Why Did a British Artist Trace Every Inch of Ian Curtis’s Former House?

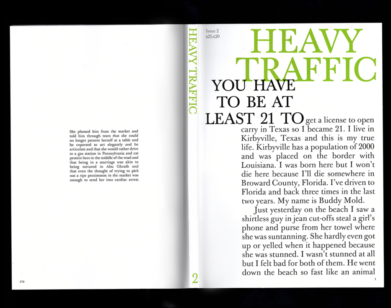

77 Barton Street’, 2019, wax frottage on paper, 563 x 504 cm, courtesy of Herald St, London. (Photograph: Reece Straw)

77 Barton Street’, 2019, wax frottage on paper, 563 x 504 cm, courtesy of Herald St, London. (Photograph: Reece Straw)

For the Deichtorhallen art center in Hamburg, Scott King has made a wax rubbing of Ian Curtis’s home in Macclesfield, UK. For two days, the British artist worked with a small team to trace every inch of the exterior of 77 Barton Street, the site where the Joy Division frontman lived with his wife Deborah and their daughter before committing suicide in 1980. King’s tribute to the site, which has become a destination of sorts for fans of the post-punk band, is the latest addition to his commentary on rock iconography. Interview’s editorial director spoke with King about the rock and roll iconography, the religiosity of a wax rubbing, and the ubiquity of Joy Division apparel.

———

RICHARD TURLEY: What came first: the idea to do a wax rubbing or the desire to capture and document the house?

SCOTT KING: I’ve had the idea to make a rubbing or frottage of the façade of 77 Barton Street for a very long time. I can’t honestly say when I first thought of it, or even how. I had to think very hard about doing it because I didn’t want offend Ian Curtis’s family or friends. I wrote to [his widow] Deborah Curtis to explain what I wanted to do but never heard back. I suspect she is inundated with all sorts of odd requests. In the end, I decided to do it. I knew that I wanted to make something monumental and celebratory — something that also spoke about the background of Joy Division – about how this great art, these great lyrics, were written by a young man in a small house in the North of England.

The idea of doing it as a rubbing is really about reverence. Stone rubbing is an ancient art form that originated in China thousands of years ago, although many of us mostly associate it with childhood. I remember doing it on a school trip to York Minster, placing a piece of paper over an engraving, then rubbing a wax crayon over it to make an image of the surface beneath. It has a kind of inherent religiosity to it. It’s a devout act. By making a rubbing of the house, I was making a parallel between religious and rock iconography. I wanted to apply this form of art making – one we might more usually associate with cathedrals or “official history” – to this terraced house in Macclesfield. It was amazing how many people came to look at the house in the two days we were there – fans who’d travelled from France, Italy and Germany. It made me realize that 77 Barton Street is already a very public place – an unofficial monument – so I felt more confident in what I was doing because it felt less intrusive.

TURLEY: With wax rubbing you’re also basking in the melancholy of youth. In some ways, it feels the most Scott King work to date. It’s also a really big, house size. It’s theme is music and loss. It’s also a sort of public art. Is this the King masterwork? The key piece?

KING: Well, I’m very flattered you might think it a “masterwork.” I first made a piece of work about Joy Division in 1992, when I was at college, so it’s been an on-going theme. That said, lots of artists have made work about Joy Division and Ian Curtis. It’s considered a cliché by some. Then again, these are the same people that might get excited about another piece of neon in an art gallery. It does bring a lot of things together for me, as you mention: melancholy, pop music, architecture and public sculpture. The funny thing is, I was really miserable at the end of last year — I had nothing much going on and was full of self-doubt — having done this I realized that I was miserable because I wanted to be popular or something. But it isn’t about that. If you truly have a need to do something, write a song, make an artwork, or whatever it is that you obsess over. You have to do it.

77 Barton Street. Macclesfield, England.

TURLEY: There’s obviously a through-line from Kurt Cobain’s lighter to this rubbing. But whereas the lighter felt like it was mocking our idolization of people such as Cobain and Curtis, this feels less acerbic, far warmer and more generous to the subject.

KING: I hadn’t thought about the connection between this and Kurt’s Lighter – but I think you’re right. The video was mocking fandom really. Specifically, middle-aged men, like myself, who cling to the minutiae of musical history in the form of artifacts, lost tapes and personal memories. It was about that very male thing of becoming a self-appointed pop archaeologist. Living in someone else’s past in fear of your own future. This, however, is very different; among other things it is a genuine, and maybe quite extreme, act of fandom.

TURLEY: How did it feel standing outside Curtis’s house?

KING: It was confusing. On the one hand you know what happened here – Ian Curtis’s death and how terrible that must have been for his family and friends. It was impossible not to think about that and be respectful of it. On the other hand, and to most people, it’s just a house. Lots of people wanted to talk to us, ask us what we were doing. The first person who spoke to us — well, shouted at us — was drunk. It was about 10 A.M. on Saturday morning, and he was on his way to the pub. “Are you scousers? You must be scousers! Nobody else would wallpaper the outside of a house!” And I thought, “Oh god, it’s going to be like this all day.” But the neighbors were nice. We were warned that one of them, an old man, hates all the fans turning up, and would likely shout at us: “Fuck off with your Blue Division!” But we never saw him. It was all very humbling really, some of the locals had known Ian Curtis of course — so, it wasn’t something we did lightly.

The house is very much part of the story. Not just because Ian Curtis died there, but because he also wrote there, he lived there with his family. That’s the great dichotomy I think — having rock and roll dreams while still trying to lead an ordinary life. I think that’s really it for me, what the house symbolizes — this kind of dreaming and the need to do something. When you see footage or photographs of Ian Curtis performing, you can see that he wants to be Iggy Pop or someone — that he wants to emulate his heroes and wants to be “up there.” In many respects, he was just this working-class lad from Macclesfield — yet in lots of ways he far surpassed his heroes.

The art work in progress.

TURLEY: The tragedy of Ian Curtis’s suicide is inescapable. But it feels especially sad that the guy didn’t live to see the endurance of his music and the often surreal legacy of his band. Everybody’s got a Joy Division T-shirt – I even saw Unknown Pleasures yoga pants a little while ago. Raf Simon’s continuing idolization of Joy Division, New Order and Peter Saville. There’s been movies made about Ian Curtis. Hooky’s singing his words in university towns with the backing singer from the Happy Mondays. What is it with Curtis and the stories we tell ourselves about that band and that moment in culture that still compel us?

KING: It’s amazing isn’t it? Especially the low-end products and endless interpretations of the Unknown Pleasures graphic. Now, you really can buy Joy Division oven gloves, pencil cases, and socks. I see it as “product authentication,” not to be confused with an “authentic product.” The bottom line is Joy Division are very influential. They have always been seen as “cool”. and I suppose people believe that by transferring the imagery associated with the band onto products, therefore the owner of these things will become cool as well. It’s an epidemic of signs really isn’t it? Imagery being passed from its original context into a mass, off-the-peg, symbolism. In the end, you can’t stop people liking stuff, can you? Joy Division looked like a band that had been designed by Samuel Beckett, and that kind of austere, brutal, minimalism, that hard modernity, will always make them very attractive.

‘77 Barton Street’ was commissioned by Deichtorhallen Hamburg and curator Max Dax. It will appear in ‘Hyper! A Journey Into Art and Music’ at Deichtorhallen Hamburg from 1 March – 11 August 2019.