A Few Sex-Positive Feminist Artists, Once Misfits

Nearly a quarter of a century since third-wave feminism rolled in, its tenet of sex positivity, wrapped up with celebrating the female body, is taken for granted. Not long before that, however, in the 1960s and 1970s, prevailing second-wave feminist arguments favored censorship, with the belief that when the female body was depicted in a sensual way it would inherently be objectified by the male gaze of the patriarchy. As a result, the most lauded artists of second-wave feminism engaged with the female body only tangentially or metaphorically– take Judy Chicago’s seminal work The Dinner Party (1974-1979), comprising dozens of yonic plates representing famous women. Artwork by self-identified feminists that championed brash eroticism, though, was sidelined.

Now, an exhibition at the Dallas Contemporary showcases the work of four artists who gravitated towards the latter despite criticism–Joan Semmel, Anita Steckel, Betty Tompkins, and Cosey Fanni Tutti–in “Black Sheep Feminism: the Art of Sexual Politics,” curated by Alison M. Gingeras. Each artist, in her own way, explores nudity by presenting women’s sexuality as an inevitable fact, and one not mutually exclusive with female empowerment.

The idea for the exhibition came along as Gingeras was working on an essay about Jeff Koons’s infamous “Made in Heaven” series, in which Koons depicts himself having sex with his then-wife, the porn star-turned-politician Ilona Staller. Gingeras argued that the series owed its concept to earlier works by women artists, and this led her to research the artists now featured in the show. They had all been largely left out of mainstream feminist art history, she discovered, but the explicit nature of their work resonates with the artwork of young women today who self-identify as third- and fourth-wave feminists. Petra Collins and Sandy Kim, for example, have both documented their own bodies in graphic ways (Collins posted a photo revealing her pubic hair on Instagram; Kim has photographed her menstrual blood on her body) in attempts to normalize naked female bodies, and fight their exploitation.

With such works by young artists becoming commonplace, it made sense to Gingeras to revisit these four artists, who were “marginalized even within the progressivism of the feminist movement,” she explains. As one criterion, Gingeras points out their exclusion from (Tompkins and Steckel) or downplayed contribution in (Semmel and Fanni Tutti) the 2007 exhibition “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution,” which angled itself as a definitive survey of second-wave feminist art.

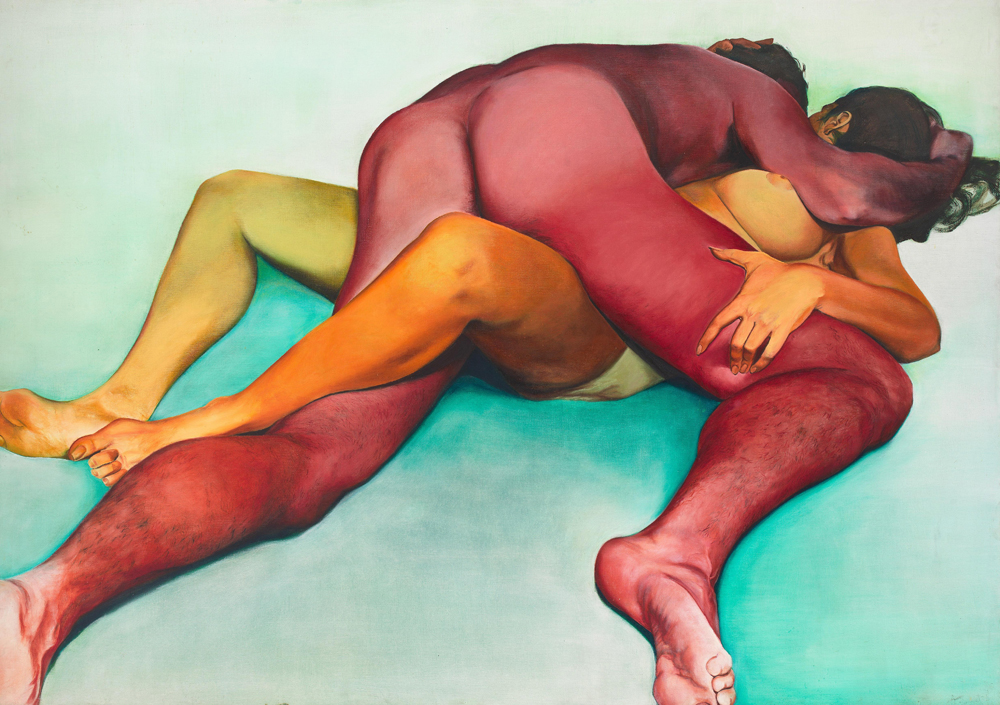

Tompkins, whose “Fuck Paintings” depict close ups of genitalia during heterosexual intercourse, was widely censored in the 1970s, and the original series was not exhibited together in New York until 2002. Today, she is experiencing a surge of popularity, and it’s probably not a coincidence that her work is mistaken for that of a younger woman artist. Semmel and Tompkins clashed in the ’70s because Semmel disagreed with Tompkins’ approach. Although Semmel paints erotic scenes, often of couples having sex, she does so in soft, often nonrepresentational colors and with less intense detail. Steckel, who died in 2012, worked across mediums and founded the “Fight Censorship” group; she wrote in the manifesto, “If the erect penis is not wholesome enough to go into museums, it should not be considered wholesome enough to go into women.” Gingeras included a few of Steckel’s oil paintings, three of which depict giant women frolicking among and straddling the skyscrapers on the New York skyline. Fanni Tutti, the group’s only performance artist, started out as a porn star, declaring herself an artist with the exhibition “Prostitution” in London in 1976, which presented pornographic photographs of her as her own art.

In the space at Dallas Contemporary, Gingeras arranged the works to juxtapose one another, highlighting various similarities and differences. “I think that each artists represents, within this one terrain of Eros, very different tones and strategies. So there’s this interesting complexity between the four,” she says. The broader relevance of the museum’s location in Dallas, Texas was also not lost on her. “The advancements and achievements we were able to take for granted [after second-wave feminism] are under fire again, in terms of real-life politics,” she says, citing reproductive rights as one example. “It’s an election year…hopefully this will show be successful and thought provoking for people.”

“BLACK SHEEP FEMINISM: THE ART OF SEXUAL POLITICS OPENS ON JANUARY 17, AND WILL BE ON VIEW THROUGH MARCH 20, 2016 AT THE DALLAS CONTEMPORARY.