Raf Simons

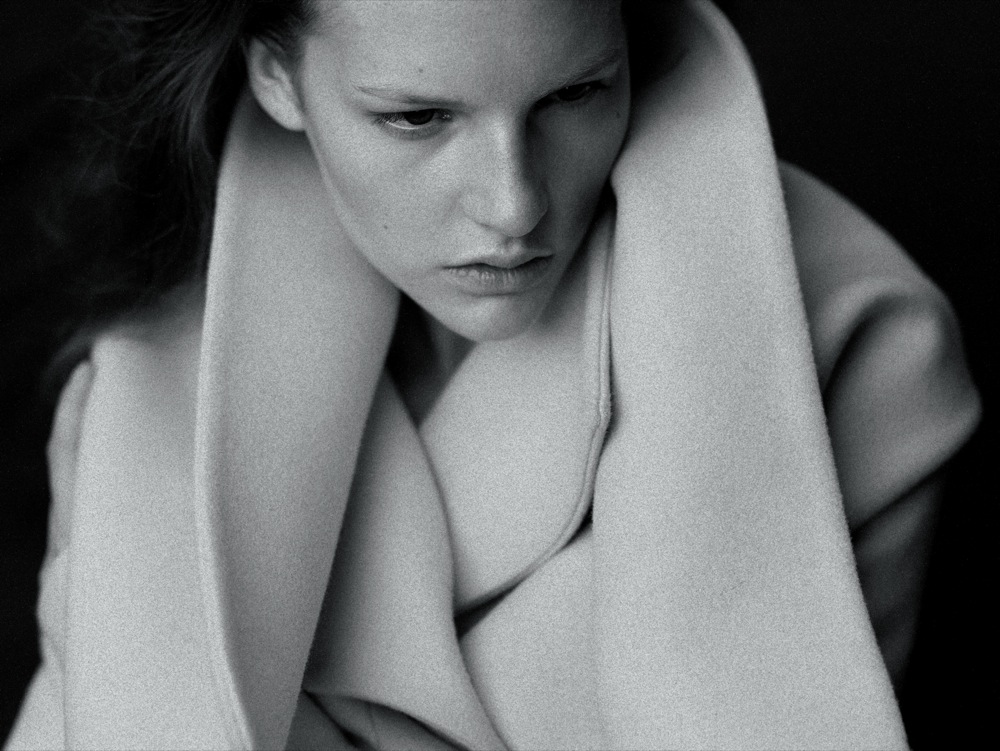

Raf Simons is the future. Still the future. The 40-year-old Belgian designer has long been the headlight for radical menswear. Throughout the ’90s and ’00s, his eponymous label showed how innovative design can embrace new technologies and fabrics and rethink traditional structures. In 2005, Simons turned from rogue independent to the man behind a megabrand, taking the reins of the men’s and women’s lines at Jil Sander. That label has always been known for its clean, utilitarian silhouettes, a precision that seems to particularly suit Simons, who, for the Fall 2008 womenswear collection, put the tailors on the dresses and the dressmakers on the tailoring. It was Simons way of again unsettling how we think of clothes.

Simons has many fans well beyond the closed doors of high fashion. Take Kanye West, the hip-hop superstar who has pretty much restyled the music world over the past few years. He’s never hidden his interest in fashion. When West went looking for inspiration in developing his upcoming sportswear line, Pastelle, he had the good sense to check out Simons. Their upbringings couldn’t have been more different, but Simons and West are both fearless individualists. Here they talk about style, music, and why it’s good to be the outsider on the playground. We started off asking them what they were like as children.

RAF SIMONS: I was born in this very small village in Belgium. It wasn’t really a creative environment. In school, creating was kept away from young people. The village was so small there was no outlet except for one little record store. I think that is where it started for me-just picking up records. I’m 40 years old, so it was LPs. The first LP I ever bought—you’re going to be shocked—was Bob Marley. Then I switched to Kraftwerk, Joy Division, and that kind of stuff. I was a bit dark at that time because I felt so isolated. But not only me, there were some other young people who felt that way. We loved to dress in black. I was growing up in the New Wave period, but that wasn’t allowed in school. I remember moments when they wouldn’t let four people dressed in black stand together on the playground. Then, before I graduated, I remember finding this book, and there was one page about industrial design. Basically, I ended up going to school for that. At that time there was a big boom going on with fashion in Belgium. The more I looked, the more I became interested. Before that I never even thought to become a fashion designer or anything like that. I started feeling that work when I was 19 years old, but I didn’t do my first collection until I was 27. I wanted to finish my education in industrial design first. My parents are very holy to me. They never said, “You should do this,” or “You should do that.” My dad had to go in the army when he was 16, and he stayed there. My mom was a cleaning lady her whole life. The only thing they said to me was: “Take it seriously. Do what you what you believe in, but take it seriously.” So the fourth year, I had to go for an internship. I went to Walter Van Beirendonck. I knocked on his door, and I was super scared-because I had nothing to do with fashion. But he was interested. He had absolutely zero interest in all of the fashion work I had faked to impress him. He just went straight to my industrial-design stuff. He said, “I really want you to come because, next to the fact that I am a fashion designer, I have this presentation in Paris and objects to make. I’m not a traditional designer.” I ended up doing that with him, and he took me to Paris, and I saw my first show, which was the third show for Martin Margiela. Nothing else in fashion has had such a big impact on me. It was a show where half the audience cried, including myself. I was just like, “What! This is fashion?” Only at that point did I understand what fashion could be or what it could mean to people. It was the “white” show, where all the models wore dresses in white and transparent plastic. Margiela had no money at the time, so the Maison ended up going to a black neighborhood in Paris and asking if they could use a children’s playground for the show. The parents said, “Yes, you can have the playground, but we want our children to be able to see it.” So little black children were standing with the audience in the front row. The children started to run over to the models, and they picked them up and held them around their necks.

KANYE WEST: For me, I realized the psychology behind having Jordans growing up—what it meant culturally, or what it meant to be a child just trying to fit in. When my parents divorced, my mother moved to Chicago, and my father stayed in Maryland. My mother lived in an all-black neighborhood. My father lived in an all-white neighborhood. When I got to Maryland, I had to adjust to a more affluent neighborhood than what I was used to in Chicago. Then when I went back to Chicago, I had to readjust to that. Then my mother and I moved to China for a year when I was in fifth grade. I had to adjust to a place where there was nobody my age, not to mention any black kids out there. Those were scary situations, but it made me able to open up my mind to other cultures and be accepting. And that is the greatest blessing, to have those experiences, because I can adapt to other cultures and still be who I am. So you see, with my style, there is a bit of Paris and a bit of Japan and a bit of the suburbs. A lot of people’s style looks very specific to one region.

WE LOVED TO DRESS IN BLACK. I WAS GROWING UP IN THE NEW WAVE PERIOD, BUT THAT WASN’T ALLOWED IN SCHOOL. I REMEMBER MOMENTS WHEN THEY WOULDN’T LET FOUR PEOPLE DRESSED IN BLACK STAND TOGETHER ON THE PLAYGROUND.Raf Simons

RS: That’s very good. Having your feet in the middle, you can see everything very differently. I think it’s beyond fantastic, actually. Dress codes and gestures and attitudes have always inspired me, as has youth culture in general, although now I question it more. If you analyze youth cultures over history, there has always been something strict about them-you have to be like this or like that. I’m actually surprised that in the 21st century, it can still be so present: They are still environments with walls around them.

KW: What I’ve noticed in the last few months, especially since my mom passed, is that everything is a cult. I don’t mean cult in a bad way, just that everything’s been cultivated for us. New ideas are the new roads, the dirt roads, that people have to pave. In order to go through the dirt roads, you have to get scratched with sticks, and you end up dirty if you have any new concepts. America is made not to have new concepts. It’s there to live alongside strip malls and be beaten by mundaneness. Even hip-hop is: “You can’t do this, you can’t say that. These are the rules of hip-hop.” One of my friends, Ludacris, wanted me to make a song called “Did It for Hip-Hop.” On the song I was gonna talk about how I didn’t do anything for hip-hop-I did it for myself. I did subscribe to the cult of hip-hop at one point, and I am very hip-hop because of it. But I have a lot of ideas that extend way further than the rules of hip-hop. In Japan you see guys that are dressed completely hip-hop, but they’re completely nice also. They’ll come up to you, looking like they’ll rob you and instead they bow. I find a lot of similarities between myself and the Japanese, because sometimes they look at something from the outside, and take the best of what they like about it, and then they’ll work extremely hard at pushing it to another level. They’ll take a piece of Americana, like jeans, buy all the jean mills, and then be the master at those jeans. From a music standpoint, I stayed in Chicago, where there’s no music industry, no outlets, nobody else that can make beats with me, not on the level of New York. Whereas in New York, everyone knew one another-you could be a small producer and sell a beat really quickly. So I would work on the beat so much that by the time I got to New York, the ones I was making were way better than anyone else’s. They were like, “Damn! Your beats sound like they’re completed songs!” ‘Cause people would just do beats that were a sample, like a really basic idea. Then they’d have a keyboard player come in, a person who’s a specialist at drums, and an engineer. And I’m doing all this in my room, right next to my mother, trying to beat five producers, taking the entire summer off, not getting a haircut, not getting any new shoes, ’cause I couldn’t afford them—and it’s like what Japanese people do: They see it and they end up doing it way better than the culture that made it. You once told me that if you didn’t do fashion, you would have done psychology.

RS: I like to find out things about people. I’m interested in them. But part of being a psychiatrist is also having to find out about people you don’t have an interest in.

KW: Right. That’s the problem. Whenever you take a job that you think you’re gonna love, there’s gonna be situations like that, where you also have to work with people who you’re not as interested in, until you get to the point where you’re at the very top of your game and you can just be like, “No, I don’t want to do this at all.” Until then, you haven’t reached your ultimate goal in life—a lot of people don’t realize that the ultimate goal in life is to not have to do anything you don’t want to do. Most people think the solution is to make a lot of money. The only problem is some people fall into the trap where money becomes the prison, and they end up having to do a bunch of things that they don’t want to do for money to get that couple weeks of vacation where they feel like they’re not doing anything they don’t want to do. So, for me, I try to design my life like it’s a big vacation every single day, every moment of my life. That’s the goal. Like, I wouldn’t rather be doing anything more right now than talking on the phone with Raf Simons, one of my idols and someone I’ve studied so much. I was in a Jil Sander store for an hour yesterday, looking at the collars and studying the way the marble print was put on the sweaters.

RS: That means a lot to me, and that’s also why I continue to do what I do. For me, I think that the 21st century almost doesn’t allow the beauty of something really small and out of the spotlight. I deal now with two labels, my own, which is a very small label, and Jil, which is a very big, corporate business label. I see the difference, and every day I work there I think, What is now best for me?—because I like both very much. My own mentality is to make it small, like my own environment. In that sense I relate to what you were saying because I enjoy just working with my people every day. But our society doesn’t allow that. Our society wants things to grow, and our society wants things to become bigger and bigger. Everything has to be put under the spotlight.

KW: Where I came from in Chicago, we didn’t have the term hip-hop. People didn’t even know how to state the way I dressed or acted and what my mannerisms were. It’s like how you said there were only a few people who dressed in black. I can’t even think of one person in my school who dressed like me. There are new boxes and barriers that I’m breaking down every day. Coming from the hip-hop community, one of the things that you’re never allowed to do is to speak about gay people unless you’re disrespecting them. You couldn’t be friends with gay people, you couldn’t be in the car with them, you had to look at them in a completely different way, like they weren’t even real people. I was working with my interior decorator, which was a big step for me because he was gay and I would have to ride in a car [with him] to go pick out fabrics and furniture. And I’d always think, What if a picture of me got shot and they put it on the Internet and they all said that’s my boyfriend? Then in hip-hop, they would be like, “Oh, Kanye’s gay, so we can’t listen to his raps because he broke a rule of hip-hop.”

RS: You break them, and you keep on breaking them, I would say.

KW: Yeah. Now that I’ve broken that, I feel much freer that I can be creative and not deal with stereotypes. America beats stereotypes into people. Recently there was this whole Bonnaroo situation. I didn’t realize that actual racism was still alive, because at a certain point, once you become famous, you’re no longer black or white, you’re just green-you’re just money. So when you walk in any store there’s a certain level of: “Oh, he’s not a black guy. He’s a famous guy now!” When I went to that Bonnaroo festival in Tennessee, they definitely reminded me that I was a black guy. On 12 port-a-potties they wrote in bold letters fuck kanye. They didn’t allow my crew to load on the stage; the promoter allowed Pearl Jam to do three encores. The sun was starting to come up, and the whole point of my show was that it was glow in the dark. They bled my cryo tanks so I wouldn’t have smoke. I felt so naïve, ’cause it clicked in my head: Oh, wow, this is really done on purpose.

RS: Being popular, is it something you want?

KW: I wrestle with it every day, because you still have to figure out how to use it in a good way. It’s like a girl being beautiful. It can be a gift or a curse. It’s like you could be one step away from being Kurt Cobain. Or you could be like Ralph Lauren, where you take your influence and help paint the world. Basically, I work constantly on coming up with ideas to paint the world.

RS: I wonder if you still find it necessary to dress a certain way when you perform. I’m just thinking back in time, when there were performers that constantly created revolutions. That’s how it started for me, you know? The musicians I was interested in I liked even more because they were such amazing chameleons. You have people such as David Bowie. In a way, I could compare him to you. You are a 21st-century boy, you know? I mean, Bowie goes to Berlin, and 9,000 people go to his concert expecting him to look like Ziggy Stardust, and he looked like the Thin White Duke. If you’re interested in popularity, it’s also very clear in today’s society, that that is the way to make yourself popular, because changing is ultimate freedom.

THE WAY THAT I DESIGN NOW, IT’S COMING OUT OF ME, BUT IT DOESN’T LOOK LIKE ME AT ALL. I SEE IT AS MY RESPONSIBILITY TO TAKE IT VERY FAR AWAY FROM ME. I THINK THAT’S THE ONLY WAY TO REFRESH IT AND KEEP IT INTERESTING FOR A BIG AUDIENCE.Raf Simons

KW: Well, that’s who I am now. When I delivered the “Flashing Lights” video-where the girl was very, very voluptuous, as opposed to what was always on TV, and a very instantly-would-get-somebody’s-dick-hard type girl-I’m like, “This is what I grew up on, and these are the type of girls that I like.” And then I mixed it. I juxtaposed super-huge titties with Margiela shoulder pads, which had never been done, with a Ford Mustang in the middle of the desert. Then I juxtaposed voice-over rapping, where I’m not in the video at all, and then I get killed at the end-it’s like, I don’t give a fuck what people want from this record, this is the idea that I want to show. And then after that I went onstage and designed a stage show where I was the only person. I don’t think I could have been in the place to really say, “Fuck what the ideas were before, what people expect of me,” if I didn’t have that situation with my mother, that great loss. Because when you suffer a big loss like I did, it’s like, What else can you lose? The reason why people are always scared is they’re afraid of losing whatever it is they have. And I think, in life, people want happiness, and they want a bit of their self-esteem back. People are so scared to lose their worldly possessions. So as an entertainer, am I gonna say something where I get so much backlash that I lose everything, that I lose the ability to sell records, that I lose the ability to keep a lifestyle? For me, I wouldn’t care if I died broke. I wouldn’t. I’d rather give my kids the same ability that I had, to hustle and to create their own way, than to leave them money.

RS: So how are you going to solve that? [laughs]

KW: I just do exactly what I want to do, just like you do. Jil Sander-okay, I’ll just give away one of my main ideas for my clothes. One of the bases for the finishes for my label is the lack of finishing. It should be theatrical. The fabrics should be great. But no gold zippers. I say “Jil Sander,” like, about 25 times a day when I’m talking to my design team-

RS: I’m scared now, Kanye. [laughs] But I often have a worry in fashion that you can do it a different way only until a certain point, and then you’ll just be kicked out. In fashion you try to change something, try to make people also think about what it is, and not just try to produce and produce and produce for business. Fashion as a creative art is always seen as something that is ahead, but only because it’s so sped up. I think it will become only more and more complicated, along with all other creative outlets-

KW: I have this conversation all the time about the arts, how they are commercialized—especially rap music, at a certain point, when it got so big and there were, like, super-megastars who couldn’t rap at all, and they were making so much money. At that point, that’s when hip-hop started to die. That took it down a level. Like in Middle America, you’re not allowed to have any art in your clothing. You can’t be expressive, or people will start talking about you.

RS: Do you define yourself as a rapper?

KW: Yeah. As a joke, whenever I go through customs and have to fill out what my occupation is, I put rapper, because it’s almost looked down upon. I used to put rapper on my applications to get a job; the manager would pull me to the side and say, “Man, I’m gonna just tell you—for real, you shouldn’t put rapper on your application.” So now, because of that, I always put rapper.

RS: I never feel I am a fashion designer. I have even found it problematic that the world defines me as a fashion designer. To me it’s more like, Yes, it is what I do now, but it’s far from my only interest, and I could see myself doing so many other things than fashion. It gives me a certain kind of fear for the future. If I have the interest to change to a very different field, I’m scared people couldn’t see me like that anymore because they define me as a fashion designer. I find it very intense, fashion. At one time I was doing only menswear. I was also creating art and teaching at university-that was all combinable. But, you know, once you have a label where you deal with men’s and women’s and you do six runway shows a year-accessories, campaigns, et cetera-there’s a lot less space. I think it’s different when musicians enter fashion. A lot of those collections are done by teams. Maybe a music performer is over-viewing, or the music performer is the name-carrier of the brand. It seems to me like it’s a side career. There are rappers who start a brand, and then it looks “rap.” The way that I design now, it’s coming out of me, so there’s a lot from me, but it doesn’t look like me at all. I see it as my responsibility to take it very far away from me. Even my own brand became an abstraction. I think that’s the only way to refresh it and keep it interesting for a big audience, because what you yourself are representing, it’s only for a very small group of people. The bigger the brand, the bigger the responsibility, because you have to think of all these kinds of different cultures, different environments, different people, different psychologies . . .

KW: The psychology is really important. When I bring up my own clothing line now, it has to be a practical joke, because I haven’t brought it out yet. But the thing is, as I’m working on it, I’ve learned a lot of the different things that you’re saying about a line being too connected and saying: “Okay, this is a line, and it has to have it’s own voice. It has to represent something that’s not out there.” And as I speak on it right now, my words have no weight. People read this in Interview magazine, your words will be in people’s minds in bold, and my words, when I bring up clothing or designing, will be in light gray and “Get the fuck out of here, you rapper,” until I do something that is basically the opposite of everything that you just said.

RS: Maybe we should start something together. Maybe you should buy my brand, and together we’ll go do something completely different. Maybe that’s what should change. Because that’s also what the future is going to be about, it’s going to be all crossovers, everywhere, finally. I was criticized in the past, believe me. I was criticized because I touched all the fields and had an interest in all of them. But I think that now is going to be the time of crossovers, especially in fashion-more than in other fields. A general thing that I feel so strongly is that the fashion audience is bored so quickly. They are bored sometimes even before they see a show. It is not something I blame the audience for—I try to find solutions. I try to keep their attention, because I want their attention. Don’t ask me why, but I want it. I don’t want the attention on me as a person. I could never do what you do; I am not a performer. It makes me nervous and scared. But I really need that attention-because I’m proud, because I believe I have something to say. And the problem is we’re going to have so many crossovers that people are going to be bored with those crossovers in one day. That’s something that I’m really questioning. Is the motivation business? Is the motivation to keep the audience interested? Are we going to come to a point where the new is not going to be able to be new anymore? Because it’s such an important word in fashion, the word new. And it makes me think a lot, because I deal with one brand that has always tried to be about the new and that has always been dealing with coherence. Jil Sander has always been a very coherent brand. Jil as a person had no desire to be in the middle point of the fashion arena to catch attention. But I see, also, that the audience is in this moment looking for that. It is something you have to deal with if you are responsible for a business, and you will be criticized and adored. You cannot have adoration without -being criticized.

KW: Yeah. Well, right now it’s just criticism. [laughs] No, it’s not criticism, it’s pessimism. I’m not anywhere near as well-off as people would think for how big my name is, because I put everything back into the album, into recording. I put everything into investing and doing an independent clothing line because I refuse to do a licensing deal where people are like, “Put your name on the front of this shirt, and this is what you do . . . ”

RS: I know what it is to go somewhere where you haven’t been, and a whole arena is sitting there with lions waiting for the meat to come in. I know exactly the feeling I had when I had to go to Jil Sander and I had never done womenswear. It’s a challenge. But it’s fantastic. I like the idea of constantly changing, like a chameleon. But it’s complicated. Fashion, just like music, deals so intensely with new generations of people who come in and really appreciate change. But in music, even if you’ve been in the business for 50 years, you stand on the stage, and you do that song from 50 years ago, and the audience will love that same song-they will respect it and respect you for it. In fashion, it’s not like that. I cannot go onstage and bring out the same collection from 10 years ago. That wouldn’t work. I would be dead.