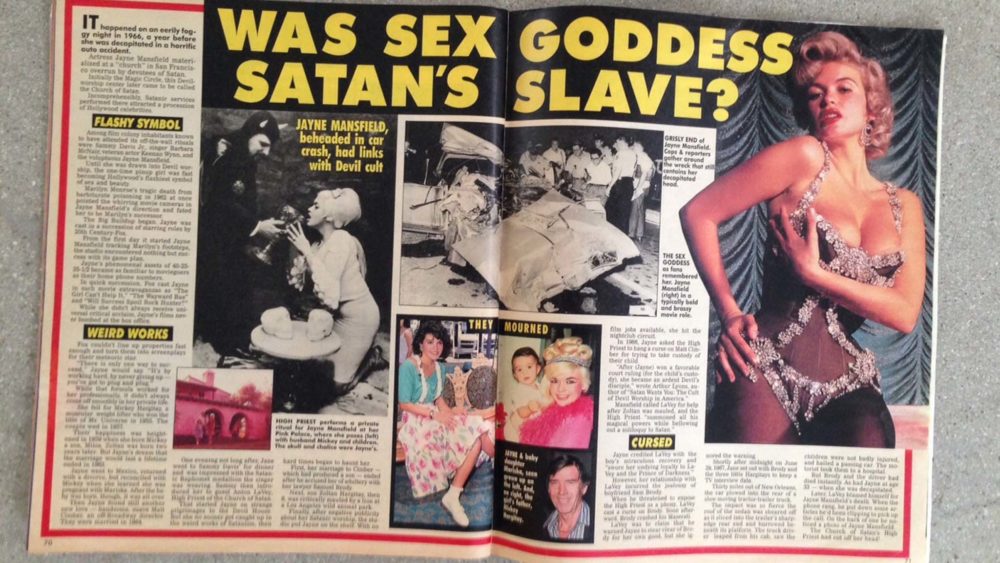

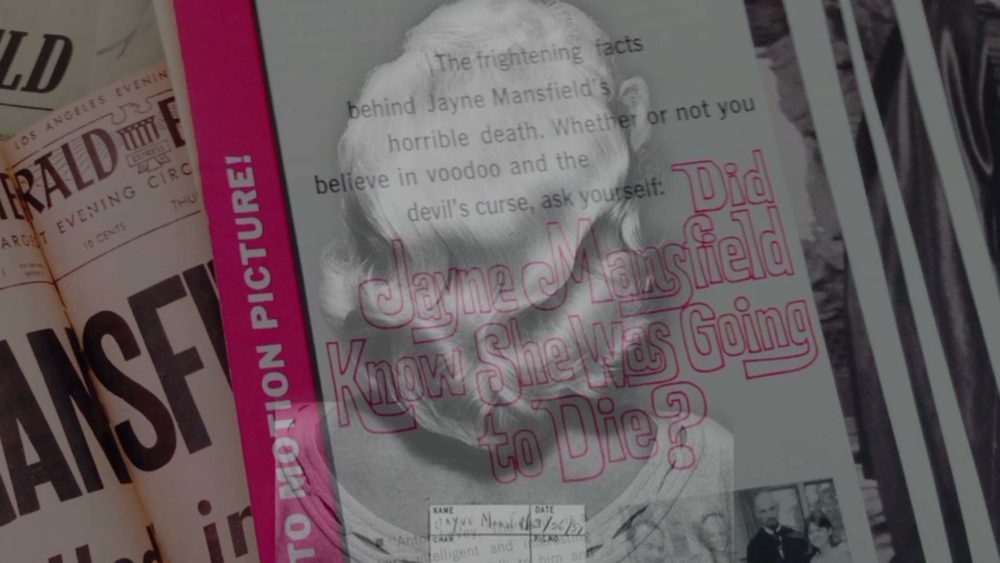

The secret history of Jayne Mansfield’s bizarre connection to the Church of Satan

“We had known this story for a long time,” recalls filmmaker Todd Hughes, “that Jayne Mansfield had flirted with Satanism, or so we thought—and that she was decapitated in a car crash, which turns out not to be true.”

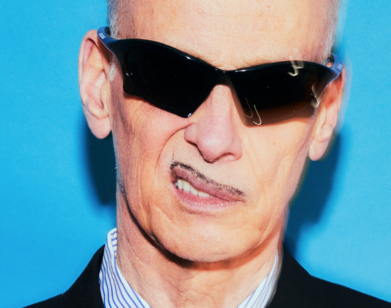

For Hughes and co-director P. David Ebersole, these long-circulating rumors served as jumping off points for their new documentary Mansfield 66/67. In the film, they examine the last two years of the Old Hollywood bombshell’s life by interlacing footage from films, interviews, and photo ops with press clippings and commentary from subversive director John Waters, experimental filmmaker Kenneth Anger, Warhol Factory star Mary Woronov, and Hitchcock actress Tippi Hendren, among others. It’s the myth that interests Hughes and Ebersole, rather than pinning down what actually transpired before Mansfield died in a fatal car crash at age 34.

Mansfield 66/67 tracks the bizarre and tragic events that occurred after the actress began associating with Anton LaVey, the high priest of the Church of Satan. After LaVey supposedly put a curse on Mansfield’s then-boyfriend, Sam Brody, her divorce attorney and de facto manager, a series of misfortunes beset them. Mansfield’s son Zoltan got mauled by a lion, and Brody was in a string of car accidents, with the couple and their driver dying in a horrific crash less than a year after meeting LaVey.

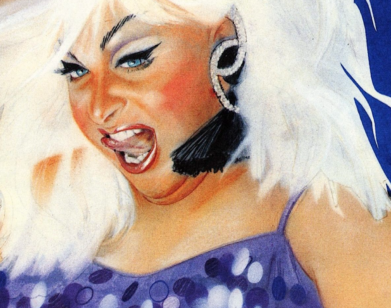

In the 1950s, Jayne Mansfield was groomed by Twentieth Century Fox to be their answer to Marilyn Monroe. After starring in the 1955 Broadway hit Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, Mansfield was named one of the most promising newcomers at the 1957 Golden Globe Awards for her breakthrough performance in the 1956 film The Girl Can’t Help It. For a brief time, she was a popular performer, playing mostly comic roles as a pneumatic blonde with an exaggerated and obvious appeal.

Hughes and Ebersole document how the tensions of the Cold War climate allowed Mansfield to become a sensation in the ’50s and how the radical cultural shift of the 1960s soon left Mansfield out of step with the times. The period leading up to her death was “just so peculiar,” Hughes muses, speaking from the Provincetown International Film Festival earlier this year. “Jayne was an anti-Vietnam activist, people were experimenting with drugs and questioning their faith. Time Magazine’s cover line asked, ‘Is God Dead?’”

The filmmakers believe that while Mansfield was indeed publicity-mad, she was also a very intelligent woman who was figuring out a way to support her five children and reckon with three ex-husbands.

“She crafted this phenomenal, larger-than-life movie star image in the ’50s that completely fell out of vogue,” says Ebersole. “In the ’60s, everyone wanted you to be real and down-to-earth. We always thought that’s part of why she got caught up in seeking. That’s part of why she found her way to the Church of Satan.”

LaVey, who painted his Victorian house in San Francisco black and wore outlandish costumes with plastic horns and a cape, was not a true, dictionary-definition Satanist—the Church of Satan, which he founded in 1966, does not believe in the Devil, or in the Christian or Islamic conception of Satan—but rather an inflammatory figure who espoused individualism, pleasure, and self-preservation. He drew aesthetic inspiration from horror films and The Munsters, and he established The Church of Satan, Inc. with a publicist in tow.

“Anton LaVey was like Hugh Hefner,” says Hughes. “He just used the word Satan to get attention, but his whole thing was about empowering people and rebuking Catholicism.” Ebersole adds that LaVey was also “important in what he represented—that ’60s self-enlightenment. Jayne was judged for her sexuality. He was saying, ‘Be yourself.’”

After meeting LaVey during a trip to the 1966 San Francisco Film Festival, Mansfield was intrigued. The unlikely pair were photographed at the downtown L.A. restaurant La Scala and at Mansfield’s pink palace by her heart-shaped pool. Though there are photos of LaVey performing Satanic rituals with Mansfield against a backdrop of tiger-skin rugs, the actress told reporters that she was Catholic and that she did not believe in his church, but that she regarded him as “a genius” and “an interesting person.” (As a duo, they call to mind Pamela Anderson and Julian Assange, another knockout beauty drawn to a man of obscure, forbidden knowledge.)

Anger—who is known for his interest in the occult and who cast LaVey in his 1969 film Invocation to My Demon Brother—doesn’t believe LaVey was a powerful enough magician to put a serious curse on someone and have it actually work. “Curses, smirches,” he declares in the film.

It is likely that the friendship between Mansfield and LaVey was, in large part, a publicity stunt, but the movie touches on what this odd couple had in common and why they could have been captivated by each other. Besides their unquenchable desire for publicity, they both had self-aware, tongue-in-cheek public personas that were connected to taboos about sexuality and self-expression.

Though Mansfield was seemingly at odds with the feminist movement—Ebersole counts his mother as one of the feminists of the time who would have viewed “the image of what Jayne Mansfield represents as anathema to women coming into their full selves”—today she might be embraced as a canny, sex-positive woman. Though, to use a phrase from a psychologist who appears in the documentary, the line she walked “between empowerment and exploitation,” was one that was decidedly unclear.

Hughes and Ebersole speculate that had she lived, Mansfield may have been rediscovered by arthouse auteurs like Fellini or American independent filmmakers, or perhaps by a transgressive artist like Waters. For her part, Mansfield emerges as a sympathetic figure. Near the end of the documentary, there’s an archival news clip in which Mansfield is asked, “How much longer do you think you can be a sex symbol?” Coolly, the actress, who was not yet in her mid-thirties, replies, “Forever, darling.” Regardless of whether her poise was partly a pose, you can’t help but admire her self-possession.

IMAGES COURTESY OF THE FILMMAKERS. MANSFIELD 66/67 IS NOW PLAYING IN SELECT THEATERS.