Frank Stella

I wasn’t thinking of becoming an artist. I just wanted to make things and paint for a while. FRANK STELLA

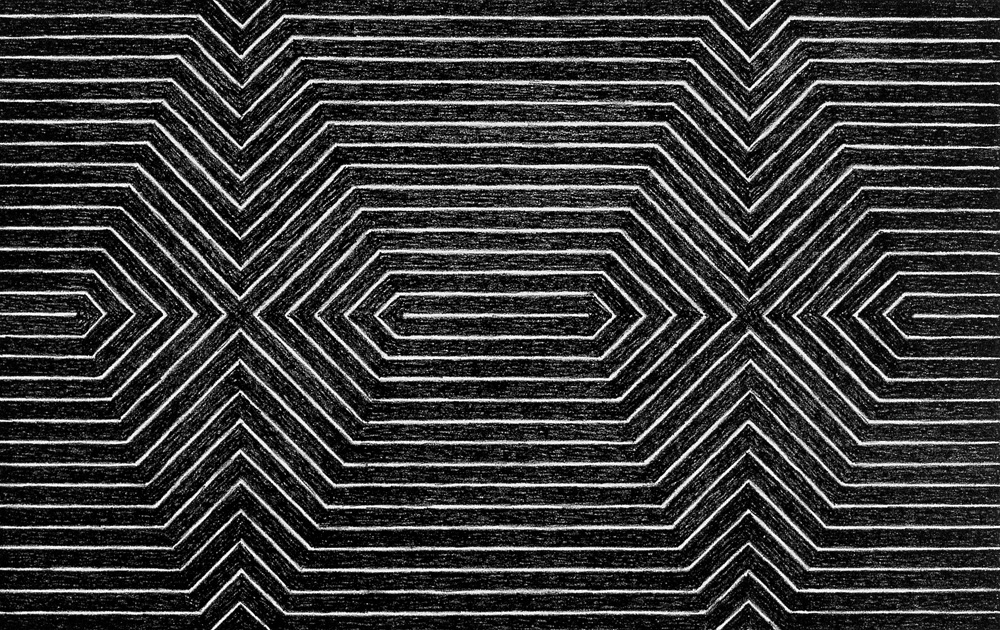

There is no question that Frank Stella is one of the seminal figures of American art. One need only look at his rigorously controlled, almost confrontationally flat, gridded, design-oriented paintings of the late ’50s and ’60s to see how he was reacting against the theatrical, highly psychologized work of abstract expressionists, and how, alongside fellow New York painters Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, he was reinventing abstraction for a new generation. His infamous 1964 quote about his own work—”What you see is what you see”—became something of an instant minimalist maxim. And suddenly, as much as Stella seemed to be resisting certain painterly dramatics, new shapes and possibilities were unleashed. The shaped paintings of Stella’s early career are as coded and straightforward as ancient runes or corporate logos, teetering between the industrial and the painstakingly handmade. They’re like flags of new orders—or new divisions.

But perhaps what truly sets Stella off even from his legendary peers is that the Massachusetts-born artist is no one-time innovator. Almost singularly in the history of contemporary art, Stella has continued to evolve in major ways, never letting his work settle or get stuck in a particular style, decade, or vein. The controlled minimalist of the late ’50s and early ’60s became, in the next decades, a maximalist—the monochrome palette giving way to a riot of color. And it wasn’t long before the two dimensions of the canvas—almost a holy virtue of mid-century painting—made way for a tangle of planes and shapes and spokes that approached and surpassed the precipice of sculpture. Stella has constantly fought the rules and regulations of the painted surface, and even the medium, using house and car paint, cast aluminum, fiberglass, and the latest 3-D-printing techniques. In the last three decades, he’s only increased his experimental approach with sculptural works that near a state of architecture in their vertiginous balance and scale. He’s even allowed narrative—that curse word of formalist abstraction—into his method, particularly in his Moby-Dick series (1985-97), where each piece is inspired by a different chapter from Herman Melville’s distinctly American novel. He’s also used music as an instigator of form with a recent series of works that connect to the sonatas of 18th-century Italian composer Domenico Scarlatti.

Stella moved to New York City in 1958 at age 22 with no definite direction besides wanting to make things. Maybe that vague strategy left him open to change and transformation. It’s hard not to associate Stella with that historic generation of artists drinking at the Cedar Tavern and finding scrap supplies and spaces in which to work in the postwar industrial badlands of mid-century Manhattan. (He shared a studio, for a time, with sculptor Carl Andre and was married for eight years to leading art critic Barbara Rose.) It is also hard not to think of the many artists who have been directly or indirectly influenced by his efforts—a diverse group ranging from master minimalists like Brice Marden to the organic-form color paintings of Judy Chicago all the way to any young artist working today in mixed-media abstraction. Arguably, it is Stella who’s had the biggest lasting imprint on abstraction. At age 78, the artist lives in downtown Manhattan and has a studio in upstate New York. A show of sculptural works produced over the last two decades opens this month at New York’s Marianne Boesky Gallery. In honor of that show—and in preparation for his retrospective opening in fall 2015 at the Whitney Museum of American Art—his friend and admirer, fashion designer Stella McCartney, got on the phone with Stella to discuss how an artist manages to keep making vital work for five decades without repeating himself. —Christopher Bollen

STELLA McCARTNEY: Where are you living these days? Are you up on the Hudson, where your studio is?

FRANK STELLA: No, I’m right in the middle of the Village. I’ve been here since 1968. Such a long time. Before you were even born.

McCARTNEY: But you grew up in Boston.

STELLA: Yeah, in a suburb outside of Boston. My grandparents emigrated from Italy at the beginning of the 20th century.

McCARTNEY: Did you grow up speaking Italian?

STELLA: No, my parents spoke Italian, but I grew up during the war. Italians were very self-conscious during the Second World War. There was a big push for everybody to speak English.

McCARTNEY: Yeah, that’s similar to my family. We came from Russia on my American side, and they were the same way. They left Russia and started a new life. So what were some of your early interactions with art?

STELLA: I went to private school in New England—at Phillips Academy—and they had a prominent, small art gallery. So the art program at my school had a lot of real art in it. They had very good 19th-century American art, like Bacon and Sargent. And their 20th-century art was pretty good, too, with people like Arthur Dove, Hans Hofmann, Josef Albers, and they had a small Pollock. We were really strong on abstraction, actually.

McCARTNEY: And that was a big influence on you?

STELLA: Yes. Really the two biggest teaching influences were Albers and Hans Hofmann.

McCARTNEY: My grandfather [lawyer Lee Eastman] represented Albers.

STELLA: Albers was at Yale for a long time. But most people forget that he actually taught at Black Mountain [College, in North Carolina], so people like John Cage and Rauschenberg knew him from there.

McCARTNEY: That whole period was such an incredible, historic time for American art.

STELLA: Yeah, and Hofmann was a teacher all by himself, in Provincetown and New York City. If you consider the fact that Helen Frankenthaler was Hofmann’s student, her work actually makes a lot more sense.

I thought of it as a kind of structure . . . I can do this and that, and they don’t collapse, so then what can I do from here? FRANK STELLA

McCARTNEY: It’s interesting to think of these great artists as teachers. Did you ever think of teaching?

STELLA: I’ve taught a little, but mostly only for a semester at a time. I don’t think I was a very good teacher.

McCARTNEY: [laughs] That’s not what I’ve heard. So when you finally came to New York in 1958, it was still the height of the abstract expressionists, and they were the ones that really touched your heart.

STELLA: Yeah, that was dominant. Actually, the dominant art of that time was next generation—people like Al Leslie, Mike Goldberg, Helen Frankenthaler, and Ken Noland. There was really a lot going on. It was very, very active. And there was a change in attitude, for some reason. A lot of small galleries began opening downtown and people were taking much more of an interest in young artists.

McCARTNEY: There was a real shift then from the godfathers who were pioneers to the younger generation. I guess it did seem like an entirely distinct generation.

STELLA: There was an interest in their successors—what was going to happen? And they were good at what they did and everybody could sense it.

McCARTNEY: Did you ever travel to the Hamptons in those days and visit Pollock’s or de Kooning’s studios out there?

STELLA: No, we were too young to travel in those social circles. You needed money just to take that trip.

McCARTNEY: You could have taken a train. Or the Jitney, although they probably didn’t have that yet. What did you do to stay financially afloat at that time?

STELLA: I worked as a house painter part time. They had what they used to call the lineup. You just go down to certain places where they need temporary help for painting. You sit there and they call your number and you go out on a job.

McCARTNEY: Isn’t that what a few of the great abstract expressionists did, too?

STELLA: I think most of them were teachers. But de Kooning was a house painter.

McCARTNEY: I’m sure he was a really good house painter. [laughs] A bit messy around the edges. When did you first decide that you were going to be an artist?

STELLA: Well, I liked making things. I decided to come to New York after I got out of Princeton in ’58. I had a little money from my father, $300 or something for graduation. So I was looking for odd jobs and I found a studio where I could work on the side. I wasn’t thinking of becoming an artist. I just wanted to make things and paint for a while. And at that time we had the draft, Selective Service. I was due to go in September or October for my draft exam, so I thought I’d just paint in New York for three months and do what I felt like doing, then go to the draft. I figured I’d be in the Army and then decide when I got out what I wanted to do. I didn’t have any strict plans. I don’t know if what happened was bad luck or good luck.

McCARTNEY: It was good luck for us.

STELLA: [laughs] Yeah, the last doctor stamped me out, said I was undesirable. I had an injury to my left hand, which wasn’t really that serious. But the real reason was that it was between the wars, and they didn’t need anybody, particularly college graduates. There were a lot of kids that needed to go into the Army to have food or a career or whatever. So they got rid of the guys from the top; they skimmed us off.

McCARTNEY: Was your family encouraging of your decision to paint?

STELLA: Not so much. I called my dad up when I failed the physical, and he said, “Too bad. It would have made a man of you.” But he didn’t care too much, as long as I took care of myself.

McCARTNEY: So you settled into life in New York and went out and made friends with other artists.

STELLA: One of the advantages of being young is that you’re quite flexible, you move around. I met people. It was Jasper and Bob who introduced me to Leo Castelli.

McCARTNEY: Wow. I met him when I was really, really young. He was a great friend of my grandfather’s, and I remember him being so classy.

STELLA: He was pretty nice. As much as he had the artists who were very successful, he was very loyal to his artists. Leo agreed to handle me, and I said, “Well, I need a stipend.” I got about $75 a week, which is not a big deal, but if you’re young and an artist, it’s enough to support you and a couple of friends. It worked out.

McCARTNEY: That seems like a big difference from the art world now. What do you think of the art world?

STELLA: Fortunately, I don’t see that much of it. I’m far away from it. But it’s different for everybody, for each generation. They make their own world.

McCARTNEY: But the Castellis of the world don’t exist anymore, do they?

STELLA: I’m sure there are good dealers out there, and there are dealers that the young people are happy with.

McCARTNEY: Yeah. It’s true. It’s a less cynical way of looking at it. Was that such an incredible time for you, that period in New York when you had just started out?

STELLA: It’s hard to deny that. It’s hard to say that my twenties were the most miserable time in my life or that my first wife drove me crazy or that I hated the job that I had. You can say all of those things. But for the most part, people manage to have a good time when they’re that age.

McCARTNEY: You got married rather young and had two children. Did having kids impact your work?

STELLA: You could go anywhere with the kids back then. And people sort of expected it. You’re young, you get married, and you have children—nobody gave it a second thought.

McCARTNEY: What were the pieces you were doing in those years that you had kids?

STELLA: What they called the “banded” or “striped” paintings. They were very rigid works. I did that for about four or five years, and then I was making other kinds of paintings.

McCARTNEY: How do you decide when you’re finished with a certain series and it’s time to move on?

STELLA: You just feel, “That’s as far as I can go with this,” or “What’s the point of this?” As far as I was concerned, with the early paintings, I liked them, I thought they were pretty good, but I didn’t think it was the end of the world. I also thought of it as a kind of structure, a base to build on. So this proves I can do this and that, and they don’t collapse, so then what can I do from here? How can I build on it?

McCARTNEY: Were you afraid? Those works are very identifiable, very iconic. And a lot of artists get trapped there. They can’t move away from it.

STELLA: I guess that happens a little bit. But one of the things was it was very different then, since the amount of money that was involved was so small. There was nothing to hang on to, particularly. So that was one thing. And the other thing is, you think about what you’re doing and what you want to do, but sometimes you’re sort of getting nowhere and you know it. You feel like you’re treading water, right? Feeling like you’re going nowhere is not such a great feeling.

McCARTNEY: But it’s very brave. You must look back and think, “That was quite ballsy.” Because people don’t usually do that.

STELLA: Well, the one thing I learned is not to say anything about my own paintings. Keep my mouth shut. [laughs] You’ll never stop hearing what you said. It will come back to you again and again, people will always tell you about it. Even if you were the source of what’s wrong with it.

McCARTNEY: So financially it wasn’t a risk, but you were getting a lot of acclaim rather young. You were having a lot of shows.

STELLA: Yeah, but Roy [Lichtenstein], Jim Rosenquist, Larry Poons, Claes Oldenburg—everybody was showing everywhere. In the ’60s, it just took off. People started looking at the younger generation and giving them what you might call a pretty big play. It was as though the whole art world just opened up.

McCARTNEY: All of a sudden everyone was an artist.

People started looking at the younger generation and giving them what you might call a pretty big play. It was as though the whole art world just opened up. FRANK STELLA

STELLA: I remember one day I was reading the New York Post. And it had an article saying that the IRS had identified that there were 30,000 artists in New York City. This was in 1959. And I was thinking, “They don’t all fit in the Cedar Tavern, and those are the only ones I know.” [McCartney laughs] But it was true. If they called up the IRS now, I wonder if the answer they’d get would be 300,000. It’s possible.

McCARTNEY: You shared a space with Carl Andre for a while.

STELLA: No. Carl Andre invaded my space. [laughs] He has a wonderful show now on at Dia Foundation. It’s just beautiful. Even I was surprised. I’m really so happy for Carl. It’s easy to put down minimalism, but when you see his show, it really has a lot of resonance. And it’s very straightforward, too. There’s no baloney.

McCARTNEY: Do you still see him often?

STELLA: Once in a while, yeah.

McCARTNEY: So he came into your space and you couldn’t get rid of him.

STELLA: Yeah. He finally got his own studio. A lot of guys then had this reaction to the studio artists, in which they were going to be artists without studios. So Carl would just call up and order his wood pre-cut and have it delivered to the gallery for an exhibition. And then a lot of guys like Walter De Maria were sticking stainless steel poles into the ground in the desert—they didn’t need a studio, so to speak. They did their work in the real world. It was good.

McCARTNEY: And did that slightly lead you into thinking in a more 3-D way? Was any of that connected in how you shifted your own work?

STELLA: Probably, but I don’t know. I think really I just shifted because the dominant idea in painting, at least in the way I understood it in the 20th century, was cubism. And cubism was about being planar, or a description of planes in space. And finally you could see that if you made the planes real, things happened. So it was a way of translating, making a kind of 3-D object that was still quite painterly and didn’t become completely an object. I was just caught in the middle.

McCARTNEY: Yeah. And then you brought that into shaping your canvases, and you injected a lot of color. Those pieces are so sculptural.

STELLA: Yeah, well, they’re more sculptural now than they were then.

McCARTNEY: They are sculptures now! [laughs]

STELLA: But it was the painting part that made them click for me, somehow. To me, the structure was not that special.

McCARTNEY: How did you get into the technical side of constructing those works?

STELLA: It gets interesting. You have the material, which is aluminum. And then I was working in the foundry with Dick Polich [of the Polich Tallix art foundry in Rock Tavern, New York]. I made a lot of casting and open-sand casting with aluminum and then painted it. So that was very exciting and very physical. I made a lot of pretty physical things. But then it started to get too heavy and I wasn’t getting any stronger, so I began to be interested in carbon fiber because it’s light and strong. It’s not so easy to work with unless you have fancy equipment and stuff.

McCARTNEY: And you started working with BMW.

STELLA: Yeah, the automobiles got me interested in carbon fiber and forming the material and everything. And now I’m doing what everybody else is doing, although I was doing it for a while—what they call 3-D printing. It’s rapid prototyping. As you well know, they’re making a lot of dresses and stuff that way.

McCARTNEY: Yeah, absolutely.

STELLA: So that’s an interesting thing because it can be so precise.

McCARTNEY: Does that limit you as an artist? Because the scale of 3-D printing is fairly limiting, no?

STELLA: The scale is limiting, yeah, but you can get around that in ways. I mean, the real thing is you limit yourself because it’s capable of making things so tight and so close, but then you can’t get in there to put the paint on it. You can make very complicated things, but then your own complication gets in your way. Everything gives a little and takes a little away.

McCARTNEY: You mentioned Lichtenstein. Was Warhol also around you at that time?

STELLA: Andy was starting right about the same time I was. I actually knew Andy a little bit. It’s one of those things: he was popular but not all that popular. He was one of the pop artists. And he did some nice things.

McCARTNEY: He sounds so different from you and the other artists you’ve been speaking about. It seems like such a different emotion.

STELLA: Oh, I don’t know. It’s not so different than Bob Rauschenberg. Bob was making those silk-screen paintings, and Andy was using silk screen.

McCARTNEY: I guess it’s less the medium; it’s more the social life around it, perhaps. When you think of Warhol, you also think of the circus that surrounded him. Whereas when I think of you and the artists that you’ve spoken about, you’re much more insular and low-key.

STELLA: But everybody went to the same parties and they all knew each other. I used to be friends with Henry Geldzahler, and Andy was friends with Henry and everyone else. It was pretty much chop suey.

McCARTNEY: It was one of those amazing times in the history of New York and art.

STELLA: Yeah, amazing if you’re looking from the outside.

McCARTNEY: I am looking from the outside. I’m young looking at it and I want to be there now.

STELLA: [laughs] From the inside looking out, you were just caught in the miasma.

McCARTNEY: It’s funny because my mom [Linda McCartney] was in New York during that period, and I know she sort of steered clear of that scene. I don’t think she wanted to get sucked in. I guess that’s one of the reasons she moved to London and got sucked into that scene instead. What changed for you in terms of your work in the ’80s?

STELLA: That was a pretty big change because I changed my way of working, and I was making things that were more complicated. Another thing that happened in the ’80s was that there was a big change in how much you could earn. If you could make $35,000 or $40,000 a year in 1978, that was okay, you could get by. But it tripled by 1980, 1981. The prices just went up.

McCARTNEY: Did that bring a level of competitiveness into the arena? Did you feel any of that?

STELLA: I never noticed competing with other generations. There’s competition within your own generation, but that competition is good. Maybe you’re annoyed that somebody’s getting more money than you are, but what’s really annoying is if someone’s painting a better painting than you’re making. So it’s something to think about and work toward and stay focused on. If the level is high, you get carried along with it. And if the level sinks, it’s pretty hard to keep yourself above water.

McCARTNEY: When you changed from minimalism to maximalism, did that change you emotionally?

STELLA: No, I didn’t notice the difference. I was working. Other people would say things about it, but it’s like saying, “Ah, you’re not doing blue paintings anymore.” So what?

McCARTNEY: I have four kids. And people always made a connection between when I was pregnant and that my runway shows had much more loose-fitting garments. Then when I wasn’t pregnant, the designs would always go back to the body. So I guess it is a natural thing to ask if there is the connection between your emotions and minimalism and maximalism. But at the end of the day, you’re just living it and doing it.

STELLA: Yeah, that’s true. I think for a lot of artists, if you’re lucky enough to have a kind of career, especially toward the end now, you start to think about what the whole ensemble looks like. It’s the whole that counts. The parts are given, but you don’t know how the whole thing’s going to look when it’s all put together.

McCARTNEY: So how is that, for instance, when you look at someone like Philip Johnson’s Glass House, when things are starting to get put together and they’re hung in a certain way? [The Glass House’s collection includes 18 works by Stella from 1960 to 2004.]

You can make very complicated things, but then your own complication gets in your way. Everything gives a little and takes a little away. FRANK STELLA

STELLA: Well, I love Philip, and the Glass House is great. He was a wonderful patron, so I really can do nothing but love him still. A lot of people were testy about him, but he was almost universally good to architecture and artists. I don’t know how anyone could support the visual culture any more than he did.

McCARTNEY: Have you been up there recently?

STELLA: I was last year. It’s still in great shape. And it’s a National Trust [property] now.

McCARTNEY: I want to ask you about your Moby-Dick series. When did you first read that book?

STELLA: I read it twice. It was an accident. It’s hard to find things on the weekend to do with the kids, so we went to the aquarium in Brooklyn, down on Coney Island. This was in the early ’80s. Pretty near the entrance there’s a big tank with beluga whales in it, the white whales. I came in there and they just moved. It was very dramatic. It reminded me of some pieces we’d been working on. We called them wave shapes. And when I looked at the belugas, I started thinking about the waves. I was brought up near the ocean. And I was just standing there thinking about it, and the whales and their forms moving. It was the opposite in every way of a straight line, or a perpendicular plane. It was really about motion and curvature—the curved line rather than the straight line. So I started reading Moby-Dick again, and then I said to one of my older boys that I wanted to work on Moby-Dick. I know a lot of people have illustrated Moby-Dick, but I had a couple of ideas, and I made some pieces that related to it. And I thought, “Well, I’d like to do a piece for each chapter, but it wouldn’t be an illustration. One might be a sculpture, one might be a painting, one a print—different kinds of things.” But I was a little discouraged by the idea, because there were, I don’t know, 200 chapters or something like that. I said, “I don’t think I’m going to come up with 200 ideas that really related to Moby and the waves and traveling and all of that.” And my son said, “Don’t worry, you don’t have to do them all.” And then I got so mad.

McCARTNEY: You got mad at your son?

STELLA: Not mad at him. I was mad at myself. But then I thought, “Screw that, I’m going to do them all.”

McCARTNEY: My God, he gave you a window out!

STELLA: So that’s why there are so many works. I can be as stubborn as Ahab. We worked on and off on them well over 10 years.

McCARTNEY: How do you feel when you look at them?

STELLA: You know, I like almost everything. In fact, I like everything. There are some things that are not that fabulous in a certain way, but I like the variety and the way they move. I think it changed my idea about abstraction or about what I was doing. Abstraction didn’t have to be limited to a kind of rectilinear geometry or even a simple curve geometry. It could have a geometry that had a narrative impact. In other words, you could tell a story with the shapes. It wouldn’t be a literal story, but the shapes and the interaction of the shapes and colors would give you a narrative sense. You could have a sense of an abstract piece flowing along and being part of an action or activity. That sort of turned me on.

McCARTNEY: You talked about cubism having a moment for you. But then you sort of went against it.

STELLA: I don’t know that I went against it. The idea is to go beyond it, right? To continue to see what the trajectory would become.

McCARTNEY: Did any of Picasso’s work ever influence you?

STELLA: Yeah, I think indirectly it’s a huge influence, because Picasso was the one who did basically the same thing. He took cubism as far as it goes into synthetic cubism. All of a sudden his paintings were almost abstract, completely abstract, and then you need to turn back. But what he turned back to were classical figures and the woman. I think there’s a simple reason for that, which is the cubist paintings became flat and planar. And the women have to be modeled. They have to have dimensionality. So a good example for Picasso would be the full-figured woman. He would be more interested in her than he would be in the anorexic model of today. But it’s the fact that women represented volume, or a real expression of volume. And it’s finally a more interesting expression of volume than an actual cube, which would be the cube of cubism. So you have a little bit of volume of the human body versus the volume of a cube. And I think that that made an impression on him.

McCARTNEY: The Moby-Dick pieces are beautiful, Frank. Is it different for you when you approach something that you know is going to be living outside as opposed to indoors?

STELLA: In all honesty, I never worry about it. Sometimes I could see, “Oh, it will survive outside,” and sometimes I thought, “This was going outside but there’s no way it will ever make it.” So I don’t worry about it. I let it do what it wants to do.

McCARTNEY: Do you ever start small and it just grows and grows and grows?

STELLA: Not exactly. I make a lot of very small things, actually. I have lately. And then I make some things that are pretty big. But I don’t make anything that’s gigantic. But the big things are accretions, right? I mean, I have a big piece, and it’s kind of ugly or doesn’t look so good, and then you pile another one on top of it, and then you push it into something, and then it starts to get interesting, or you hide it. You just keep going.

McCARTNEY: And then you’ve got the Whitney coming up.

STELLA: Oh God. Yes, I do.

McCARTNEY: [laughs] I don’t mean to stress you out. How do you feel about retrospectives? Do they freak you out, or do you tend to underplay them?

STELLA: I underplay it. The reality is it’s a wonderful opportunity, and you can’t really be negative about a really good opportunity. What’s the point of that? And the other thing is that I forget that what might be repetitive to me is going to be news to a lot of people who see this show. They’ll have never seen it before. But it’s still hard work. Also any artist can’t get away from the way the world works, which is that it wants to know what you did, and you’re only interested in what you’re doing right now. That’s just a given.

McCARTNEY: You’re the real deal. You’re just in it. Do you remember when we first met? How long did I stalk you for?

STELLA: Not that long. [laughs]

McCARTNEY: I stalked you for longer than you probably know, I’m pretty sure. I definitely was desperate to meet you. And we still have to work on something together. We have to do Stella on Stella, you know that.