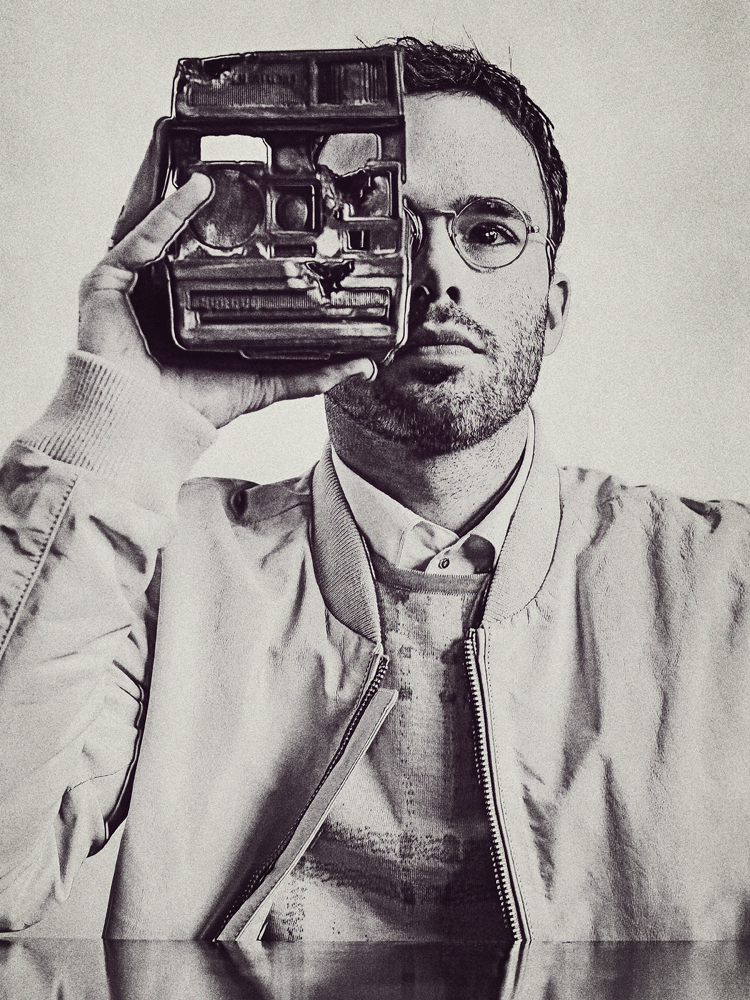

Daniel ARSHAM

Daniel Arsham was raised in Miami, but on a post-blizzard visit to his Greenpoint studio last February, his artwork resonated with the piles of New York snow. The 33-year-old artist’s latest works are stark sculptural castings of what he describes as everyday, Americana objects: a ball rack of basketballs made out of glinting crystal, a McDonald’s sign cast in obsidian, and a pyramid of baseballs, each ball formed from a different material (volcanic ash, steel, and glacial rock dust, all of which he orders on eBay). For Arsham, these sculptures are “future artifacts,” and like the melting snow, they appear to be in a state of erosion, with wound-like craters disrupting their pristine facades. “It’s not a trick,” Arsham says. “Let’s say a camera gets calcified over a thousand years in crystal. It would look just like the one I made, and the materiality will be the same.”

The sculptures also serve as the subject for Arsham’s large-scale paintings, which are fastidious, black-and-white renderings that recall Robert Longo’s bold charcoal drawings of the natural world. Most of Arsham’s time is spent painting, and he exclusively uses gouache as a nod to architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright, who used it to make architectural drawings. Arsham’s work has largely been colorless—partly, because he is color blind. But unlike, say, New York artist Terence Koh, whose use of whiteness borders on fetishistic, Arsham’s work feels clinical—”neutral,” he says—and often dissolves seamlessly into gallery walls. “Walls are white because chalk was white, and chalk was thought to be clean,” Arsham posits. “Modern walls are white because of sterilization.”

While a show this month at Los Angeles’s OHWOW gallery is a one-man exhibition of these archeological sculptures and paintings, Arsham’s superclean aesthetic has, in the past, translated into almost every medium and mode of collaboration, including stage sets for Merce Cunningham, a film project scored by Swizz Beatz, a book for Louis Vuitton, a series of keyboard sculptures with Pharrell, and Snarkitecture, an architecture-design practice he co-runs out of his studio. While working, Arsham and his four assistants wear white laboratory coats, each embroidered with invented titles like “Archaeological Crew Chief” and “Field Crew.” “It’s helpful to make work from a particular vantage point,” he says. “Clothing makes you feel different, and when I put this on, I feel differently than when I walk around in the street. In the studio, I can be whatever I say I am, and this is what I am right now.”