Richard Nash, Head On

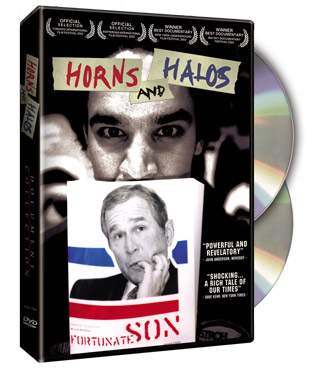

Last week, Richard Nash stepped down as editorial director of Soft Skull Books and executive editor of its parent company, Counterpoint. That might sound par for the course in a publishing world whose general tenor was nervous even before the economy tanked. But since 1992, Soft Skull has been different: It’s the beloved Brooklyn-based indie publisher that gleefully embraced its iconoclastic, second-borough status—even when it moved to Chelsea last year. After all, it’s the group published James Hatfield’s controversial Fortunate Son—the book that discussed W.’s early cocaine use and general delinquency—after established press St. Martin’s dropped the book because Hatfield was an ex-con. The whole affair was chronicled in the 2002 documentary Horns and Halos, and showed the desperate gambles independent publishers must take just to survive. Nash has piloted Soft Skull since 2001 through all sorts of economic turbulence, eventually finding a haven for the imprint in Counterpoint. However, while the group will continue to churn out controversial literature, Nash has decided to explore new areas of the publishing world.

CARA PARKS: How did you come to work with Soft Skull?

RICHARD NASH: I fell into it. The guy [punk-publisher Sander Hicks] who founded Soft Skull was also a playwright and I was directing his plays. Around 2001, things got tremendously financially complicated. I was working on a play at the time, and working part-time for another publishing company, but without any vocational interest in working in publishing at all. It was a way to get health insurance. For a variety of reasons that required a whole documentary [Horns and Halos] to go into even one of them, the founder took a sort of sudden leave of absence. I was the only adult around to try to save the business. I agreed to help out for a while as a short-term, gratis thing because Soft Skull seemed like a really worthwhile venture and it would be a pity if it fell apart. I fell in love with publishing over the course of a year, and ended up getting deeper and deeper into things, even though it was in terrible, terrible financial state.

CP: Was that the reasoning behind the merger with Counterpoint books?

RN: No, this was all back in 2001. There were all kinds of ups and downs after that. Mostly, Soft Skull grew quite dramatically. At times, it seemed like we would be completely out of the woods. At times, [there were challenges] just by the very nature of independent publishing. We never got capital from investors, or could ever obtain any kind of small business loan, because no one loans you money unless you have collateral to put up against it. Then in late 2006, our distributor went bankrupt, owing us four months of sales … and that was basically the sledgehammer that broke the camel’s back. It would have taken a lot less, but that was what we got.

CP: On your blog you mentioned that people in publishing are going to have to start re-justifying their percentage of a book.

RN: I mean we’re basically going to have to re-justify our existence [LAUGHS]

CP: Who do you think is going to be on the losing side of that re-adjustment?

RN: I honestly don’t know yet. It is very complicated for an unknown writer to reach an audience of readers given the vast numbers of unknown writers out there. How do people find out about it? So I believe in the role of intermediaries. People always look to trusted friends who might be more expert or knowledgeable in a given area for advice about things, whether its what to eat, what to wear, who to love. Well, who to marry at least. The question is, who are going to be those people. The model is going to shift from kind of a gatekeeper model to an advisor/service model. Or lets say from a bouncer model to a concierge model.

CP: What are some of the changes you envision the Internet and developing technologies will have?

RN: Almost every change in technology has resulted in a broader dissemination of knowledge and the previous gatekeepers of that knowledge were freaked out by the knowledge that they were losing their capacity to deny people access to it and freaked out about and losing their status.

CP: There is a lot of talk about the end of the publishing world.

RN: It will be a hard transition to go from one model to another of how we connect writers and readers. Things are changing so quickly, that figuring out how to make a living doing that, figuring out how to not fuck up writers’ careers while doing that, is really hard.

CP: Do you have any plans, or know what part of the publishing world you’d like to focus on right now?

RN: In the long run, I want to help develop the models that will allow the connecting of writers and readers as richly as possible. That’s probably something that I’ll both want to be doing directly myself and helping others do.

CP: The publishing industry is so skittish right now, do you think there will be a lot of experimenting going on?

I was chatting yesterday with a wonderful guy yesterday, [rare books dealer] Bob Gray. He was pointing out how in anthropology there’s a theory of refuge and prospect. Refuge is the cave and prospect is the savanna. You’re safe in your cave, but you have to go out on the savanna to eat. You spend too much time out on the savanna you get eaten, you spend too much time inside the refuge, you starve. Who knows what’s going to happen with Simon and Schuster? What I do know is that there are going to be intermediaries, and they’re going to need to strike a balance between refuge and prospect.

CP: Can you talk about what motivated you decision to leave Counterpoint?

RN: Prospect, in effect. I felt like I could more usefully participate in the future of publishing outside than inside. That’s the baldest answer.

CP: That was quite a bold move.

RN: I left this job by choice and a lot of people are leaving their jobs preferring to stay in the cave a little longer, and I voluntarily left the cave. But it doesn’t mean that I don’t recognize that life out on the preserve can be really scary at times, when you see a lion behind that tree over there. Damn, am I working that metaphor. [LAUGHS]

CP: [LAUGHS] You’re a brave man, out on the savannah for all of us.

RN: Well, there are people who got thrown out on the savannah along side me, so you know, brave, foolhardy, I don’t know.