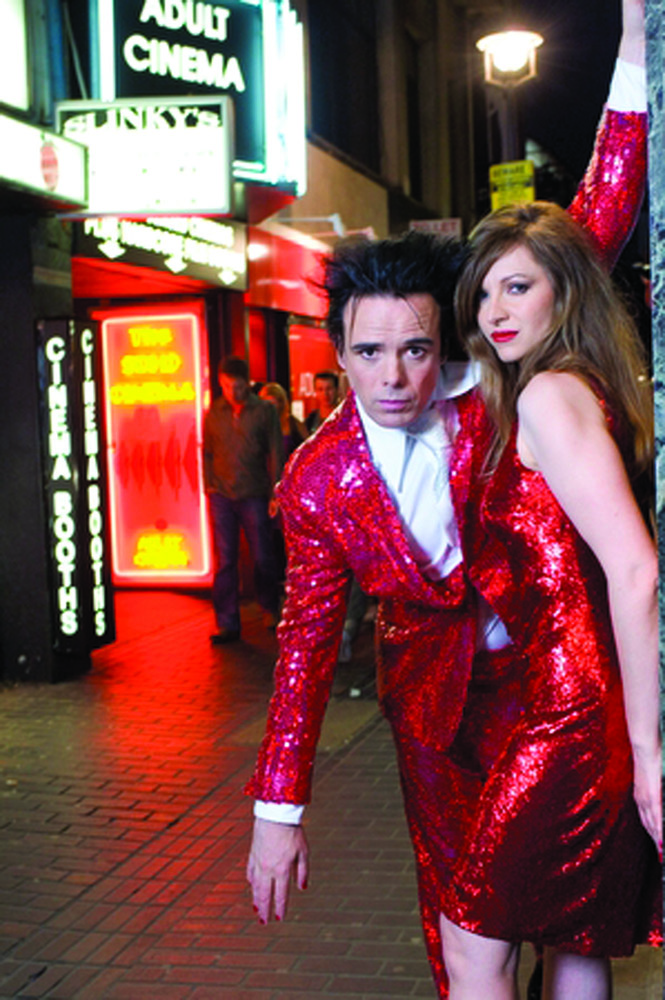

Sebastian Horsley

Sebastian Horsley’s recently published—and justly acclaimed—autobiography, Dandy in the Underworld, is a true story of love and drugs and clothes and marriage and money and gangsters and actually getting crucified to see what it’s like. He sometimes paints and sometimes doesn’t; he says this doesn’t matter really as he doesn’t have much talent. He talks a lot and writes magnificently about his greatest work of art, which is himself.

He lives in a tiny apartment in Soho, London, opposite his tailor John Pearse, which is useful as he believes if you have a good tailor, you don’t need a psychiatrist. He has a lot of suits and gloves and handmade ties, velour fedoras, and an umbrella or nine. The apartment contains the pictures on which he is not working, a shelfful of skulls, and a snub-nosed Colt .38. The decoration also includes the artist himself, who is shifting about the place with a stovepipe hat in one hand and an empty mug in the other.

Jessica Berens: Are you going to sit down?

Sebastian Horsley: No.

JB: God, I’m bored.

SH: You’re bored! I’m bored. I’ve been talking about myself for the last week.

JB: You’ve been talking about yourself all your life—at least now you’re being paid. I’m genuinely worried about what is going to happen to you when the publicity stops. Have you got a plan?

SH: I have no idea. Rest on my laurels until they become wreaths. The trouble is, I’m a one-trick phony. Shall I put my hat on?

JB: You can do what you like as long as you remember that nothing you do will impress me.

SH: [laughs] I think trying to impress someone and failing is quite a good look.

JB: Do you have to bend to go through the door in that hat?

SH: Yes.

JB: Have you been around Soho wearing it?

SH: Yes. Every day for the last three weeks.

JB: Do people take your photograph?

SH: Yeah. I do get photographed. It’s really interesting because 50 years ago, if you didn’t wear a hat everyone looked at you. It just proves that everything is fashion. I like it when people roll down the car window and go, “Fuck off, you fucking posh cunt.”

JB: It’s worth writing a second book just so that you can call it Posh Cunt.

SH: I’m not a posh cunt! I’m flash brash trash. If someone thinks I’m posh, it just shows how lowly they are. Some people think I went to Eton. I’m far too stupid to get into Eton.

JB: How old are you now?

SH: I’m not telling you.

The problem I’ve got is that I really like drugs SEBASTIAN HORSLEY

JB: You’re well over 40.

SH: Yeah, I’m 45. I had to go on a vegan diet after I got on the scales and they said, “Come back when you’re alone.” I was like 15 stone. Getting old is horrible, but it is interesting . . . one of the things I’ve realized is that growing old is compulsory, but growing up is optional. I will be a senile delinquent and overact. Anyway, I might be old, but I’m still desirable.

JB: Depending on how much cash you have on you. How are your finances, by the way?

SH: Well. Not quite so bad as they were. The pieces from the show [Horsley’s 2007 exhibition “Hookers, Dealers, Tailors”] sold £35,000.

JB: It didn’t! That’s great.

SH: I know. Unbelievable isn’t it?

JB: I thought it was very funny in your book when you drew attention to the fact that you had very little talent as a painter.

SH: Did you like that? Well, it’s true.

JB: I also liked the description of meeting Quentin Crisp. I had a similar experience.

SH: Do you know how much money he had in the bank when he died? Just over $600,000. Does that make him a miser or does that make him someone who didn’t want to change his life? My only criticism about Quentin Crisp is that the subversive must be ready to subvert themselves. I may dress for myself, but I undress for everybody else, whereas he never did that—he was never prepared to drop a bomb on everything he did.

JB: He was about being himself at a time when being a queen was actually dangerous. To undermine himself would have been to collude with all the people who had persecuted him.

SH: I saw him as a warrior and as a spiritual giant. His books are holy. He had incredible knowledge and wisdom. And he was a dandy. Everyone says Oscar Wilde was a dandy, but he wasn’t, he was an aesthete. He took pleasure in food and stuff like that. Dandyism is much more austere-much more Calvinistic, more neurotic—it oscillates between narcissism and neurosis.

JB: What are you going to say to the Americans? They are very politically correct.

SH: Oh fuck, another form of censorship. All the people I admire have stiffed in America—Marc Bolan, the Sex Pistols, Jarvis Cocker.

JB: Your affair with Hugo Guinness might entertain a few people. I particularly enjoyed the description that he was “incandescent with moral decay.”

SH: That bit is really written with tenderness. I didn’t want to upset him. He’s not litigious is he? Some of the weirdest people are. If I hear that people are litigious, I immediately dismiss them.

JB: Is it worse than being fat?

SH: I like fat girls. A woman can never be too poor or too fat. I’d take a poor fat girl over a rich thin girl like Kate Moss. She’s revolting. A woman is supposed to have curves like an old Bentley, not like some old bike. I wouldn’t take a ride on ‘er. I hate her and I hate the society that worships her and Pete Doherty. Pathetic, stupid, spineless, talentless, and potato-faced. There’s no moral content and it really annoys me, having grown up with people like Bacon and Beckett and Johnny Rotten. What happened to defiance? I think if you’re pissing off English people, you’re doing your job. I told you I met Johnny Rotten.

JB: Yeah. You said he was awful.

SH: It was so depressing.

JB: There’s a left-wing terminally jaded intelligentsia of urban America who might like you.

SH: I don’t really know what Americans are like. I’ve no idea. I know a few things about them. In my imagination, they have warm peachy hearts, whereas the English have horrible spiteful withered hearts—success in England inspires envy—in America, it inspires hope.

JB: You watch the television don’t you?

SH: Are they like that?

JB: They’re like Courtney Love.

SH: I don’t like ‘er. She’s awful. Are they like Madonna? She’s awful too. Perhaps someone will shoot me. Does it hurt, getting shot?

JB: You could get the PR people to organize it.

SH: To be worthy of assassination takes more than some crappy little book.

JB: How’s life off drugs?

SH: The problem I’ve got is that I really, really like drugs. I love everything about them. It is horrific being sober all the time-utterly awful. Then you realize that misery, once you get used to it, is as agreeable as happiness. It’s all right to be miserable. Perfect happiness is not obtainable, so by the same token, perfect misery is not obtainable. Do you think one of the ingredients of happiness is to be without something?

JB: I don’t think there is such a thing as happiness-it’s just a strange hormonal rush.

SH: People are obsessed by happiness, but there are a lot of other invigorating experiences available, aren’t there?

JB: What, like reading your book?

SH: I don’t think I’m known for my gifts—I’m known for my gall. I don’t want to be just a famous person—I’m too old. People say I’m like this because I want attention, but is that a criticism or praise? I am desperate for attention. But everyone else is too. Everyone has fantasies of fame and greatness. Life for most people is a process of shedding those fantasies. You want to be the person you’ve dreamed of being. I don’t know if it is true that I don’t care what anyone thinks. You either conceal who you are and hope to be accepted or you reveal who you are and risk rejection. I’ve always thought it was more interesting to be the second one. There’s a lot of noise about me that stops a lot of people from listening, but the good side is if you expose yourself like that, you’re left with only good people who can see through you-you get rid of all the wankers. It’s like weeding your social garden. People either hate me or dislike me—but I realized a couple of days ago that people aren’t against you, they are for themselves. We’re all prejudiced in favor of ourselves.

JB: Did I give you the line about deciding to give up living on account of the cost?

SH: You might have done. I think that’s mine. There’s so much nicked stuff in there. I like the half I nicked the best. I should have had the courage, really, and stolen the other fucking half. Plagiarism in every other profession is accepted—it’s accepted in music, it’s accepted in art. Damien Hirst is just Francis Bacon in 3-D. T.S. Eliot said that bad poets imitate, good poets steal. We steal and everyone shouts, “Plagiarist!” It’s just the transfer of bones from one graveyard to the other. And you can’t have a book that keeps saying “as so and so said.” That’s really naif.

JB: Have you been found out?

SH: I have covered myself by writing about it.

JB: Please don’t read. Oh, God. It’s worse than having to listen to poetry.

SH: [reading] Dandy in the Underworld is a dandy book therefore it must be true to dandyism where there is nothing false about inauthenticity just as there is nothing real about authenticity. It doesn’t make any difference. Dandyism is a celebration of life and a response to suffering-it’s also a lie. We build our character as a carapace to keep away the fear of the abyss. That’s what our character is for. Without language—without these so-called ideas—that aren’t even our own, we’re just a howling emptiness.