New Again

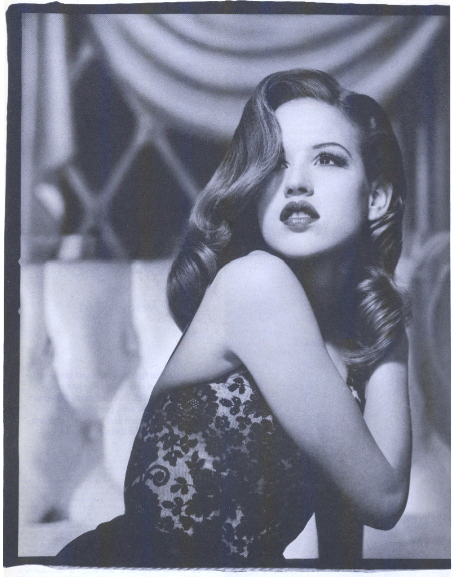

New Again: Molly Ringwald

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

Molly Ringwald gave a voice to every awkward teenage girl from 1984 to… forever. From Sixteen Candles to The Breakfast Club to Pretty in Pink, Molly mapped out all the ups and down of teen life, and she did it with sincerity. When we met Ringwald back in 1985, she was 17 years old and working on Pretty in Pink, directed by her mentor John Hughes. She never, as child stars are wont to, came off as spoiled or robotic, but laughed, gushed about boys, and told us fanciful stories about strange summer camps in France and living in New York.

Now, Ringwald is 44 years old, married with three kids, a published novelist, and set to develop a new show for Lifetime. The girl is on a roll. In her series, Ringwald will play a mom of two returning to her hometown and facing her not-so-perfect past. We don’t know how the show will turn out, but here’s to hoping Ringwald will once again embody the type of real women we don’t often see. —Melissa Belk

Molly Ringwald

By Margy Rochlin

A publicist who worked on Paul Mazursky’s Tempest once said that after she saw the film she had remarked to a co-worker that they were about to embark on the ruination of yet another youngster’s life. In other words, 13-year-old Molly Ringwald’s screen debut was so precociously good that the fame and attention this publicist would help generate would lend considerably to Ringwald’s chances if becoming one of those movie brats—freakishly affected, perpetually on stage, hopelessly unable to lead a normal life.

Tempest won her a Golden Globe nomination for Best New Actress of 1982. She did a few television movies, Packin’ It In, and P.K. and the Kid, and a feature that was an unqualified flop, Spacehunter: Adventures in the Forbidden Zone. But in screenwriter John Hughes’ directorial first, Sixteen Candles, something clicked. The moderately successful teen-oriented film was criticized for its blatant racist/sexist humor, but Molly Ringwald, as the touchingly self-conscious Samantha, performed as if she were in another film entirely.

Still, despite the Tempest publicist’s predictions, no baby monster emerged. Ultimately, the most noticeable un-teenagelike trait was Molly’s display of that singular quality held by adolescents who must tread that middle ground between the adult world and that of their peers—something like a wily sophistication combined with bedrock youthfulness and naiveté. By the time Ringwald completed Hughes’ second film, The Breakfast Club,” and Surviving, a television movie about teenage suicide, if she had established anything it was the fact that she stood above the neo-Rat Pack of young, talented actors currently dominating the screen.

Born in Sacramento, California, in 1968, she began her career at the age of three, singing songs with the Great Pacific Jazz Band, led by her father, who is blind jazz pianist/banjo player Bob Ringwald. Two years later, she cut an LP, Molly Sings, which included tunes like “I Wanna Be Loved By You” and “Oh Daddy.” She became involved in acting when her older brother Kelly and sister Beth participated in community theater. Her interest finally won her a role as the Dormouse in Alice Through the Looking Glass. In 1973, she was included in Truman Capote’s The Grass Harp. By 1977, she had landed a role as one of the orphans in the San Francisco-Los Angeles company’s production of Annie, and her family moved south. Two years later she was cast in the television sit-com Facts of Life. She was cut after one season, which reportedly left her “devastated.” Her parents told her she would overcome the loss. Her parents, as parents often are, were right.

Currently a junior at the upscale West Los Angeles high school, Lycée Français, Molly is in the midst of filming her third John Hughes film, Pretty in Pink. The story, she says, is about a poor girl going out with a rich boy. “Basically,” says Molly, “It’s about pride and honor and respecting who you are.”

Molly Ringwald and I met early one morning at a San Fernando Valley coffee shop near her home. Like most junk-food-obsessed teens she ordered hash browns, a Danish, coffee, strawberries, and a sausage patty. (“Ugh,” she said later when the latter arrived, “This looks like dog food.”)

We opened by discussing something that is certainly one of her areas of expertise—filmic adolescence.

MARGY ROCHLIN: How many more years do you think you will spend playing screen teenagers?

MOLLY RINGWALD: I suspect this is my last. By the time Pretty in Pink comes out I’ll be 18. I’m going to grow up and I don’t see any point in playing someone 17 years old when I’m 25. Pretty in Pink ends at the senior prom. I figure this is the perfect way to end the trilogy.

ROCHLIN: You must read a lot of scripts. What dumb clichés would typify one for a bad teenage-oriented film?

RINGWALD: Usually the kids are portrayed as very one-dimensional. Like these mindless animals that just have three things on their minds: getting laid, getting drunk, and driving real fast over Mulholland Drive. Oh, and hating their parents. I can’t stand films that make the kids out to be heroes and the parents to be imbeciles. I mean, a lot of people said The Breakfast Club was anti-parental. But it wasn’t that way at all. It wasn’t saying that parents are bad, it was saying that these kids had those feelings about them. I mean, maybe Alison (Ally Sheedy)’s parents weren’t that bad—but she felt they were. Oh, also the drug aspect. Not all kids like them.

ROCHLIN: But in The Breakfast Club the five disparate characters remained isolated from one another until they all smoked a joint. Then they shared their troubles.

RINGWALD: That’s the thing. A lot of people don’t realize that not everybody gets high. John Bender (Judd Nelson) didn’t, for one. It was his pot, but he didn’t do it—which says a lot about why he does have the pot and why he doesn’t smoke it. He has it because it makes him feel above other people. He likes to get other people high and then watch them act like assholes. Alison didn’t get high either. She was terrified of it.

ROCHLIN: What do you think you will be allowed to do once you’re in a post teenage film?

RINGWALD: Live away from home? [laughs] No, actually, I don’t mind playing a young person, just someone not in high school.

ROCHLIN: When do you plan to get your own place?

RINGWALD: If I tell, will you print it?

ROCHLIN: Yes.

[Molly looks at her publicist, Susan Geller. “Should I?” she asks. “Will you be going out with him by August?” says Geller. “My instincts tell me that I will,” says Molly, digging through her purse for her wallet.]

RINGWALD: Here’s a picture of him. He’s Dweezil Zappa. [Frank Zappa’s eldest son.]

ROCHLIN: How did you meet him?

RINGWALD: See, I’m friends with Moon [Zappa, daughter of Frank Zappa] when I first met him I was going out with Michael [Hall, of Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club]. When I met Dweezil he was 14 and I thought he was really cute. Anyway, I’m really intimidated by beautiful people. Beautiful guys, especially. Like, not intimated, but I sort of think the worst. Anyway, he would never really talk to me and if I were in the room he would leave. The first time I came over I never even saw him until I was just leaving. Moon came running down the stairs and said, “I want you to meet my brother. Dweezil is painfully shy.” Anyway, I was hanging out a lot last summer with Moon and Dweezil and their cousin Keemo. I never really thought anything about it. And just recently Dweezil was going up for a part in Pretty in Pink and he called me up and we started talking and started doing stuff again. And I thought to myself, “I really like this person an awful lot.” Then it just happened. Now we’re going out.

ROCHLIN: Is Dweezil the same guy that you said was “15, but really mature,” but would not name in another interview?

RINGWALD: [laughs] No. That was somebody else. But, that guy was 15 and not so very mature. Age means nothing to me. I swear to God, I thought I was only going to out with older guys my whole life. Then all of a sudden there was this major turnabout that started with Michael. But I haven’t really gone out with that many guys to really say anything about it.

ROCHLIN: In California you must be 16 before you can get a license. Does that mean you always have to drive when you and Dweezil go out?

RINGWALD: It’s funny. You know, most kids can’t wait to drive as soon as they turn 16. But Dweezil doesn’t even care. You know, Frank doesn’t drive and Moon only just got her license and she’s 17. Dweezil had no intention of getting his license. I told him, “This is ridiculous. I don’t want to drive every place.” So the other day I got home from work and I really wanted to go see him, but I was so tired. I told him, “God, I wish you could drive.” And he said, “Well, you know I’ll be driving very soon as per your request.” [laughs]

ROCHLIN: Do you have a certain type that you’re attracted to?

RINGWALD: Not like a blueprint or anything. I like guys who are sensitive. I think that it is real important for someone to be really honest and open emotionally. I’m really an emotional person. If I’m that way and the guy isn’t that way I just really feel like a jerk. I also like guys that really intelligent—like Dweezil is. Also talented. And not egotistical.

ROCHLIN: What is the difference between mature and grown-up?

RINGWALD: I think you can be mature without being grown-up. You can also be grown-up without being mentally mature. One of them is forced, while the other one is your choice.

ROCHLIN: You’ve said when you were 14 you went through a brief rebellious period.

RINGWALD: It wasn’t very rebellious. I didn’t do it with drugs or alcohol as much as with my physical appearance. I rebelled with my hair. I started dying it every different color. Black. Dark, dark brown. Kind of blonde—I’ve never gone full-on platinum blonde, which I’ve always kind of wanted to do. Dirty blonde streaks. Red and blonde at the same time—which was an accident. Pink. [laughs] When I first met John Hughes I had used this hair coloring stuff, which turned my hair green. Greenish-brownish hair with a blonde streak in the front—really hideous. John thought it was pretty funny.

ROCHLIN: What spurred the mini-rebellion?

RINGWALD: I think you get to this certain stage where you just want to break away from your family and have your own identity and then you come back. Fortunately, it was a very short-lived rebellion. I think it probably hurt my mom more then it did my dad. It was all pretty visual and my dad’s blind—I don’t think it affected him that much.

ROCHLIN: In preparation for your role in Tempest, you and your family moved to New York City.

RINGWALD: Paul Mazursky really wanted me to get the feeling of New York, so he stuck me right in the heart of the Greenwich Village, on Carmine and Bleeker, right above a street fair. It was bizarre after California. Like, people urinating in the hallways. The place we stayed in was so strange. The guy had left everything in its place. It was so funny—wine glasses, books, records, everything totally left out. It was like moving into this apartment that was totally lived in—except for this one wicker basket that was all tied up with strings.

ROCHLIN: What was in the wicker basket?

RINGWALD: Well, my brother and I got so curious that one day when my mom was out we untied it. We opened it expecting to find jewelry or something. It was all this S&M stuff—leather and books and stuff. We’d never seen anything like it before and we just looked at it then we tied it back up and left it alone. I finally had to move the wicker basket out of the room because it really grossed me out.

ROCHLIN: Sounds very trashy.

RINGWALD: I expect the dirtiest book I ever read was like Jacqueline Susann—pretty tame. Oh, actually, I read a dirty book while I was in France at this summer camp.

ROCHLIN: At summer camp?

RINGWALD: Yes, after The Breakfast Club, I wanted to get away, just relax. I decided to go to Europe with my friend, Monique, who is bilingual. She had told me all about the camp—that it was by the beach, that it was fun. I pictured a beautiful beach with flowers everywhere and people in long, white gowns drinking wine for breakfast. Anyway, we got there and walk up this rock hill with no flowers, no daffodils, no anything. I was already thinking, “I don’t know about this…” Then we got to the mess hall and they split people into groups. Then they started chanting. And I said, “Monique, what are they doing?” And she said, “They’re praying.” And I said, “Yes, Monique, but why are they praying?” And she said, “They pray before and after meals?” It turned out to be an Orthodox Jewish camp. I mean, like, I’m Christian, and I don’t speak Hebrew. I felt very alone, very American, and very stupid. Anyway, while I was at this camp I had nothing to read. Monique brought this book with some corny title like, There Should Have Been Castles…. Or something like that. It was a really thick book and all smut. I was so ashamed of myself because I was so engrossed in this book; I couldn’t put it down. But there was nothing else to do.

ROCHLIN: Given the fact that you were clearly out of your element, how did you handle the situation?

RINGWALD: I ended up running away after I couldn’t get a hold of my parents. The funny thing was that when they sent the police out after me the only picture Monique had was of my friend Matt and me sitting on Santa Claus’ lap. [laughs] Anyway, I came back before they caught me. I had left my clothes there and everything. I just needed to get away. I felt like Woody Allen in Annie Hall when they catch him playing bumper cars in the parking lot and he tears up his license—I really have a problem with authority. I mean, they’d wake you up at six o’clock in the morning with Hebrew songs over the loudspeaker. Another funny thing was that I was sent the Surviving script while I was at this camp. I flipped when I read it. I said I have to get a hold of my parents, of my agent. And they said, “No,” because it was the Sabbath. When I finally got through to my parents I was sobbing. I had to fly home by myself. The whole thing was an incredible experience that really made me grow up a lot. When I got back, talk about appreciating your parents…

ROCHLIN: Warren Beatty owns the rights to the Edie Sedgwick story, it has been said that you will play the role of Edie, but that you aren’t old enough to play the part yet. Is the project just sitting around waiting for you to hit the right age?

RINGWALD: Well, I don’t know if it is exactly for me. I mean, Warren Beatty bought it around the time I said that I liked it. But I don’t want to be so arrogant as to say, “Yes, he bought it for me,” because I don’t know if that is really the case. I’d like to do it. I’d like to work with him. I’d be really happy if I could do it because it’s my dream project, but I don’t really want to say I’m going to do something and then be humiliated if it doesn’t turn out.

ROCHLIN: What draws you so strongly to Edie Sedgwick’s character?

RINGWALD: Well, basically it isn’t her. She is like a focal point of an era that interests me so much—that whole underground scene. It’s so different then anything I grew up around. Like another world. One thing that does attract me to her is that although I’m different than her we’re also alike in some ways. Like, style. I’m really attracted to her style. And wanting to try and do everything. I’m like that too. Also, I look a little bit like her, I think.

ROCHLIN: Have you seen Ciao! Manhattan?

RINGWALD: Yes. It was depressing. I felt like I was going through it with her and it made me physically sick. I was with my friend who gets grossed out by the sight of needles and stuff and we both waked out of there just like this. [grimaces and clutches her stomach]

ROCHLIN: The parallel has been drawn that Edie Sedgwick was very much taken advantage of and manipulated in the same way young actors are used then discarded.

RINGWALD: People say to me, “Aren’t you worried about people taking advantage of you?” I feel that I can’t be taken advantage of unless I let them. Edie wasn’t really in the position of stopping people from doing that to her. She allowed people to take care of her, then she would break away, go out on her own, be crazy, then come back and let people take care of her again. I’m not that way.

ROCHLIN: Is it correct that your mother is concerned about the Edie project because it will require nude scenes?

RINGWALD: She doesn’t not want me to do Edie, she wants me to do anything I feel is good. I think she’s concerned about it; she’s a mom, you know. She doesn’t want me to take my clothes off. I don’t want to take my clothes off either, but if I felt it was essential to the script, then I would. It has to be handled very tastefully, though. Like, I thought Splash was handled very tastefully.

ROCHLIN: You plan to attend college after you graduate from high school. Is that inspired by the Brooke Shields/Jennifer Beals/Jodie Foster decision?

RINGWALD: Well, no. My parents always raised us with the idea of having college in mind. You sort of need a college education. It’s part of life. It’s something that you do—like going to your prom. [laughs] I’m not going to go right after high school. I think I need that time when I’m not going to school or working.

ROCHLIN: What was the last book you read?

RINGWALD: I read The Crucible for school. And I’m reading The World According to Garp, which I already read, but I’m reading for school now. I have the best English teacher—he’s so hip. Like, we have these book lists and when we were doing contemporary playwrights he included Torch Song Trilogy. He goes, “I know your parents are going to kill me, but it’s a good piece of work….” The last book I read on my own was Bright Lights, Big City. It reminded me a lot of Catcher in the Rye, because it was so specific and you really felt like you went through it with him. Catcher in the Rye is one of my favorite books. I read it with my dad and everything.

ROCHLIN: You told me earlier that you enjoy writing. Do you mind the solitude it demands?

RINGWALD: Primarily, I don’t like being alone. I haven’t been alone since I got a boyfriend. What I do like about being alone is being able to do whatever you want and it’s for yourself. I’ve been keeping a journal for the last three or four years. I write in composition books, so I have this huge stack of them. It’s so neat—I can go to the stack and go back through them and put in pictures and flowers and everything. Nobody else reads them and I’m burning them before I die.

ROCHLIN: Would you like to write film scripts?

RINGWALD: Eventually, yeah. I’ve learned a lot from John Hughes. He has one of these great, uncensored minds. Meaning he doesn’t edit things in his head. He edits things when they get down on paper; ideas just run rampant in his mind. A lot of people are afraid to think things. They have to be told what to think and feel and he is just really free about things like that. He has a great imagination and I think that’s what makes him a great writer. He is a great observer too.

ROCHLIN: You displayed a beautiful singing voice in Tempest. Do you intend to eventually establish a singing career for yourself?

RINGWALD: I don’t know. I sing at this place called Stevie G’s and another place called the Money Tree. I may do an album one day. You know, it really grosses me out when actresses go on the Carson show and they can’t even sing. The only difference is that I can sing, but not everybody knows that. Automatically everybody thinks of me as an actress who is trying to sing. And if I weren’t me I’d probably think the same thing.

ROCHLIN: Has music always been an influential part of your life?

RINGWALD: When I was in second grade we had an assignment to pick a famous American. All the girls were picking nurses like Clara Barton and Florence Nightingale. The guys were picking George Washington and Abe Lincoln. And I picked Bessie Smith. At the time my mom had given me this perm, that was almost like an afro—more like Ronald MacDonald, really hideous —and I had this old dress that was real big on me, and I did this whole thing on Bessie Smith. See, I never really had that big of a distinction between black and white people, because my parents always gave me black baby dolls and stuff like that. Anyway, so I always thought that when I grew up I’d be black, sing jazz in a nightclub and it’d be great.

ROCHLIN: The reality must have been a tremendous letdown to you.

RINGWALD: I know, it’s like jazz doesn’t even exist anymore.

THIS INTERVIEW INTIALLY APPEARED IN THE AUGUST 1985 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again, click here.