Trade Secrets

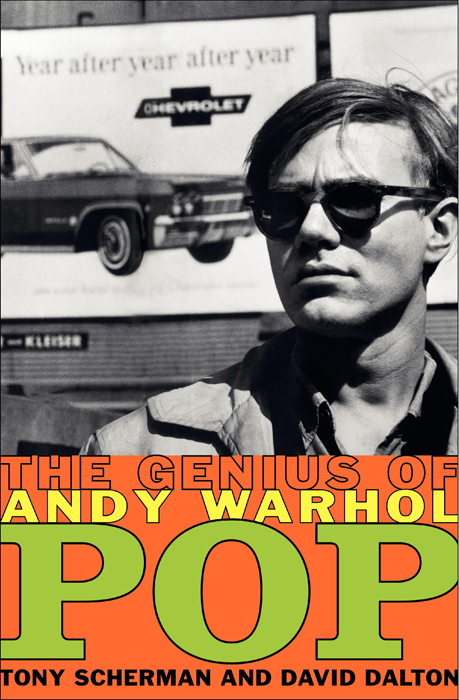

Whether you take the bowldlerized oral history of Andy Warhol as gospel or not, there’s little doubt that he was one of the more visionary artists of the 20th century. (Take this very magazine as your example). But that vision rarely began with Warhol, according to Tony Scherman and David Dalton’s exhaustively researched, seductively written new history Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol (HarperCollins).

Chief among those usurped visions is the revelation that Warhol paid uptown gallerist-turned-novelist Muriel Latow for the idea to paint Campbell’s soup cans. Ironically, he cut her a check for $100, the same amount each of the 32 paintings were originally priced at in his inaugural 1962 show at L.A.’s Ferus Gallery, before Irving Blum decided to keep them all (later selling the lot to MoMA for $15 million).

“The Muriel Latow thing was stunning to hear that it actually happened,” says Dalton of the event, which occured around the time Warhol would’ve seen (and freaked out about) Lichtenstein’s Girl With A Ball at the Castelli Gallery. “But, if you think about it, if you were writing a movie about a character like Andy, that would be just the perfect thing. I guess we should’ve reproduced the check. It’s in the Warhol Museum,” he says. “But if you had given that idea to someone else in that group of artists nobody would’ve done it in the way that he did it. Part of why he was so successful is that he was so American.”

Pop is almost a book that wasn’t. “Tony was so overwhelmed by all these years of research,” adds Dalton, an author of biographies on Sid Viscious, Jim Morrison, James Dean and, more recently, James Rosenquist, who was called in to help Scherman shape a narrative out of his vast findings. Dalton met Warhol as a Columbia student at a 1961 Christmas party and, shortly thereafter, he and his younger sister became two of Andy’s first assistants, working on the Baseball, Elvis, and Disaster paintings. “People didn’t really understand, and they still don’t understand, quite how he did [these paintings], because he actually silkscreened them twice,” recalls Dalton of Warhol’s process. “He silkscreened, painted, then silkscreened again. Otherwise the image wouldn’t pop out.”

Aside from an intense focus on Warhol’s machine-like processes, many of which Andy made up as he went along, the book burrows deep down into the politics of the early Pop scene: the inferiority complex around Castelli stablemates Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg (despite a letter Blum wrote to him in the spring of 1964 saying, “You are, for me, the most important artist of your generation.”); his sychophantic behavior around the abstract expressionists (many of whom snubbed him at his own party after his first Stable Gallery show); the radical segmentation of his social groups (advertising friends; art friends; old Serendipity-frequenting gay friends). There’s even a masterfully crafted retelling of the story behind Philip Johnson’s forced decision to cut Warhol’s Thirteen Most Wanted Men mural from the 1964 World’s Fair. After trying to obscure these supersized mug shots with silver spray paint, Warhol “made one last offer: to fill the space witha serial portrait of a ‘ferociously smiling’ Robert Moses…The portrait, of course, was rejected.” It’s a story that’s been told before, but not like this, in popular biographical format.

Equally riveting are the details about Andy’s sex life and his use of the prescription amphetamine Obetrol, which was “almost… proper” according to photographer and part time lover Stephen Shore, as well as his subsequent fascination with the A-men, whom Dalton remembers as a “feral group of gay speed freaks” who’d cause people to cross the other side of the street on sight alone. But this amphetamine bingeing coterie of Factory fixtures—including Ondine, “Rotten Rita,” Ronnie Cutrone, and Andy’s then-boyfriend Billy Linich, whose silver spray painted apartment served as the inspiration for the Factory’s shiny decor in the early 60s—were more than hangers-on, according to the authors. “At the Factory, I was a skilled technican and the name of what we did there was ‘Andy Warhol,'” Linich told them. They go on to write: “The A-men may have been spectacularly unable to succeed in conventional society and Andy spectularly able; they may have lived beyond the law and Andy within it, taking his safe little doses of prescribed speed, but he and they were, at bottom, fellow pariahs, and Andy knew it.”

Warhol gets the last laugh, which is why the book’s myth-busting focus, aside from a short epilogue, lasers in on the period between 1961 and June 3, 1968, the day he was shot by Valerie Solanas. The Interview Magazine-pushing, Studio 54-frequenting, Basquiat-collaborating artist was simply another man, or so the authors reason. With Warhol in the hospital glowing over making the cover of Life magazine (“the highest point of civilization for Andy”), only to have the cover taken by RFK, who was shot the same week, the final chapter simply concludes: “And so ended the first life of Andy Warhol.”