Mariel Hemingway

THIS IS WHAT HAPPENS IN THE KENNEDY FAMILY.’ ‘THIS IS WHAT HAPPENS WITH THE HEMINGWAYS . . .’ IT KEEPS BRINGING LIFE TO THIS IDEA THAT A CURSE EXISTS THAT YOU CAN NEVER GET OUT FROM UNDER. Mariel Hemingway

Mariel Hemingway was born in 1961, almost five months after her grandfather, Ernest, took his own life in the nondescript foyer of a house in Ketchum, Idaho. As a kid, she avoided that room at all costs. Barring the living Kennedys, there is perhaps no one in America who is as haunted by the death of someone they never met as Mariel Hemingway. Now, 52 years after her grandfather’s death, she is finally facing the Hemingway legacy via the revealing new documentary Running From Crazy, directed by the Academy Award-winning Barbara Kopple and premiering next year on the Oprah Winfrey Network after a theatrical release.

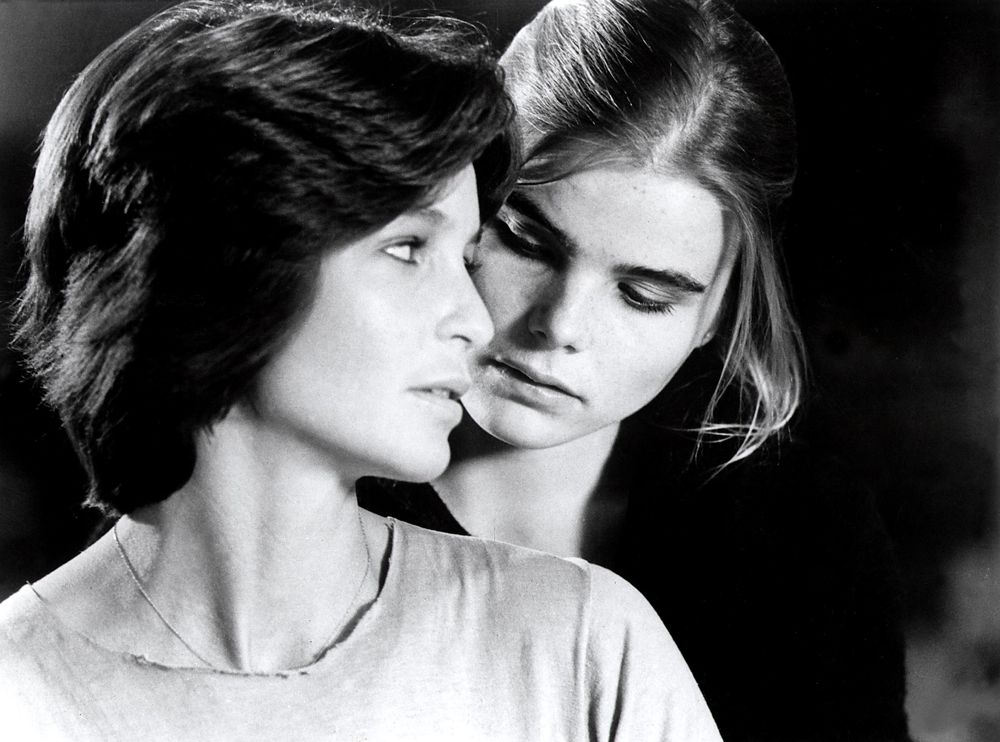

The youngest of three sisters, including model and actress Margaux Hemingway, who committed suicide at the age of 41, and Joan “Muffet” Hemingway, who suffers from bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, Mariel has long played the role of the even-keeled child. Margaux got Mariel her first acting role, in the 1976 revenge drama Lipstick, which aggravated tensions between the sisters as the public spotlight shifted to Mariel. By the time of her Academy Award-nominated turn in Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979), Hemingway was shouldering the burden of several family suicides, a childhood impacted by abuse and addiction, and a dark literary legacy she can’t actually outrun (her eldest daughter, model Dree Hemingway, attended Ernest Hemingway Elementary School as did her younger daughter, Langley, and Mariel herself).

Running From Crazy shifts between present-day Idaho, unseen footage that Margaux shot for a documentary on her grandfather, and interviews with Hemingway’s daughters. But it always hinges on the lessons it’s taken Hemingway a lifetime to learn: stop running. There is a way to be in your family and be your own person at the same time and a way to step off the path that leads to suicide—so long as you’re willing to enter all the rooms.

SLOANE CROSLEY: Hi, it’s so nice to talk to you. Thank you for doing this.

MARIEL HEMINGWAY: Of course. How are you?

CROSLEY: I’m good, aside from the fact that I just finished watching a documentary about depression in a house in the woods in upstate New York, in the dark.

HEMINGWAY: [laughs] Oh my god!

CROSLEY: No, it was incredibly touching. I welled up at least twice: once, when you go with your daughter Langley to speak at a suicide prevention walk, and also when you’re talking about your sister, Margaux, which I’ll get to later. When did you have the idea to make the film and how long did it take?

HEMINGWAY: Well, first of all, it really wasn’t my idea. My really good friend was working at OWN at the time. She was like, “We got to tell your story.” Because we’ve been through a lot of, like, “woo-woo” shit together trying of find ourselves. [laughs]

CROSLEY: Wait, what is “woo-woo” shit? Are there retreats involved?

HEMINGWAY: Yeah. [laughs] You know, soul-searching, “I’ll figure this out. I’ll be better at life.” My whole thing was always about reaching outside myself to find what was right for me without realizing that the answers were inside. But it took me so long to get there. So anyway, my friend said, “You’ve got to make a film about your family,” and I said “Are you fucking out of your mind? They’re crazy!” And she’s like, “That’s the point.”

CROSLEY: I can understand why you’re so protective, especially with so many years of the public wanting a piece of the Hemingways.

HEMINGWAY: Exactly. I said, “It could just turn out to be like a horrible reality show.” Then she said that Barbara Kopple was interested in directing it. I went, “Hmmm, that changes everything,” because she’s an artist. She’s a filmmaker. And I’d always been a big fan. I thought, Wow, I should definitely at least meet with her. And when I met with her, I just fell in love with her. She’s so passionate, she knew more about my family than I did. So we embarked on this journey together. It took two years.

CROSLEY: Two full years?

HEMINGWAY: Well, she wasn’t with me all that time, we just planned out different times that we would meet and do an in-depth interview and conversation. It was so powerful for me. It was almost like it was the ultimate therapy. I made a pact in the beginning to be honest about the story. I was going to be truthful, and you can’t just partially tell the truth.

CROSLEY: It’s like being partially pregnant.

HEMINGWAY: That either.

CROSLEY: It’s tough to lie when there’s a camera rolling for so long.

HEMINGWAY: You can, but people can sense it, they can smell it. They know when you’re not telling the truth. Then it does become reality-show bullshit.

CROSLEY: Now I have to go ahead and skip to the other moment I welled up. There’s a moment where you talk about Margaux. I can feel how hard it is for you to get the word out—that you thought she was stupid. It certainly doesn’t come off as rehearsed or fake.

HEMINGWAY: Yeah … That was very hard.

CROSLEY: Towards the beginning of the film you compare your family to the Kennedys in terms of being the other notoriously tragic American family. Sure enough, you mention seven suicides. I know the idea of listing them might seem macabre, but will you?

HEMINGWAY: There was my grandfather Ernest Hemingway’s father, my grandmother Hadley’s father, my grandfather, my great uncle, my uncle, a cousin, and my sister Margaux. And there’s probably more.

CROSLEY: Most people have one legitimately crazy relative. Not mildly bipolar, but someone who, if I presented you with a history of incidents, you would say, “Yes, that’s certifiable.” I have one in my family. But because I have one, I’ve never thought, Oh no, this could be me. You’re a very different case. Can you recall a shift from thinking, “Suicide is happening to them” to “Suicide is a gene I could inherit”?

HEMINGWAY: It was always a part of my life. That’s the reason why I called it Running From Crazy. I’ve never not been running. When my sister died, I thought the baton had been passed and now it was my turn to go crazy.

CROSLEY: Really, like it needs a host body?

HEMINGWAY: Yeah. It took me a really long time to separate myself from it. I always thought, “Oh fuck, now it’s my turn. I’m going to get sick, I don’t know what’s going to happen.” So it was all the more reason I got very, very adamant about my lifestyle, and it’s why I write books about health and wellness, like Running With Nature [Changing Lives Press]. I really felt that I had to stay level, I had to control, I had to know what I was eating, I had to know what I was doing, I had to work out. All that stuff is very powerful and it really helps, but now I don’t do it out of survival. At first, I was just trying to survive. I assumed at some point I’d be screwed otherwise.

CROSLEY: This is kind of a stretch, but Angelina Jolie recently got a double mastectomy to prevent an almost certain diagnosis of breast cancer down the road. Do you feel like being so in control was a means of trying to stop what you consider this inevitability of craziness?

HEMINGWAY: Here’s the truth of it, and it’s what I say in the beginning of the film—I think this is not a story of tragedy. It’s about discovering that everybody has a way out. Number one, we have to talk about it. Number two, you can actually address things from a purer and honest direct line to what’s been going on in your life and how you’ve been feeling and why you think the way you think. I do think there is a genetic predisposition for mental illness, for depression, for suicide, but I also think that lifestyle can change things. If you’re an addict, if you drink and you’re putting a depressant into your body, it’s going to cause serious problems.

CROSLEY: Like pouring gasoline on the fire.

HEMINGWAY: Yes. I mean, that’s what happened with my sister Margaux. Honestly, I didn’t think she would be the one who would commit suicide. Now, obviously, you can see it in the film, in her footage.

CROSLEY: The movie itself is like a matryoshka nesting doll. You’ve got a documentary within a documentary. I thought it was cool that you had so much Margaux footage that she shot for her own documentary on your grandfather beginning in 1983.

HEMINGWAY: I didn’t know we had it when we started! Barbara found 43 hours of uncut, unseen footage that my sister had made.

CROSLEY: You talk so much about feeling unseen within your family, and meanwhile here’s this footage where your sister says she feels the same—and it literally went unseen.

HEMINGWAY: No one in my family felt they were appreciated for who they were. I knew that Margaux felt out of place and that she was in pain. But I didn’t realize how powerfully affected she was by everything. And when I said I thought she was stupid … Yes, that was a horrible admission for me. I was embarrassed.

CROSLEY: I will say that sometimes the film mentions shocking things in passing. Like, that time Margaux says she cut your eyelashes off with scissors.

HEMINGWAY: [laughs] Well, you know …

CROSLEY: Is it very difficult for you just to talk about her now?

HEMINGWAY: It’s hard.

I WAS SO FEARFUL. I WAS SO FEARFUL OF THE FUTURE BECAUSE I WAS SO SCARED OF MY PAST. SO IF YOU CAN WORK TOWARDS BEING PRESENT, THEN YOU CAN SHIFT. Mariel Hemingway

CROSLEY: You’re a vocal advocate for reducing the stigma of suicide, but it’s one of these rare issues where “stigma” is not the only view of it. It’s also romanticized. People are fascinated by the darkness. Do you ever get the sense that people are glamorizing the Hemingway problem?

HEMINGWAY: There’s always been an odd sort of fascination. It’s like living in a fishbowl and growing up being very self-conscious. Seeing old footage of me in interviews—and I hadn’t seen those either—I was so reserved, so quiet. I remember thinking that maybe if I just stay super-still …

CROSLEY: Then the snake won’t bite me?

HEMINGWAY: Yes. In those interviews I was still worried about being judged. I think my life was, again, about how can I keep myself in control. How can I just get through this and be okay? And, you know, you turn the corner. You realize that you’re not imprisoned by your life or your circumstances or your genetics or anything. I really believe that we all have the ability to come out of our story. But you have to tell your story first in order to come out of it.

CROSLEY: In the film you talk about that self-enforced sanity you have and your role as martyr in your family. I wonder, do the rest of the family see you as the control in the experiment?

HEMINGWAY: Oh, definitely. I was looked at as the one that didn’t need any help, didn’t need any attention, because I was okay. But when I moved to New York at 16, I really wanted somebody to say, “Don’t move to New York, we’ll help you, we love you and we want you to stay.”

CROSLEY: You wanted parents.

HEMINGWAY: Yeah, but there was no argument whatsoever. I felt, oh, shit, now I have to go. And even though it was a relief in a way, because I no longer had to be my mother’s caretaker, I felt abandoned, even though I was the one that went …

CROSLEY: You have two very independent, beautiful young daughters. I kept wondering when I was watching the sections of the film with your daughters—do you find yourself over-parenting with them? Are you on depressive high alert?

HEMINGWAY: Not anymore. I was worried when they were younger. Langley was the quiet one who spent hours and hours by herself in her room. And I kept wondering, am I doing the right thing?

CROSLEY: Her drawings are amazing.

HEMINGWAY: If you see her stuff now, how far she’s come even since the film, it’s unreal. Yeah, so I was really on high alert. And Dree was the crazy one; she was like, “I’m crazy. Fuck everyone. I’m going to go do what I want to do, eat food I want to eat. My mother is nuts and my mother told me that rice cakes are cookies. I fucking hate her.”

CROSLEY: Did you ever tell Dree that rice cakes were cookies?

HEMINGWAY: Yeah. [laughs]

CROSLEY: Eh, it’s her fault for believing it.

HEMINGWAY: Exactly! It’s not my fault. What’s great about it is she’s come full circle. She’s 25 and she’s less, “I know everything—you’re fucking crazy.” Now we have such a powerfully close relationship. But it was challenging. Also Dree was really defensive about Margaux. That has always been hard for me because I was like, “You don’t even know her.”

CROSLEY: Dree actually says the phrase “role model” in reference to Margaux. Maybe it’s simply that if Dree decided to be a writer instead of a model, she’d feel that connection with the ghost of your grandfather.

HEMINGWAY: Dree knew the model of who Margaux was, just like the public did. She didn’t know her journey, she didn’t know her mind, and she didn’t know how I felt about her, or how I had discovered who she was and the pain that she was in. On the other hand, I completely understand. She’s a model, Margaux was huge for however many years it was in the late ’70s. So I understood her connection with Margaux on one level, but on another? I was hurt. I was like, “Why am I not your role model? Why can’t I be your role model”?

CROSLEY: In the film, you were talking about your relationship with Margaux and how she got you your first job in the movie Lipstick [1976], but then she was none too pleased that you were rewarded for your performance and she was not rewarded for hers. I hope this isn’t offensive, but I felt like I was watching a real-life Whatever Happened to Baby Jane [1962].

HEMINGWAY: [laughs] Yeah, I know. I get it.

CROSLEY: There are moments in that footage where she asks after you and then clams up at the mention of your name a little bit. Or maybe a lot.

HEMINGWAY: When she’s in Idaho and finds out I’m in New York, she says, “Oh, good. I can drive her car.” That’s a sibling thing. “Oh, good. She’s out of the way. I can use her room.” Some patterns never change.

CROSLEY: I’d like to talk about the lion in the living room—your grandfather. Ernest Hemingway was frank in his writing about that struggle with life and death and the necessity for that struggle. It’s all over in Death in the Afternoon. He’s not alone. Take Hunter S. Thompson or Sylvia Plath. I was thinking about this historical tendency with writers and how it crosses over with the rest of your family who aren’t writers … There’s a question in there but I can’t find it.

HEMINGWAY: No, I got you … That’s why it’s cool that it’s a regular person asking questions. Don’t get me wrong, you’re quite extraordinary. [laughs]

CROSLEY: More regular.

HEMINGWAY: I think that things like curses or whatever—those labels—come from belief systems, universal belief systems. So when you get a global consciousness of something, then that becomes a quote-unquote “truth” for everybody. You know, “This is what happens in the Kennedy family.” “This is what happens with the Hemingways.” And the more people believe in it, the more it kind of resuscitates the problem; it keeps bringing life to this idea that a curse exists that you can never get out from under. And so that’s really what I want the film to be about: that we all have the ability to break chains, crush curses—you know, fuck it all. Because it’s all in a belief system, you know what I mean? If you don’t buy into the belief system—which I did my whole life because how could you not? It was the way I was brought up. It was the role I played, and it was the family that I came from. But we do have the ability to shift those paradigms—by shifting our belief systems, by working on ourselves, by looking very closely at how we show up in the world. It’s why I’m into health and wellness. It’s why my partner and I are very focused on creating a life that is about being connected; it’s about being present. Because my life was probably so much in the past. I was so fearful. I was so fearful of the future because I was so scared of my past. So if you can work towards being present, then you can shift.

CROSLEY: It’s funny because every time I read a diet book—or, okay, a review of a diet book—or even as I’m listening to you now, most of life’s lessons are told to us very early. You already know how to live. No one is hiding the information from you: Don’t let other people define you; don’t judge a book by its cover; don’t put all your eggs in one basket. And then it takes you the rest of your life to be like, “Okay, I get it now.”

HEMINGWAY: That’s the thing, right?

CROSLEY: Anyway, you do end up, as Dree encourages you to do, visiting your eldest sister, Muffet. I don’t know if you’d heard this story before Muffet started telling you on film, but she talks about being five and getting painting lessons from Miró and Picasso.

HEMINGWAY: I had heard that story before. But there was a clarity to how she told it that I hadn’t paid attention to. Because of Muffett’s schizophrenia and her lifelong battle with mental illness, there’s always some fantastic story. She tells one where she’s got gabillions of dollars—whatever that means—in Russia, so we hear these stories and we laugh and we’re like, “Oh, yes, thank you so much. I’m glad you’re going to share it with us.” But this story about Picasso and sitting on the lap of her grandfather? I don’t have my dad to ask and there’s nobody that I know who was there, but I have a very strong suspicion that that’s quite possible. I mean, she was in Havana while my grandfather lived there …

CROSLEY: Did you ever go to Cuba to visit the town you were named after?

HEMINGWAY: Yes. I’ve been, like, four times. I love it there, it’s incredibly beautiful. It’s impoverished and there’s all kind of things wrong with it, but there’s all kind of things right with it, too.

CROSLEY: Do people know who you are down there?

HEMINGWAY: They do. I should just go down and be a celebrity there, use the Hemingway name.

CROSLEY: It seems to work fine in America, too.

HEMINGWAY: Well, in America, it’s questionable. Unless you lived through the ’80s, it’s like, “She looks familiar … Oh, that’s Mariel Hemingway. Is she a painter?” Especially on the West Coast.

CROSLEY: “Hemingway … Hemingway … She was in that HBO movie, right?”

HEMINGWAY: Yeah, exactly. Or, “Oh, I know her daughter. She’s an amazing model.” [laughs]

CROSLEY: Did you see the Hemingway & Gellhorn movie?

HEMINGWAY: I thought it was so embarrassing. It was so bad and I really wanted to love it. I loved it when they were making love in shrapnel, and dust and fire and smoke is everywhere. I was like, “Really?”

CROSLEY: Wait, that’s not how everybody does it?

HEMINGWAY: [laughs] “I want you … In the middle of a war zone.” I like everybody involved. The filmmaker’s great, I love those actors. I was just like, “Oh, well … Whoops.”

CROSLEY: When you were a kid, people must have known who your grandfather was. Socially and professionally, as a young female actor, were you defined as “Ernest Hemingway’s granddaughter”?

HEMINGWAY: Oh, yes. I mean, back then it was closer, so there was that. It was always a part of how people viewed me.

CROSLEY: Closer in time to his death, you mean?

HEMINGWAY: Yeah, I just think people really were much more in tune with him, and therefore they mistook me for being more directly connected to him.

CROSLEY: Your eldest daughter clearly has no problem using the name. And Margaux seems less conflicted and more grateful that it got her a foot, a gam, and a thigh in the door.

HEMINGWAY: Oh, absolutely. That always kind of bothered me because I felt like it was such a heavy thing to hold or to carry. The name is amazing but you also don’t want to bastardize it or make it cheap. I just felt that there was some sense that you had to honor the name. And that’s what I had such a hard time with my sister about. Because she wasn’t … I didn’t realize how fucked up she was or on how many drugs … You know, I just didn’t realize how difficult life was for her.

CROSLEY: Did you know she was dyslexic as well?

HEMINGWAY: I knew she was dyslexic. I knew she had trouble with alcohol. But I didn’t know it was ongoing. My perception of her was that everything looks okay, because, as we do with family, we come back together at Christmas, and then she’s playing the role, she’s got her shit together, and she’s outspoken. She puts on a show for the entire family. I didn’t see her how she was back then and how sad she was. God, the sadness in her eyes when she’s talking to my dad. And how unseen or disconnected she felt … It was profound.

CROSLEY: I won’t go into it too much because I don’t want to give away every detail in the film, but you mention that you suspected your father of having an unhealthy relationship with your two older sisters.

HEMINGWAY: I think I was not consciously aware of something at the time. I don’t think you’re aware of the wrongness or the rightness of things when you’re a child. I just know that I had perceptions of some wrong things that were going on.

CROSLEY: I think this film is very helpful when it comes to talking about the truth of depression. You visit Ernest’s grave and there are little bottles of Jack Daniels that people have left. It says a lot about who people think he was.

HEMINGWAY: Yeah, and that’s not who he was. That’s not how he wrote. People have misconstrued the perception of his art by thinking that his art came from being drunk. It never did. He never wrote drunk, he never wrote beyond early, early morning. There are things that people have glorified, that living the life of courage is about being fucked up. But he wasn’t. He was actually very disciplined. Yes, he drank too much and he lived a hard life, but he was extremely disciplined and he was a deep, deep thinker. I think it’s the misperception of addiction and living life on the edge, as if it’s cool. So many writers glorify my grandfather’s way of living as much as they glorify his work. And so they try to mirror that.

CROSLEY: I know people latch on to tragedy, make it legend right away. Maybe it’s cynical of me but I’m almost worried for your movie. You do give people a tour of the room where Hemingway killed himself. There’s a shot where the camera focuses on an overhead lamp, and I thought, “Now people are just going to wonder if he was looking at that lamp!”

HEMINGWAY: Showing the room wasn’t done as a way to understand my grandfather’s thinking at the time he killed himself. I hope people get that. It was used as a way to understand why I always felt afraid in the house, why nothing really felt normal, and I didn’t even know why. So, energetically, it’s just showing that shit happens in places, and we avoid them, we don’t even know why. It’s more about that than glorification of where he did it. There’s nothing beautiful about somebody killing themselves. It wasn’t an extraordinary room. There wasn’t an extraordinary view. It was very bad and he was at the end of his life. He couldn’t write anymore, and that is what destroyed him, because that is what he was—he was a writer. And when he couldn’t do the very thing that he was put on the earth to do—or at least that’s how he saw himself—he might as well be gone. So looking at that room? It’s meant to de-glorify the act.

CROSLEY: Okay, I would like to lighten this conversation up. Or, shall I say, foam it up? In passing, you mention putting yourself on a coffee-foam diet during your control phase. Is that what I think it is?

HEMINGWAY: Did I mention that?

CROSLEY: I wrote it down: Coffee. Foam. Diet.

HEMINGWAY: I was obsessed with food and obsessed with not getting fat, you know, the whole fucking thing.

CROSLEY: Is part of that because of your sister’s weight gain or being an actress or because everybody in your house is a model?

HEMINGWAY: Part of it was being an actress, but it was also looking at my sister; it really bothered me that she got heavy. And people would mistake me for Margaux, and then I’d think, “They think I’m fat.” I was messed up. So the coffee foam diet. [laughs] I would put, like, a tablespoon of instant, organic coffee in a blender with about a cup of hot water. Then I would add ice. It would make a foam shelf of about a foot. And I would eat the foam, which basically was eating air. I did it a couple times a day. I was jacked up on coffee and starving myself.

CROSLEY: This might be a bit silly, but do you remember the last line of Manhattan?

HEMINGWAY: “You have to have a little faith in people.”

CROSLEY: Exactly. In spite of corruption.

HEMINGWAY: You have to have faith it will all turn out okay. That’s interesting. I think life mirrors the art that we do, because I want to act again.

CROSLEY: Do you?

HEMINGWAY: Yeah. I’m really excited because when I started out, there was an innocent sort of perception of the world that was coming though me, and I think now through a lot of experience and life and understanding, I’ve come full circle to having a purer response to things. So my craft will be really interesting to work from this place because I think acting is about being in tune with yourself—or maybe the struggle to be in tune with yourself.

CROSLEY: You were very much like your character in Manhattan. She’s very put together and very reserved, a grown-up who’s 17.

HEMINGWAY: Yeah, I think that’s the case. I think talent, especially in acting, is being wholly yourself within the context of yourself. Maybe in any art you have to be wholly you in the context of whatever you’re doing. I think I was innocently myself without even knowing it and projecting a knowledge and an intelligence that I didn’t really have the experience of, but it was there. Now I’m 51, and hopefully I can do it again. I don’t think that anybody, even when they’re playing real character roles, can lose who they are. I think that even Meryl Streep has to find a piece of herself inside the character.

CROSLEY: Speaking of Manhattan …

HEMINGWAY: I know. I was such a kid. I didn’t know who any of those actors were. I mean, nobody knew who Meryl Streep was at the time. And Diane [Keaton] was the nicest person. She was totally fun and I loved her. But it was bizarre: There I was making a movie in New York, and I didn’t really even know who Woody Allen was. I’m like, “This guy’s strange. He’s really nice to me, though.” [laughs]

CROSLEY: He’s like the Jewish James Bond in the sense that you’re like a Woody girl. One of the early ones.

HEMINGWAY: Yeah, exactly. And then I go to the Academy Awards and I don’t even know what that is.

CROSLEY: You didn’t know what the Academy Awards were?

HEMINGWAY: I lived in Idaho. We had three television stations.

CROSLEY: Oh my god, Margaux’s brain must have been exploding, watching you at the ceremony.

HEMINGWAY: Oh, yeah. That was not a good time for her.

CROSLEY: Well, I’d like to say it’s a genuinely lovely film. I think you should buckle up. You’re going to get a lot of people sitting next to you on airplanes telling you their stories.

HEMINGWAY: It’s true. But I also did it for that reason. I don’t think my story is even that extraordinary. When people tell you their story, you’re like, “Fuck. My story is nothing compared to what you went through.”

CROSLEY: Sure, if you’re hell-bent on making it less tragic, at least all seven suicides weren’t in the same generation.

HEMINGWAY: Exactly. Well, I’m honored to talk to you. I’m a fan, so it’s really cool.

CROSLEY: Thank you. They sent in the humor writer to talk about depression. I think there’s the assumption of a sad-clown phenomenon.

HEMINGWAY: I think it’s good. It makes it real.