Web Life: Q+A With Peter De Potter

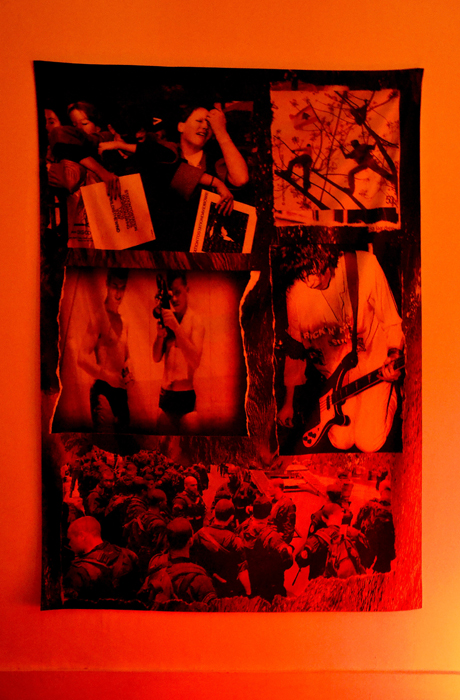

Belgian artist, writer, and curator Peter De Potter’s latest series of works (“…collections of images, each series dealing with another idea or aspect”) is titled “Angelic Upstarts.” Comprised of 50 collages and published exclusively online, each work bears a handwritten idea or value he considers “important in life.”

“Upstarts” is the third full series he has presented—exclusively online—since we began our dialogue. It’s a far cry the format I first saw his work in, nearly a decade ago, when I picked up the fashion designer and long-time collaborator Raf Simons’ curated “The Fourth Sex” book. Housed in a print format, it’s a thoroughly researched collection of everything youth culture, and its struggle against the sexless homogeny that the “adult” system of commerce and consumption cultivates. De Potter’s thoughtful eye helped point the tone of the curation to a true understanding of how teenagers, especially, create subcultures around specific media, sometimes subverting what they inherit, and at other times falling square into the trap of cynical creative directors who understand how to commodify those same things for different gains. If the narrative then pivoted on records, television, and film, I asked De Potter how it has changed now.

HARSH PATEL: How did you begin to work with Raf Simons?

PETER DE POTTER: I started to collaborate with Raf around 2001, mainly providing my art or words or visuals to use on his designs, invitations and corporate imagery. The great thing about our collaboration was that he also got me involved in other projects that came on his way, like “The Fourth Sex” exhibition and the accompanying book. “The Fourth Sex” was particularly exciting because Raf co-curated it with Francesco Bonami, and because it aimed to show the complexities of the theme of adolescence, doing away with the propaganda-like cheerfulness that is so often associated with the subject.

PATEL: You were credited as “Research Coordinator” for that exhibition.

DE POTTER: My role in the team was to come up with examples and visual quotes from the more hidden layers of pop culture—not so much cult, more the unsung heroes, the little gestures, the B-sides, if you will. I think the book still holds up very well—as a little antidote, perhaps, for the barrage of “youth” imagery that thinks big smiles, floppy hair, and some ironic tattoos are all it takes to portray a demographic of millions and millions of different people and different minds.

PATEL: Could you tell me a little bit about [the video-based exhibition] “The Young Gods,” from around this time?

DE POTTER: The year after that, I was invited to curate a solo-spot for this other exhibition promoted by Pitti Immagine called “Excess.” It was about the revival of the ’80s. For the exhibition, I ditched the idea to show clothes—never!—and made a video installation instead: three monitors, three separate videos playing simultaneously, called “The Young Gods.”

PATEL: What was your time at the Royal Academy [of Antwerp] like?

DE POTTER: Going after an art education equally has to do with this artistic bug inside of you that just won’t go away, as well as wanting to escape the surroundings you grow up in—it’s this classic story. When I was 18, I found myself dulled in a little provincial town—all monotony and mundane events, while all I wanted was to grab the master key to Andy Warhol’s Factory. Neither the Academy or Antwerp turned out to be particularly controversial, but that didn’t matter one bit. One thing I like about art schools is that there is always this barely-concealed competition in “being different than the rest.” It’s almost a cliché—and in the process, a lot of people may end up looking or acting like one… but it can be a great exercise in self-education. It’s also there that I learned that having a deep, almost religious love for images is not a waste of time, per se.

PATEL: How do you feel about Antwerp now?

DE POTTER: I can’t really say Antwerp has influenced me or my work in any way at all—apart, maybe, from a few people who incidentally live here as well. Like most relatively small cities, Antwerp provides you with pretty much everything, but always in pretty small doses, so there’s never this feeling of complacency or overkill. People from, say, New York or London find it really strange that a micro-city like Antwerp can produce so many world-renowned designers and artists, but the real explanation is that they all refuse to move, they all keep living here instead of spreading out. Maybe doing it from the home is a Belgian thing, I don’t know.

PATEL: Which fits with the idea of using a blog to share work with the world. I feel a little bit alone in seeing the traditional constructs (galleries, superstar curations) as a bit less relevant.

DE POTTER: I think any artist should try to be as modern as possible, not so much as a statement, but as a way to facilitate the communication with the viewer. The Internet can be a useful platform, or even the most obvious one, since virtuality has become part and parcel of everyday life. I guess we are all coming to terms with the fact that the Internet is one huge, barely-controllable image machine. And it has brought along a new approach to imagery in general: less reverential, more loose. Regarding the collecting aspect of my work, I think it’s true that archiving—or collecting, or serializing—is this solitary, sometimes neurotic activity; but it also serves a purpose, in some ways an almost heroic one. In the same way the medieval monks archived their monastery garden by drawing every plant and seed and beetle in huge books, some of the bloggers and Tumblr people equally try to preserve and come to terms with the vast and ever-growing amount of images history has ever produced.

PATEL: It means great things for young people, too, I think. They inherit less baggage and get to find and arrange things, to tell whatever story they’d like.

DE POTTER: I think it’s a wonderful thing, actually. I feel very connected to that idea, because it’s what I have been doing all my life! I think the current social-network sites are very important, because they are closest to life itself and always speak of the now, never of the past. Those sites are bottomless wells of beautiful imagery, but not in the oh-it’s-so-vulgar-and-plain-I-postmodernly-love-it kind of way. I am completely serious when I say that I want to save a specific portion of those images from oblivion; it’s a huge, huge part of what I do. It also fits in with the fact that I think artists should show life instead of their own life—and I mean that quite literally: showing life, divulging life, rather than “reflecting” or “examining” it. There is this snobbish notion that people, and young people in particular, are totally lazy when it comes to imagery—one click and it’s done—but I find that people present themselves in extraordinary ways on the Internet, very fascinating and very beautiful and with a very clear vision of how they want to show themselves. Totally erasing the fine line between amateur and professional, and between vanity and honesty.

PATEL: Does the source material for your recent pieces have a specific thematic pivot point?

DE POTTER: I never use the term “source material,” because the material is the work. When I do a collage, it is never to illustrate a point or to visualize a statement. It’s the image that takes over and dictates, as it always should. The image is the muse, it’s as simple as that. In my work, there are a lot of images that I think should be shown on a bigger platform and even should be held in high esteem, but for some reason or other are not. Not so much because they get rejected, more because they are… forgotten or overlooked. A lot of the time the material centers on masculinity, mostly because over the years I have become very intrigued with how men are portrayed and how they care to portray themselves. I try not leave anything out. There are the typical totems—drinking, fighting, wandering, hunting. But there’s also male vanity, male docility, male envy, male gentleness, all in one.

PATEL: Is your work part of any particular lineage, then?

DE POTTER: I’m not sure if I fit into any -ism, but that’s beside the point, at least to me. All art that I find relevant seems to be before all about choosing “the right picture,” for whatever reason the artist him- or herself can think of. Warhol, Tuymans, Baldessari, Richter, Cady Noland: all very different artists, but all of their work triumphs or fails with the choice of the core image they want to communicate. I mean, those are just a few contemporary names, but museums all over the world are stuffed with the great masters of past centuries, and it’s exactly the same process. All paintings and sculptures where the artist before all has chosen the right image, the right scene. That particular girl, that particular landscape, that perfect sunset. It’s in the choice of the image that an artist can show his or her genius or—if you will—incompetence, and the rest is up mostly to technique. But that’s already quite an academic answer, because there is no use, no point when an image, found, stolen or self-made, has no emotional value, or any feeling for want of a better word. All the images I use should have that, because when there is feeling, there’s beauty, not the other way round—although the images I take on are sometimes very, very specific, about very specific situations and a very specific kind of people. Strangely enough, I find the more specific they are, the more universal my work becomes.