New York City’s Club 57 will have its moment in the spotlight

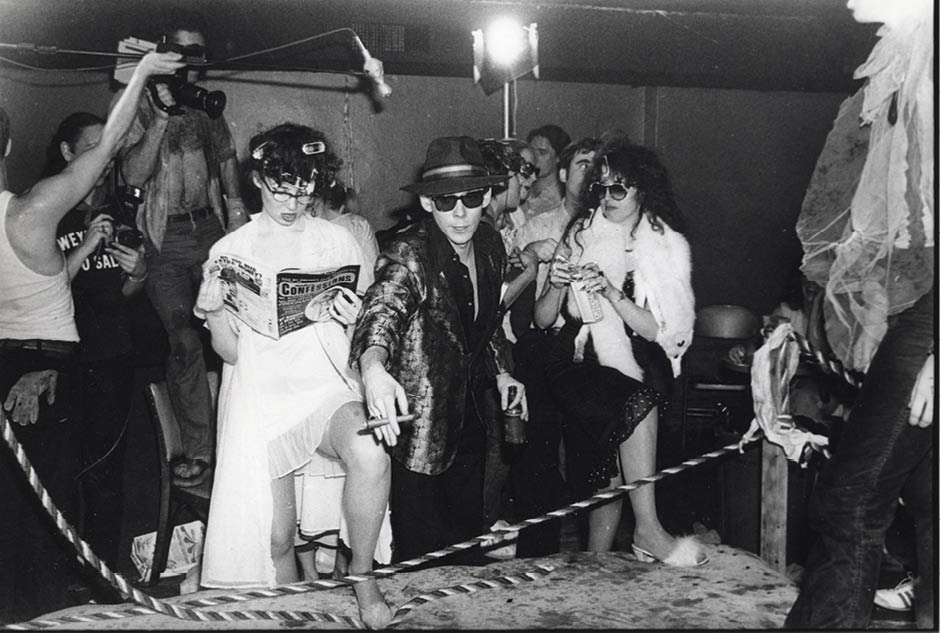

At one point or another, most art movements got their start in someone’s basement. That’s particularly true for Club 57, which, from 1978 to 1983, was located under the Holy Cross Polish National Church on St. Marks Place. Less an art movement than a wild, contagious, nonstop, free-for-all happening, Club 57 was really an open-ended forum for East Village artists of all stripes, colors, sexualities, mediums, and genders—as long as they were outsiders—to gather and have fun and create. In its five years at the heart of the downtown New York scene, it hosted all kinds of havoc, from infamous theme nights (Elvis Presley Memorial Party, Lady Wrestling, Putt-Putt Reggae Night) to spontaneous art shows (Keith Haring’s “First Annual Group Erotic and Pornographic Art Exhibition”). Several notable artists got their start there, but many more who have been forgotten by time were given free rein to exhibit, perform, and screen. Existing at a loaded cultural moment after the sexual revolutions and before the tragic impact of AIDS, when SoHo galleries were just beginning to commercialize, this debaucherous hole-in-the-street symbolized a refutation of the market, running on the twin engines of youthful enthusiasm and inventive rebellion. In a sense, Club 57 was the forebearer of the ingenious, political creativity of ACT UP and the twisted camp of the club-kid scene.

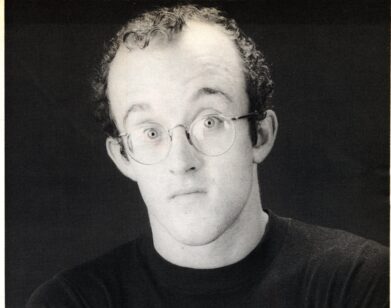

This month, the Museum of Modern Art opens an exhibition that captures the excitement and interdisciplinary influence of Club 57. The curators Ron Magliozzi and Sophie Cavoulacos tackled the Herculean task of researching and excavating the art and effluvia of a scene that prided itself on saving practically nothing. Through recovered personal videos, deep dives through archives, front covers of the New York Post, and plenty of art, sculpture, dance, music, and film, the exhibition brings to life a vital (and rarely acknowledged) moment in New York history. The performer Ann Magnuson, a guest curator of the exhibition and the club’s sometime manager, spoke with the painter Kenny Scharf about the scene they made—and how that scene made them.

KENNY SCHARF: Okay, Ann, how did it all start?

ANN MAGNUSON: It started because Stanley Strychacki [Club 57’s founder and director] had this little club in the basement of the Polish National Church. Basically, it was available to anybody who wanted to rent it out. A lot of punk bands played there in 1978, which I think is when it first opened, although I heard it was a polka club back in the day.

SCHARF: We never figured out why there was a bar in the basement of a church.

MAGNUSON: But we’re glad it was there! I was involved in the New Wave Vaudeville show at Irving Plaza, which was produced by Tom Scully and Susan Hannaford. I was credited as the director of that show, but everybody wore multiple hats, and it was where people like Klaus Nomi debuted their acts. Stanley spotted this exciting new energy happening at Irving Plaza and invited Tom to come see the space on St. Marks for himself. Tom was invigorated by the idea of showing movies there, and several months later he and Susan started their famous Monster Movie Club. Tom suggested that I become the manager, and I jumped at the chance. I started to book and run the club. I also danced when needed, which was often. I’d dance when not needed, too. [laughs]

SCHARF: There was so much creativity spilling out of that basement.

MAGNUSON: And drinking and sex.

SCHARF: Interspersed with hot, heavy, sweaty go-go dancing. That’s how I first found it. I was wandering around St. Marks Place one afternoon—Keith Haring, John Sex, Drew Straub, and I were at the Holiday Cocktail Lounge, and afterward we were walking around when we saw this little doorway. We looked inside and there was a jukebox with really good Motown music. We started dancing. And then all of a sudden—you must have been behind the bar, we didn’t even see you—you came out and started go-go dancing with us.

MAGNUSON: I was pretty much there day and night in those days. It was very chaotic for a while. Everybody pitched in. Club 57 was like the Little Rascals.

SCHARF: Our own little clubhouse.

MAGNUSON: A lot of the East Village was so bleak back in the late ’70s and early ’80s. I would describe it as Disneyland as imagined by George Grosz. There were blocks that looked exactly like London after the Blitz: bombed-out and desolate, with junkies walking around like zombies. Most of it was barren. Then there would be blocks where it felt very old country, like you were in Poland or Budapest with tree-lined streets and Eastern European folks, both young and old—mostly old. We would all meet at Ukrainian coffee shops like Odessa.

SCHARF: I was more of a Leshko’s guy.

MAGNUSON: You could always tell who the cool people were because they wore all-black and pointy-toed shoes.

SCHARF: From across the street, you could spot the artists and rock ’n’ roll bohemian types. That’s how people met each other—on the street or at the clubs. This was before the internet.

MAGNUSON: Some of us didn’t even have phones. If you look at the Jim Jarmusch film Stranger Than Paradise [1984], that pretty much gets it right. Apartments were completely empty; nobody really had any furniture. You got great furniture off the street.

SCHARF: We weren’t worried about bedbugs back then. Only cockroaches. For a while, you and I lived down the street from each other around Ninth Street and Avenue A. Club 57 was right around the corner.

MAGNUSON: Anybody could come into the club, although there were members. And there were certain people who were welcome there more than others.

SCHARF: The misfits.

MAGNUSON: It was a mixed bag. There were a lot of artists and musicians, and everybody was, for the most part, in their late teens or early twenties. Your group was still studying at SVA, and there was another group from Parsons, but people came from all over. The first members were involved in the New Wave Vaudeville show and Tom and Susan’s Monster Movie Club. Then word got around. People were always looking for spaces to show their movies or play gigs with their bands. There was a lot of alternative theater being performed as well. The East Village back then was about people being creative on their own terms, and experimenting with all the different mediums.

SCHARF: I remember that first time I came in and we were dancing—I was amazed you knew about my paintings. You asked me right on the spot if I wanted to do a show. Before that I’d only done one, with Klaus Nomi at Fiorucci.

MAGNUSON: A lot of the events we booked happened like that. When I think back, the two words that keep coming up in my mind are chaotic and collaborative.

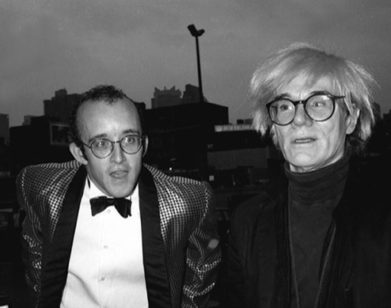

SCHARF: I think we were emulating the happenings of the ’60s and that whole vibe. We’d all learned about Warhol and his Factory. And a lot of us came to New York to find something like that, even though we knew that period was already over.

MAGNUSON: But in our own way, using the detritus of our childhood as a kind of exorcism. And as a celebration. It was a way to connect with other people in such bleak surroundings, because things were bleak back then. There’s this tendency to romanticize that period, but nobody had any money, which could get very, very depressing.

SCHARF: Nobody had any money, but it didn’t cost anything to live there.

MAGNUSON: And we made a lot of stuff out of garbage. Everybody was very resourceful in using what was available. The thrift stores were incredible. You could get a great outfit for 25 cents. I think the most I ever spent was five dollars for an evening gown.

SCHARF: That was your drug.

MAGNUSON: I had a lot of vintage clothes.

SCHARF: I think you’re being too humble about Club 57. You say it was collaborative, but you organized and curated a lot of what went on there. No one would believe how many things went on there every single night. It might have been Lady Wrestling one night and Salute to NASA another night, and Putt-Putt Reggae another night. How did that all happen day after day?

MAGNUSON: I drank a lot of Café Bustelo. That was actually my drug of choice. But let me say, at the beginning the whole organization was haphazard and collaborative. Then, in September ’79, Stanley gave me an empty calendar template and said, “Can you make a program?” Meaning I had to fill up all the nights with events. I was thrilled because I wanted to stop booking outside groups who weren’t artistically interesting. It started very simply with basic themes that got more and more complex. Tom wanted to do a night called “Iran, Iraq, and Iroll.” I made up a night based on a record I had called Twistin’ in High Society, where I cut out colored circles from sticky contact paper and made a giant Twister game on the floor, and everybody had to dress in elegant cocktail attire. And, of course, many nights would end in debauchery—even if sometimes only five people showed up.

SCHARF: We didn’t care if no one showed up. And just as often it was packed.

MAGNUSON: In October 1980, Andy Rees took over running the program, and he brought in a more theatrical vibe. He did the play Bad Seed and cast our friend Scott Covert, who had this alter-ego drag character named Becky Rockefeller. It was Scott as Becky as Rhoda, the evil little girl. This was also when Scott Wittman and Marc Shaiman, who would later go on to win a Tony Award for Hairspray, started doing their musicals at the club. There were a lot of different iterations of Club 57, depending on the year and who was involved. It was always changing form.

SCHARF: I remember nights based on old TV shows.

MAGNUSON: Oh, yeah. Remember, we didn’t really have video-cassette rentals back then. Once something showed on television, that was it. You didn’t see it again. But Jerry Beck had all these old TV shows from the ’50s and ’60s, so he and I made up a night called Television Nostomania where he screened these old shows, and I dressed up as “Mom.” I wore a wig and a 1960s shift dress, and kind of looked like my second grade teacher. Now I’m realizing that was subconsciously based on her. [laughs] And like my own mom, I served Kellogg’s Snack-Paks to everybody.

SCHARF: You really were the mom of the club. You looked after everyone—especially when there was trouble.

MAGNUSON: There was a neighbor who hated the club and wanted it shut down. There’s actually a flier that Stanley kept that says, “Stop Club 57,” with a picture of someone with their fingers in their ears. One reason I think Stanley initially brought us was because he wanted us to book events that weren’t so loud. Bands were always causing noise complaints. There was a big brouhaha that happened on Elvis Memorial Night when the juvenile delinquents from next door came in and threw beer on the faulty air conditioner, which then burst into flames. Everyone panicked and ran out—except for Jean-Michel Basquiat, who just sat at the bar and snickered.

SCHARF: One of the things that strikes me about the club that runs counter to today is that there were no labels, no fixed identities. People were so fluid.

MAGNUSON: It was all kinds of punk or new wave. No one was interested in being labeled straight or gay. It was very sexually fluid. Labels were boring and pointless. There was a distinction, though, between the people who went to Club 57 and those who went to the Mudd Club.

SCHARF: Club 57 was psychedelic. The Mudd Club was more for the down type. We were groovy. They were cool. We were obnoxious and infantile, and some people couldn’t handle it. We’d be jumping off the walls on pogo sticks.

MAGNUSON: Plus, the Mudd Club people liked to do heroin. We were goofier, and that was sort of looked down upon by people who took things too seriously.

SCHARF: There was a definite rivalry. And then, all of a sudden, the Club 57 kids started working at Mudd Club, doing the door, the bar, and organizing performances.

MAGNUSON: Steve Mass [Mudd Club owner] asked me to re-create my Playboy Bunny night at Mudd Club. And he asked Keith Haring to take over the second floor as an art gallery.

SCHARF: I was the doorman at Mudd Club, but I only lasted a week because I refused to let this guy in who was trying so hard to look like David Bowie. I wouldn’t let him in, and he was so nice about it and just stood outside very quietly. Finally I was like, “Okay, you can come in.” Two seconds later everyone inside was screaming, “David Bowie is here!” In my mind, Bowie was six feet tall, so how was I to know it was really him?

MAGNUSON: When I filmed The Hunger [1983], I was shocked by how frail he was. I thought, “My god, I could sneeze and this guy would fall over.”

SCHARF: You know, it’s amazing how much MoMA has managed to find from Club 57, because we never thought to keep the work. Everything was for one night only.

MAGNUSON: The mentality was that it was just for the moment.

SCHARF: There was no future.

MAGNUSON: Oh, that is very important to mention. We were convinced we were going to die in a nuclear holocaust.

SCHARF: Reagan felt really dangerous, although that seems mild compared to what’s going on now. But at the time it seemed really bad.

MAGNUSON: That’s why I hope this MoMA show will be an inspiration for younger kids who are freaked out about what’s going on now, especially after growing up under eight years of Obama. It’s not just about celebrating the past; it’s about inviting a new generation of kids and people who feel like they’re outsiders to start their own adventure.

SCHARF: How to survive in gloom and doom.

MAGNUSON: But also how to think in a collaborative way and work as a group. Like all boho scenes, it’s a very Rashomon situation where everybody has a different account of what happened. That’s what makes it so alive. There are so many stories that have been unearthed about the club that I didn’t know about.

SCHARF: I remember Keith [Haring] would call out to artists and say, “Come in, we’re doing a one-night show, and this is the theme.” Everyone would show up and slap up what they had made or make something on the spot. Some people came back to get their work the next day, some people didn’t. There was no money involved. There was never any talk of money. The day money actually arrived, everything basically stopped. It wasn’t that fun anymore.

MAGNUSON: The whole vibe of the East Village started to change.

SCHARF: The drugs came in. It got very dark. But we also got older, and I think people realized, “Oh, wait a second. I do need to make some money to live.”

MAGNUSON: Also, “I don’t want to live in a cockroach-infested apartment my whole life.” Nobody made any money at Club 57. That wasn’t what it was about. Some of us went on to find more sustainable jobs. Others decided to do heroin instead.

SCHARF: Heroin changed things. Some of the kids became addicts, and that took a big toll. And then there was AIDS, which devastated the art community. I ended up moving to the jungles of Brazil and had a child. You moved to Los Angeles to become a movie star.

MAGNUSON: Not exactly! [laughs] My mom moved to L.A. in ’82, and I visited and hated it. But I came back out in January of ’84 to do a performance with my folk band. There had been a blizzard in New York, and in L.A. it was 70 degrees and sunny. I thought, “Hmm. I kind of like this.” I was really seduced by the sun.

SCHARF: And rainbows. Do you think Club 57 could ever happen now?

MAGNUSON: Back then, there was such a Grand Canyon between artistry and commercial success. The idea of being an art star was not on anyone’s radar. The idea of even being successful and making money in the arts wasn’t within the realm of possibility.

SCHARF: We were just having fun.

MAGNUSON: When you’re that young, you don’t really think too far ahead.

SCHARF: Thank god. But I really think there are moments in history where things crescendo right before they crash. And New York was like that in the late ’70s and early ’80s. I remember thinking, “Wow, this is what it must have been like in Paris or Berlin before the war.” Then the crash did come. We thought it was going to be the hydrogen bomb, but it turned out to be AIDS.

MAGNUSON: We were lucky, though, to be free of all the gadgets of today. It forced us to be in the moment and not to be attached to things. Or even want things! Although now I’m seeing all of these millennial vagabonds showing up in Joshua Tree, and they’re making some really interesting work out of trash. They have no money. They’re literally riding the rails like hobos. They have that same sense of spontaneity, which is an element we had that’s really missing to some degree today when everyone’s so focused on self-consciously branding themselves. We had to walk outside to find out what was happening and run into somebody by total accident, which would spark a conversation or an idea for an event that we’d put on the calendar and make happen. It’s like the way animals deal with life. They’re 100 percent in the moment. And the East Village back then was like that. It was also a very dangerous place to be. I used to have to get an escort to walk me home at night because it was a place people got mugged and raped.

SCHARF: Luckily, I never got stabbed. I had knives and guns pulled on me but no one ever stabbed or shot me.

MAGNUSON: I had a switchblade pressed to my neck.

SCHARF: Me, too. It was a tougher time, pre-Sex and the City. We didn’t have Manolo Blahniks back then.

MAGNUSON: Well, Kenny, I actually had a lot of fantastic high heels. [laughs]

SCHARF: The point is, we let our freak flag fly.

MAGNUSON: And we created a family.

ANN MAGNUSON IS A LOS ANGELES–BASED WRITER, ACTRESS, MUSICIAN, PERFORMER, AND GUEST CURATOR OF CLUB 57: FILM, PERFORMANCE, AND ART IN THE EAST VILLAGE, 1978–1983, WHICH OPENS OCTOBER 31, 2017 AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK. KENNY SCHARF IS A LOS ANGELES–BASED VISUAL ARTIST.