Remembering Carrie Fisher

Carrie Fisher, a beloved writer and actor, died yesterday at 60 years of age. While her role in Star Wars as Princess Leia (later General Leia Organa) garnered her mass attention and established her as an actor who could be formidable, funny, and earnest all at once, there’s much more to hold dear in the days following this sudden loss, such as her openness as a mental health advocate and refusal to cow to industry standards set for females.

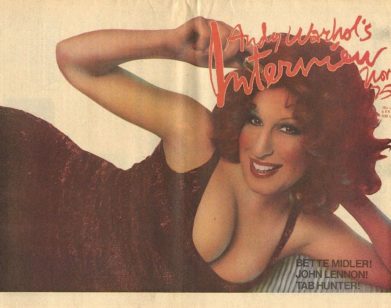

To honor Carrie Fisher’s legacy, we’ve reprinted her September 1990 feature in Interview below. Fisher was 33 years old at the time, at home with her dog and parrots, and reflected on drug addiction, her parents, and her favorite role to date (as well as parrot sex). And, to uphold Fisher’s wishes—as described in her one-woman show and book Wishful Drinking—we must also say that she drowned in moonlight, strangled by her own bra. —Haley Weiss

———

Carrie Fisher By Lisa Liebmann

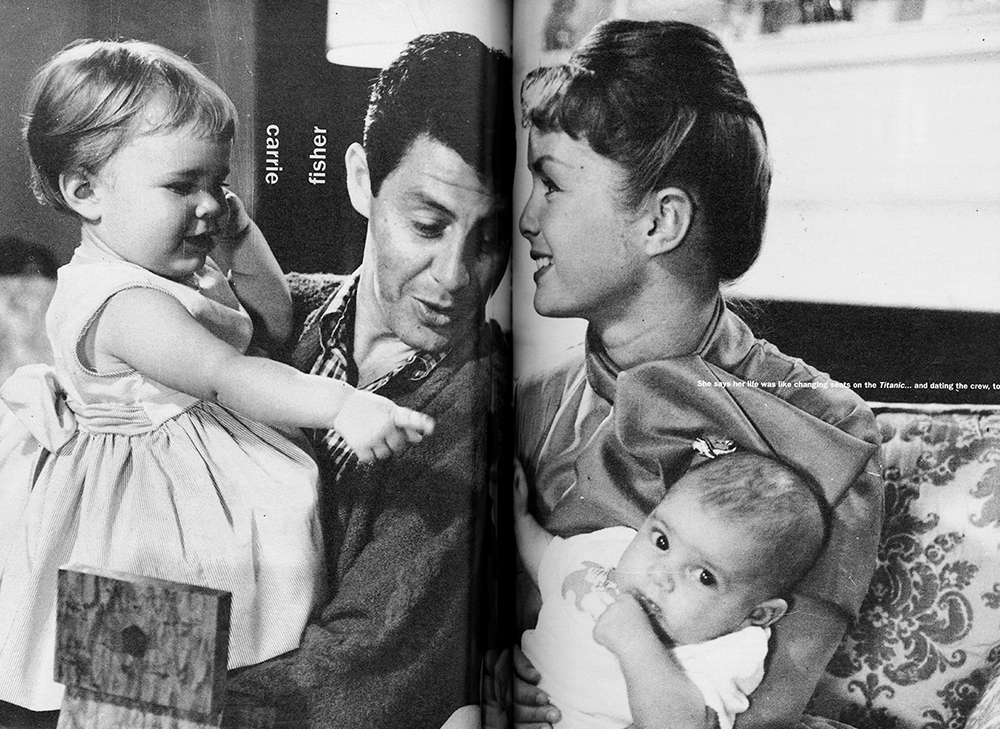

Carrie Fisher is a Hollywood princess many times over. She is an actress whose most notable roles include the sassy Bel Air tennis-court nymphet who seduces Warren Beatty in Shampoo, the mythic Princess Leia in Star Wars, and Meg Ryan’s love-worn but resilient confidante in When Harry Met Sally. She is furthermore the author of the novel Postcards From the Edge and the screenplay for the movie version, directed by Mike Nichols and starring Meryl Streep, due out this month. Her second roman à film, Surrender the Pink, is also due out this month, from Simon and Schuster. Carrie Fisher is a worker. She is also, of course—lest she ever forget it—daughter of Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher, former stepdaughter to la Taylor, and all-around ex to Paul Simon, whose teenage son, Harper, she accompanied on a trip to Eastern Europe this summer.

This survivor of family scandals, star wars, and substance abuse lives in a high-security log cabin on a private road, on top of a canyon behind Beverly Hills. A whimsically Western motif prevails inside and out. The low-slung driveway gate, for starters, is decorated with a brightly painted rodeo scene. Bolted onto it is a little plaque that says: “THE WOW THAT WAS SOME CUP OF COFFEE INSTITUTE OF ALTERNATIVE LIFESTYLES.” I got there at high noon by taxi and was still busy trying to shoo the car and driver away when the fence electronically swung open. Determined to find my way to the house alone, I picked my way along forest path toward a sunny clearing that beckoned through the trees. There I caught sight of the homestead, also of a small, irregular, rock-rimmed swimming pool. Next to the pool stood a big black-and-white decoy cow; from over the fence in some bushes, a second cow was giving me the hairy eyeball. I noticed a tree house with a sign saying “BEWARE OF TRAINS,” and an odd vehicle—something between a rickshaw and a covered wagon—parked on a patch of poolside lawn. The deck chairs were empty.

I looked for a front door to the house, opened it, and had barely enough time to take in a couple of rugged-looking beams, some Navajo blankets, and an open-plan kitchen with a scattering of vivacious Mexican tiles when I was greeted by someone named Gloria, the overseer. I removed my hat, and after a few moments a small figure appeared from a room and started to amble my way. She was gamine-haired and barefoot, wearing dark shades and a loose black T-shirt with kind of an empire line—the definitive schmatte, but fetching. She seemed familiar. When she introduced herself as Carrie and offered refreshment, I asked for a glass of water, and we went outside to talk. On the patio was a fat Jack Russell terrier named Buddy.

———

LISA LIEBMANN: Are we about the same age? I’m thirty-plus.

CARRIE FISHER: I’m thirty-three. We look about the same age.

LIEBMANN: What sign are you?

FISHER: Libra. And what sign are you?

LIEBMANN: Taurus, which would make me five tree seasons your senior. I’m from the Northeast, so I keep track in terms of the changing leaves.

FISHER: Really? I keep track in terms of the wrinkles. Especially near the eyes and down around the mouth. They do tend to start showing up at around this age, but then there’s always a little something between you and the way you’d like to look—five pounds, or hair to grow out, or something. Both of my parents, for instance, have had face-lifts.

LIEBMANN: How are your parents?

FISHER: They’re actually quite well, thank you. My father just got out of the Betty Ford Clinic. He’s in his 60s, and this was the first time he ever did anything like that. I was very surprised. Not him, I thought, and why now? I mean, for years he’d been doing everything imaginable … from speed to downers to you name it. I used to call that “changing seats on the Titanic,” and I used to say that I myself was not only changing seats on the Titanic but dating the crew.

LIEBMANN: What do you think made your father go to Betty Ford?

FISHER: He’s with a woman now who doesn’t do any stuff, and I guess that had something to do with it. Generally someone will eventually tell you that you have to do something to help yourself.

LIEBMANN: Do you do any drugs at all now? Even in a minor way?

FISHER: Nope. Nuthin’. But it’s certainly around. Actually, social drug-taking went kind of low-key for a couple of years. Probably because of AIDS, people got very conscious of their health. But it seems to be making a comeback. Just the other night I was at a party where people kept disappearing into the bathroom every few minutes. I’m glad I did all that in my 20s and that I’m done with it. And that I wrote about it in Postcards from the Edge. I’m really grateful that I could write. But I don’t even mind it going on around me. I actually even sort of enjoy it. I mean, most fun things are bad for you in one way or another.

LIEBMANN: Even caviar…

FISHER: I hate caviar. Ugh! The freebase of food! My mother certainly loves it, but I think that’s generational—they grew up thinking it’s romantic or sophisticated or something. All I know is that you can chop up all the onions and the whatevers you want and put it on top of it, but you still can’t disguise the fact that you’re eating fish eggs. Ugh!

LIEBMANN: Caviar really goes best with booze, I guess with champagne or vodka. Do you ever drink?

FISHER: No. Never. I guess, as they say, I never acquired a taste for it. So asking me if I quit drinking is a little like asking me if I quit having orgies on network television or something. I love all those romantic, kind of southern words—like “libations”—for getting fucked up. But I took “medicines,” strictly. Drugs. I liked the ritual of it. I like the illicit community of it … all those lucky, lawless men.

LIEBMANN: Do you miss all that?

FISHER: Of course I miss it. And anyone who tells you they don’t is lying. I used to want to gamble, too, until I was 20 and could actually go to a casino. Then I wasn’t so crazy about the attitude. You know, O.K., I’ve got 50 dollars to lose. O.K., I’m an asshole! It seems you have to play big to win big, and there was just too much risk. It’s the same principle when it comes to dope. But I liked the idea of getting away with shit.

LIEBMANN: Ever try shoplifting?

FISHER: No, nor did I go out with married men.

LIEBMANN: Is your mother married?

FISHER: As a matter of fact she’s very happily married. To a very nice southern gentleman named Roanoke—her first non-Jewish husband, as she likes to say.

LIEBMANN: In Surrender the Pink, every time the main character suffers even a growing pain, her mother says to her, “It’s that Jewish thing, dear.” Was that your own experience?

FISHER: [laughs] You bet. She said stuff like that all the time. I’ve often said to myself, “Thank God I can write, ‘cause this is hilarious.” I actually wanted to go into all that more in the book, but my editor thought it was too crazy.

LIEBMANN: Do you think of yourself as more Jewish, or more not, or neither?

FISHER: I always felt the Jewish part more. In fact, growing up I felt like a Jew among WASPs. My brother is more decidedly Waspy.

LIEBMANN: Are your father’s parents alive?

FISHER: I never really had anything to do with them. My father’s mother is alive, or as he puts it, “She’s alive but howling.”

LIEBMANN: How about your maternal grandparents?

FISHER: He’s dead but she’s very much alive. They were from Texas. El Paso. White trash.

LIEBMANN: I was given bound galleys of your new book, and in my copy I noticed the dedication is to your maternal grandparents and your father but not—

FISHER: I changed that, I changed that. Now it’s dedicated to my grandparents and to both of my parents. The first book was dedicated to my mother so I thought maybe it was my father’s turn, but then I realized that everyone would jump on that and assume I’d had some falling out with my mother, which is absolutely not the case.

LIEBMANN: Are you close to your mother?

FISHER: God, until adolescence I thought I had the best mother in the world. Such a graceful mother. I had this fantasy that I was the wrong daughter. And believe me, I didn’t think there was some princely family I belonged to. I thought it was like a toe—the offspring of some strange cult, a wrong adoption. My father had fucked up my mother’s money and stuff, but my mother was always so pretty, so perfect. Then, when I was 15 and she was 39, her second marriage broke up and she went into a crisis for the first time since my father left. I had this idea that I wanted to help get her over this crisis. It was very frustrating. I didn’t want the crisis, I wanted the graceful mother back. Well, I got her back in about five years. [At this point a compact green parrot, unescorted, lumbers out of the house toward us. Dean is intelligent, intensely sociable, and remains on Carrie’s lap or arm, sipping Coca-Cola from her can and nibbling the Saltines she feeds him throughout the rest of the interview. The black T-shirt soon becomes a very soiled parrot nappy.] Anyway, all my life I’ve been seeing things through the culture. My father, for instance, was the press’s bad boy. People really hated him. He was always a big flirt. He was always in trouble—going bankrupt, whatever.

LIEBMANN: But I gather you’ve reconciled or gotten back together with him in some way.

FISHER: Kind of. I never really saw him at all when I was growing up. When my brother, Todd, was born my father was already with Elizabeth. I was 19 or 20 when I first spent a block of time with him.

LIEBMANN: Where was that?

FISHER: New York City.

LIEBMANN: Were you “bad” together then?

FISHER: Yeah, I guess there was acid… I dunno…

LIEBMANN: That’s kind of interesting and unusual for a girl. It’s often considered a normal rite of passage for a boy to go out alley-catting with Dad. But you don’t often hear about anything like that with girls.

FISHER: I know what you mean. But I don’t want to go into that very much. You should really talk to Jamie Lee Curtis about that sort of thing… [Suddenly, and as if by design, Gloria appears holding Joan, a second, less social green parrot. She hands Joan over to Carrie and goes back inside.]

LIEBMANN: You’re big on animals?

FISHER: I like birds and dogs. I’m allergic to cats. I have a second dog, too, mainly for security. He’s in military dog school right now. The parrots are great. They do something I refer to as “the Phone Call from Venus.” They repeat all my phone conversations. It can very annoying—like having a lot of children in the house screaming. Plus, Dean’s maybe too young to impregnate anyone, but they do fuck. Many mornings I wake up to the noise of parrot sex echoing through the hallways. Joan likes to come visit me while I’m in the tub. She sings opera, too—because of Gloria and the radio. Look. [She gives Joan a sip of Coke from the can.] When I was in the Amazon I saw a parrot who drank beer from a can.

LIEBMANN: What were you doing in the Amazon?

FISHER: [offhandedly] Oh, visiting…

LIEBMANN: [laughs]

FISHER: I don’t do acid anymore, so I travel instead. [She strokes Joan’s top feathers.] Look at this—they really love this. That’s because their vaginas are on their backs.

LIEBMANN: No kidding? Let’s talk about movies. Which of your movies was your favorite?

FISHER: [without a second’s hesitation] The ‘Burbs.

LIEBMANN: Really!

FISHER: Yup. It was just great. Tom Hanks was really great. The director, Joe Dante, was wonderful. We filmed it here during the summer, every day at Universal. Even the food was good—I mean it was junk but it was really good. The whole thing was like some ideal summer-school experience. It may not have been the best movie ever, but it was certainly the most fun.

LIEBMANN: What about When Harry Met Sally? It sure seemed congenial.

FISHER: Yeah, sure. It was fine, but it was a job. And I did it right after The ‘Burbs. Meg Ryan was nice … the writing was good … but it was really kind of a boy’s club, I mean, there was Bruno Kirby, Rob Reiner, Billy Crystal—talk about your testosterone trio!

LIEBMANN: Rob Reiner recently married my old childhood nemesis.

FISHER: What do you mean?

LIEBMANN: My chief torturer in the sixth grade—it was a bad phase, but she was the worst. We were in the same class for eight long years. Her name’s Michele.

FISHER: Oh, yeah … I know who you mean. They met on the set of Harry Met Sally.

LIEBMANN: I think she’s a photographer. A couple of months ago I was on a plane reading an article about Gerard Depardieu in the in-flight magazine, and the picture had her photo credit on it.

FISHER: Do you ever see her?

LIEBMANN: Every few years or so I run into her somewhere. Most recently, maybe two years ago, we actually got haircuts together—just the two of us, in twin parallel barber chairs, in a little side room of the salon, getting worked on simultaneously—and we didn’t exchange a word. It was fun, to be quite honest. I suspect we both enjoyed it. We just kept eyeing that mirror. It didn’t seem particularly nasty anymore, just funny and sort of reverse-macho.

FISHER: I had someone like that, kind of. This actress named Lisa Eilbacher. I was up for the part in Shampoo and friends of mine kept telling me she was going around saying all these bad things about me. It’s like we’re still in the sixth grade sometimes.

LIEBMANN: But you got the part.

FISHER: Yup. I got the part. But it was this very unpleasantly rivalry tug.

LIEBMANN: Do you have a preference between acting and writing?

FISHER: I like having written better than I like having acted. But I like the community of acting better than the prison of writing. I like sets. What I really like is the marriage of both—for instance, with Postcards. I don’t actually act in it, but I worked on it with Mike [Nichols] as I went along, creating the character, so it was a bit like acting for me.

LIEBMANN: Meryl Streep is the you-ish character?

FISHER: I like that—the “you-ish” character. Yes, Meryl plays the me-ish character. I love Meryl. She’s totally wonderful.

LIEBMANN: Has it ever occurred to you that you and Nora Ephron by now really have Meryl between you? That it’s almost as if she’s become your joint, alternative id?

FISHER: [laughs] I hadn’t stopped to think, but I guess there’s something to that.

LIEBMANN: Are you doing a screenplay for Surrender the Pink too?

FISHER: Yes.

LIEBMANN: Is there a deadline?

FISHER: There certainly is. October. But I’ve never met a deadline I couldn’t miss. I make sure my editors know this.

LIEBMANN: I have to mention something. I read Surrender the Pink—pretty fast, I admit, but I did read it—and I didn’t notice any reference to the title in the actual pages of the book.

FISHER: That’s because there isn’t one.

LIEBMANN: So where’s that title from?

FISHER: A story a friend told me about being in New York and meeting this Latin-lover kind of guy. They went up to her hotel room, and the guy kind of pounced on her and told her to spread her legs, shouting, “Surrender the pink! Surrender the pink!” That’s where it’s from.

LIEBMANN: Who do you picture as the you-ish character in that movie?

FISHER: I always think of Meryl for everything now. There really aren’t many actresses around who are truly lucid the way she is. Oh, I guess I could Debra Winger in any number of things. She’s so luminous—it’s a birth defect.

LIEBMANN: Surrender the Pink is mostly about women in relation to men—absent fathers, powerful or self-absorbed husbands and lovers—but there’s a strong female best friend character who is a perpetual kvetch. She’s like a nightmarish embodiment of mega-girl talk. She constantly talks about her periods. When you were writing that kind of literal-minded character, did you worry at all about sounding like that kind of literal person?

FISHER: I have a girlfriend who talks like that all the time. Don’t you have friends like that? Who constantly complain about their periods and plumbing and stuff?

LIEBMANN: Of course, but it usually makes me want to retreat from my entire gender. It’s a bit the same with stereotyped, self-deprecating “Jewish humor.” It brings out the prude in me. I know it has its virtues, but I guess I’m just not too big on that kind of bonding.

FISHER: I know what you mean. I can’t say that period talk is my favorite bonding arena. But I also think it’s sort of funny. I probably have more male friends that talk about us in a way that doesn’t thrill me. I sometimes get a bit surprised when females talk like that around men.

LIEBMANN: I think I prefer that to having women friends talk that way to me. Around men that kind of talk’s a bit more interesting—more psychologically telling. You get to see a bit of cause and effect. It has a certain radical edge to it.

FISHER: It is sort of radical. Confrontational. They do that sort of thing a lot in A.A. People get very competitive and confrontational about bottoming out. You know—I’m worse therefore I’m better—all that sort of shit.

LIEBMANN: Is A.A. a popular bonding arena in the entertainment business here?

FISHER: Sure. Finding the cutest guy in A.A. is like finding the cutest loony in the bin. But at least you know what you’re getting. You’re not surprised when alcoholics act like alcoholics. It’s more surprising when non-alcoholics start acting like alcoholics.

LIEBMANN: What do you think of Madonna these days?

FISHER: I don’t like the masturbation stuff. I think men go for that more than women. It’s like Elvis Presley taking his dick out in Jailhouse Rock—you know, not actually taking it out but indicating its whereabouts at all times. But I say more power to her, though I don’t know how much more power is out there.

LIEBMANN: Have you ever formally studied acting?

FISHER: I went to drama college in England—the Central School of Speech and Drama, in London. I was there for not quite two years, then I got Star Wars.

LIEBMANN: I’ve always been curious about what it was like for you to act in the midst of all those effects. I mean physically. What were you doing? How were you and the other human actors actually filmed with all that stuff going on?

FISHER: Against a blue screen.

LIEBMANN: That simple? You mean you were just going through your dialogue and moving around on a soundstage with an empty blue screen behind you and that’s it?

FISHER: That’s it. A blue screen. All the rest came later, in Lucasland. They did have me take gun lessons, though. I went to the same guys who taught Robert De Niro for Taxi Driver.

LIEBMANN: Have you ever had the occasion to use those skills again?

FISHER: [laughs] No. Well, I had to shoot shotguns for The Blues Brothers. But I don’t like that stuff. Too butch for me.

LIEBMANN: Do you like butch qualities in men?

FISHER: I must say I can appreciate it when males are very male. Like Harrison [Ford], for instance. He’s pretty butch. I guess I prefer butch to terribly fey.

LIEBMANN: I like ‘em on the fey side myself.

FISHER: I can like men who are a little light in the loafers.

LIEBMANN: [laughs] I love that expression…

FISHER: If some gang were threatening your family, you’d go looking for someone butch to help, right? Any maybe if your mother were sick or something, you’d find someone a bit more fey.

LIEBMANN: I dunno about that. If some gang were threatening my family, I’d think twice about calling in some super-butch man for help. He might aggravate the situation. I’d probably handle it better myself. Sometimes a bit of psychology does the trick, don’t you think? A little sweet-talking à la Jimmy Stewart, perhaps.

FISHER: I see your point. I guess high verbal skills are highest in my list of necessary qualifications for a man—for anyone actually. I like to talk. And I don’t necessarily move far, but I move fast.

LIEBMANN: You’ve been married once, right?

FISHER: Right.

LIEBMANN: Can you see being married again?

FISHER: I suppose. But I don’t really understand it—marriage. Still, the word “boyfriend” starts to sound pathetic after age 30.

LIEBMANN: Your new book ends up cynical about this subject, but in a hopeful sort of way. Is that how you feel?

FISHER: Well, I don’t think 50-50 relationships exist. Men have an incredibly variety of options. It’s much harder for a woman to do both things. I think traditional relationships work best. I grew up with the idea that I was supposed to have the bastard children of great artists and powerful men or something, and count myself among the courtesans. Then the rules changed mid-stream, but I still think great artists are the most interesting.

LIEBMANN: Like who?

FISHER: Like my ex-husband. But you have to constantly arrange yourself around them, and that can take up a lot of energy. I mean, you don’t go, “Why don’t you cook dinner tonight, dear, for a change, instead of writing a great song? I loved what he did with words. But I wanted to do some more of that, too.

LIEBMANN: How about a handsome young carpenter? Maybe that’s less stressful.

FISHER: [laughs] Come to think of it, Harrison Ford used to be a carpenter, you know.

LIEBMANN: As is, you certainly seem like the King of the Mountain.

FISHER: Oh no! Not that! At least make it king of the Hills! I guess I do carry a bit of male energy. It’s like what I always say—two yangs don’t make a right.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE SEPTEMBER 1990 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.