says, “I’m not really a performer.” But I’m like, “Yeah, not at all.” [laughs] She’s an actor and a performer.

MITCHELL: It’s funny you mentioned that because she said the same thing to me.

STEWART: Well, I think that’s the actor in her. I think she loves being an actor and is so true to it that she might not acknowledge everything she’s capable of. But she’s so real all the time. She’s not the type who is easily rocked on a set. She’s very much in control of her thing.

MITCHELL: How much of that is like you?

STEWART: It depends. Some things come really easy, and they just explode out of you, and then as soon as they say cut, it’s easy to take a breath and joke around. But there are certain things where I just need more of a pre-amble—just to convince myself of what I’m doing. But Charlize and I do kind of have similar approaches. We only had a few days together, but we both are absolutely willing to hurt ourselves to do what it takes to get the right feeling, and not all actors are like that. Most actors like to be really comfy.

MITCHELL: Is that part of making it real for yourself—to have that discomfort?

STEWART: Yeah, definitely.

MITCHELL: With On the Road, you’re playing a real person in LuAnne Henderson [the inspiration for Marylou, Stewart’s character], but at least you’ve got the filter of Jack Kerouac’s interpretation, so you’re playing somebody who is based on his version of her.

STEWART: But we were privy to so much more. Walter Salles’s version of On the Road is really a mix between On the Road the novel and the scroll version of the text that Kerouac wrote, which is different, and the history of it all. We used a lot of what happened outside of the pages of On the Road, and because of that, I think the female characters changed a lot—they began to function as something more than playthings. It was so much easier to play the part compared to just reading the book and going, “Wow! This girl just doesn’t fucking care. She’s just kind of a sociopath.”

MITCHELL: Because you read the book, and the main thing from the book is “Who can I use? And how can I use this person right in front of me now?”

STEWART: Completely. LuAnne was so aware of that. She’s tough. She’s defensive sometimes, but she’s really sparky. We listened to hours of tape of her, and hearing her perspective did make it easier.

MITCHELL: There is a real hunger in so many of these young women that you’ve played—this appetite for something.

STEWART: That is totally true. I do think, though, that there is a niche that people are trying to fill right now because of the female audience. Females want other females to be really strong, so there are a whole lot of scripts that are basically just male parts renamed as a girl. It’s like, “That is not a woman. That is not the strength of a woman. That is just a woman trying to imitate a man.”

MITCHELL: Because most of those scripts are being written by men. But a lot of young women who see your films seem invested in you in a way that they probably aren’t with a lot of other people.

STEWART: I think there are a few people like that. If I’m one of them, then it’s exciting, it’s weird, it’s cool. I hope to keep that one going.

MITCHELL: Is it weird to you?

STEWART: Well, obviously, that’s what we all kind of hope for. But I couldn’t imagine doing a project with the idea of how it’s going to affect people. It really has to affect you first, and if it does, then maybe it will affect other people… I think that people who don’t have that are clearly choosing things to become famous actresses. They’re clearly choosing things to make money. I mean, I love L.A.—I love living here. But I wish that we could make things without the need to hit a home run every single time. It’s a unique thing to Hollywood that if you don’t do that every time, then you’re considered a failure. But it’s like, “Well, are you making movies to be successful? Or are you making movies to learn something?” And it starts to influence people’s decisions. It makes sense because it’s hard to remain successful in Hollywood without figuring out what your path is and how people are going to perceive it. But I haven’t done that. I just got really lucky.

MITCHELL: That’s a part of success: figuring out what success means to you.

STEWART: I feel so extremely successful—and not just because I can greenlight a movie now. It’s because I’ve really only worked with people that I truly love, and I’ve only had bad experiences with one or two directors.

MITCHELL: What was bad about those experiences?

STEWART: I think it always boils down to people not being there for the right reasons, and not being there for the same reasons. It’s a miracle when things come together. But sometimes it just doesn’t happen—and when it doesn’t happen, you still have to finish the movie. [laughs]

MITCHELL: How do you get through when that happens?

STEWART: It just becomes more difficult, more thankless work. You find yourself occasionally having to lie… It sucks. I hate it.

MITCHELL: You mean lie to yourself about just getting through it?

STEWART: There are just certain moments that you thought were going to be a certain way, and because they’re changed, it’s not you and it’s not the character anymore—it’s nothing. You’re literally being an actor—you’re pretending—and that’s not what I like to do. When you look back at the film, those moments sometimes come through. But I think the way I approach things has something to do with growing up and seeing my parents go to work every day. You know, my mom is a script supervisor. It’s like the family business. It never had that feeling of entertainment. It was always more like, “Eh, it’s just a movie,” with that crew mentality, which is, “We’ve done it before and we can do it again.”

MITCHELL: So having watched your parents do what they do, what sparked in you the idea of, “I want to be a part of that, but not for the reasons that they’re doing it”?

STEWART: Well, my mom has now actually written and directed a movie, so her approach to it all changed very quickly. [laughs] But I was an extra a couple times, and I thought that was fun—it was something to do to get you out of school. And then when I first started auditioning, as I said, I didn’t get anything for a long time, so when I finally did get The Safety of Objects, it was like I discovered something. It was an experience where I felt something and tapped into something and got a part, so it was like, “Well, I guess that’s how you get a part.” I mean, it just sounds really obvious to every actor. Yeah, of course you have to really feel it. But it’s not so obvious to someone so young.

MITCHELL: It seems like every year you have these two wildly different pulls between the bigger movies that you do, like the Twilight films, and then the smaller ones that you’ve done. I remember a couple of years ago when you had both Welcome to the Rileys and The Runaways at Sundance.

STEWART: Yeah, I think it went Twilight, Welcome to the Rileys, New Moon, Runaways, then Eclipse, so it was like one of those movies between each Twilight movie.

MITCHELL: Was that just for you to remind yourself of why you wanted to do this?

STEWART: I just happened to have enough time to be able to take other parts between those first few Twilight films. But it wasn’t about proving to people that I had something else to give.

MITCHELL: With a film like Welcome to the Rileys, I wonder how you walk away from being that character. [In the film, Stewart plays Mallory, a teenage stripper who develops a friendship with a man, played by James Gandolfini, whose marriage is falling apart as he grieves over the death of his daughter.]

STEWART: Playing a character like Mallory is tough. Not to discredit anyone’s personal situation or actual life, but there are so many examples of girls like that, and a film can very easily become an almost clinical rundown of what leads someone to a certain position. It’s hard to play a part like that because you want everyone who has ever walked in those shoes to be like, “Yeah, I mean, that’s the way it goes…” Pity is a really odd thing with abused women. You don’t want anyone to think that you feel bad—even though you might. So it was just interesting to play that part and to work with James. I went down to New Orleans to do the film and lived by myself and trudged around the city. But walking away from that character… It probably still hasn’t gone away completely, but for the first little while afterwards, I was so sensitive and touchy in a way that my character would never be. I was so protective and defensive of young girls, and sex in general.

MITCHELL: Then seeing your performance in Runaways, where you play this girl who is trying to figure out what she wants to be while other people are trying to force her into becoming something else—it strikes me that they’re similar roles in the sense that both of these young girls are looking for a kind of family, but at the same time, both characters are incredibly mistrustful of most people. And in the case of The Runaways, you’re playing a character based on real person, too, in Joan Jett.

STEWART: And Joan is somebody who is so protective. I mean, Joan is covered in armor.

MITCHELL: She even wears her hair like a helmet. She’s somebody who knew that she was an artist, but at the same time, was being treated like a commodity.

STEWART: But I think it’s cool to come out of somewhere where you’re being pushed into this mold and then you figure out in that who you are. Maybe she wouldn’t have figured out exactly who she was if she wasn’t being forced into something else and fighting against it.

MITCHELL: It seems like Joan would be another hard habit to shake.

STEWART: She was. I went to do Eclipse right after, and I think the director of that movie might have said to another cast member that he had to beat the Joan Jett out of me. [Mitchell laughs.] For a while, I just walked kind of hunched over. Joan has great defensive tools, and I became a bit attached to them.

MITCHELL: Like which ones?

STEWART: Just the way she deals with people. I think we were promoting New Moon just as I was finishing The Runaways, and I remember going to Comic-Con with a Minor Threat T-shirt on. I was really happy and excited to be there, but I was so defensive and crazy. [Laughs.] It’s hard to deal with the press. There are always a lot of leading questions and opinions. Of course, our work is creative, and it’s subjective. But I was totally Joan Jett-ing out. We were doing interviews, and one wrong thing was said, and Joan has this crazy ability to just shut down and look at you like, “Well, I’m done now. Later.” It was so . . . I’m not like that, but . . . Yeah, I was then.

MITCHELL: The Runaways, though, must have come at an interesting time, because at that point people were just starting to have certain expectations of you. Do you feel like that gave you a perspective on it that you might not have had if you’d done the film before Twilight?

STEWART: Oh, yeah. The frenzy we were acting out in the movie was interesting because I had experienced it with the unique success of Twilight, where people would go absolutely bat-shit-nuts-flip-out-seizure-on-the-ground-crying in front of you. Then that thing of having people want to get in… Joan was so protective of me with the paparazzi. They were hounding our set like crazy. She was so concerned and emotional about it, and I was always like, “It’s fine. I’m fine.” But it bothered her a lot. We grew to know each other so well, so she knew that I wasn’t the type of person-even though a lot of people think of me like this—to not care. People think that I’m really untouchable, and that’s also translated into a lot of people thinking that I’m super-ungrateful.

MITCHELL: Where does that come from?

STEWART: I think people are used to seeing actors be wide open and desperately giving of themselves, and while I do that on a movie set as much as I can, it’s so unnatural for me to do it on television, in interviews, in anything like that. I also don’t find that my process as an actor is really anyone else’s business. A lot of actors have felt like that. I mean, there’s that awesome quote where Joanne Woodward said, “Acting is like sex: you should do it, not talk about it.”

MITCHELL: People talk about sex now all the time.

STEWART: Oh, I know. [laughs] But do they really talk about it personally?

MITCHELL: They sell it. I mean, there are people who have gotten to be famous by having sex tapes of themselves out there. You can’t be more forthright about that than, “Here I am having sex . . .”

STEWART: Yeah, but they’re lying while that video is being made. The act is in itself a lie. You’re faking something. The girl is lying there, she’s pretending that she doesn’t know the camera’s on, she’s getting banged, and “accidentally” it leaks out? Everyone leaks their own sex tapes! That’s a ploy to get famous—that’s not about the sex. It’s not like when Madonna did her Sex book, and it was an artistic endeavor where she acknowledged it and spoke about it and was so upfront about it. It’s different. It’s not upfront. It’s not honest. It’s a ploy to get famous.

MITCHELL: It makes you wonder what Joanne Woodward would do nowadays if she were just getting started.

STEWART: She’d probably be kind of like me. There are a lot of other actors, too, who do this because you have to.

MITCHELL: You have to?

STEWART: Yeah, you have to.

MITCHELL: Is there something that drives you to do it?

STEWART: Oh, definitely. I think there are a lot of actors who act because they have an impulse to do it and they can’t ignore it. But what I really mean is that they do the interview process because they have to. It’s a good bargain: If I can do this part then I’ll sell it. I just wish it wasn’t me who had to do it because it feels very unnatural.

MITCHELL: You don’t like talking about the process of making movies?

STEWART: No, I do—I love sitting down and having actual conversations. But I don’t do that sound-bite, be-candidly-funny thing. I’m so concerned with the right thing coming out . . . I know that people’s judgments are fast, and in a split second I will ruin it.

MITCHELL: Really? Having done this for as long as you have, you still feel like people have these sound-bite expectations of you, and that you either can’t do it or you don’t like to do it?

STEWART: I can’t do it. It’s not that I fight this urge to be easily consumable. It’s just that I put a lot of weight in what I do, and you and I can talk to each other in a certain way because that’s how people interact, but I don’t really know how to talk to the entire world. People cultivate these fully formed personalities. I’ve done interviews with actors who I’ve worked with who I really like, and I’m like, “Wow, look at you. You’re just going on… You don’t even know what you’re saying!” Then you watch the interview afterwards, and they didn’t really say much, but it’s interesting, funny, and engaging. Whereas I sit there and look a little bit too serious, and as soon as that happens then you’re uncomfortable and you don’t want to watch. It’s also weird talking about projects as an actor because you’re so in them. I would prefer to write a paper and deliver it to everyone via e-mail. [Both laugh] It’s too much to think about on Jay Leno.

MITCHELL: Well, in the context of something like The Tonight Show, people are expecting you to be that thing that you don’t want to be: a performer. But, at the same time, there is such a performance aspect to what you do. You see the irony in that, right?

STEWART: Yeah, but the performance aspect does go away on set for me. The reason I choose things is because I feel like this character kind of exists. So on set, it’s really more about, “Oh, man, I’ve got to do this justice.” It’s about not letting someone down.

MITCHELL: That’s a lot of pressure to put on yourself.

STEWART: Yeah, but I mean, it’s the only reason to do it.

MITCHELL: You like that pressure?

STEWART: Yeah. I don’t know why anyone does the job without that pressure.

MITCHELL: I know it’s an obvious thing to say, but you must get this all the time where people come up to you and say that you’re nothing like these parts you play.

STEWART: Yeah, I also get the opposite a lot, too.

MITCHELL: Do you?

STEWART: Yeah, a lot of times, I get, “Don’t you want to do something a little bit out of your comfort zone? You always play these really forward-thinking, strong, outspoken women.” But I’m like, “Are you kidding me?” If you look at the actual movies that I’ve done, the whole struggle is to get to that point, so it’s not something that you just have so easy…. But it’s okay. It doesn’t bother me. I’ve done okay so far.

MITCHELL: I think you’re doing okay. [laughs]

STEWART: Let’s just see if I can stay here and not get kicked out of the pool.

———

ELVIS MITCHELL: So the big question is: How are you, mom?

CHARLIZE THERON: My god, when was the last time I saw you?

MITCHELL: Oh, gosh. I don’t even remember.

THERON: I think it was at Jason Reitman’s reading at the LACMA [Los Angeles County Museum of Art] theater.

MITCHELL: Ah, yes.

THERON: That was hilarious. I was there for the reading that Jason held of The Breakfast Club [a staged reading of the 1985 film], and you were there.

MITCHELL: Did you have a good time?

THERON: Oh, I love that Jason does that stuff. It’s brilliant.

MITCHELL: When are you going to do one?

THERON: Never in a million years. I’ve even said to Jason, “I will jump off a building for you, but I will not do that.”

MITCHELL: But doing a reading is so much safer than jumping off a building.

THERON: No. I’m just not made for that kind of live audience where you don’t create a fourth wall. I take my hat off to those guys—I loved watching them. But performing like that . . . Frightening.

MITCHELL: What scares you about it?

THERON: It’s not disconnected enough for me, so it feels like a performance versus really creating a fourth wall and pretending like there is nothing. Some people are good at performing in front of people like that, but I’m uncomfortable at it. I think maybe that’s the difference between acting and being a performer. I don’t think I’m a natural performer.

MITCHELL: Well, that’s sort of shocking to hear—that there’s actually something that scares you. I think of you as being a kind of fearless person.

THERON: I am fearless when I think I’m alone. [laughs] As soon as there are 200 people in a theater watching me, I get really scared.

MITCHELL: Can you watch your movies with an audience?

THERON: Oh, yeah. I’m so not hung up on myself or weird about watching myself or having other people watch my work, because it’s not me. There’s a separation.

MITCHELL: I think that it’s interesting that you went from doing Young Adult with Jason to doing Snow White and the Huntsman, because you could almost say that your character in Young Adult was somebody who is living in a fairy tale of her own devising. It’s almost like you’ve done two fairy tales in a row, in a way.

THERON: Oh, yeah. And they’re both somewhat twisted. I mean, isn’t this all a metaphorical life? Some fairy tales are incredibly dark.

MITCHELL: Incredibly dark—and violent. I think of you as being somebody who expresses herself in physical movement, and there is a lot of movement in Snow White.

THERON: I move a lot in this film. It was important for me to get across this sense of urgency. I think it was also that I needed to find out why my character, Queen Ravenna, was going mad. At first, I didn’t really understand why she was evil or losing her mind, but once I understood that it wasn’t just the fact that her mortality relied upon finding Snow White, and that knowing that and not being able to do anything and being stuck in a castle . . . Well, I think that would be maddening for somebody like her. It reminded me a lot of Jack Nicholson’s character in The Shining—that idea that you’re stuck in this place and you can’t escape it, that cabin fever. All that stuff made me realize that Ravenna had to move. So a lot of that is in the movie. She has areas in the castle where she has more energy, like in this “fire” room where her mirror is, so she spends a lot of time there. And the moment that she does become still is really heartbreaking because it’s almost like watching an animal that should never be still, like a wild cat, become still. It just doesn’t feel right.

MITCHELL: There is an incredible look that Ravenna gives Snow White at one point during a scene where there is a wedding procession. As you’re walking up, you look at her basically as if you’re an animal and she’s your prey.

THERON: Well, Snow White is a real threat to Ravenna, and I think she truly realizes it then. Up until that point, she has always considered men the threat, and she’s kind of learned over the years how to deal with that. But women, for her, have never been an issue because they’re only good for one thing, and that is to maintain her strength. But she’s very intuitive, Ravenna, and I think she feels instantly that there’s something about this girl, Snow White, that’s different, and she doesn’t quite know what it’s for until the mirror tells her that Snow White will surpass her if she doesn’t deal with it-and then, of course, all hell breaks loose.

“You go through situations that don’t work out, and then all of a sudden you have this baby in your hands and you forget about all of that.” —Charlize Theron

MITCHELL: This idea of Ravenna being trapped in a cage is interesting, because I think that you’ve played a number of characters who are essentially, in some way or another, trapped—and very often isolated and lonely.

THERON: Well, I heard this amazing quote the other day. I don’t know who said it, but it really kind of hit me hard in the stomach: “The only difference between all of us is that some of us were loved and some of us weren’t.” And that’s really kind of just breaking it down to the most bare-bones idea. Our mechanics are engineered so that we can survive quite a lot, but I think our need to be loved is so great that it’s the thing that damages us the most. I think that’s something we can find in any person, though some people are more in tune with it or accepting of it or have moved past it and dealt with it or have a healthier thought process about it than others.

MITCHELL: It is kind of a through-line in your work, though—these characters who, in some way or another, crave a certain kind of contact.

THERON: I know that I’m very attracted to characters who don’t necessarily make it easy to be loved either. It’s not a judgment—I just don’t find that there’s a lot for me to explore with characters that are easy to get along with or who have these amazing attributes and are just easy to be around. I think I am definitely attracted to characters that make you work for it. They don’t just roll over. They’re tough, and you have to break through that exterior. I think that they’re the kinds of characters that society sees in broad strokes and kind of gives up on. They’re definitely harder to get through. But I’m fascinated by how you can find those broken bits inside of somebody like Ravenna or Mavis in Young Adult or Meredith Vickers in Prometheus. I think that I’ve definitely gone through periods of my life where I’ve really explored that . . . Maybe I’m done now, and I can at least move on. [laughs] But I’ve definitely explored that idea over the last few years in different ways.

MITCHELL: But Monster is the beginning of this period for you where you start playing these women who are willing to make this agreement with the world that they’re going to live their lives in a certain way, and people are going to have to come to them in some way or another.

THERON: I can’t speak for other actors or actresses, but god, I feel like we are all craving that kind of thing. I had to do a couple of these roundtables when Young Adult came out last year with a bunch of actresses whom I really admire, and I felt like this sub- ject came up quite a bit—this frustration of not having enough material out there that really challenges and explores and asks questions about who we really are as women. In cinema, I think we’ve been served a dish that has just been consistent with the very unconflicted madonna-whore complex of a female character—and it’s always shocking to people when a female character goes beyond that and an audience actually connects with it. But the audience is connecting to the character because it’s real. When Jason and I went to do Young Adult, we had no intention of creating a caricature. We wanted to go and make that movie because we believed that there was something about it that was really true, and that therefore if it’s true, then people will emotionally tap into that because we’re not fucking with them. But I hear actresses talking about this all the time—this idea that you sit in meetings and the studio says, “Well, you can’t do that because the audience won’t like that. They won’t root for you. It’s not sympathetic.” I think that we’ve been served this one dish for so long that we believe that it’s all that audiences want, but when we test them or throw something out there that has some truth to it, they seem to always respond.

MITCHELL: I just recently saw the director’s cut of That Thing You Do! [1996], in which you have a few scenes, and there’s a lot more to your character in that film than in the cut that was released. Have you seen the director’s cut?

THERON: Yeah . . . [laughs] I’m glad that you actually brought up that movie, because I got a call from Tom Hanks, who directed That Thing You Do!, when he was done cutting that film. I was like, “Oh, my god. Tom Hanks is calling me. This is amazing!” And then, of course, he was calling me to tell me that I was barely in the movie. But I’ll never forget it—and this is why he’s Tom Hanks, because he’s got such a way with words. He was like, “Charlize, I have some good news and I have some bad news. The bad news is that I have to cut some of your scenes. The good news is you are like Marilyn Monroe in All About Eve [1950].” [both laugh] I was like “What?” But that was my first real experience of understanding how narrative is sometimes more important than character, which I think is a good lesson to learn. Actors can be very precious about their work and their scenes, but I think good actors have a strong understanding of narrative and are very often not as precious about that stuff. They just can’t be because they understand what makes for a better film, and that it’s the job of the actor to work toward that, and then if you want you can go to acting class or workshops. But making movies is not workshops.

MITCHELL: I remember meeting you around the time of Monster. It seemed like you were a little anxious about the film because there was so much of you in it. It was a bet that you were making on yourself.

THERON: Well, look, it was also a little bit like drinking from the devil’s pond, because you know the risks that kind of come with it. I knew that the material was so tricky and that we were walking on such a tiny high-wire that that film was either going to be good or it was going to be really bad. There was no in-between. And then, of course, for it to work makes you realize, “Oh, I want that kind of challenge again. I want material that makes me feel that way again.” Young Adult is probably the closest that I’ve kind of come to that.

MITCHELL: With Young Adult in particular, it must have been incredibly hard to play Mavis in the way that you’re describing, where audiences can laugh her off and then also feel uncomfortable about it at the same time. What was that talk like with Jason where you discussed trying to find the humor in the story while still making audiences really work through it?

THERON: Well, that was just it—we had to make it be real. So we never thought about the jokes. We were very aware that there were a lot of things written in the script that were obviously jokes, but I think you kind of feel a movie out, too, as you’re going, and there were moments where certain jokes just felt like jokes and didn’t feel like they were really coming from the core of the character. And that’s when you really hope that your partner in crime realizes that and goes, “Well, that’s cheap. We’re trying to make a funny joke now just for the sake of making a funny joke and we don’t need to do that. That’s not what this movie is.” You can make a movie that’s more focused on the jokes, but Young Adult was not that kind of movie. I mean, I think there were moments on Snow White where I wished there was a little bit more of a sick humor toward Ravenna. But maybe the tone of the movie couldn’t really support that. So you always have to kind of figure out where you are and adapt to it.

MITCHELL: It’s funny that you say that because there’s a scene where Ravenna is spied on in the room by herself talking to the mirror. I thought that was really interesting because it invites the question: How much of this is only happening in her head?

THERON: That was the whole idea that we wanted. For me, that was the hardest part of the movie because it’s such an iconic thing: I mean, “Mirror, mirror, on the wall, who is the fairest of them all?” Everything else was so anchored in a kind of reality, and then this thing shows up, and it’s very hard to say these words nd have them have meaning. So we had to come up with a way to allow them to have meaning. I always felt like it was Ravenna’s subconscious talking to her, but that was also too obvious, so we had to find a nice medium where we were playing with the audience and saying, “Is she crazy? Is this only in her head? Or is this mirror actually more powerful?”

MITCHELL: So what was it like to make it feel like those words-“Mirror, mirror, on the wall”-are being said for the first time?

THERON: You can’t, and you almost have to give in to the fact that it’s never going to happen. Those words have been said a billion times. So I had to find a way to say them where I could feel like they were at least coming from a specific place. There are a few layers in there of madness and addiction and fear and sometimes even a kind of parental appeasing. The mirror is almost the only thing in Ravenna’s life that she has this somewhat pleasing relationship with, but it’s very abusive and it’s not a very healthy relationship.

MITCHELL: You think about how many scenes there are in movies where people play to mirrors. Was that in your head a little bit, too?

THERON: Yeah. The great thing was that Rupert came up with this incredible bronze mirror that’s not really a mirror, so it’s very hard to see your own reflection. I actually speak to a kind of mirror man. It’s like this bronze liquid statue that appears in front of me, and it’s more of a conversation with him. So that was helpful, too, because the mirror in the fairy tale is so specific to her use, and I didn’t want it to be about Ravenna looking in a mirror and her quest for beauty being the thing that drives her, because I don’t think it was ever really about beauty. I think it’s the idea that beauty could be power, and that with power comes immortality, and with power comes control, and all of these other things are blocking her heart.

MITCHELL: What you’re talking about brings to mind a question: What made you want to do Snow White and the Huntsman in the first place?

THERON: It was a combination of things. I saw a great challenge in taking something that was so iconic and turning it upside down and shaking it up a little bit, which I’d never done. And then I also saw a character that was such an emotional wreck and has never truly been explored in that way. I keep talking about Jack Nicholson in The Shining, but that movie came on television at a time when I think, in many ways, I was questioning whether I should do this film or not, and that was the thing that sealed the deal to me—that and one night at 2 a.m. I woke up and watched the end of Se7en [1995] and I was like, “Oh, my god. The queen is Kevin Spacey. She’s a tribal serial killer.” [both laugh] Believe it or not, I’d also never been in a movie of this size and scale and epic nature, and I just thought Rupert was such a visual guy with so much passion, so I was really interested to see what it was all about. I’m a huge Kristen Stewart fan, too. There’s not an ounce of her anatomy that knows how to half-ass anything. So everything just kind of aligned for me to where I felt like I would be an idiot not to do it.

MITCHELL: I think it was an interesting choice, too, because, for me, so many of the films that you’ve done have been about the relationship that women have with their own images.

THERON: A lot of the characters that I’ve played have also grown up questioning things because of how they were told to live or to survive. I mean, you can’t deny that those first couple years really instill in you some kind of an idea of how the world works. For Aileen Wournos in Monster, it was that you can’t trust anybody. “I’m homeless, no one will take care of me, everybody’s gonna fuck me over, everybody wants to have sex with me and use me”—that was the first 13 years of her life. Ravenna goes through a kind of parallel experience where by her mother she’s taught that if you are young and beautiful, then you will have power because people will want you. So when Snow White is revealed to be the fairest of them all, it really isn’t about beauty. And it also, in a sense, isn’t about earnestness or having a good heart. It really is about how we see ourselves as women and our place in the world. Men age like fine wine and women age like cut flowers—we wilt after a while. That’s just how the world works and that’s what we are led to believe.

MITCHELL: Ravenna is, in many ways, the ultimate example of how a woman’s perception of herself can lead to this horrible road being taken. Is there some conscious thing that draws you toward that subject? What kinds of questions about beauty does it raise for you?

THERON: I feel really fortunate that I kind of fall in between two worlds. I’m so grateful that I was raised by a mother who really instilled in me that my moral compass and achievements all had to come from a real place that had nothing to do with my beauty or how I looked. That was very big for her. I’m also now in my mid-thirties, so I look in the mirror and my face is changing, and I have a different relationship all of a sudden with myself. Your face changes, things change—that’s just kind of what happens. [laughs] It’s hard, though, in this industry, because I think so much importance is put on how you look, and I’m not brave enough to be like, “You know what? I’m just going to let it happen. Whatever. I’m so cool with every line on my face.” There are days when I definitely look in the mirror and go, “All right, I need to find a cream.” I can’t foresee myself ever going under the knife, but then again, I’m only in my mid-thirties. Maybe it’s different when you’re in your mid-sixties. I don’t know, so I don’t want to make statements about where I’m gonna be in 30 years. But as of right now, I definitely have a different relationship with the way I look. It’s not all-consuming. But I’m also human so I have days when I look in the mirror and go, “All right . . . Things are definitely changing.” I can see that.

MITCHELL: A lot of what you’re saying reminds me of the first time we spoke. You were with your mother, and you were talking about getting that kind of sup- port and also that kind of drive from having somebody around who has your back.

THERON: You know when girls say, “I’m a girl’s girl”? It has never felt right for me to say that because I don’t know if I’m a girl’s girl. I think I might be a full woman’s woman. I’ve been very lucky to work with some great women who know how to hit the ball back really hard. Even the younger girls, like Kristen Stewart, I never look at them that way. I love having women like that in my life. My whole company is run by women like that. And I think a lot of that comes from my relationship with my mother. I like women who have an opinion one way or the other or who have a great sense of humor and a great sense of adventure. I can be friends with women who are not like that, but I don’t have that hard emotional connection. I think we want to be around people that kind of push us and inspire us and maybe teach us.

MITCHELL: And listening to what you’re saying, it becomes a little clearer why this, for you, might have been a logical time to start a family.

THERON: You can’t really be too calculated about everything in life. I think I’ve gone through my life with the understanding that you’ve got to let go and you can’t think that you’re going to control your destiny. I think I made peace with that at a very young age because I went through an experience that taught me that as soon as you think that you know how your life is going to be, something in the universe will make you realize that you really are not that in control of it. So in terms of wanting to start a family, this was not how I ever foresaw it. But then again, I try not to be a prisoner to those kinds of thoughts or ideas of what I think my life should be or shouldn’t be. That’s why I’ve never had a five-year plan. I always knew that I wanted to have children. It wasn’t kind of something that I discovered later. I also never felt the biological clock ticking because I think I always knew that I wanted to adopt. It never meant that I didn’t want to have my own children—I always felt that if I were in the right circumstances then I would totally have my own children. My mother found a letter, though, that I wrote her when I was 8 years old. She just found it, like, two years ago, and it was a letter where I asked if she could take me to the orphanage because I would like to adopt a little baby. I think back then it was more like I wanted to adopt a baby to be my sibling, but even at that age, I had this awareness of adoption, so this wasn’t a last-minute thought. It was something that was always under my skin, that I knew would be a part of my life, and, to be honest with you, when I decided to start filing, it was very clear. It was like I knew that this was exactly what it needed to be. So then you go through the process, and it’s tough. It’s not the easiest process—and then again, I’ve never liked things too easy in life. But it emotionally knocks you out. It’s a really difficult thing to experience, but I never once faltered and thought that I didn’t want to go through with it. You kind of go through situations that don’t work out, and then all of a sudden you have this baby in your hands and you forget about all of that. You forget about the last three years of your life. You just realize that everything unfolded exactly the way it was supposed to unfold . . . Wow, I just went on forever there.

MITCHELL: [laughs] That’s the way this is supposed to work. How is he doing now? Are you sleeping much?

THERON: He’s great. I’ve been doing things myself in the sense that I haven’t had a night nurse or anything like that, so I’ve spent every night with him except for the nights that I’ve had to travel. I’ve had to make two trips to New York and one really quick trip to London and Paris, but other than that, I’ve been with him every single night of his life and done every feed. A girlfriend of mine was like, “Why are you doing this? Get somebody to help you!” But the truth is that I’ve realized how little sleep I actually need. There’s nothing about it that actually makes me want to moan. I actually love it, and when I’m not doing it, I really miss it. I was joking to my girl- friend. I said, “I want to do it because when he’s older, this is all I will have to hold over him!” I can’t do what my mother did, which is tell me every single day of my life about her labor and how long it was and how it was 36 hours of hell . . .

MITCHELL: So I see that you’ve found the secret of maternal guilt.

THERON: I mean, I need some kind of money in the bank here. I don’t know what I did in a past life to deserve this, but he’s such a good boy. And he has a grandmother who basically eats him up every second that she gets.