Blake Butler’s Waking Life

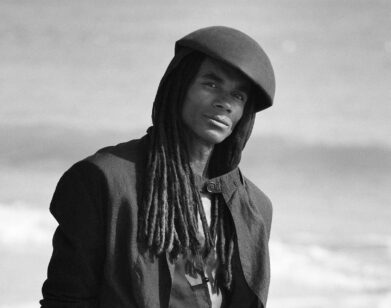

BLAKE BUTLER. PHOTO COURTESY OF HARPER PERENNIAL

Anything’s possible in dreams, from flying to Inception. But in Blake Butler’s somnambulist memoir Nothing (Harper Perennial), sleep and dream states take on a more disturbing quality. Plagued by insomnia, night terrors, and sleepwalking since his youth, Butler explores the space between sleeping and waking and what happens when that line is blurred.

Butler writes in lush, lonely prose, hallucinating that his mother was a stranger; trying to understand his father’s dementia; experiencing his first nightmares and isolation. Butler also delves into the history of sleep—the cousin of death—and the figures inhabiting his insomniac thoughts, from Andy Warhol to Stephen King. It’s a deft exploration and dictionary of dreams, whether they push our imagination to greater accomplishments or become haunting images playing over and over on the inside of our eyelids. We spoke with Butler about his busy brain, Ripley’s Believe It Or Not, grocery store etiquette and where he’d sleepwalk, if he had a choice.

ROYAL YOUNG: Did you have a good night’s sleep?

BLAKE BUTLER: [laughs] Yeah, it wasn’t too bad, actually.

YOUNG: How would you explain insomnia to someone who doesn’t have it?

BUTLER: There are lots of different kinds, or ways that it starts, but I guess it’s the inability to go to sleep when you feel like you want to. That’s a functional definition. It’s like you’re tired, you want to go to bed and your brain won’t stop working, which is my problem.

YOUNG: When you say your brain won’t stop working, what do you mean?

BUTLER: When you lay down, your head is spinning. It’s kind of like when you’re drunk, but when you’re drunk it’s more abstract feeling. With me it’s the most inane thoughts just won’t stop going around my head. And the more you try to stop, the harder it is, like your brain is fighting your body.

YOUNG: So you’re not thinking about the big life questions? You’re not laying there, like, “What’s going to happen when I die?” it’s more like, “Fuck, I have work tomorrow at nine.”

BUTLER: Right. Or even more mundane than that, like, “Should I have gone on Facebook and ‘liked’ that comment?” Or, “Did I lock my car?”

YOUNG: But there are nights these thoughts don’t plague you?

BUTLER: Yeah, things have been a lot better recently. Especially since I wrote the book, I worked through some big things I’ve been working on for awhile. I’m able to chill out. But I still don’t go to bed till like 3 or 3:30 am. To me, that’s normal.

YOUNG: Where do you think it comes from? Do you remember a time when sleep wasn’t an issue, or any inciting incident that triggered insomnia in you?

BUTLER: I don’t really remember it ever being different. My mom is the same, so I think I got it from her. I remember as a kid, renting this series of “Ripley’s Believe It Or Not” videos and there was one where this guy was haunted. They filmed a reenactment of it, so this guy was just sitting in his living room and this shitty-looking ghost, which was an overexposed image of a person, comes walking in. It scared the shit out of me. It was the first time I knew ghosts could exist. That taught me the world was more complicated.

YOUNG: So your perception that there were more layers to reality and that they were scary?

BUTLER: Right, or that things could come through the walls of my house without me knowing it was there. It was fear without an object.

YOUNG: Fear of the unknown?

BUTLER: Yeah, like when I checked Stephen King’s It out of the library and didn’t know anything about it, except that it was a terror object. I took it home and never even opened or read the book, I just sat it on my desk and it scared the shit out of me that it was even in the same room.

YOUNG: If I felt that way about a book, I would always put it face down, cover down. I felt it diminished its power.

BUTLER: [laughs] Exactly! That’s how it works.

YOUNG: What do you think the world does when we’re asleep?

BUTLER: Often when I go out at night when I’m supposed to be asleep, like if I go to the gas station, it feels like a video game. Like a role-playing video game where there’s this person waiting in a supply room for you to buy shit like potions or a broadsword. That’s what I always picture when I’m in my room and start thinking about things outside the house. There are things going on out there waiting for you to run into them.

YOUNG: How has your young feeling that your family were strangers, that your mom was unknown to you in your sleep states, affected your later life?

BUTLER: One of my first memories is my mom trying to get me into the bathtub and I was standing in the kitchen bawling, because though she was probably ten feet away from me, it seemed like she was a hundred feet away. She had this very calm, patient look on her face, but for some reason the way the light was made her seem like some alien. That distortion carried over into a lot of people. I’m really close to my mom, but things with my dad have been different. He has dementia and watching him change, I’ve actually started to think that it’s a purer state for people. Because he operates as if he’s a child and everything is new, which seems more honest.

YOUNG: Going back to your mom, that distance, distortion and people in the night being like video game characters—you seem to have this remove from people.

BUTLER: Yeah, that has definitely been one of the biggest things that has welled up over time. I feel like I talk to people less. When you’re up that late and you spend most of your time quiet and the world seems to be all asleep except for you, you kind of start retreating into yourself. Which reinforces the busy brain thing. It makes daily life when it’s light out really confusing. It seems weird to go to the grocery, because the lights are always on and people are always there. Like another part of the world that never goes to sleep. Like being in a zombie state.

YOUNG: I hate the grocery. It’s too bright.

BUTLER: [laughs] I actually feel kind of comfortable in there. It’s a place where no one talks to you. It’s really fucking weird when people in the grocery talk to you. It’s like, this is a zone where we all have a goal, and no one talk to anyone. But, yeah the light makes it a little strange, like you’re in a test chamber.

YOUNG: Which are harder to cope with, dreams or reality?

BUTLER: Definitely reality. I have really bad nightmares, but I actually love nightmares. I kind of love dreams, no matter what happens in them. Reality is not much fun comparatively. A lot of our days are just dealing with mundane shit like email.

YOUNG: If you could sleepwalk anywhere, where would you go?

BUTLER: I think I’d like to go to the mall. But I’d probably still be naked, so I’d probably get arrested. Maybe a water park. A water park at a mall.

NOTHING IS OUT NOW.