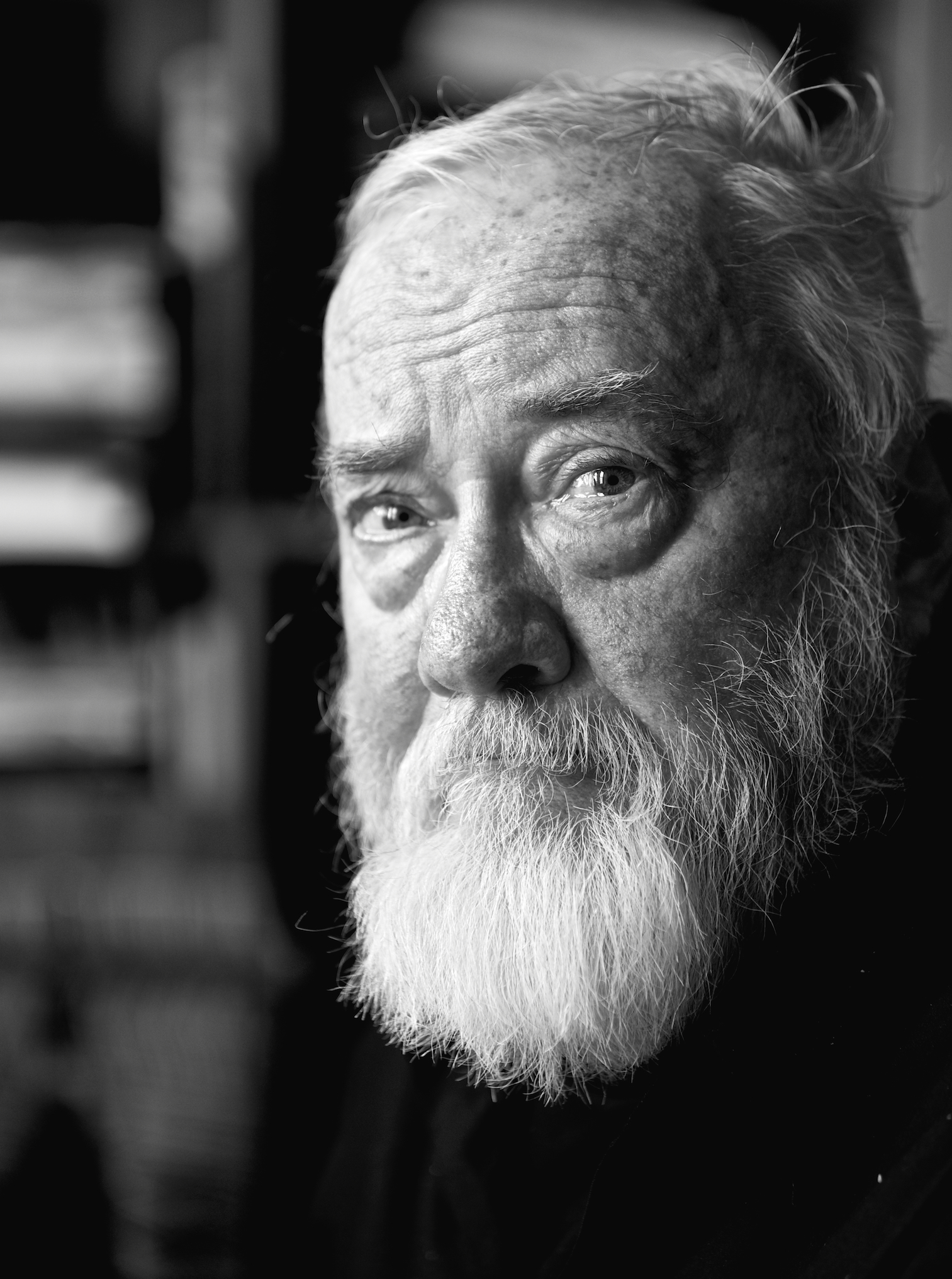

The Total Anti-Totalist Robert Stone

PHOTOS OF ROBERT STONE, ABOVE, BY FRANK SUN

Not far from 76-year-old novelist Robert Stone’s Upper East Side apartment is a model-toy shop. Its shelves are filled with miniature weaponized planes and ships that run the gamut of technological advancement through the United States’ various 20th-century wars. Throughout Stone’s long career as a premiere voice of American reason and delirium, his novels have brought many of those conflicts home in hallucinogenic, lightning-quick prose, in precise, haunting episodes, and in characters who appear like survivalists extended to the end of their tethers. Whether transporting Vietnam to drug-fueled Southern California in his classic 1974 novel Dog Soldiers or taking readers into the dark revolution of a Central American nation teetering on the brink in his 1981 novel A Flag for Sunrise, Stone is a writer with a preternatural ability to transform a location into a geo-political snare trap through which very few pass without a lot of pain or bloodshed. It is in many ways surprising that the writer came of age in the hippie Ken Kesey days of ’60s merry enchantment.

Stone’s masterpieces are thrilling reads, but they are never easy going; the ground, so intensely described, is always capable of shifting at the reader’s feet. Characters are driven by a volatile psychic compression of personal demons, ideological convictions, and social forces beyond their control. He is a complicated literary realist in that what is real is so often the least dependable place of all. In this sense, Stone is, perhaps, the most honest living writer America has.

His latest novel, Death of the Black-Haired Girl (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt), out this week, might sound like a murder mystery; but, in effect, the title serves to push the plot aside in favor of a deeper focus—not who did it or how, but what remains and what is lost after the body is taken to the morgue. The dead, black-haired girl in question is Maud Stack, an attractive, reckless, overconfident student attending an elite college in an otherwise depressed New England mill town; Maud not only pens an ugly op-ed for the school paper attacking religious anti-abortion activists but is involved with a married, middle-aged professor, Steven Brookman. Stone turns the college town into an unflinching crucible of class and generational warfare—and all of those 20th-century systems of ideology spelled out so carefully in his previous books make way for a 21st-century penchant for personal irresponsibility and fast forms of love and engagement. By the time the novel fulfills its titular promise, characters swerve between saving what they have and trying to make sense of whatever higher obligations keep them from sinking into the quick. Stone’s truths are hardly comforting—there is no pull of the thread that releases the knot—but if there is redemption in these pages, it is marked by those outside the wiles of academia willing to look the hard facts in the face.

I visited Stone at his apartment in early November. He was just getting over a cold. We spoke for an hour about his journeyman style of writing, and how the world turns just a bit differently than it did in his early days.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: I know when you were young, you were a pretty serious smoker.

ROBERT STONE: I’ll tell you a cautionary tale. I quit in the early ’80s. I came down with really serious emphysema just a few years ago and I quit in the early ‘80s.

BOLLEN: How extreme of a smoker were you?

STONE: I smoked about three packs a day. So that was a lot.

BOLLEN: Did you smoke when you wrote? Because when a habit burrows its way into your writing process, it’s very hard to weed it out.

STONE: The reason I was able to quit was because of the computer. You couldn’t lean a cigarette on a computer, like you could on a typewriter. So it just made it that much more difficult to smoke. So I quit. But this is now 30 years ago that I quit, and it still didn’t help me.

BOLLEN: Maybe the emphysema was due to the chemicals you were breathing during your time in the army?

STONE: I was in Naval Amphibious Force when I was a kid. They put us through all sorts of maneuvers that involved smoke screens. So it is conceivable. I would like to think I got it in a more heroic mode, in the service of the public. But I’m afraid that’s not it. I’m afraid it was just smoking, non-stop.

BOLLEN: Well, if smoking was in the service of your early books, that’s still heroic. Or maybe I’m just glamorizing the costs.

STONE: That was an upside. That is glamorizing it, but I’ll take it. [laughs]

BOLLEN: I always think of you as a master of location. Your novels dig into a specific setting and find the conflicting power dynamics and social forces that compose a hostile place. I’m curious why you chose the university setting for Death of the Black-Haired Girl. What intrigued you about the culture of a college town?

STONE: I’ve been a writer in residence for a lot of places. I’ve never had tenure anywhere, but I’ve taught all over—from the University of Hawaii to the Ivy League. I’ve observed a lot of that dynamic and decided I would employ it. It is a big issue, this abortion topic, which is yet another aspect of town-gown hostilities. And I wanted to bring in the character of Jo, one of my favorite characters who I kind of resuscitated from an earlier book. I wanted to use her and her perspective. And I wanted to use the controversy over abortion—that war that was going on. It seemed to characterize the university to me. The university campus isn’t my usual stomping ground, but I wanted to discuss it from various perspectives.

BOLLEN: In a small university town, there is class warfare and generational warfare. There’s an industry of privilege erected on top of a dying mill town. And even the motto of your fictional university has to do with eradicating Algonquin Native Americans through the eternal fire of enlightenment. So there’s an ethos about taking over the environment, the community.

STONE: It’s all gone completely haywire.

BOLLEN: When I think of your early book Dog Soldiers, you describe youths of the time so perfectly. But those youths are countercultural misfits in Southern California during Vietnam. The main character of the new book, Maud Stack, is a different variety of youth. She’s confident, educated, self-obsessed, self-righteous. Do you think those two generations of young people are dramatically different, then and now?

STONE: Very different. She’s a very different than a kid of the ’60s or ’70s. I’ve had my eye on kids since I have been teaching and have had several generations of children and grandchildren. I haven’t been that removed from them. But the ways in which Maud is different I think were less deliberate than they were just observed. I didn’t set out to define differences in these generations. I think they just emerged. She has an arrogance that the kids of the earlier age really hadn’t developed yet. It’s a matter of confidence, arrogance, and certainty. Our generation had that feeling of certainty, but in a way there was something that was skeptical about it. We didn’t 100 percent believe what they were saying.

BOLLEN: Maybe the difference lies in belief systems. There’s a line at the end of Death of the Black-Haired Girl l that I feel is the key to the entire book. It’s when Jo Carr, a nun, is talking to Victor Lerner, a psychologist. You write, “Their bond was that they both attempted to subscribe to some of the totalist metaphysical fantasies that had thrived in the previous century.” Is the heart of this novel the fact that the “totalist metaphysical fantasies” of the 20th century have all been destroyed?

STONE: Absolutely. Whether it’s Freud, whether it’s Marx, whether it’s any kind of totalism. I can’t remember who it was that coined the word totalism. It was one of the great intellectuals of the ’30s or ’40s. What he was talking about was essentially Hegelism—the inner content of history that the totalists believed in. People no longer believe in totalism, which I think is entirely a good thing. They lead to horror shows of all kinds and they’re disappearing, I hope. God knows, they may be replaced by something worse. But I think they are disappearing, and I think that part of this much decried “failing attention span” is responsible for it. Which makes it a good thing.

BOLLEN: So you’re in favor of the short attention span to prevent any cult of ideology?

STONE: In general, I would say yes.

BOLLEN: Which is probably why those students who attend Ivy League schools and presumably still have decent attention spans are so often the ones who fall pray to Marxism or left-wing extremism in the name of revolution.

STONE: They’re the last to persist in that school of education, within the necessity for history to have an inner core that can be resolved. They’re not really buying that, but their professors are. I think most people under a certain age would absolutely deny being a Marxist, or a Marxist-Leninist or a Post-Marxist or a Post-Marxist-Leninist. You have to go somewhere like the New Left Review to really even see the jargon anymore.

BOLLEN: When I started Death of the Black-Haired Girl, I thought it might be a murder mystery. But really it’s a slide of characters, where the attention turns from the catalysts—Maud and Steven Brookman, the professor she is having an affair with—to the survivors and witnesses, namely Maud’s father, Eddie, and Jo Carr. Do you realize when you begin a book which characters are going to overtake the others? Or is it a matter of which ones keep offering you interesting opportunities?

STONE: Maud’s father and Jo become tremendously important characters, and I didn’t know that was going to happen. I didn’t really know that Brookman was going to turn out to be such a self-indulgent asshole as he did, and really undeserving of his wife, who is a bit of a flake herself. But, yes, the key characters are really Eddie Stack and Jo. That developed during the writing. That’s often the case with a book of mine, and that was the case here.

BOLLEN: I think that’s why setting seems to be such an essential ingredient to your books. The place does a lot of the telling. Take A Flag for Sunrise, about a fictional Central American country on the eve of a revolution that is very similar to Nicaragua. Were you traveling through Central America in the late ’70s?

STONE: I went when Somoza was still in charge of Nicaragua. I went to go diving, because I used to do a lot of that. And I went to the Bay Islands before the cocaine boom, when it was a relatively innocent place. I was really very naïve about Central America, but I traveled there and met various people who explained the situation to me.

BOLLEN: This was right after you wrote Dog Soldiers. Were you consciously on the hunt for a new location to set a book?

STONE: Sort of. And this was certainly a good place for one. I got an offer of a ride from Honduras to Managua when Samoza was still in charge. I rode with the military attaché and his wife and his sister-in-law.

BOLLEN: A drive like that takes place in A Flag for Sunrise.

STONE: Exactly.

BOLLEN: That must have been an eye-opener. Did you sense the upheaval that was on its way?

STONE: It wasn’t happening yet. It was about to happen. People knew it was happening, and you could feel it, you could even hear little bits of it. The first thing that impressed me was that people were very frightened. And when they got scared, I got scared. I could see that really bad things were going to happen, and there’s nothing to stimulate a novel like a sense of general fear and paranoia. So that really kicked it off.

BOLLEN: I could just be speaking from the future here, but what’s exciting about a book like A Flag for Sunrise coming out in the ’80s, is that it seems to me that the esteemed American novels of that era are steeped in more internal, national fare—particularly regarding money and wealth and disaffectedness and urban class structures. You were carrying on this idea of the global from the success of Dog Solider into the ’80s with the crisis of Nicaragua. Did you find literature was less accommodating of that kind of larger-perspective book in the ’80s?

STONE: I thought it was exciting. I liked doing the locales. I love doing foreign cities, alien places, that’s something I just enjoy. And it was part of a world struggle when you have the deterioration of Reaganism into Bushism, you could kind of see the blindness, the failure to cope, and that impressed me—even more than the failure to cope at home. If I had been a truly political writer, I would have confined myself to the situation at home, but because I was really into having fun and writing global novels, I took the situation abroad.

BOLLEN: Did you find that other writers were doing that, as well?

STONE: Other writers I think were certainly beginning to do it. Norman Rush was beginning to do it, and then you had British writers who were doing it, like William Boyd. I was aware of their work, but I can’t say I was reading it at the time. I always knew I hated Graham Greene, even though I thought he was a really good writer. I really disliked him. My feeling as an American towards Graham Greene was absolutely mutual. [laughs]

BOLLEN: There’s a scene in Dog Soldiers in which a character named Gerald wants to try heroin because he’s a writer and his ambition is to write about the “drug scene.” The main character of the book ends up shooting him up right in the vein as punishment, and Gerald basically collapses and dies because of it. I thought this episode in the book might have been a shot across the bow for you. Like you were warning other writers who were pretending they could write about the dark, drug culture, “Don’t pretend you know the inside of the situation like I do.”

STONE: It was a gag on me.

BOLLEN: On you? I thought it was you claiming your territory against literary interlopers.

STONE: Well, that was the kind of message, but it was really a shot across my own bow. I was really making fun of myself.

BOLLEN: It doesn’t end well for you, then. You’re on the floor of a shack with no pulse.

STONE: When we were working on the movie adaptation, I kept insisting to [director] Karel Reisz that, no, he’s not really dead. Reisz said, “You could have fooled me.”

BOLLEN: When you’re writing about a place or a group, do you stick to situations you’ve researched or heard have happened? Or do you give yourself unlimited freedom to tell any kind of story you like?

STONE: I often try to use things that have happened to somebody that I’ve heard about or things that have actually taken place. I certainly did that in Damascus Gate. A lot of what happens in Damascus Gate really happened. It really took place. I used a fair amount of history and contemporary information. There’s a lot of stuff in Damascus Gate that is either historically true or was based on actual plots to blow up the temple.

BOLLEN: Did you go to Jerusalem for research?

STONE: I hung around with Israeli liberals, Israeli peaceniks, the liberal element of the Israeli left who are activists and who really knew what was going on. I hung out in the café, which is no longer, unfortunately, there, called the Atara in West Jerusalem where everybody would sit all day and talk about the situation. I got a residency in the city of Jerusalem at a really beautiful old Ottoman castle that they made available for a while to writers. But what sent me over there was actually an assignment from Esquire to do a piece on the Middle East. Most of the time I was in the Egyptian desert, in Sinai, having a fantastic time.

BOLLEN: It’s so beautiful there. I spent some time in Sinai three years ago. The sunrises are out of the world.

STONE: If you go up the ledge in Sinai, you get this red rock, this sunrise, and you never, ever forget it. It’s like you’ve seen a piece of paradise. So that was a wonderful assignment, and I spent a lot of time in Egypt and I passed very quickly through Jerusalem. The Israelis were just withdrawing from Sinai then. They had taken over all of Sinai, not just Gaza. We ended up caught in the riot in the Second Intifada, and we almost got killed. The guides that we’d been with, who were Israelis, gave us notes to the Israeli border guards, but it took us forever to get through the Egyptian army lines because, of course, that’s the most pompous part of the Egyptian bureaucracy. They finally let us through. And what happens is when you get to the Israeli side, you come through the squalor of the Israeli army camp and you come to the Israeli border and this great big beautiful air-conditioned bus comes and picks you up. It’s a bit like the border at Tijuana.

BOLLEN: Who were the writers that were major influences for you early on?

STONE: I was under the influence of the early modern masters, Fitzgerald and Steinbeck and Hemingway, especially, when I was a kid. I reacted against writers like Barth and John Hawkes. I did not care for the post-modernist stuff; my allegiance was to realism. I loved Dos Passos when I was younger. When I was at Stanford, there was a great passion for Revolutionary Road, which was an old-fashioned realist novel. There was something like a feeling like, my god, you know, the realist novels are something. What I didn’t understand in those days was the difference between realism and what wasn’t realism.

BOLLEN: I’m still often confused by the distinction.

STONE: Utterly confused. But we really were enthusiastic about Yates and Revolutionary Road.

BOLLEN: You found that realism was where you wanted to make your mark?

STONE: Basically, yes. I cast those distinctions aside. I did a lot of work that isn’t realist, that can’t be called realist….

BOLLEN: Your work is hallucinogenic.

STONE: Exactly. But I felt, to be grounded in realism and to go from there into the hallucinogenic, into what was not realism, was the way to do it.

BOLLEN: It’s interesting to think of Kerouac. Is that realism? Or the polar opposite?

STONE: I don’t know. I’ve never been a Kerouac fan.

BOLLEN: I know you aren’t. Although you did surround yourself with some of his associates. He must have been in the air around you at that time, whether you breathed it or not.

STONE: It was a funny situation, because I was in the service. My mother, who was a really strange person, sent me On the Road. Not too many people were sent On the Road by their mother, but I was. She said, “You have to read this.” It was more of her generation in a way, and I liked it because I was a teenager and I was in the Navy, for god’s sake. People were yelling at me and oppressing me. I was thinking, what could be more square?

BOLLEN: Why did you choose to go into the Navy?

STONE: I wanted to go to sea. I was romantic about the sea, and I wanted to see the world. Corny old Navy stuff. And I was not successful in school. I was not a good student. I was in a Catholic school, I did not get on with the order. I was very unfair to them, I realize now. I look back with regret with the way I mistreated them. I thought they were mistreating me, but I realize now that I was mistreating them. So I dropped out of school and I went into the service. My mother and I, we had zero money. We were living together in this hotel room in the middle of New York, the Chesterfield Hotel on 46th Street. We have this very odd familial relationship. Maybe not odd in any biological way, just odd socially.

BOLLEN: I just read that the poet Marianne Moore slept with her mother in the same bed until her mother’s death when Marianne Moore was nearly 50.

STONE: It’s the innocence of Marianne Moore, and the eccentricity. Well, my mother and I weren’t sleeping in the same bed, but we were in the same room.

BOLLEN: I like that your mother was okay with you dropping out of school and gave you a copy of On the Road. Were you a voracious reader when you entered the Navy? You must have shared books on the ship?

STONE: Absolutely. There were always people that you ran into in the service. Especially in the Navy, for some reason, always on the Amphibs. Those huge ships, you always found people who had read the same books that you did. There was always somebody on the ship who had read The Great Gatsby or had read Hemingway. You always found people to hang with.

BOLLEN: So that was an education?

STONE: Yeah. They were people whose history was like mine. They had been busted for stealing hubcaps, their father was in prison, and their mother was living alone, something like that. So I actually had a pretty good time in the Navy. I can’t say that I had a bad time.

BOLLEN: What year did you get out?

STONE: ’58.

BOLLEN: Did you come back to New York?

STONE: Yeah, I came back to New York and went to NYU. I had a really good freshman English teacher, who suggested the Stegner Fellowship at Stanford in California. I had grown up in New York, I had been a couple of places, I had been to Boston. But California was an utterly different world to me. It was like a garden without a snake. It had snakes, but I didn’t know about them at first.

BOLLEN: You were arriving in California at the right time.

STONE: Oh, I was lucky.

BOLLEN: Did you get involved in the whole Lawrence Ferlinghetti scene?

STONE: I didn’t know Ferlinghetti. Ferlinghetti was a lot older than I was. And Kerouac was older, this was a somewhat older generation. [Ken] Kesey was my age. Neal Cassady was a little older, but Neal Cassady liked hanging with Kesey. Neal Cassady was looking for the latest scene. I got out there in ’62. We were beginning to take acid. It was like the first acid generation.

BOLLEN: Did you seek this out, or was it around you at Stanford?

STONE: It was around. I just fell in with certain people who said, “You gotta try this stuff, peyote,” and I had never done it and I thought well, sure. [laughs] Woo! God. What a day that was.

BOLLEN: Do you think that those hallucinogenic experiences informed your writing? For example, the scene at the end of Dog Soldiers is filled with ecstasy and agony and mind-warps.

STONE: Yes.

BOLLEN: In college, I used to think you could split the population of the world into two categories—people who had tried LSD and those who hadn’t. Because once you try it, you realize that the entire world is basically chemicals in your brain—religious chemicals. Well, that was a while ago. It’s been years since I’ve done LSD.

STONE: Me too. But yes. You would say if somebody were coming to a party, “Are they cool?” You were mainly talking about dope, just about smoking dope. But you had to know, are they cool or are they going to be shocked out of their senses that people are doing drugs at this party? But that was the division among the literary or humanist students at Stanford. Are they cool or are they not?

BOLLEN: You were part of that world, but you have a rare career in that you moved beyond it. A lot of those writers fell victims to their own excesses, or kept repeating themselves. You managed to move outside of it—beyond the prankster van. How?

STONE: I really, really wanted to write. I loved language. I loved literature. I loved reading. I never read a foreign language, I’m afraid, but I loved Flaubert. I loved the 19th-century classics. I love Thomas Hardy. I wanted to be a goof on a bus, but I wanted to write more.

BOLLEN: Did you use a typewriter or did you write in longhand for your first book?

STONE: I was a radioman when I first went into the Navy, so I learned to type by taking Morse code. So I was using the typewriter from day one. My handwriting wasn’t any good anyway.

BOLLEN: Morse code is a strange system that I don’t think anyone in my generation understands. It’s extinct. It’s something you learn and read about constantly, but I don’t have the slightest idea what three dots and a dash means.

STONE: It’s funny, every once in a while I swear I’m hearing it and I think it must be a hallucination.

BOLLEN: Maud Stack is a character without any sort of nostalgia. As is her roommate, an actress. I feel for a long time young people have had a nostalgia about the ’60s and ’70s, but maybe that’s gone from the young now.

STONE: It’s gone. Those hopes, I think, they’re gone. Every once in a while, you get some kid who thinks Occupy Wall Street is going to bring it back. It’s not going to happen.

BOLLEN: You don’t think so?

STONE: I really don’t, just because the degree to which it’s occupied with totalism. Some people see the hope to restore Marxism and Occupy Wall Street, anti-capitalism. What can you do about capitalism? Capitalism is with us. If we don’t have debt, we don’t have the business society that we have, which is hateful. But life is shit. What’re you going to do?

BOLLEN: It’s like Nicaragua. If you go there today, it’s extremely poor and yet the government is trying to promote American tourism to its beaches. It seems like history went the long way to arrive at a rather sad place. Maybe American capitalism was always going to happen. I don’t know.

STONE: They don’t know either. But it is the only country in the world where you get to swim in a lake with sharks.

BOLLEN: I swam in that lake! Do you still travel?

STONE: Well, I can’t travel as much. I really have bad emphysema, I’m afraid. It keeps me from getting around. You know, I can do things. I’m reduced to situations where I take cruises, because I don’t have to walk very far and I like being at sea.

BOLLEN: Your 1992 novel Outerbridge Reach is about sailing, being at sea. How did you learn the sailing lingo? Was that from your time in the navy? You have a great ear for authentic dialogue.

STONE: I had a couple of advisors. One was the guy who designed a boat in the World Cup competition and who keeps a boat at Darien, a real, kind of an independent Canadian. And I’m a pretty quick study, and I do sail a little. Maybe I could get across Long Island Sound as a lone sailor. I’m afraid the scope of the earth is beyond me. I might make it to Port Jefferson. That would be an accomplishment. I’m not an accomplished sailor. I did pick up the lingo and I did work at it. My other advisor was Peter Davis, the documentary filmmaker. So from my two experts, my documentary filmmaker and my lone sailor, I had advice that I cultivated.

BOLLEN: Do you always seek out advisors for subjects? Or do you ever fact-check your books? Damascus Gate possessed a lot of details to double check.

STONE: I live in dread, because I don’t fact-check. I mean, I went to dinner at the consulate. There’s nothing like going to dinner at the consulate. It’s just great. You hear everything. Everybody talks. And going to dinner at the consulate, I once saw the two consulates in Jerusalem—one on the east side, one on the west side. Just talking to the reporters and the people who were there are mostly the press, so you just pick up enormous amounts of scuttlebutt. And hanging out at the Atara Café and just being introduced to people—the Israelis are very voluble and they like to talk. And the Arabs, too. So you learn a lot.

BOLLEN: But what’s interesting about Damascus Gate—and most all of the novels—is that you’re picking hot zones that people have very strong opinions about. Do you ever get a reaction on it? Or are you trying to be fair to all in the writing?

STONE: I try very hard to be fair, and I look for ironies. In a way, I live on ironies as a novelist. One critic from the Times picked up on a moment in the book where I say, “People look at Gaza and they say, ‘This is the equivalent of Auschwitz. This is the payoff for Auschwitz.’ How wrong is that, to say that what happens in Gaza could ever be the equivalent or the payoff for what happened in Auschwitz?” So what do I get in the Times? “Stone says that what happens in Gaza is the payoff for what happened in Auschwitz.” I’m not going to sit down and knock myself out writing a letter saying, “Hey man, read the thing straight.”

BOLLEN: It’s always bad when the writer responds to the critic. It never ends well.

STONE: I’ve got some pretty mean reviews in my time. Some are really, really mean reviews. I don’t let them hurt me anymore. Some people just don’t like what I do. I have to face that fact. They just don’t like it. [laughs] What are you going to do?

BOLLEN: Maybe that attitude is why you’ve managed such a long career. You aren’t writing for the critic. Maybe you’d have stuck to writing about Southern California druggies if you listened to the advisors of the day.

STONE: Right, and I think that helped me. Maybe it also helped that I’m not a very famous writer.

BOLLEN: Come on, yes you are.

STONE: Well, I have felt that I’m not risking my life and fortune and “Oh my god, this is going to be it.” I think I long ago reached the point where I’m going do it and I’m going to do the best I can and I’m going to try and enjoy doing it. If I’m not enjoying doing it…

BOLLEN: After your first novel A Hall of Mirrors came out in 1966, how did you get to Vietnam to start the groundwork for Dog Solders?

STONE: I was young enough and I went to England. For some crazy reason I went to Europe and I was batting around Europe. I shouldn’t have done that. That was not a good career move. I was doing more hanging out, more goofing, I don’t know what I was trying to escape after the first book came out, then I had to do yet more goofing around. But then I knew I had to go to Vietnam.

BOLLEN: And you were in Vietnam as a reporter?

STONE: Yeah, for an English magazine called Ink. That was the only way I could get there. And I wanted to. That was deliberate, premeditated—”I gotta go. I gotta see this.”

BOLLEN: I’m still trying to get a copy of Who Will Stop the Rain?, the film based on Dog Soldiers. And A Hall of Mirrors was made into a film too, wasn’t it?

STONE: Yes, and that one of the most horrible movies you can conceive. Conceive the most horrible movie you can and you’ve more or less got it.

BOLLEN: Why is it so bad?

STONE: I could say that all the reasons that it was bad have to do with other people, and all the reasons it’s good have to do with me. The director was Stuart Rosenberg. I always felt bad about [Paul] Newman, because Newman was a friend of mine and he really was a good guy. I miss him a lot. It was a bad movie and he was in it, and I felt partly the fault was mine. But the writer is of absolutely no consequence around a movie. They changed my script at whim, ad hoc, ad lib. It was awful. It was a terrible experience, and I was also very young. This was another part of my bad-good fortune. The movies were changing. It was Charlie Manson time. The movies were changing. They were using bad language. The crews were shocked. The makeup girls, the grips, were shocked at the language we used. They were shocked at the presence of hippie-dip characters like me wandering around set with their friends. My secretary would be shocked by people calling me up at the studio and saying, “Could you connect me with Mr. Stone’s office?” And she goes, “Just a moment, please.” [laughs] My friends thought it was such a riot that they could call up a Hollywood studio and ask for me. It was really ridiculous, but it was the changing of the movies. The movies at that time—this is the late ’60s, beginning of the ’70s—they were clueless. They had no idea what their audience wanted to see. They had no idea. They were trying anything. They thought there was this hippie stuff so they would try to do that by dressing extras in weird clothes. Oh, it was just absolutely pathetic.

BOLLEN: Did it get bad reviews?

STONE: [laughs] Pauline Kael probably wrote the most eloquent bad review she ever wrote about any movie over that movie. Oh god. It was awful. That was the first one.

BOLLEN: Finally, you use Catholicism repeatedly as a subject in your books. You were raised Catholic, and so was I. I’ve personally noticed that a lot of Catholics who fall away from the church when they’re younger return to it later in life. Do you find that you’ve changed on the subject of religion over your life?

STONE: Yeah, very much. I think that the element of whatever you want to call faith doesn’t really attach to doctrine or dogma or spiritual entities like Father, Son and Holy Ghost. I think there’s a necessity for some attachment to the spiritual world and, in a way, people really have to have it. They come back to it through whatever liturgical or non-liturgical means that they require. I think people are drawn back to it and I think it’s understandable. It’s not at all regrettable or regressive. I think it’s the way it is.

BOLLEN: At the end of Death of the Black-Haired Girl, there’s this very sad scene in which Eddie Stack tries to bury his daughter’s ashes in the same crypt as his wife, but the Catholic Church won’t allow it because of her stance on abortion. Did you see that as the cruelty of the Church, its inability to offer consolation or its narrow understanding of its service to the community?

STONE: It’s a problem with the church. That just came from my general disgust for the mediocrity of the Church, to which I once committed my spiritual life, and its intense mediocrity and utter failure. That’s where that came from.

DEATH OF THE BLACK-HAIRED GIRL IS OUT TODAY.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS THE EDITOR AT LARGE OF INTERVIEW MAGAZINE. HE IS ALSO A FICTION WRITER. HIS SECOND NOVEL, ORIENT, WILL BE RELEASED BY HARPERCOLLINS IN EARLY 2015.