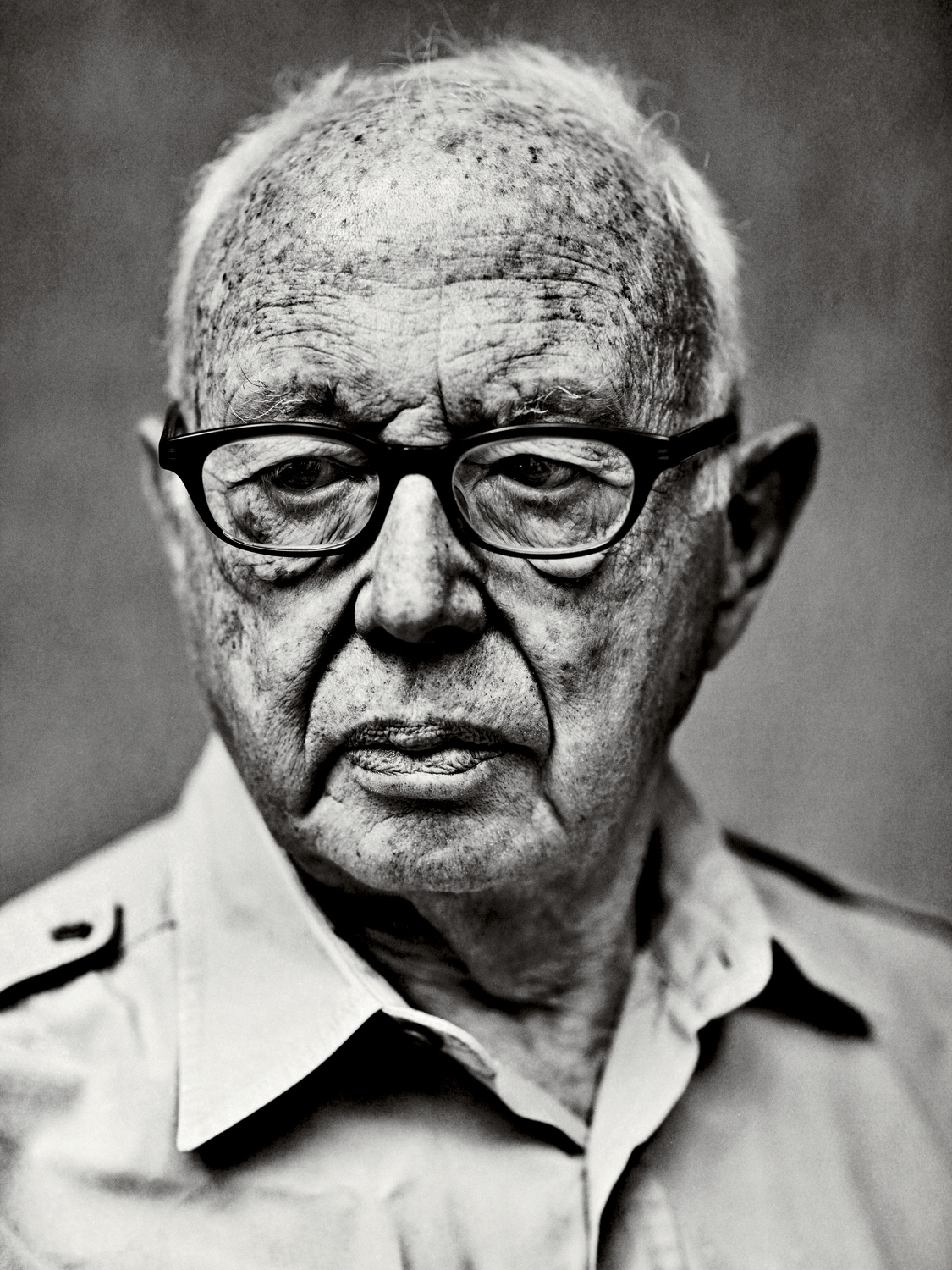

Ellsworth Kelly

This fall, Ellsworth Kelly has two monumental shows in Munich—one museum retrospective of a lifetime of plant drawings, and another a collection of his black-and-white paintings and reliefs—as well as an one exhibition in Boston of his natural wood sculptures. These come on the heels of a number of other shows featuring Kelly in 2011, including a display of recent two-panel relief works at Matthew Marks Gallery this past spring (Kelly is also designing the facade of Matthew Marks’ first Los Angeles gallery space, set to open in January.) That’s a lot on the plate of any artist, let alone an 88-year-old one who has been pioneering abstraction since the 1940s.

Kelly is perhaps the only contemporary artist who has consistently produced great work for seven decades, and not just in one medium or one surface either. He is mostly known for his bold, charged, monochromatic color panels absent of a frame to emphasize their sculptural possibility—works that not only openly fought the popular “dance of dripping” of Abstract Expressionism when Kelly first created them in Paris after World War II, but works that have actually changed our aesthetic understanding of how color and shape penetrate the eye and inform the space around it. His artistic practice has also included figuration in black ink portraits, self-portraits, and nature studies, which he’s sketched ever since he was a teenager; large-scale industrial sculptures that flare out and cleave the air, almost part flower petal, part space ship; and his most recent relief paintings, which stack panels of competing colors over one another to create planes, grounds, and explosive juxtapositions. But in whatever genre Kelly is working, there is an aura of poetry and mystery to his work—something that can’t quite be pinned down, but suggests its foundations in observations of nature, personal relationships, religion, feelings about conflict and geopolitics (Kelly has, in the past, suggested that the Iraq War inspired some of his canvases and even famously proposed his own memorial to 9/11, in which he envisioned a mound of planted green grass at Ground Zero) or just a simple obsession with color waves. He is one of America’s premiere masters of form. He’s also a great storyteller. Having left New York City behind him in 1970 for fear his social life was overwhelming his creative life, Kelly moved three hours north to his current rolling-hilled compound in Spencertown, where he lives and works with his partner, photographer Jack Shear. Architect Richard Gluckman designed his current labyrinthian studio—it serves not only for painting, but as storage space, an office, library, and archive, and will eventually comprise the artist’s foundation. Kelly hurries through the rooms with extraordinary energy, even though he is often on oxygen, with a clear cable trailing behind him. The sky was bright blue on the July afternoon that collector and admirer Gwyneth Paltrow visited Kelly to take a tour of his headquarters and ask him questions about his life in the arts.

ELLSWORTH KELLY: [standing in the exhibition room of his studio] Here are some new works I’ve done. The blue in front is the form and the black is the ground. [Blue Relief With Black, 2011] Except the wall is the ground. So it’s a form on the ground on the wall. This way my paintings become more like objects. People are always trying to do something different, but I feel I’ve been doing this kind of work for quite awhile!

GWYNETH PALTROW: When did you first start making three-dimensional paintings?

KELLY: In Paris in the late ’40s, I started making my first reliefs. They are separate panels. I wanted to do something coming out of the wall, almost like a collage. I did a lot of white reliefs when I started because I liked antique reliefs, really old stuff.

PALTROW: Like what?

KELLY: Roman and Greek reliefs. And then the Romanesque works in the 12th and 13th centuries, where they did a lot of relief sculptures of figures. I had liked Romanesque art from the very beginning of my studies . . . And here is another work [Black White Black, 2010]. It’s three panels, black, white, and black. When you stand in the middle and look straight at the white, something happens to the black in your peripheral vision, something happens to the edge. If you look closely, it’s not a painted edge, it’s a real edge.

PALTROW: It’s very sculptural, almost architectural.

KELLY: That’s what I’ve done in my paintings mostly. I want each color to have its own area of itself.

PALTROW: Why did you start painting on panels in Paris?

KELLY: It meant I could move things easily! [laughs] I started in the South of France, and when I went back to Paris, I put them all in a box, like 64 panels. I don’t remember how I did it, but I got them all in the back of my car with all of my other paintings and went back to Paris with them. [walks into studio, where a number of drawings are propped on the shelf] Here are some works from my own drawing collection. This is a little Matisse from 1913 in Morocco. And here is a Bonnard. And here is Picasso. And this is a little Jasper Johns.

PALTROW: Beautiful.

KELLY: Jasper gave it to me when he came for Thanksgiving. He said, “Here is a little present for you.”

PALTROW: How is he doing?

KELLY: I just saw him the other night over at Aggie [Agnus] Gund’s house. He always has a very interesting shirt on. This one was brown, orange, and black. Almost like a tapis from New Guineau. Oh, I want to show you the façade of Matthew [Marks]’s new gallery that I’m working on. [walks farther into studio] I haven’t shown it to anyone. I haven’t been allowed. [He removes a piece of fabric from a model of the L.A. gallery façade, white with a metal strip across the top of the edifice.] You’re the first person who has seen it. Matthew suggested I do something for the wall. First I thought he wanted something like a medallion. Then I had this idea for this bronze sculpture. I think I may be the first artist who has actually done something like this, changed a building. But that’s still an ornament. I suppose Frank Gehry did something close to it in Venice [California] when he installed the big binoculars by Claes Oldenburg [and Coosje van Bruggen].

This isn’t an ornament. It’s part of the architecture. Renzo Piano told me, “You know, architects now are doing buildings like your paintings.” Do you like it?

PALTROW: I love it. It’s so you. Has Matthew already started building the new gallery?

KELLY: Yes, and he tore down the old building. Not only that, he got rid of the trees in front and the telephone poles. He paid to have the lines run underground. He’s really dedicated to this idea. [moves into another room of the studio] And here is the work for a show I’m doing of my wood pieces in Boston. I don’t put any veneer on the wood because I don’t want to make it into furniture. These are from ’87, I think. This wood is padauk, which is famous for being poisonous. And this is zebrawood.

Who wants heaven? I want another 10 or 15 years of being here. when you get to age 90, you have to accept it. this has bEEN my life. it is what it was. i put everything into it that i could.Ellsworth KellY

PALTROW: Was it the quality of the wood that inspired you?

KELLY: Yes, and I wanted to do as little as possible to the wood. So there’s this wonderful curve. When you’re standing in front of it, the curve is swift, isn’t it? The eye takes it in in a second. But the marks on the wood took a hundred years or more to be made. The marks are a given. The swiftness of the curve versus the marks that took so long to be made—I love it. I will never paint this way. It’s like a chance situation. Anything that grows like this is chance. The markings look like fire sweeping up.

PALTROW: You are making this juxtaposition between the cleanliness of the line and the organic material. What do you think you are communicating?

KELLY: It’s about perception, to feel it somehow. It’s a special way of looking. I have trained my eye over and over ever since I was a kid. I was a bird watcher when I was a little boy. My grandmother gave me a bird book, and I got to like their colors. I said, “Jesus, a little blackbird with red wings.” That was one of the first birds I saw in the pine tree behind my house, and I followed it as he flew into one of the trees—like he was leading me on. In a way, that little bird seems to be responsible for all of my paintings.

PALTROW: One of the things I’ve always loved so much about your art is the ruthless efficiency of your work—your color, your lines. But there is a tenderness to your work at the same time. It’s pristine and efficient and yet deeply emotional. That’s how I see them.

KELLY: I was taught to draw very well when I was in school at Boston. And I grew to enjoy drawing so much that I never stopped. I think all of my work comes out of drawing. [turns to a table in his studio] Here are some studies I’ve done, drawings of rectangles. They are ways for me to see how structures work.

PALTROW: This is how you are able to find out the way in which one shape overlaps another and brings a sense of emotion.

KELLY: Yes. Like layering one hand on another, or anything to do with the body touching. We’re always aware of it. It’s something we as humans do a lot and it ends with kissing and then . . . going to bed. We’re always conscious of the curves, and I want my works to be sexy or voluptuous. People will say, “Oh, well it isn’t so voluptuous. Your work is very simple.” They say, “You are taking too much away.” But I say, “No, I don’t put it in to begin with.”

i was in what they called the camouflage secret army. the people at fort meade got the idea to make rubber dummies of tanks, which we inflated on the spot and waited for germans to see.Ellsworth Kelly

PALTROW: You edit before you begin. I see. Well, I find your work very sexy.

KELLY: Today before you arrived I thought, “What is she going to dress like? How do I see her?” I always foresee people. And I’m glad you wore gray. I was thinking, Oh, she won’t want to wear color.

PALTROW: Gray is my favorite color. And I didn’t want to compete with your work.

KELLY: Gray goes with gold. Gray goes with all colors. I’ve done gray-and-red paintings, and gray and orange go so well together. It takes a long time to make gray because gray has a little bit of color in it. I can’t remember what I mixed in to my gray-and-orange painting. I keep a little source diary on my colors. I get so excited when I finish a painting that I forget about the work of doing it. And I have to wear a mask now when I paint, because my oxygen level is low. My lungs are not so hot. I’m not a smoker. The doctors said, “What the hell is going on?”

PALTROW: Is it from the chemicals from painting?

KELLY: Yes, I think it was 60 years of turpentine [in the paint] that messed up my lungs. But actually now I feel better than ever and I can paint. [returns to table, looking at drawings] Here are some plant drawings. This one is a banana leaf. See the way it overlaps? You don’t have to put shading in. I don’t like shading. Just the line. As I say, the line is the excuse. And it’s fast. It’s always fast. [turns to book of drawings] These are portraits I did in Paris. And this one was done in the war, in 1944. It was done in a tent with a candle.

PALTROW: Did you keep drawing supplies in your army bag with you?

KELLY: I bought them where I could. And I did a painting like this one, holding a bugle. I actually showed a photograph of that painting [Self Portrait with Bugle, 1947] to [Fernand] Léger when I went back to Paris after the war because he had a school there. When he saw the photograph, he said in front of his class “This guy should go back to America and blow his bugle.” [laughs] I left. I never went to him again. [opens another book of drawings] Here are self-portraits. I was visiting a sculptor in Spain, and his bathroom was all mirrored. So I went in to take a shower and shave and I said, “Oh my god, I have to draw this.” [turns page] And I drew this portrait of me at the Mayo Clinic, getting a heart treatment [Self Portrait at the Mayo Clinic, 1987]. I was very worried because they said there was a percentage of people who didn’t make it through the operation. I was so upset. But what I did was take this little piece of paper that was in my wallet and drew this self-portrait and then I felt better.

PALTROW: I wanted to ask you about your time serving in the army. You went overseas for World War II. Did you volunteer?

KELLY: I went to Pratt [Institute] right after high school. I was there for a year, and I read an article in the paper about the Army working with camouflage in Fort Meade, Maryland. I didn’t want to be in the infantry, so I wrote them saying, “I’m an artist and I’d love to be in your outfit.” They said, “Get in the Army. We have your name. We’ll find you.” And that’s what they did. Life had been peaceful up until high school, but the business of the Nazis and Pearl Harbor was very strong, and I guess I wanted to insist that I could live a man’s life.

PALTROW: Did you design camouflage while in the army?

KELLY: I did posters. I was in what they called the camouflage secret army. This was in 1943. The people at Fort Meade got the idea to make rubber dummies of tanks, which we inflated on the spot and waited for Germans to see through their night photography or spies. We were in Normandy, for example, pretending to be a big, strong armored division which, in fact, was still in England. That way, even though the tanks were only inflated, the Germans would think there were a lot of them there, a lot of guns, a whole big infantry. We just blew them up and put them in a field. Then all of the German forces would move toward us, and we’d get the call to get out quick. So we had to whsssh [sound of deflating] package them up and get out of there in 20 minutes. Then our real forces, which were waiting, would attack from the rear.

PALTROW: So in a way, it was just like an art installation! That’s amazing.

KELLY: One time, we didn’t get the call and our troops went right by us and met the Germans head on. Then they retreated, and they saw our blow-up tanks and thought they were real and said, “Why didn’t you join us?” So, you see, we really did make-believe.

PALTROW: It’s the perfect job for an artist in combat.

KELLY: We even had the tank sounds magnified because tanks would go all night long.

PALTROW: You must have loved France, to stay there like you did and study after the war.

KELLY: I loved Paris. My best friend in the army, Griswold, from an old Lyme, Connecticut, family, he met Picasso. This guy looked like one of Picasso’s blue period models. In fact, there are a couple of drawings that Picasso did of Griswold. You see, we were stationed about 10 miles outside of Paris for a while. There was one train that took us in at four in the afternoon, and then we would have to walk back. We’d get back at five in the morning and have to go directly to work. But it was wonderful. Anyway, I went back to Boston after that and stayed for a while. I remember I went into the bar downstairs from where I was living. This was in 1946 or 1947. It’s the bar where I’d have a beer with friends, and I saw this little box moving like a movie. I said, “Oh my god, what’s that?” The guy said, “It’s a television.” I said, “I’d better go back to Paris.”

PALTROW: So the invention of television made you return!

KELLY: Yes. But for an artist going to Paris was an old tradition by that point. I was so poor, and France was cheap, and I had a G.I. Bill. I didn’t come back from Europe until I was 30, and by then I already figured out my style of painting. In France, they thought I was too American. And when I came back, people said, “You’re too French.” I just stuck to my guns and continued painting. I thought I had something really important that came to me in France. That was hard, though, because it was right at the moment of the breakthrough of the Abstract Expressionists.

PALTROW: I know you shared a studio with Agnes Martin for a while. Will you tell me a little bit about your friendship with her?

KELLY: We lived in the same building, two buildings right next to each other that had the same stairway. I was on the right, she was on the left. It was down by the Staten Island Ferry dock on Coenties Slip. She had a higher ceiling than my studio because she was on lower floor, so sometimes I’d say, “I have a painting I want to do that’s bigger than my room. Do you mind if I do it in yours and you can take off for a while?” We became friends almost immediately when we met. I remember I’d sit on the couch in her place, and in front of the couch was a wood plank, and Agnes would pick it up and you’d look down and see water.

PALTROW: Really?

KELLY: Yes, because we were on the East River, literally. We were one block away from it.

PALTROW: You and Agnes were really close?

KELLY: She was like an older sister, a buddy. When I was finally able to buy a car, a Volkswagen, we used to drive to the beach a lot together. We talked about poetry and reading and all of that. There were lots of artists down near Coenties Slip—Bob Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly, who used Rauschenberg’s studio when he got started. This was in the ’50s. Rauschenberg was something of a mentor to him.

PALTROW: I would have thought it might have been the other way around.

KELLY: No, Bob had a great influence on Cy. I eventually moved away from Coenties Slip up to Hotel des Artistes on 67th Street. I was on the ninth floor, the top floor. The elevator wasn’t big enough, and I’d have to stand on the top of the elevator and get my paintings down that way. Finally, I thought, I’m not going to paint any more pictures here. It was just too much. And they were turning it all into a cooperative and wanted me to buy it.

PALTROW: Is that when you moved up here to the country?

KELLY: Yes, in 1970. And another reason I moved was that I was doing too much social stuff in New York. I wasn’t painting anymore. Also in ’69, Bill Rubin at the Modern [MoMA] had offered me a show and I thought, “Geez. I’d better get busy.” I started doing sculptures up here. But when you go away, you miss New York. When I go down now, I feel the energy again. But it’s like Bob [Rauschenberg] went to Captiva [Island], and Jasper Johns moved up near here a couple of years ago. He used to have a place in South Carolina. And Roy Lichtenstein was out in Long Island. You’re out in Long Island now, in the Hamptons, but just for the summer, right?

PALTROW: Yes. I’m in London for most of the year. I married a British musician, so I live there for the most part now.

KELLY: I don’t watch very much television, but Jack and I saw you on Glee. You were so good in that.

PALTROW: Oh . . . ? Thank you!

KELLY: You really looked like a teacher to those kids. You sang and danced like crazy, and you looked like you were having a lot of fun.

PALTROW: I had a great time. And I love picturing you two watching Glee.

KELLY: You also did a movie where you sang.

PALTROW: That’s right. My father always used to tease me and say, “You can imitate everyone else’s singing, but you don’t know what you really sing like.” This past year, I feel like I finally found my voice in a way—my own voice—just because I was doing so much singing, doing so many different styles, performing in public. It’s a position I really didn’t expect to be in. It’s very vulnerable.

KELLY: It’s like what Jasper is famous for saying. How do you explain your paintings? He said, “Well, you do one thing and then you add something else to it.”

PALTROW: Yes, you just let the truth emerge.

KELLY: With painting, it’s all in the eye. My eye is very impersonal. It can say what is good and what is bad right away.

PALTROW: I have always seen a lot of horizons in what you do. I wondered about that in connection to Agnes Martin.

KELLY: She’s wide open. She painted the desert. She loved the desert.

PALTROW: When she moved to New Mexico, she brought her works down in size, five-feet-by-five-feet from six-by-six. But it’s funny, she shares with you that sense of efficiency. But your work is more emotional, where hers is more spiritual. But it’s interesting how much can be expressed in a single line.

KELLY: I came up against that a lot with people who don’t think my content is visible. Or find it lacking. I always say, “It’s not a Marilyn Monroe.”

PALTROW: I think, for me . . . Obviously, everyone has different tastes, but I find your art the least kind of narcissistic because you’re presenting something that a person is able to feel. I get why Andy Warhol was a genius, but for me, it’s a bit too self-aware. It’s too all about him.

KELLY: Well, that’s why he’s so famous, I think. A lot of young painters even now love to incorporate celebrity. One idea of being a painter is to use what’s happening at the time. Velázquez was painting of his time. And so was Rembrandt. And Francis Bacon was painting his time in London. He was a real mover, but he saw the insect in the rose. But yes, when I do a painting, I want to take the “I did this” out of it. That’s why I started using chance, like the markings on the wood. I never wanted to compose. I didn’t want to say, “I do curves this way, and make this a square, and that a rectangle.” I remember when I was a little kid, the teacher gave us a piece of construction paper. It had bumps in it. She said, “Today we’re going to do a drawing of springtime. Choose a drawing that you want to do of springtime.” I decided to do a flower, a purple iris with green leaves. I drew it very quickly in a pale outline, and I noticed when you put your crayon on this paper, it only hit the top. It didn’t go all the way down—or through. So I pressed down in order to get rid of the bumps in the paper. When I pressed down I realized I could get a really solid color. I couldn’t stay within my lines. I thought, I’m just going to cut this out and glue it on another piece of paper, and I’ll do the stem and leaves the same way. Then when my teacher came over she said, “Kelly, we’re not here to make a mess. Go stand in the corner.” You know, here was my first collage. But all kids probably do this, don’t they?

in france, they thought i was too american. and when i came back, people said, ‘you’re too french.’ i just stuck to my guns and continued painting.Ellsworth Kelly

PALTROW: Absolutely. Mine do.

KELLY: This was my first collage, building up blocks of solid color. And everyone else was drawing so palely. So I get up and I nervously got in the corner and said, “Jesus, adults just don’t get it.”

PALTROW: Weren’t you right . . .

KELLY: I had that feeling with my parents, too. Especially about religion.

PALTROW: Are you very religious?

KELLY: I’m not even a doubter. I’m an atheist.

PALTROW: Do you believe in anything?

KELLY: Nature. What this is.

PALTROW: You’re a pantheist then.

KELLY: Yes. I want to paint in a way that trees grow, leaves come out—how things happen.

PALTROW: It’s funny because I’ve always felt there was so much god in your work.

KELLY: I feel this earth is enough. It’s so fantastic. Look up at the sun. It’s millions of years old and still to be millions more. And there are all the spaces we can never see. But my parents sent me to Sunday school. I didn’t like it. I didn’t like the whole ceremony of church. One night, I remember I had to sleep in my parents’ bedroom. I can’t remember why. They had three boys, and I was the middle one, so maybe there wasn’t room. Anyway, that night I wasn’t asleep yet and I heard my mother say to my dad, “Ellsworth asked me a question today that I couldn’t answer. He asked me, ‘If heaven is so great, why don’t we just kill ourselves?’ ” Of course, you’ve heard this kind of story. Kids think these things. She told him that she couldn’t answer my question. At that moment I thought, “They don’t know. They don’t know it all.” I think that’s the moment that I became an atheist. Who wants heaven? I want another 10 or 15 years of being here. When you get to age 90, you have to accept it. This has been my life. It is what it was. I put everything into it that I could . . . Does it alarm you that I’m an atheist?

PALTROW: No, not at all.

KELLY: I think America should get rid of this fundamentalism in order to think straight.

PALTROW: My feeling is, if you’re talking about something you believe, you can say, “This is what I feel” or “This is what it’s like for me.” But if you have any self-awareness, you can’t say what you believe to be true is true. And in that respect, religion causes a lot of the problems in the world. I personally believe in some sort of divine order—or energy. I do believe that everything happens for a reason. I do think that when something bad happens to someone it’s with the purpose of awakening them. I do think there is some force behind that. I don’t think there are accidents. But it’s interesting to have small children like I do who are starting to ask these kinds of questions.

KELLY: What do you tell them?

PALTROW: One thing I love so much is getting out of their way. I’m so aware of how powerful a parent’s words are. I try to encourage them to think for themselves, and they are completely without prejudice. It’s the most incredible thing. There is no difference between black people and white people. They see [Paltrow’s friends] Michael and Thomas as a couple the same way they see their father and I as a couple. They have absolutely no sense of what is considered “normal.” They’re open and receptive.

KELLY: But there are outside influences coming in, aren’t there? On television. I feel TV is only built on money, on advertising, what they are selling.

PALTROW: A lot of it is.

KELLY: I guess some of it isn’t. PBS is good to watch. For example, I’m so interested now in what is going on with the Republicans. And I watch Rachel Maddow, who is really young and tough. She gets you worked up by telling you things that you didn’t know about, and then says, “I’ll be back in one minute.” Suddenly you’re watching a bunch of stuff you don’t want to look at. You don’t want to think about buying a car or about shaving cream. [Paltrow laughs] I mean, this is them trying to grab your brain, to sell you something, to hypnotize you with advertising. But, really, I just can’t understand these politicians, especially Republicans. They want to not have Obama get anything done. I think it has something to do with race.

PALTROW: They were like that with Clinton as well.

KELLY: Yes, but now even Democrats are saying that he isn’t strong enough. That he is acting like a Republican and they voted for a Democrat. He’s strong enough for me. I can read an honest person and someone who really wants the best thing to get done. I look at Boehner and I say, “He’s not straight.”

PALTROW: Did you ever have a mentor or someone to guide you?

KELLY: I think those six years in Paris I had of freedom is really what allowed me to keep my original ideas. But before Paris, I did meet a woman who was a faith healer. I had a stammer as a child and she sort of took it out of me. My time in the Army was difficult because of my stammer—I sometimes felt inadequate. So I’d come down from Boston to see her in New York. She stayed in that all women’s hotel, the Barbizon. She taught me to relax and self-hypnotize. I eventually had this catharsis, all this built-up emotion that I finally let out. But I continued to play with self-hypnosis after that. I could tune sounds in and out and control my blood flow. I probably entered some dangerous worlds. I tried to go back to this woman six months later for a “rejuvenation,” but she had found religion. She was magic, though.

PALTROW: Have you ever taught art to a student or been a mentor to a younger painter?

KELLY: I knew a young painter who liked my work and wanted me to be his teacher. I said, “I can show you the way to do certain things that I know, but I don’t want to be a teacher.” Andy Warhol was a teacher without trying. He got a lot of young people interested in his way of life.

PALTROW: Sort of Svengali-ish.

KELLY: For me, I just want to make works that mean something. And I don’t know where it comes from or what it means all the time. How can you know what abstraction means? So much abstraction that I see doesn’t have any meaning. It looks like design, a set-up. I want something that continues over time.

PALTROW: But it isn’t your job really to create theories for your work. It’s the artist job to create from the purest point what they’re doing. It’s our job as an audience to go in and try to understand it or not understand it. I think I was about 16 years old when I fell in love with your drawings.

KELLY: Sixteen?

PALTROW: I went to school with Anne Bass’s daughter. I was in her apartment, and she has a lot of your drawings. Her daughter was one of my best friends in high school. They had a dining room full of Monets and a giant Picasso. But I was obsessed with your drawings. They made me understand something about myself as a teenager and put me on a whole other road.

KELLY: You have to be open to it, I guess. I believe people have to be open to what’s happening when they’re alive.

PALTROW: I’m proud to say I have a couple of your plant drawings. I love them.

KELLY: Some fellow recently had taken one of my plant drawings with a whole bunch of leaves and made a tattoo out of it. He came to me and said, “Here.” I said, “It’s great, but you did it without me, so I can’t number it among my paintings.” But do you know Carter Foster? He’s the curator of drawings at the Whitney. I created a tattoo for him, four panels—red, blue, black, green—going up his arm. At the dinner at Indochine after my last opening at Matthew Marks Gallery, I asked Carter to stand up and roll up his sleeve to show his new tattoo to everyone. I made him get in the light so they could really see it. It’s even got a number, so it’s just like a painting.

Gwyneth Paltrow is an Academy Award-winning actress.