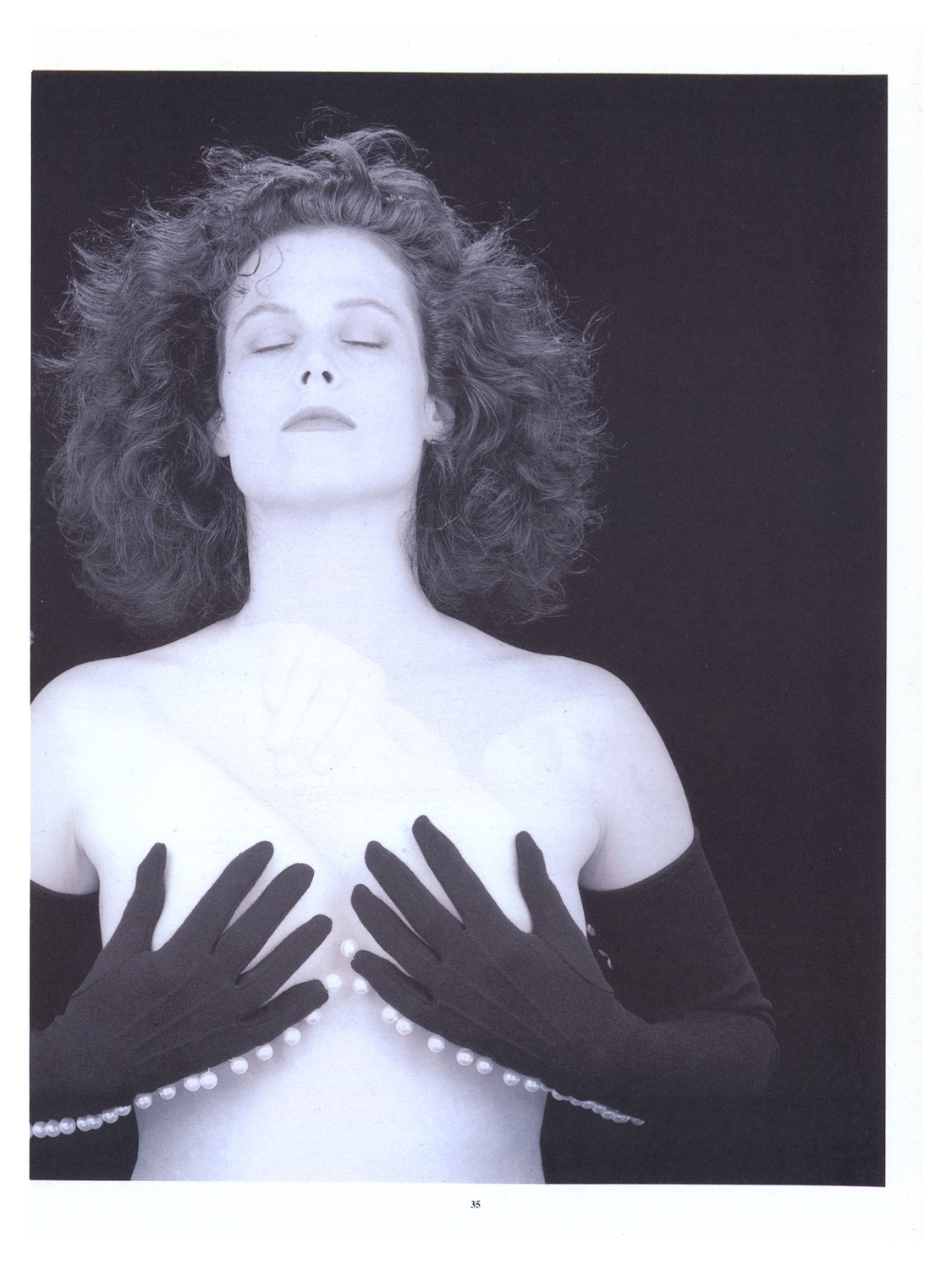

New Again: Sigourney Weaver

Sigourney Weaver is everywhere. This week, Weaver stars in Rodrigo Cortes‘ paranormal thriller Red Lights, and has a new show, Political Animals, starting on the USA Network. She’s also about to film a little sequel (to the film Avatar, you may have heard of it), and is in Amy Heckerling’s long-awaited Vamps.

One of the upcoming Weaver project we are most excited about, however, is Christopher Durang’s play Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike!, which makes its New York debut this October at Lincoln Center. The play involves an amalgamation of various themes and characters from Anton Chekhov’s plays and places them in the present day; and we do so enjoy when Durang puts his own spin on classic plays (see: The Actor’s Nightmare, 1981).

Durang and Weaver are old friends from an ivy-covered school somewhere in New Haven—the two even co-hosted an episode of SNL together. Durang interviewed Weaver for us in 1988, which we have reprinted below in celebration of their newest collaboration. Throughout the course of their conversation, Durang and Weaver cover everything about drama school, gorillas, AIDs, and psychics. It seems that Sigourney Weaver once advised Durang to seek the advice of Adrienne Clairvoyant in London—your character in Red Lights would not be pleased, Sigourney. – Emma Brown

Dream Weaver

by Christopher Durang

I’ve been friends with Sigourney Weaver since the fall of 1971, when we met as classmates at the Yale School of Drama—she in the acting department, I in playwrighting. She was the immediate star of her class—beautiful, sculpted face, slender body—and she seemed to be about seven feet tall. She looked like a mythological goddess, Juno or Diana or (why stick to female comparisons?) Prometheus or Atlas. She seemed playful too; the first time I saw her she was wearing green pajama pants with little pom-poms hanging off the sides of the legs. She later told me this was part of her “elf” costume.

We got to know each other through Playwright’s Workshop, a weekly class in which the actors read scenes from the student playwrights’ work. That December a student director, Steve Zuckerman, cast her as a woozy mental patient in my first play at Yale, Darryl & Carol & Kenny & Jenny. The original title was Better Dead Than Sorry, but I was urged to change it so audiences wouldn’t be frightened away.

The play was a cracked musical comedy from my early life-is-not-quite-worth-living period and concerned a crazy show business foursome: responsible Darryl (whom I played), his oversexed wife, Carol, his sicko brother Kenny, and his too-sensitive-to-function sister Jenny. I was still learning how actors should play my offbeat material, and Sigourney was a revelation as Jenny; she played every oddball scene as if it were the most normal situation in the world, and the comedy seemed all the crazier, and truer, because of this approach.

As Jenny, Sigourney had to sing the “title” song, “Better Dead Than Sorry,” while receiving shock treatments in a straitjacket. (Well, my early plays were very sick.) Sigourney made her own little hat for this number—a cap with empty thread spools on either side, with tiny wires sticking out of them. When the buzz sounds of the shock treatments interrupted the song, she would freeze for a moment, widen her eyes, and move her head slightly to one side. Then she’d go on with the song. It was a very delicate, and funny, way to do the scene.

The show was successful for all of us, but I sensed that the audience had a special rapport with Sigourney. Actors need skill and intelligence—which Sigourney has in abundance—but stars need charisma, which hard work can’t give you. Standing onstage with little wires coming out of her head, Sigourney had charisma.

During that show we danced backstage together nightly as a warm-up to performing, and became very good friends. Later that year we were cast together in a children’s show as Baroness Von Something-or-Other and her troll, who liked to get beaten.

Sigourney’s first year out of Yale was not too easy. Agents complained about her height and kept trying to type her as a patrician girlfriend who poured cocktails and nodded politely while the leading man talked. Her first encouragement came when John Gielgud cast her as an understudy in a tour of Captain Brassbound’s Conversation by George Bernard Shaw.

When she came back, I was lucky enough to have her in Titanic, my second workshop in New York. She played the impossibly difficult part of the multi-personality Lidia. Lidia is the captain’s daughter who boasts of having kept a hedgehog in her vagina. (I wasn’t well when I was younger.) Lidia, however, turns out to be the lesbian lover Harriet in disguise, who turns out to be the vengeful daughter, Annabella, who kills both her parents and keeps wanting the boat to sink, which it won’t.

Sigourney was fabulous in this role—innocently crackpot as the captain’s daughter, perversely world-weary as the lesbian, and then unexpectedly stirring as the angry, truth-telling daughter who dresses in a sleek black evening gown and waves a revolver about the stage. Sigourney and I continue to be friends, and our professional paths keep crossing. She performed in my Off-Broadway play Beyond Therapy; we performed our coauthored cabaret act Das Lusitania Songspiel a few times. And in the fall of 1986, when she was guest host for Saturday Night Live, she requested that I be her cohost so we could do a bit of Das Lusitania [Songspiel, 1980] and so I could be around for, well, I guess moral support. She is the only guest host to my knowledge to have requested her own personal playwright, and I felt very gratified. (She and I also got to be on the first of Dana Carvey’s Church Lady sketches—Church Lady slapped my hand for all the naughty plays I’d written.)

There are times I don’t see Sigourney for a while—when she’s off in Africa, for instance, doing a film—and I feel sad about her absence. Then, suddenly, she’ll be back in town, and I’ll have the familiar presence of my friend again. With Sigourney, familiarity makes the heart grow fonder.

CHRISTOPHER DURANG: Would you like some tea? Let’s see what I have in the cupboard. There’s Red Zinger, Cinnamon Rose, Almond Sunset, Raspberry Patch, Tetley Decaffeinated, and Lipton Decaffeinated.

SIGOURNEY WEAVER: Or chicken-flavored Stove Top Stuffing.

DURANG: I think I’m going to have the Tetley Decaf.

WEAVER: I’ll have that, too. I have no will of my own. I’d love some decaffeinated milk in mine. When do you move out of this place?

DURANG: Soon.

WEAVER: You have to sell it first?

DURANG: Yes. As a matter of fact, somebody is going to interrupt us around 3:30 to see the apartment.

WEAVER: Can I be lying on your bed in my garter belt, smoking a cigarette?

DURANG: Sure. I’ll explain that you come with the apartment.

WEAVER: A hundred dollars extra a day. [laughs]

DURANG: You’ve been filming Working Girl here for Mike Nichols.

WEAVER: I always find it particularly difficult to work in New York because there are so many things to do. By the way, I was on the corner of Park and 57th today and this man—a kind of panhandler—started mumbling something and coming toward me. I didn’t have any money at all, not even a penny, and I said, “I’m so sorry, I don’t have any money,” and kept on walking. He said, “Nooo, baby, I want some pussy.” I was so taken aback that I just burst out laughing.

DURANG: Gosh, that’s funny. You once said to me that you felt you hadn’t had the chance to do comedy on film as much as you have on the stage. Working Girl is a comedy, though, isn’t it?

WEAVER: Yes. Perhaps because I did Hurly Burly with Mike, he really persisted in encouraging me to play this part. Also, the experience of Deal of the Century made me think that comedy couldn’t work on film. You have to be so careful how you shoot it. Deal of the Century was shot in close-up when it should have been in master and in master when it should been in close-up. It was a much funnier script than what it looks like now. Ghostbusters aside—which is a special case—I really wanted to wait until it was the right part and a director as great as Mike before I did another comedy. It’s such a nice change to get to play a wretched, shallow, mergers-and-acquisitions woman. My true colors come out. [laughs]

DURANG: Is it very different working with Mike on this film as opposed to a play like Hurly Burly?

WEAVER: Well, with Hurly Burly he used to joke that women were going to be given short shrift in rehearsals. We always rehearsed at the end of the day. He used to refer to us as the “niggers.” That was the status of women in the world of Hurly Burly. There was a deep bigotry between the sexes in the play, which we had to explore in the rehearsal. He would say, “Now for the niggers.” And we used to do an hour’s worth of rehearsal. Most of his energy was going into handling all these very different actors: Chris Walken, Harvey Keitel, and Bill Hurt. In the last few years, Mike’s been so merry, but I think Hurly Burly was such a difficult play to do, and the atmosphere couldn’t be very merry, whereas on this set it certainly was.

DURANG: Have you done another film in New York?

WEAVER: Eyewitness. I never think about Wall Street—why should I—but to go down there so often while filming Working Girl, to become acquainted with this whole different world, and to find out what goes on behind the scenes is so interesting. There’s so much of the city that you don’t really bother to investigate. Ahh… New York…

DURANG: New York.

WEAVER: What did you decided to do for the AIDS benefit tonight?

DURANG: I don’t know yet. I thought I could do that speech from my play Laughing Wild that I’ve done other times, but I’m trying to come up with something lighter and sillier to do.

WEAVER: Every time I run into a friend who has AIDS I think your speech about the illogic of God “causing” AIDS.

DURANG: Are there lots of people in your surrounding life who have AIDS?

WEAVER: I saw a friend last night at the opening of a play. I was amazed to see him looking so well because he had been pretty ill.

A group of us are making a panel for the big AIDS quilt for Way Bandy. The panel has to be 6 feet by 3 feet. It really makes me angry that people are so afraid, but many people just don’t know anyone with AIDS. When you actually see someone with AIDS you feel you want to reach out to them…. They’re ill. Thank goodness, I’m not afraid anymore, but it’s still so sad.

DURANG: Yeah, well. [silence] When did you first decide that you wanted to go into theater?

WEAVER: I don’t know. I had always done theater in extracurricular ways. I’d never been a drama major. At Stanford I was in the honors program studying English and scheduled to go right into the Ph.D. program. The course started getting really boring. Finally, I went to my adviser and said, “This is a desert, this part of it, right here in the middle. I hope it’s not going to be like this for three years.” He said, “It’s going to be quite like this.” I said, “I don’t think I can stand it.” I was studying criticism of criticism. It was all this twice-removed stuff—deadly dry. So I just applied to Yale Drama School and got in.

DURANG: What did you do for you audition?

WEAVER: I did St. Joan at the Stockyards by Bertolt Brecht. I remember I wore a pair of corduroys tied with a piece of rope. [laughs] I wasn’t really prepared. I used to audition at these places on the spur of the moment. I also auditioned for Lloyd Richards, who was at NYU at the time. I hadn’t signed up at all; I literally came off the street. I told him what I was going to do and he said, “Are you going to sing a cappella?” I’m afraid I said, “I’m sorry, I don’t know how to, but I could try.” [laughs] I then announced I was going to sing a Janis Joplin song. In the end, they accepted me, but I didn’t go there. I’m not proud of it, because it makes it look like I took it unseriously, and I didn’t—I was just disorganized. I didn’t bother with English schools. My acceptance to Yale was addressed to Mr. Sigourney Weaver, so I really wasn’t sure when I got there what they thought they’d taken. My second day there I got violently ill from food poisoning and had to go to the hospital. I’d eaten liver at the Elm City Diner—I was trying to be healthy by eating liver. I remember sitting next to this window on Chapel Street that had a big bullet hole in it. I should have known then….

DURANG: Do you think that Yale was the wrong place for you to be, or was it something that was right for you to go through?

WEAVER: I met you there, and I met Albert Innaurato there, and I met Kate MacGregor-Stewart. I think it was you guys who really got me through it. In the end, that was the most valuable thing. But I do feel that it’s wrong to charge people all that money and then not cast them. I felt there was so much hypocrisy and pettiness there. But I read in John Houseman’s book, Run-Through, that drama schools winnow away people and the tough ones remain. Some of those weaker people in my class, however, were so talented. I’m sure the school didn’t say, “Let’s break down all these people and then they’ll be a success in the real world. Let’s build up all those people and make it harder for them to have the same kind of fulfillment in the marketplace.” That can’t have been their philosophy. [laughs] I think it was just an accident.

It’s so peculiar. I mean, I did learn. I enjoyed having all the different teachers. But I still wish that I had been able to have the kind of school experience that some of my English friends had at Central [School of Speech and Drama in London], where they all played Juliet and Candida. We didn’t really study Williams and O’Neill and a lot of other great playwrights because Robert Brustein [then dean of Yale Rep] didn’t particularly like them. I thought some of the shows at the Rep were just dreadful. Hated being in them, hated going to see them. I didn’t even bother to go see the ones that I wasn’t in my last year. But then I was very discouraged that year.

You kept hiring me and that was a big life—that made all the difference. If it weren’t for the Cabaret, I think we all would have gone crazy. It was the only place where we could let off steam. Yet, it I were to do it again, I would still go to a drama school, and I probably would still end up going to Yale because I liked being with the playwrights. I think that we have a big advantage over some of the other schools because we are used to dealing with new plays, and that’s where the work is. So it’s much more fun, much more exciting. What do you think? I mean, I’m still in therapy. [laughs]

DURANG: I think your career has really gone well and that you’ve gotten to a good place in your life. I’m not saying that one should choose a school where one’s going to suffer, but in some strange way I wonder if, in terms of one’s life history, one needs to go through some sort of pain. I’m not saying that it was right.

I think what happened to me was that I arrived at Yale and was not certain of my talent—where it lay and what people were going to think of it. Since everyone tended to be kinder in the playwrighting department than they were in the acting department, I actually got a lot of the encouragement that you didn’t receive. I just wonder if it’s been a strange plus for your resiliency.

WEAVER: I feel instinctively that a school, or a place that professes to be a school, should make an effort not to judge so arbitrarily. It was all politics. I still don’t know what they wanted from me. I still think they probably had this Platonic ideal of a leading lady that I have never been able to live up to. And would never want to.

DURANG: What are your earliest memories?

WEAVER: Do you want to put me into a trance?

DURANG: Yes. Think of white light. You’re going down a river, like The African Queen, a very frightening river.

WEAVER: Both our heads are shaved. Help. Help. [laughs]

DURANG: Do you have a first memory?

WEAVER: I have a dim first memory of this farm where we used to live in Sands Point, Long Island—it was wasn’t really a farm, but we kept a few chickens. Nine acres of fallen-down buildings and one house. I remember tripping and slicing my leg on some chicken wire. I remember thinking: I’m going to remember this. Actually, once during a seminar we had to go back to our first memories and I did feel as though I was raging, trying to get attention, when I was coming into the world. Who knows if that was really a memory or just an instinct….

DURANG: You grew up in New York.

WEAVER: We were on 64th Street off Madison. Our elevator man was called Morris. I remember where we lived by the names of the elevator men, who were always my best friends. I was like Eloise. The first house I ever lived in was in Maryland, on another farm. I’ve seen pictures of it but I don’t really remember it.

DURANG: Did you live there all the time, or was that just a country house?

WEAVER: I have a feeling we might have spent the summers there. My father would commute. The other house, the poultry farmhouse, was sort of my roots. We lived right near the Schusters of Simon and Schuster. I used to love going down to their place because they had a very pretty house overlooking the sea. Mrs. Schuster had a room that was filled with children’s books. She let me go in there and read anything I wanted. Then she’d give me a book to go off with. She was like a fairy godmother. If you go out to Sands Point now, it’s all asphalt.

DURANG: When you were little, what was your understanding of what your father did?

WEAVER: Well, I knew he ran a network, but I thought everyone did that. I also remember that I was very confused because I was learning my ABCs and he ran NBC. I would have preferred if he’d run ABC because that was what I was being taught.

DURANG: What years was he in power at NBC?

WEAVER: From 1951 to 1956.

DURANG: I know he started the Today show and The Tonight Show. Were there others, too?

WEAVER: Well, the main thing he did was take the power to create shows away from the sponsors. He made the programmer the creative person. He would build the show and if the sponsor was interested in it, fine—which is one way he got out of the whole McCarthy thing. The sponsors would come and say, “We don’t want so-and-so on the show representing our product.” And he’d say, “If you don’t like it for your product, go somewhere else.” In that way he was able to protect almost everyone who worked at NBC.

DURANG: What did you father do after he left NBC?

WEAVER: Some of his people were being fired and he left in protest. I think he felt that since he’d done so well—brought opera, ballet, and so many high-quality shows to the network—that other networks would be interested in hiring him. In fact, I think there was a lot of jealousy and rivalry, and [William] Paley and others wanted to keep their own power. So they weren’t going to hire this brilliant young man—he was in his early forties at the time. Twice he tried to start a fourth network, but it didn’t work. Then in 1963 he started the first major pay cable television system, which had thousands of subscribers out on the West Coast, but the theater owners put him out of business illegally. We used to get death threats at the house, and every time you went into a theater you’d be asked to sign a petition stating that if there were paid television there wouldn’t be free television. Finally, a referendum was put on the ballot, with the question phrased ambiguously, in such a way that thousands of people who wanted to allow cable service voted yes when they should have voted no. It took the Supreme Court 12 years to overturn it.

DURANG: Was your father actively involved in the suit?

WEAVER: Oh, yes. But by that time all the money had been lost.

DURANG: Did you father come from a wealthy family, or did he earn all his money himself?

WEAVER: My father’s family was rich for a while. My grandfather was the president of the Chamber of Commerce in Los Angeles. But he sold his roofing company too early, or something like that, and then they didn’t have any money. My father was one of the young men about town. He used to go out with Loretta Young and her sisters, and he went to high school with Carole Lombard, whose name was Jane Peters then. He used to date all the stars.

DURANG: How did he meet your mother?

WEAVER: It was at a party. I don’t quite know the details, but I think they got married about six months later.

DURANG: She was still an actress when he met her?

WEAVER: She had come over from England to do Angel Street on Broadway, which became the movie Gaslight. She’d been a big hit in the West End production—she played the Angela Lansbury part of the cocky, tarty maid. They wanted to bring the show to New York. But then she got another job working with Jessica Tandy in Anne of England, a show that closed after about a week or so. Because she had already done that show she couldn’t do Angel Street; she was an English actress and could do one show every six months due to Equity regulations. I don’t quite know what else she did.

DURANG: What was her acting name?

WEAVER: Elizabeth Inglis, which is my grandmother’s name. Then Hollywood changed her name to Elizabeth Earl. She’s in a few movies, but she’ll never tell me the names of all of them. She’s in The Thirty-Nine Steps and The Letter.

DURANG: In The Thirty-Nine Steps she’s in the party sequence with that guy with the missing finger.

WEAVER: She’s his daughter, Hilary. Apparently my mother had just gotten a perm, which in those days meant you had to stay in for two weeks, because it took that long to fall out and look sort of natural. She got the call as soon as she arrived home from the beauty parlor—so when you see the film she’s got a Shirley Temple hairdo. It’s not very flattering.

DURANG: But your mother stopped acting.

WEAVER: Yes, when my brother, Trajan, was born. He’s four years older than I. My mother was always a real athlete. She qualified for Wimbledon when she was 16, but her father wouldn’t let her participate. He said, “My kids aren’t going to play these rich people’s games, because they are going to have to go out and make a living.”

DURANG: Was her family wealthy?

WEAVER: Well, he father was a lawyer. I don’t think they were wealthy, but they were the gentility.

DURANG: How did your brother get the name Trajan?

WEAVER: My father loved Roman history. It’s his favorite period, so he named his son Trajan after his favorite emperor. Trajan was a good emperor—he had all his marbles and built the aqueduct and was a very good legislator. Then later Dad wanted to name me Flavia. My mother objected, so I was named after her best friend in England, Susan Pretzlik, who is a very interesting woman. She was quite an explorer. And if I had met Susan before I switched over to Sigourney when I was 13, I probably would have kept it.

DURANG: It’s funny that your name is Susan, because actually I think it fits you, but so does Sigourney.

WEAVER: I just didn’t like it because I was so tall and I hated being called Sue. But I think I’m very definitely a Suzie. My parents were so reasonable about it. They called me “S” for a while in case I changed it to something else. [laughs] And then actually they wanted me to keep the Roman part of my name, which was Alexandra—Susan Alexandra Weaver—so my father and I tried to think of a way of calling me Alexandra, but I thought it was too long. He still writes me, “Dear Dra . . . Love, Drad.” But I like the name Susan. I wonder how perverse it would be if I had a daughter and named her Susan.

DURANG: I have strange family names, too. My father was called “Boo.” My own middle name is very silly. It’s Ferdinand.

WEAVER: I think Ferdinand is a wonderful name.

DURANG: In the seventh grade, I had to apply to prep school. We had to fill out our full name and no one had ever taught me how to spell Ferdinand. All I knew was the cartoon strip Ferd’nand, with the apostrophe where the ‘i’ should be. So that’s how I wrote my name, and I was afraid I would be kept out due to that. What schools did you attend?

WEAVER: I went to Chapin, but I went to Brearley first, which was another high-powered New York school. My mother changed me because she liked the uniforms at Chapin better. When I was about 12, my parents were going to go out to California to start this cable television thing. I wanted to go away to school. I had this romantic idea of what boarding school would be like. Then I went away to Ethel Walker’s, where I just cried for the first year. That’s in Simsbury, Connecticut. I’m going to speak at the graduation. I don’t know what’s important to girls that age anymore. When I arrived at Ethel Walker’s they thought, this is the great high school basketball star we’ve been looking for. They quickly switched me out of that, because it wasn’t my thing. But I took a lot of dance. They had a good dance department there, and I think that helped me a lot. My one regret, actually, when I think about it, besides not learning science, is that I would have liked to become a choreographer. I think that’s a really interesting field. Not for musicals, but for modern dance.

DURANG: When did your interest in performing begin? Was it at Ethel Walker’s or earlier?

WEAVER: At Walker’s. I remember my second year we updated the poem “The Highwayman,” and I was sort of the motorcycle guy. I flipped my hair back and wore a big leather jacket and some girls chased me out. [laughs] I guess I did a good job as an Elvis Presley type. We were so isolated… but I always had a lot to do with those shows. We did a whole Arabian sheik show; I was the Valentino character.

When I was 16 I did summer stock at the Red Barn Playhouse or something like that, in Southbury, Connecticut. It was a pretty strange life. We worked terribly hard. The theater was too poor to buy new scenery and stuff, so we spent most of our time out in this cow pasture shooing the cows off the flats and scrubbing years of paint off of them. I got cast in a couple of things. I played all the extra women in A Streetcar Named Desire. I started out as the woman who sits on the stairs and says, “What was that package he threw at her? Meat? Ha, ha, ha.” I went up to this very fey English director we had and said, “Now, why is this funny?” He said, “Dear, if you’re too young to understand, I’m not the person to explain it to you.” Obviously it was dirty. Then I used to go and put on all this makeup to play the little old flower vendor and go “Flores! Flores para los muertos!” Then, at the end of the summer, I was cast as Alice in You Can’t Take It With You, which was probably the one good role I was going to get. Then the producer put his boyfriend in the role opposite me and fired me because his boyfriend was about half my height. I called my parents and described this situation to my mother and she said, “Well, welcome to the business.” [laughs] She said, “Your heart will be broken a hundred times….”

DURANG: Let’s talk about the gorilla film coming up. You play Dian Fossey in Gorillas in the Mist. How did that particular audition go?

WEAVER: I didn’t have to audition. They just offered it to me. Of course, luckily, Jessica Lange was pregnant. [laughs] I had read Fossey’s book a long time ago and had been very interested in her, but I didn’t think it would make a good movie. I thought she was very difficult to understand and that a movie would sort of flatten that out about her and make her too understandable. But I don’t think this film did. There is a lot of controversy over what happened. Was she racist or not? Was she raped during the civil war in the Congo?

I did a lot of research. I found she had real highs and real lows, and I certainly know what I consider to be the truth. For instance, I don’t believe she was raped. But even if you disagree with what we think are the facts, the character still has a kind of energy that could easily get someone into trouble—yet also keep one out of trouble. There’s almost nothing you can say about Dian that doesn’t have a good and a bad side to it.

DURANG: In what way would she have been considered racist?

WEAVER: Anyone who threatened gorillas in any way, she would capture. Sometimes she would beat poachers with nettles. She kidnapped one of their children when they kidnapped a gorilla baby. She didn’t want cattle tramping through the forest, so she shot thirty head of cattle one afternoon. She went to violent extremes to make her point. She was completely pro-animals. Not that she didn’t like human beings, but most people think that animals are third-class citizens. Very few people really see animals as “the others” with whom we inhabit this planet. They have equal rights with us.

DURANG: So her racism wasn’t necessarily antiblack; it was antihuman.

WEAVER: It was anti her enemies. The gorillas’ enemies were her enemies. She was very clear about that and, therefore, I think, was a very irrational, unpopular person.

DURANG: When you got the part I remember you seemed very excited about going to Africa and meeting the gorillas. I don’t want to meet a gorilla, and I don’t want to go to Africa either. So it’s good that they offered it to you and not me. [laughs]

WEAVER: They wanted to offer it to you, but I convinced them that I would be more appropriate. [laughs]

DURANG: But I was struck by the spark of adventure in you. That’s what I thought I saw in your excitement.

WEAVER: That’s why I always like doing your plays.

DURANG: It seems you had a genuine response to the gorillas.

WEAVER: Yes, it’s very true. I think it’s changed the way I feel about animals. You stop thinking of them as gorillas and you start thinking about them as who they are. They really do look different from each other, and they all have their own personalities. It’s like you’ve suddenly moved in with a group of people.

David Watts, who ran the Karisoke Research Center, was the main reason I was never really afraid of the gorillas. He would tell me that certain gorillas didn’t like people. The main gorilla to be afraid of was Pablo, who used to drag women down the mountain. But if you stayed near the big silverback, Ziz, Pablo didn’t bother you.

DURANG: Because Ziz was protective?

WEAVER: Ziz didn’t like Pablo around because they’re close in age and very competitive. Of course, Ziz didn’t like me around either and made quite a few displays. He didn’t care for all the attention I was getting. It was against their system to have a white female creature get all this attention—and I’m sure he knew I was female.

When I went up to Karisoke I said a silent prayer that I hoped I could get over any apprehensions. It seemed to me that the absolute bottom line for whoever played Dian was to leap over any conventional ideas one had about wild animals and just be there with them, because that’s what Dian’s life was about. That was the one thing I felt I had to do. David Watts took me on my first trip to see the gorillas. He said, “Let’s go—they’re about five minutes away.” Which never happens—they’re always about two or three hours away from where you are. They’re very hard to find. Once we walked eight hours to be with the gorillas. We finally found them five minutes away from Dian’s grave. We went up and I heard this “pok, pok, pok, pok, pok,” which is the sound of the male beating his chest. I looked up and saw this huge silverback just standing there looking at us. I don’t think I ever looked back after that. It was like walking into a forest and seeing a unicorn.

I sat there and saw all these gorillas from Dian’s groups—Effie and Tuck and Puck and all these names that I knew so well. Of course, David had to point them out to me. I couldn’t believe it. One young gorilla, Jozi, came down to David and picked up his camera and looked in the lens. Then she swaddled towards me and sat down. My heart was beating so fast, I was so excited—I was joyous. She was reaching over to look at my cameras and she leaned against me and just looked at me. I remember her arm was so hot, it burnt right through my clothes. I’d never been shoulder to shoulder like that with an animal before. Then she got a little bored with looking me over and just kind of ambled off.

Then there was my friend Maggie, who was the gorilla I got to know best. She was probably one of the last infants that Dian named. Now all the infants have African names. She’s about eight now. I think she would have been five when Dian died. When I went back the second time last October, we caught up to the group and they sort of looked at me and went on. I was disappointed, although it’s wrong to expect anything from the gorillas in terms of human response, because they don’t really care that much about you. But it was hard not to feel disappointed, because I was so happy to see them. Then Maggie came over the rise and looked down at the photographers and myself. She walked down to us, looked and me and then looked over at the photographers again, and she took my arm and just squeezed it. Then she went off. I had to turn away from the camera because the tears started running down my face. It was so clearly “Hi.” That’s why I don’t want to let too much time go by before I go back. I always want to go back.

DURANG: How much time could elapse without them forgetting you?

WEAVER: I think there are a few who might remember—Shinda, for example. Shinda is a young male of about 10. He really flirted with me. He used to sit around me and look at everyone, like, “She’s with me.” This, of course, is just my interpretation, but I always felt that his behavior with me was very different from that of females. Since he’s a young blackback—in about three years he’ll have a silverback—he was sort of showing off for my benefit.

DURANG: “Silverback” means gone gray, as humans do?

WEAVER: When the male is about 14, his whole back is a beautiful shade of silver gray. There’s a tremendous difference between a blackback and a silverback. The silverback becomes really big and his back is quite wide. It happens to every male.

DURANG: How old do the females usually live to be?

WEAVER: They can live to be about 45 or so. There were some females who were in their late thirties. They were still conceiving.

DURANG: Really? [laughs]

WEAVER: What’s so funny?

DURANG: Late thirties and still conceiving—sounds like lots of single women in New York would be envious of them.

WEAVER: Well, in terms of their life span, it’s as if I were conceiving at 65. The great thing about the silverbacks is that they service all the females, from the oldest to the youngest. I remember once trying to get close to Ziz, which was always a little nerve-racking, and he got up and looked as if he was going to come toward me—I was just about four feet from him—but instead he went off where a female was presenting herself. He got up on top of her and they copulated. David Watts said, “Well, he got a better offer.” [laughs]

DURANG: When you were working were there any babies around?

WEAVER: There were quite a few babies, and the lovely thing about going back in October without the tripod and the movie camera, which would frighten them, was that the babies were that much older and the mothers were used to me, and they just were all over me. I think when you see the film you’ll see that anyone would be very comfortable with them. Their world is this beautiful, lush, green paradise. They really make you happy.

DURANG: Speaking of paradise, let’s talk about est [Erhard Seminars Training]. You mentioned it earlier.

WEAVER: I just remember what happened when I brought my parents. I invited them to a guest seminar. My mother wouldn’t take her coat off, wouldn’t put on a name card, and came out and said that everyone smelled. I think they were sure I was a Jesus freak.

I was doing a seminar called the Hunger Project, which was simply about making a difference in the world. Within the context of that seminar a movie part was so unimportant. I went up for Alien and didn’t want to be bothered, because I thought I had not suffered through the Yale School of Drama to do a science-fiction movie. I read the script and didn’t really care that much for it. I went back the next day and told them so. I was flown out to Hollywood anyway to meet the head of Fox. I lost my bags, so I had to go to the interview in jeans and a T-shirt. I was very unfazed by it all because I was so busy thinking about ending world hunger. If I hadn’t been in an unambitious place philosophically, I think I would have tried harder. In fact, it wasn’t until the day before the screen test that I sat down and thought, well, Sigourney, you’d really better make up your mind if you want to do this or not. They’ve already flown you out here. If you don’t, you’d better think about ending it. I finally decided I really liked the character of Ripley as well as the designs and Ridley Scott [the director]. Besides, I didn’t want anyone else to do it. [laughs manically]

DURANG: The Hunger Project wasn’t the first thing you did with est. Did you take the normal training?

WEAVER: Yes. I took it because our friend Kate was so adamant. She said, “I want you to take the training.” When I asked why, she said, “Because I love you.” You couldn’t see Kate without her bringing it up. So I signed up. She said, “Why did you sign up?” and I said, “Well, you said you loved me and you wanted me to take the training, and I said I’d sign up.” [laughs] I enjoyed it in many ways. It wasn’t as humiliating an experience as what I’d read suggested. I loved all the twists and turns of it. Being with 300 people who were all talking very personally was a gratifying experience for me as an actor. I was amazed by all the human stories intermingling. I’ve always been very shy and sheltered; I think it was a good way of starting to communicate with people. I was taught as a child never to talk about myself, never to talk about my emotions. Of course, now I talk about myself constantly. Now I have to take reverse est. [laughs]

DURANG: I know you took the Mastery, which is a part of the est—like Actor’s Institute. I took that also.

WEAVER: Yes, and I took this other thing called Samurai. I used to sit in Samurai two mornings a week and thing, all these women have boyfriends—I know it. And I didn’t have one. I remember thinking maybe one of their boyfriends would end up with me. [laughs] And one of them did! Coincidentally, Jim [Simpson, Weaver’s husband]’s girlfriend at the time was in that seminar.

DURANG: Was this during the filming of Alien?

WEAVER: No, this was way after that. I was up for a film that was canceled about two weeks before it started. I’d prepared for it for a year. It was called Lone Star, with Powers Boothe. I was so heartbroken and shocked that studios could make a decision like that without realizing how much time and effort and dreaming had gone into it. I took the Samurai course to fill up my time. For the first time I felt like I was at the mercy of these studio people I didn’t even know. I didn’t like that feeling at all. I did a lot of thinking about what I could do so that it wouldn’t happen to me again. My main goal was to be a person that people wanted to have the experience of working with. It became less about where one’s career was and much more about the quality of the work. I felt if I was working with the proper people, that kind of thing wouldn’t happen again. Of course, that’s idealistic, but I think it’s been fairly true. It was an important time. That’s why I was there—trying to make sense of my life and career…. But I found that most of the visualization techniques that they wanted us to use didn’t work for me at all. As soon as I wrote something down I lost interest in it. So I never did any of the homework. I just didn’t want to pay too much attention to it. I had the opposite problem. I wanted to forget about it. There were people who would come in and say, “I’ve got a great idea. I’m going to bake cookies. I’m going to put the cookies in bags and I’m going to put my résumé in the bags and send them to agents, so that every time they eat a cookie they’ll look at my résumé.” It’s just that… [sighs… laughs] More power to them, but I just couldn’t bear the desperation. The Samurai became a course on how to get control of your career and the hustling aspect of it. There was very little about the art in the seminar.

DURANG: How about the Mastery itself?

WEAVER: I really don’t remember the Mastery very well. I can’t even remember what I did. You do a monologue for them. Then people write down their critiques. I think I kept those critiques for a long time because it was so heartening to get such a strong and positive response from the audience. I thought that was the greatest thing about the Mastery. It was very supportive.

DURANG: That’s true. I actually did the AIDS speech from my play Laughing Wild. I hadn’t written the play, but I had written the speech. It was an interesting experience for me because most people didn’t know who I was. We had a whole bunch of people from real estate taking the course for some strange reason, and they didn’t follow theater. And the people who followed theater just didn’t look at my name tag closely, because it said Chris real big, but the Durang was small. I actually valued that because I got all this response to what I had done as a Joe Blow off the street. When I act, the audiences often bring to the theater what they think of me as a writer. But, yes, I was very excited and heartened by the comments, which, like yours, were very favorable.

WEAVER: It also really made me realize that although things weren’t going well, I was incredibly lucky to be where I was. I didn’t have to take cookies to agents. I had lost a film, but I was the lead in the film. What was my problem? I think I’ve never forgotten that.

DURANG: I’m still learning that. Some days I’m furious that I don’t have Broadway plays running and more in the bank account, but other times I realize that, compared to writers who can’t get their plays produced, I’m incredibly lucky…. This is a non sequitur, but do you know the first time I saw a psychic was because you had recommended her to me?

WEAVER: Which one was that?

DURANG: Adrienne Clairvoyant in London.

WEAVER: Oh yes! She was the best. If we could only find her again.

DURANG: Her phone has been disconnected.

WEAVER: We need to go to a psychic to find our psychic. [laughs]

DURANG: What are your thoughts about psychics?

WEAVER: I certainly believed in her. I’m trying to remember if I’ve been to anyone else.

DURANG: I went to one in the Ansonia Hotel that Dianne Wiest had been to, and I thought he was very good.

WEAVER: Adrienne Clairvoyant was an amazing experience for me. First of all, I liked her so much because she was really like Mrs. Piggle Wiggle or something. She said such reassuring things. At that time I had just finished Alien. It had been an awful experience. But I didn’t tell her I was in show business. I think I even told her my name was Susan. Yet she ended up grasping everything. She said I was in the public eye and got to work with many interesting people. She also named several specific events in my life, past and future. She said that I probably wouldn’t get married until I was 35. I sort of screamed, “Thirty-five!” It was eight years away. I thought, God, it’s a lifetime. In fact, I got married a week before I turned 35. I also remember her looking at my hand and going, “What’s this? Ugghh! Ugghh!” and she grabbed her stomach and said, “You were in a bad place; it’s not good. It’s in the past.” We figured it had to be the Yale Drama School. [laughs]

DURANG: I know that you’re happily married now, but before that, how did you find it being perceived as a great beauty while at the same time looking for relationships? I remember when the critics reviewed you in my play Beyond Therapy, they often said things like, “Well, this woman is too attractive to have problems with relationships.” I thought that was such a stupid comment.

WEAVER: Gee, it makes me feel like I should have had more dates. I just don’t think of myself that way. I think we’re lucky that our business is so social that we don’t have to go out and date all the time. We can get a lot of laughs at work. But I had reached the point where I thought, well, I’m successful. Is this it? There must be something more interesting than this.

DURANG: Another thing about Adrienne—when I saw her I told her that you sent me, but otherwise she didn’t know much about me. She kept seeing you floating in my aura and after a while she said she was confused and couldn’t figure out whether it was just because you sent me or because there would be some professional thing. My question is, when will we work together again? [laughs]

WEAVER: I’d love to do your play Laughing Wild somewhere.

DURANG: [The doorbell rings.] Oh, this will be the real estate people.

WEAVER: Should I go lie down on the bed? [laughs]

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE JULY 1988 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again, click here.