Stories in a Shoebox

The notion of pulling a shoebox out of a closet, wiping off dust before opening it and exposing old Polaroids, is a romantic one. For New York-based set designer Happy Massee, this experience consisted of 25 years worth of images, and prompted more than a private review of his past; he decided to edit his photographs into an art book titled Diary of a Set Designer (Damiani).

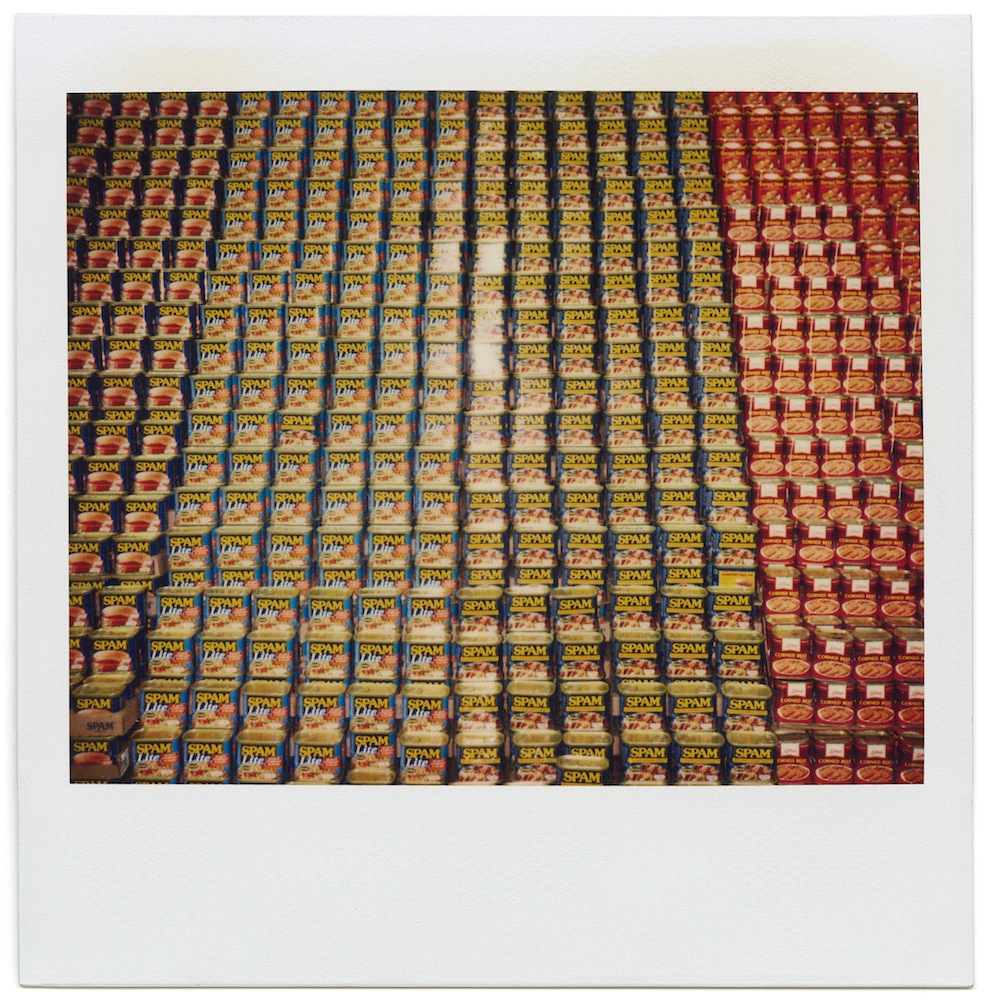

Out now, the clothbound collection of reproduced instant images from the ’90s and ’00s, designed by Interview‘s Editorial Director Fabien Baron, includes a wide range of subjects: Madonna captured behind-the-scenes on set; stacked Spam at an American supermarket; Michael Jordan, a blur on a basketball court; friends and strangers pictured in Cuba, Hungary, Madagascar, and Croatia; teddy bears, street signs, and sunsets. While the Polaroid camera first came to Massee as a tool for work—he likens its former role for set designers to a cinematographer’s light meter—it also became his chronicler: a confidant that quickly captured his surroundings. “These pictures do trigger pretty much the story of my life,” he tells us.

Interview recently spoke to Massee over the phone about how his job has changed over the years and the possibility of picking up the Polaroid camera once more.

HALEY WEISS: Looking through the book, I was struck by the combination of really personal photos with ones of Madonna and Michael Jordan. How did you make the final selection and choose the balance between photos from your personal life and travels versus your work?

HAPPY MASSEE: The way the book started originally, and I mentioned it in the foreword of the book, is that these are all candid pictures that I took that I had no intention of publishing until someone pointed out that some of them were actually quite good. So that’s how the book came about. Before we even designed it and before Fabien [Baron] and I had even discussed it, I had made a photo album that was on my coffee table that included my pictures, and those were my favorite pictures that I wanted to include. It wasn’t Madonna because it was Madonna, it’s because I actually quite like that picture. The same with Michael Jordan—the one where he’s just sitting on his bench press. There were certain pictures that I definitely wanted to include and then others that Fabien took the liberty of pulling from the hundreds of Polaroids that I gave him.

WEISS: You stopped shooting Polaroids 20 years ago, and that was around the time of the computer age beginning. Beyond the advent of new technologies, were there other reasons that you put down the Polaroid camera?

MASSEE: Not really—I guess just the fact that the Polaroid is a little clunky. The one that I was using, the Spectra, is one of the bigger models and it’s a bit of a pain in the neck. Also, film was harder and harder to get. Film was always hard to get when you went to Mexico, Hungary, places like that. Even in the States it just wasn’t that easy to get film anymore because even before the digital era, everybody was turning toward point-and-shoot cameras. I think the one thing that happened between Polaroids and iPhones was the one-hour photo. It was possible for us to still do our job and get pictures in time for our directors using one-hour photos.

Now, because of the advent of the iPhone, it’s so much easier just to take a picture and send it to the director. I think, in a way, the iPhone not only has changed that aspect of my job—I often never meet or see my director until a couple days before the shoot because he physically doesn’t have to be there—there’s [also] so much technology that can just give him all the information he needs before. He personally flies to the location. It’s not just pictures—it’s everything. The iPhone has changed our industry in many, many ways, more than just the obvious, which is to just take a picture and send it via email from your phone.

WEISS: When I was first looking at the images, I think I was expecting more of sets because of your occupation, but there are also intimate portraits. I’m interested in how you think of setting when you’re photographing, and the importance of someone occupying a scene versus just designing the space itself.

MASSEE: All the portraits are really not set up. There’s a portrait of a janitor in Buenos Aires, and she’s this woman that was just sitting by herself in a corner, and she had her orange gloves, and I just asked her to stand up and I shot her against the wall. The same goes for the picture that’s right next to her—I think this Jamaican woman sitting in front of her house. I never set those up. I would walk by them and ask if I could shoot them, and they would say yes or no, most of the time they would say yes. It was never, “Oh, do you mind coming over here because I like this background.” It was always within sitting or standing [distance] in that area where I found them. To get back to the original question—that you were surprised to see that it wasn’t a book about necessarily my work—it’s a book in which every image is connected to a travel related or work related trip. It’s really a photographic diary. Work is great, but out of context there are a few pictures, like the Salvador Dali looking set, [Shepperton Studios, 1994], that was for Guinness. You just show that picture and people say, “Wow, this is weird. What is that?” Then they ask about it or they flip through and get to the picture of the red room, [Red Room, San Francisco, 1997], which is another set that sort of looks like a Stanley Kubrick set. The question that I always get regarding my work is, “Well, what did you do?” And if you’re asking me that question I feel like I did a good job. At the same time it’s very unnerving when people ask me what I do because I have to say, “Well, all the signage is all hand-painted, there wasn’t any furniture,” or, “This building didn’t exist, we added it.” I have to go through step by step and that’s a whole different book in a way. The thing that I really liked about this story that I’m trying to tell in Diary of a Set Designer is my life for fifteen or twenty years: the characters, the celebrities, the people, everything.

WEISS: In the introduction to the book, there’s a portion that reads, “There’s something of the American boy raised on the streets of Paris within these images.” How do you see that in these images?

MASSEE: Malcolm Venville, who wrote the intro, is an amazing writer; that’s why I asked him to write this. I just felt like he added texture to the personality. I always feel like I do have an advantage over other set designers, or I do have a different view of things, based on the fact that I was born and raised in Paris. Even though I was raised by American parents and I used to come to the States all the time, I do have a different sensitivity towards things based on my upbringing. How that is reflected in this book—I was going to say “in my work,” but I’m not a photographer and I don’t aspire to be one… I don’t know that there’ll be a second book, even though a lot of people think that I have another subject that could be really interesting. That’s a whole different story. I did a movie a few years back called The Immigrant with Joaquin Phoenix and Marion Cotillard, and it’s a movie that took place in New York in the 1920s, and it’s all about immigrants coming through Ellis Island and all of that. We recreated and rebuilt New York in that period. Even though I wasn’t born in New York, I think that my upbringing in Europe helped me make that movie in the sense that I was exposed to older civilizations. I wasn’t born in the New World, but I managed to bring the textures and styles to that movie because I was exposed to them, whether we traveled to Italy with my family or England. I saw the old country, and I feel like that probably helped me to a degree when I was asked to make that movie.

WEISS: You also said in the foreword for the book that, “I miss my Polaroid, my constant companion.” I know that you put it down 20 years ago, but have you every felt the desire to pick it up again? Do you think there’s a way in the iPhone world to recover the intimacy of the Polaroid?

MASSEE: It’s interesting that you ask that because I still have the camera; it’s on a shelf in my office. I found a pack of film not long ago and I put it in and it just didn’t work. The camera itself took a serious beating. I almost wanted to include a picture of the camera. … I miss it because I feel like it’s almost too easy to take a picture; you can take a pretty good one with your iPhone. You just enter a couple settings and put a good filter on there and you can turn anything into something that’s kind of magical. I think that that’s the difference between [iPhones] and these Polaroids: You had to capture the magic with what you had. You couldn’t just go in and tweak it. It wasn’t even like a film camera—a film camera you could do that, you could retouch them. A Polaroid is really the only picture where what you got was what you had.

DIARY OF A SET DESIGNER (DAMIANI) IS OUT NOW.