Revenge of the Booed Opera

There is no redemption in the Napoleonic era in which Puccini’s Tosca is set. None of the main characters, with the significant exception of the villainous tyrant Scarpia, could be said to have earned his or her murder by deceit or suicide. This is not the experience of the Greek hero and his insurmountable fatal flaw; the eponymous protagonist, a singer, indulges in a bit of hysterical jealousy when she realizes that her lover, the painter Cavaradossi, has painted the Madonna after the sister of an escaped rebel. Cavarodossi, for his part, plays the martyr, and the easy token victim to conservative repression of Scarpia’s repressive regime.

But there was redemption Wednesday and Friday night in director Luc Bondy’s production of Tosca, a piece that was booed when it premiered almost a year ago. The show was roundly compared it to the storied production by Italian director Franco Zeffirelli, with Maria Callas in the lead part. (Zeffrielli, for his part, called Bondy a “third-rate” director for turning Puccini’s opera into a darker, more minimal affair).

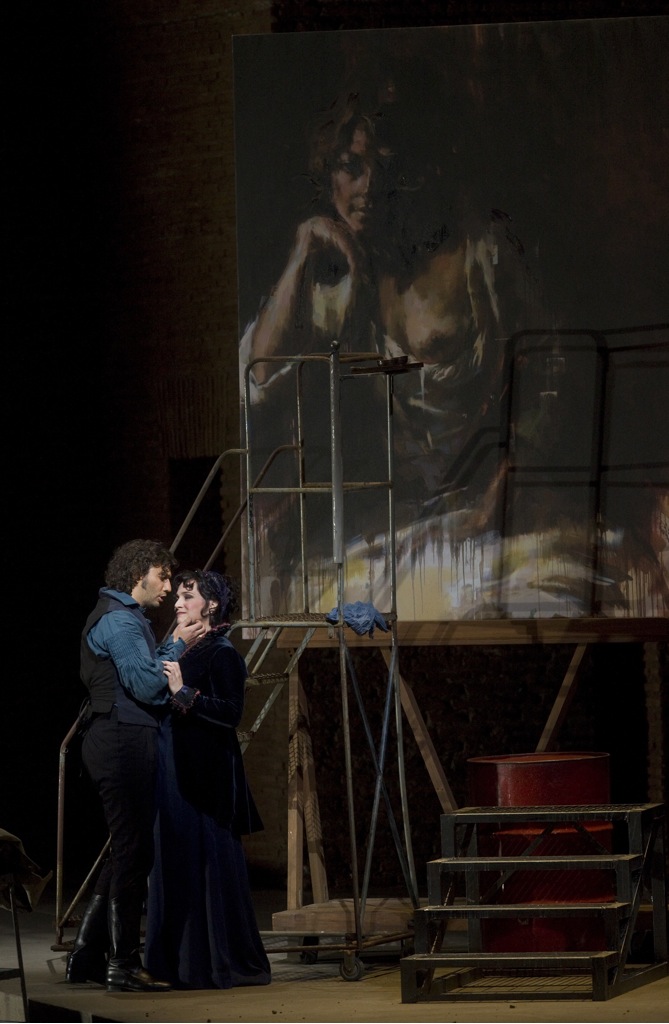

On Wednesday, Bondy set out with a new cast: Patricia Racette, in the role opera buffs (and all they do is polish) remember as belonging to Maria Callas. Racette is irascible and inexplicable with jealousy, and then melodramatically appeased in the first act. She’s tragic in the last, as her attempts to defend her lover’s honor, her honor, and then his life, are in vain. Although the script calls for vast changes in temperament, Racette’s style never feels episodic. She carries the lyrical arias in the second act, and her voice grows as the show goes on, pleading for Cavaradossi’s release as he refuses to give up the location of the hidden rebel. Racette’s a wise choice to supplement the public memory of Tosca because, like Callas, who could go dramatically flat, her’s is an idiosyncratic voice. She’s gravelly and her pacing is wild in the beginning, but unfolds and ultimately demonstrates control.

Jonas Kaufmann is rare for a German tenor–he’s smolderingly handsome. He’s also remarkably fluid as the strong-willed bohemian who sticks to his guns but can’t save himself–and maybe, just maybe will find vindication when Napoleon defeats Scarpia. His voice soaring over the orchestra in the first act was particularly remarkable. Bryn Terfel finds humor as the relentless Scarpia; he uses his strong baritone to overpower and seduce.

There are repeated complaints about the interpretation of staging, which are not, in fact, distracting. Cavaradossi’s painting of the Madeleine with her breast exposed is onstage throughout; it’s a sordid altarpiece in an opera with equally sordid motives. The booed production involved characters embracing this image; she’s only cut, here, across the eyes by Tosa, her innocence already lost. Thankfully, the production lacked the rising and falling sets and mysterious nooks that the Met so often favors. The second act, set in Scarpia’s chambers, the setting of the second act, was a wonderfully bizarre period room, which looked like an administrative post office designed by Frank Stella in the 1970s. It was as fully and obscurely realized, as an opera about unexplained wrath ought to be.