‘Truth Eats Lies’: Marlon James Creates a New Realm of Fantasy Fiction

On the first page of Marlon James’s phantasmagorical epic adventure novel, Black Leopard, Red Wolf, the narrator declares, “Truth eats lies just as the crocodile eats the moon, and yet my witness is the same today as it will be tomorrow.” That short passage packs together all of the potent power of the 48-year-old Jamaican author, all of his brash assurance and gorgeous mythical imagery. Perhaps no other contemporary fiction writer takes such risks and uses such provocative, sensual descriptions as James (who masterfully mixes in smells and sounds as well as sights to build a world). He’s most known for his third novel, the 2015 Man Booker Prize–winning A Brief History of Seven Killings, which brought him back to the violent streets of Kingston, Jamaica, at the tail end of the 20th century. (James moved to the United States in 2007 to pursue his master’s in creative writing—as well as, among other reasons, to escape the rampant homophobia of the island country.) It takes artistic guts to switch from hyperrealist social fiction to a fantasy trilogy that blends African myths and history along with a hallucinatory cast of characters that includes witches, giants, shape-shifting animals, and a gauntlet of monsters, tribes, and necromancers. In this first part of “The Dark Star Trilogy,” an irritable mercenary named Tracker (known for his strong nose) is hired to locate a missing boy, which kicks off a surreal and often brutal quest across the African continent. To preempt any critic who presumes that the author is merely bandwagoning onto the success of recent popular fantasy fiction such as Black Panther and Game of Thrones, James has been dreaming up this fantastic universe for years — with plenty of the hard academic research required to preserve the folklore and symbolism of sub-Saharan Africa. It is, at all times, running on his wicked prose and sterling imagination.

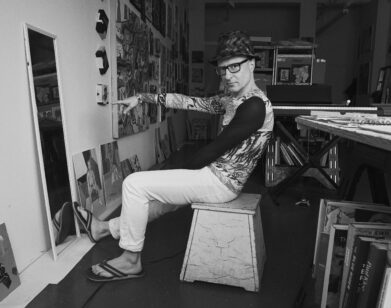

James splits his time between Minneapolis, where he teaches fiction at Macalester College, and Williamsburg, Brooklyn. A few days into the new year, he spoke to the writer Louise Erdrich about the makings of a myth, the music of street noise, and a lifelong love of cooking.

———

LOUISE ERDRICH: To start, your book is so intensely rich and vivid. There’s a child made of smoke, a leopard who switches species, a giraffe boy, a moon witch, a talking buffalo, a vampire lightning bird — I love the vampire lightning bird. There’s Tracker, whose eye was gouged out and replaced by an eye borrowed from a wolf. Reading this book, you can smell the history of a room, of different places, of a piece of cloth. And I’m describing just a tiny corner of this world you’ve built.

MARLON JAMES: A lot of it came out of all the research and reading I was doing. African folklore is just so lush. There’s something so relentless and sensual about African mythology. Those stranger elements aren’t about me trying to score edgy post-millennial points. They are old elements. A lot of this book was about taking quite freely from African folklore, specifically from the area below the Sahara Desert. And that’s important to me. Mostly when people think of sophisticated Africa, they think of Egypt. And even that they attribute to aliens.

ERDRICH: [Laughs] Everything indigenous was brought to us by an alien.

JAMES: Absolutely. Aliens clearly told the Mayans that a year is 365 days.

ERDRICH: Of course. Well, you drew from a wealth of world culture here. Did any particular characters, whether it’s Beowulf or the American cowboy or Thor, work as a kind of magic sieve?

JAMES: I don’t know. At one point, the book started to almost write itself. I spent two years researching it. I was researching it before I won the Booker Prize. There was a point where I was getting bogged down in the research, but I had a pretty clear idea of the story I wanted to tell. I knew the characters because they showed up in my head, sometimes years before I knew what their story would be. I was really interested in trying to find the pre-Christian, pre-Islam, original African religious Africa. That took quite a bit of digging, because when black people got thrust into the Americas, the aim, mostly, was to kill the African in us. But that didn’t quite succeed. Still, it was hard to access all the stuff on gender and identity and sexuality, especially because in a lot of African countries Africans believe what preachers on American television tell them. Evangelism came in and really did a number.

ERDRICH: So that kind of research was difficult to track down?

JAMES: It’s not hidden, but it’s just a lot of work to find. The problem, of course, is we have so much popular European literature and academic European history. We don’t have a lot of pop-African history or pop-indigenous history.

ERDRICH: Or we have anthropological accounts put through a wringer of fundamental Christianity.

JAMES: Absolutely. For example, I read so many of the African epics, which to me are on par with anything from Homer. The thing is, unlike Homer, they haven’t been translated by a poet yet. They’ve been translated by scientists, by archeologists, and so on. You get what they’re saying, but you don’t get the rhythm and bones and poetry and message and music.

“Being a black man in America, I literally do not know how to conduct myself in a public space. I don’t know how to meet people without it seeming intimidating. I don’t know if i should wear glasses, if I should try to look extra gay, if I should stand up, sit down, wave my ID, not reach for an ID. I don’t know.” —Marlon James

ERDRICH: I know you listen to music while you work. What were you listening to while writing this one?

JAMES: I was listening to a lot of Miles Davis, like Bitches Brew. In fact, I’d listen to music before I even got to work. I’d jump on my bike and put on “Spanish Key” for the ride to my office, which is in midtown Minneapolis. The headphones were on when I got off the bike and the headphones were still on when I sat down at the desk and turned on the laptop and wrote. Sometimes the music I want is not even music, it’s just noise. I open the window so I can hear traffic. A student of mine from India just wrote an essay in my class where he talks about how he finds noise and chaos comforting. I know exactly what he means. If you’re in Mumbai, or in Kingston or in New Orleans, you grow up in noise. I grew up in noise. I grew up in a big family. It’s not like everybody’s going to shut up so I can do my term paper.

ERDRICH: And you’ve chosen to live in one of the few noisy parts of Minneapolis.

JAMES: [Laughs] Yeah, the operative word being “choice.” It’s not like I read in noise. I read in quiet like everybody else. But I keep thinking there is some sort of energy, some sort of a rhythm, something I’m going to miss if I close the window. I think it feeds me in that way. Again, growing up in a noisy house in a noisy city, you just come to peace with noise and that adds to the musicality of it. Also, there’s the fact that a lot of epic folklore is written to be sung, and not just in Africa. A lot of ancient epics are written to be ballads. And as you’re speaking them you have rhythm. To me, writing to be read aloud is important. I still write that way.

ERDRICH: I think, too, for that kind of writing, the musicality helps with memory. Music helps you memorize. And these were oral traditions that were not written down for a long time, true?

JAMES: Most of them were still not written down — and certainly not written down by the people who were voicing these traditions. If I’m a French archeologist copying Sanjara, then no wonder people don’t know that’s the original story of The Lion King. In Mali, it’s a story of Sanjara, also known as Sundiata, and how he became king. Nowadays, people say, “The Lion King is from Hamlet.” I’m like, one, you need to brush up on your Shakespeare, and two, it’s not Hamlet, it’s a story of Sanjara, the Lion of Mali.

ERDRICH: There are epigraphs and aphorisms sprinkled throughout your book. They’re in a language that I wasn’t sure was invented or real.

JAMES: It’s kind of all of the above. One secret of the book I’ll let you in on is that I’ve hidden the translation for the African sayings usually three or four paragraphs down the page. The thing is, English is my language. It’s the language I grew up with and it’s the one I speak. But what I had to let go of here are the rules of English. I wasn’t going to do some imaginary exactitude of an African language — I wasn’t going to turn Wolof into “Elvish.”

ERDRICH: You weren’t going to invent a Klingon.

JAMES: Precisely. For example, in Wolof, verbs remain present tense, which I thought was really fascinating, because in Jamaican patois, verbs also stay in present tense, but we’ve always thought that was a sign of unsophisticated English. It turns out it’s not. The credit to African language is that the verb always stays present. It’s not, “he went,” it’s “he did go.” It’s not, “he’ll be going,” it’s “he soon go.” One of my characters always speaks in present tense.

ERDRICH: In all of your writing, there’s a sense that the reader is entering into a world with its own language and rules. The Book of Night Women and A Brief History of Seven Killings each had this feeling, too. I remember after we first met, I opened a book of yours and snapped it shut with such excitement thinking, “This is a world I’ve never been in.” By the end of Black Leopard, Red Wolf, I was getting so uneasy because the witches were getting hacked apart.

JAMES: This is a trilogy, and the witches’ story is the next book. Sogolon, one of the witches, tells the next book, and I think her perspective is going to be super interesting, if for no other reason than she’s 350 years old.

ERDRICH: You know, the last time I saw you, you were cooking for everybody — and the food was so good everyone was trying to be really civil and not grab away the last piece of lamb. Are you still cooking?

JAMES: Yes. Michael Pollan has influenced me. He said you only need to follow one diet rule: Eat whatever you want, just cook it yourself. So, Michael Pollan, I baked a Greek apple–and-brandy cake last weekend.

ERDRICH: I want that!

JAMES: I’m into cooking more than ever. I really appreciate the whole idea of cooking at home and inviting people over with food as a kind of communion.

ERDRICH: Where did you learn to cook?

JAMES: My father, mostly. My dad and my mom were very different. My mom taught me to cook to survive — the children need to eat, so learn to cook chicken — whereas my dad was very fussy. He’s like, “Here’s how you cook lamb, here’s how you cook crab, here’s how you cook lobster.” He could cook these fantastic dishes, but they weren’t very practical. I learned a lot of cooking before I was 12. I’m sure at 12 I was cooking four-course meals with lobster and crab and all sorts of mad stuff.

ERDRICH: That’s mad stuff for a person like me from North Dakota. [James laughs] You went back to Jamaica last June, right?

JAMES: Jamaica is really fantastic. When the last book came out, there were concerns about if I was safe there. I also had those concerns. Sometimes I ran into people who were thinly disguised in the book and I thought, “Oh, man, I’m going to die right now.” And instead they tell me they love the novel.

ERDRICH: I don’t want to call you a “political writer,” but I do think we are in a moment where black culture is being celebrated and dominating certain cultural arenas. In terms of literature, there’s you, Colson Whitehead, Jesmyn Ward, Zadie Smith, Roxane Gay, Tracy K. Smith—this long list of people who have just surged into world consciousness. But at the same time, there’s this tolerance of white supremacist terrorism — and state tolerance of it with these outrageous murders of black men by police. Why is this happening at the same time?

JAMES: Whether I like it or not, I’m aware of it at all times. I write about this in my Facebook posts. Being a big black man in America, I literally do not know how to conduct myself in a physical space. I don’t know how to meet people without it seeming intimidating. I don’t know if I should wear glasses, if I should try to look extra gay, if I should stand up, sit down, wave my ID, not reach for an ID. I don’t know. I am literally immobilized in the presence of a lot of police power. That is a reality that could cross any form of social class, because it’s racist. And it’s very Caribbean of me to think my class can exclude me from racism. It’s very Caribbean of me to think that if I just dress nicer, if I just wear a suit… It has nothing to do with that, it’s racism. But it’s not just extreme racism we should be talking about. It’s also the polite racism of liberalism. It’s the fact that liberalism and segregation exist wonderfully well. Minneapolis, Chicago, and New York have the most segregated schools in America. I think we still have this idea that systemic racism is some Southern thing, when it’s like, no, it’s everywhere and it’s a daily reality and something that I never lose sight of. I’m never allowed to lose sight of it. It’s thrust upon you whether you like it or not. It doesn’t matter if Jay-Z walks to the subway station, he can still be stopped and frisked. They don’t know who he is. These are the kinds of conversations that need to happen but don’t. I don’t think I’m an activist, and I don’t think I’m on a mission, but I think I’m a writer in the world, the world is always around me, and I’m always responding to it and living in it and having to come to terms with being in it. I don’t think you can escape that.

ERDRICH: I think a lot of what’s happening now is a result of the incredible racism that was generated by the idea that we could have a black president. And I think it always may have something to do with an uneasiness in realizing — I hate to say it — that there really isn’t a white culture. People in this country are clinging to the idea that there is something called white culture. And it actually doesn’t exist.

JAMES: No, there is no white culture. There’s Irish culture, there’s Polish culture, but there’s no such thing as white culture. And you know, we’ve all talked at length about white appropriation of culture. But I also find that there’s this idea out there that mediocre colored folk are coming for your stuff. You see it with so-called anti-PC writers when they hear there’s a scholarship for writers of color. Or when a publishing house puts out a press release saying they want their authors to reflect the larger world. People respond with, “Oh, we’re going into mediocre times in the interest of inclusivity and political correctness.” It always struck me that the simple assumption was that these people couldn’t be good. In the move to be more inclusive, it never occurred to them that these writers would be good. And with it, there’s this idea that this mediocre colored, queer, lesbian, native, non-English speaking poet is coming to take their spot, which I find way more fascinating than the arguments about political correctness. Why do you keep thinking people are coming for your shit? Nobody wants your spot. Nobody is going for your spot.

ERDRICH: That’s it, exactly. It’s this fear.

JAMES: It’s the same as in Charlottesville, saying, “Jews will not replace us.” Nobody’s trying to replace you. Why do you think you’re being replaced? Why do you think you’re being displaced? In history, Europeans did a lot of the displacing.

ERDRICH: I will say another thing I loved about your book is the space you gave to women characters. In so many of these adventure sagas, there just doesn’t seem to be a place for women.

JAMES: Right. You can almost call a lot of these adventure stories, “Will the men make it back alive?” stories. That’s pretty much what they are.

ERDRICH: A hero’s journey is always about a man. And there’s always some helpful maiden, or at least a maiden to rape on the way. That’s how these adventure stories go. That’s one of the reasons I got so excited about your witches being able to speak. Women have a murderous power here. Okay, so you must be doing a big tour for this book. Do you enjoy going on the road?

JAMES: Partly, just because I spent so many years in the entertainment industry when I was art directing for musicians like Sean Paul. [James worked for a decade as a graphic designer for a record label in Kingston.] I got used to the relentless touring. So to an extent, yeah, but eventually venues start to blur into each other and you realize it doesn’t matter how big you think you are, you are going to run into a reading where nobody shows up.

ERDRICH: That can’t happen to you.

JAMES: Of course it has. In Seattle, actually, a few years ago. But at the same time, one of my biggest readings ever was also in Seattle — on a Monday night when it was raining — so I can’t hold it against Seattle too much.

ERDRICH: I gave a reading at the beginning of my career during a tornado watch when everybody was supposed to stay underground. Nobody came. Well, I think I will end with asking you the kind of nice question Minnesotans tend to ask. How were your holidays?

JAMES: I was in New York where my family is. For New Year’s Eve, I was in the basement with my boyfriend, my best friend, and somebody I just met. We drank champagne and listened to Madonna’s “Holiday.”