Carolee Schneemann’s Art is Not Made for Your Comfort

In Meat Joy, a performance that Carolee Schneemann debuted at the Festival of Free Expression in Paris in 1964, the artist and several of her friends writhed on the floor while rubbing raw fish, chicken, and sausages across their half-naked bodies. This gutsy, groundbreaking work, along with countless others that followed in Schneemann’s six-decade career, has had a clear influence on a new generation of female artists. (Take, for instance, Lady Gaga, who acknowledged the performance by appearing at the 2010 MTV Video Music Awards in a dress made of flank steak.) Whether she’s working in painting, experimental film, or performance—or a combination of all three—Schneemann uses her own body as the primary medium to explore the politics of gender and representation. As part of another pivotal piece, Up to and Including Her Limits (1973–76), Schneemann dangled in a harness, scribbling and drawing on the paper-covered walls and floor as her body swung every which way—a response to the puffed-up, male-dominated era of abstract expressionism. A decade later, Matthew Barney began his early Drawing Restraint actions, in which he attempted a similar feat while tethered by bungee cords.

Despite Schneemann’s far-reaching impact, she has been largely overlooked by the art world—until now. Late in 2015, the Pennsylvania native mounted her first comprehensive retrospective at the Museum der Moderne Salzburg in Austria; this past spring, she was awarded a Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale; and this month, her retrospective—which includes paintings from the 1950s through to her more recent assemblages, installations, films, poems, and performances—will travel to New York’s MoMA PS1. At 78, Schneemann is still producing new work, most recently a project about the Syrian refugee crisis. [Editor’s Note: Schneemann died today at the age of 79. Her gallery confirmed her death to Artnet this morning.] The artist spoke with Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist about her roller-coaster legacy and the similarities between farm work and art.

———

PIPILOTTI RIST: Congratulations on your Lion prize. It’s very well deserved. How did it feel to win?

CAROLEE SCHNEEMANN: It’s made me very depressed and confused. I’m used to working with neglect and misunderstanding, so this has been really challenging. It’s a different psychic realm. The Lion did not land easily here.

RIST: It drowned in the ocean between Venice and New York? [Schneemann laughs] I want to tell you that you were and are a hero to me. You’ve been a very strong influence for many.

SCHNEEMANN: There are a lot of things that link our work having to do with assessing your environment, and then aggressing it. There’s an aspect of our work that becomes physical.

RIST: When we work in the protected circles of art institutions or galleries, among people who have similar mind-sets, do you think it’s important to jump outside of them? For example, are you known in rural Pennsylvania, where you grew up?

SCHNEEMANN: No. If I’m known there, it’s in a prurient way. Everything gets sexualized. Where I grew up, the only artist people respected was Norman Rockwell. If you thought you were an artist, then why couldn’t you paint like Norman Rockwell? The people from where I grew up have no appreciation for Paleolithic rocks or menstrual calendars. I’m a retriever of lost iconographies. But I had real training and have deep discipline, and I believe in it. Too much of the work I see today is just cultural junk. It’s very superficial and has no rigor. It doesn’t address the dynamic and real politics of an aesthetic structure. But what about you? Is there any audience in the village or city where you grew up?

RIST: I would say it’s similar. But it does interest me to jump out of those comfortable circles and have discussions with those at a distance.

SCHNEEMANN: I grew up doing farm work, and there’s a deep connection between the demands of farming and the demands of art creation. My sense of space and material has a lot to do with having been a chicken-killer and working with cows.

RIST: Could we restage your PS1 retrospective in your hometown?

SCHNEEMANN: No, because they’d trash my house. They’d burn down my barn. They’d chop down my trees. They might even think they should rape me. My work is all about forbidden aspects of the female experience. If I have a piece that says “blood” or “vagina” or “intercourse” or “sex,” that would have no deeper meaning to them than to be provocative. And it’s very dangerous for a woman living alone in the countryside.

RIST: Do you think that attitude might change in subsequent generations?

SCHNEEMANN: I think it’s about context and environment. Especially now, my country is completely chewed up and divided. There was a sort of redneck bar down at the end of my village where the working people went to drink. Then it got bought by an old guy who makes collage. He would come down at midnight with scissors and paper and glitter and glue, and turn the whole place into this big, wonderful collage. So the people in the village do have some experience with art and imagery.

RIST: He opened their world.

SCHNEEMANN: Yes, exactly. And they love it.

RIST: In the end, it’s always a single person who makes change. But I do think we should try to send artists out into the world and not have them all stick together in the big cities.

SCHNEEMANN: I’m of the opinion that we don’t necessarily need so many artists. I recommend that many of the people who think they want to be artists should go into the [American] Friends Service Committee, or do government outreach to communities that don’t have water, or that need seeds or ecological assistance. It would create a system in which people with engaged sensibilities and potential insight assist instead of imposing. I think it could leap right out of the art world into wonderful community action, just like the kind that happens in cities where small groups begin to revitalize a space with action, with information, with graffiti. Is that happening where you are?

RIST: On a small scale. Artists are moving to rural areas because there isn’t the same necessity to be in the city. But in Europe we also have the tendency to rot together in the big cities.

SCHNEEMANN: We have some very powerful examples here in the United States, like in Detroit, where there’s been an intensive grassroots movement by local communities—black and white—to bring life back to the city. They’ve opened restaurants and built gardens and started independent schools. They have lots of abandoned buildings that they turn into galleries. It’s really happening and taking on a cultural and social identity that’s viable and powerful. And the artists are central to it.

RIST: That sounds to me like utopian thinking.

SCHNEEMANN: But how do we get utopian thinking in a dystopian world? These days we aren’t talking to each other—we’re screaming and trying to hit each other over the head with rocks and sticks. A primitive fury has been unleashed by a president who has no culture, who cannot read, and who wants to determine power and aggression.

RIST: I’m very sorry.

SCHNEEMANN: [laughs] Thank you. It’s a very sorry thing.

RIST: That is an annoying side of democracy. The pendulum falls often in the extreme, and then we have to bring it back. It’s never stable; it’s a permanent discussion about finding a way back.

SCHNEEMANN: But it’s really hard to have a fair discussion when you’re faced with militarism, aggression, and greed. The militarists do not want dialogue. They want what they want. They’re psychotic. They’re greedy, they’re narcissistic, and they’re dangerous. You can’t restore the ocean when you’ve polluted it beyond its absorption of toxicity. All I can say is that the sky is still here. I’m lucky to live in paradise. I live in a magical place.

RIST: You live in the countryside in upstate New York?

SCHNEEMANN: Yes. I’ve lived in this old farmhouse for more than 50 years. Meat Joy was dreamt here. Fuses [Schneemann’s 1964–67 self-shot 16mm film, which features Schneemann and James Tenney] was filmed here. Water Light/Water Needle [an “aerial kinetic theater” performance from 1966] was first done in the trees here. Jim Tenney [the late composer and Schneemann’s former husband] and I were students sort of squatting in a house that belonged to a cousin of mine, and it’s a very sacred house. It was built in 1750 out of stone. I’m sitting in it right now.

RIST: There’s a certain kind of energy in the countryside that I can feel.

SCHNEEMANN: Did you grow up in the countryside?

RIST: Yes. My grandparents were farmers and my father was a physician, a country doctor.

SCHNEEMANN: That’s what my father was, too!

RIST: What did your mother do?

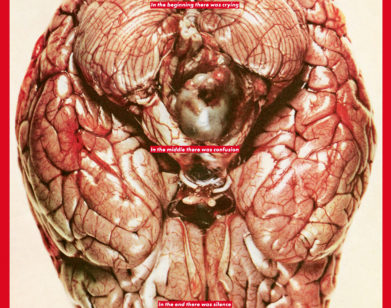

SCHNEEMANN: She was a mother. She had to answer the phone and help people who were hurt. She had children and gardens and trees and the community. She was always overwhelmed. My father was a very inspiring figure. I remember looking at all of his anatomy books. He was happy that I would prowl around and look at things that I wasn’t supposed to see.

RIST: Did you ever go on calls with your father?

SCHNEEMANN: I liked to go in the car with him, and I’d wait while he delivered a baby. I learned to be patient. I didn’t want to be home helping my mom; I wanted to get out of the house. And because his office was in the front of our house, people who got injured would come to the door. I was trained that if they were injured to get a chair for them to sit down or give them a towel to cover the bleeding. My father was really funny—he’d come home from the office at lunchtime with two green bottles. One was ginger ale and one was a urine sample. [Rist laughs] We had to guess which was the one we’d drink.

RIST: Were your parents supportive when you said you wanted to become an artist?

SCHNEEMANN: No. And it all went wrong. My father wouldn’t send me to college. I was so lucky that Bard gave me a scholarship. It was a miracle.

RIST: It shows that you were a strong teenager.

SCHNEEMANN: I had to be. It was before the era of women’s self-determination had taken off. My teachers always said, “You’re very talented, but don’t set your heart on art. You’re only a girl.” I was inspired by Virginia Woolf in 1960, but they wouldn’t let me write about her. They said she was a trivializer. I also wanted to do a paper on Simone de Beauvoir, and my philosophy teacher said, “Why would you write about the mistress? Write about the master.” That was Sartre.

RIST: That’s almost unimaginable to me. It sounds like a bad movie.

SCHNEEMANN: It was a bad movie.

RIST: I read a quote of yours from 1993 where you said, “I’m a painter. I’m still a painter and I will die a painter. Everything that I have developed has to do with extending visual principles off the canvas.” Is that still your position now?

SCHNEEMANN: Yes, it’s the same. I’m now working with computer systems and elaborate projections, and I’m working with the imagery of dead bodies from Syria. But the way I understand composition and form and my ability to enter into material all comes from my disciplines and my commitment as a painter—my energy, my arm, my eyes, my sense of space and form and time. It’s a wonderful realm for me. I never leave it. What about you? Was painting in your background?

RIST: I actually had a quite different approach. I did not go to art school thinking that I was an artist; I went there mainly doing stage sets for bands. I considered my work more as an applied art for musicians, not as art in and for itself.

SCHNEEMANN: That’s why your work has so much to do with environment and sound and energy.

RIST: You’ve also worked in different media. You’ve collaborated with musicians, poets, choreographers, and filmmakers.

SCHNEEMANN: I didn’t want to do that but the energy was irresistible; each stroke of paint was an event and it demanded that the body should respond.

RIST: Like your famous work Up to and Including Her Limits.

SCHNEEMANN: And there was Eye Body [36 Transformative Actions for Camera, 1963], where I thought I could combine my body with painting constructions; I thought my body could become part of the collage. I didn’t understand that after I made that photo sequence, the culture would just look at the body. It wouldn’t understand the integration. It took a long time to have the context change to support what I thought I was doing.

RIST: In those works, you were speaking not only about the female body, but about the human body. There are so many more layers than what people gave you credit for.

SCHNEEMANN: Exactly. It took many years, but feminist analysis, feminist principles, and the social dynamics of women redefining their lived experience has all come together to support my motives. It’s been very gratifying. It was very painful when the cultural historians who were feminists took my work to be playing into male hands because of the use of the body.

RIST: I’ve had similar experiences with things being misinterpreted. It will probably take several more generations before the female body can be considered a stand-in for the human body.

SCHNEEMANN: We might not have that chance, Pipi. With this fascist swell of political deformations, we might be going backwards. But you have a great international appreciation now. Are you aware of that?

RIST: It’s impossible for artists to accept compliments.

SCHNEEMANN: [laughs] Okay. Do you have pets?

RIST: I have no animals, unless you count my two kilos of bacteria. I’ve learned that the average human body has two kilos of bacteria living in and on us.

SCHNEEMANN: Are you doing something with your bacteria? Or is it just doing what it does?

RIST: That’s personal. So, how did this PS1 retrospective come together? It was first in Salzburg.

SCHNEEMANN: The story begins with the wonderful critic Kristine Stiles, who risked her standing as an art historian in the ’90s trying to promote my work. With a few exceptions, it was always shut down and she was always disappointed. But then this European curator Sabine Breitwieser came along with such brilliant commitment and made this exhibition possible. It’s so wonderful to me because all of this work was rejected for so many years. I still find it confusing.

RIST: You mentioned you are also working on some new pieces that involve Syrian corpses.

SCHNEEMANN: Yes, corpses of hundreds of men, tortured, starved, thrown around. I’ve been concentrating on that work. And I have a lot of smaller projects as well. It takes so much time because I have a lot of health issues. It’s a very difficult age when the forces of time want to destroy us and take us away. They’re just snatching people like devils; death comes and grabs each of us.

RIST: It has no mercy.

SCHNEEMANN: There’s no negotiation.

RIST: How do you relax? That’s something I find particularly difficult as an artist.

SCHNEEMANN: I don’t even like the word! If I have a partner and we make love a lot, then I’m in a very pure state of being. But here on my own, I relax by watching my cats. I have an amazing cat now; she’s absolutely brilliant and thrilling and thoughtful. And she has all kind of tricks. One is that she goes in a lilac bush when I’m on the porch, and she makes it shake. So you’re quietly sitting there, and all of a sudden this little tree is shaking all over. That’s the cat’s trick to amuse us. I also love watching birds. I was in the hospital a lot last year, and I had to learn to walk again. I learned through that experience that I could sit in bed and watch a leaf in the wind for a very long time. Are you working all the time, or does it ebb and flow?

RIST: All the time. [laughs] I’m looking for some ideas on how to relax more.

SCHNEEMANN: A good cat is full of inspiration, and a dumb cat is just as nice. I have one very dumb cat that I rescued. She only thinks about food. Then I raised this kitten, who is such a genius—she makes art, and has an incredible imagination. The older cat was completely bewildered. She just looks at me and then looks at this inventive cat, like, “I don’t understand, what’s happening?” Do you have a lake where you can swim?

RIST: Theoretically, yes. We have a beautiful lake here. Doesn’t your last name have the German word for snow, or cold water, in it?

SCHNEEMANN: Yes, cold, brilliant, icy water. I made that name up. Carolee was my name, but not Schneemann. When I was really young, I saw there were no female painters, there were no female artists. But I saw that the men had big names, so I thought, “I need one like that.”

RIST: Choosing a name is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Okay, my last question: What’s the best piece of advice?

SCHNEEMANN: The best piece of advice I’ve been given, or that I can give?

RIST: Either. The question is open.

SCHNEEMANN: An older friend once told me, “Life didn’t ask for your opinion,” which I liked. And my best bit of luck was to have met James Tenney and to have had this wonderful partner in the early days for 12 years. He was a musician. We’d listen to Ives and Ruggles and Varèse and Schoenberg, and have these wonderful discussions about sound and images all the time. Because of him, all the other rejections around my work didn’t feel completely enclosing. I guess my best advice is this: Be stubborn and persist, and trust yourself on what you love. You have to trust what you love.

PIPILOTTI RIST IS A ZURICH-BASED VIDEO AND INSTALLATION ARTIST. A MAJOR SURVEY OF HER WORK, “PIPILOTTI RIST: SIP MY OCEAN,” OPENS NEXT MONTH AT THE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART, AUSTRALIA.