Belgium’s International Pavilion

VINCENT MEESSEN IN VENICE, ITALY, MAY 2015. PORTRAIT BY CARL J ASQUINI. SPECIAL THANKS: KODAK ALARIS.

At the 56th Venice Biennale, the Danish Pavilion is showcasing works by Danh Vo; the American Pavilion, Joan Jonas; the British, Sarah Lucas; and the Icelandic, Christoph Büchel. In other words, the majority of national pavilions present works by one representative artist or a singular collective. This year, however, the Belgian Pavilion breaks with tradition. Rather than just exhibiting his own works, the selected Belgian artist, Vincent Meessen, worked with curator Katerina Gregos to bring 10 additional international artists into the show, including Sammy Baloji, James Beckett, and Adam Pendleton. The group exhibit, “Personne et les autres,” explores political, historical, cultural, and artistic interactions between Europe and Africa during both colonial and recent times.

“Modernity has created this idea of primitivism,” Meessen says. “[Identity] is only a projection of what you have inside you.” The Baltimore-born and Brussels-based artist maintains dual citizenship in America and Belgium, blurring the lines of his own national identity. “If you look at it like this, you could say there’s not a Belgian in the Belgian Pavilion,” he continues.

Sitting in the center of the pavilion is Meessen’s three-channel video installation, One. Two. Three., which reinterprets a largely unknown protest song, written by former Situationist Joseph M’Belolo Ya M’Piku. Surrounding Meessen’s installation are the other artists’ works, including a room covered from floor to ceiling with black-and-white, Dada-inspired imagery made by Pendleton, a New York-based mixed media artist.

After the opening reception of the pavilion, we spoke with Meessen and Pendleton to learn more about the process and the artists themselves.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: How did you first become interested in bringing together artists from around the world?

VINCENT MEESSEN: It all started with the discovery of lyrics from a song written by a Congolese student affiliated with the Situationist International. He was a student of one of the four most important thinkers from this movement. This Congolese component, although it’s very short, is completely unknown. I started with this idea that I would do research to find this guy, and if he was still living I would make something out of the song.

I went back in Kinshasa, found him, and he accepted the idea to make this work with me. Then I worked with Vincent Kenis, a musical producer who is very famous—got a Grammy nomination and BBC Award for working with Konono No. 1—and still works in the Congo. So we went there and made this video, but the moment I thought, “I’m going to present this as a project for the pavilion,” I also thought it would be much more interesting to invite other people and think about internationalism. After the break of the [Berlin] Wall, after ’89, it was like internationalism went to the dustbin, like it never existed. The idea was to look at the presence of Belgian people, artists, thinkers, in the international avant-garde from modernity, starting in Dada.

MCDERMOTT: There was clearly a lot of organization and research to bring everything all together. What was one of the biggest challenges you faced?

MEESSEN: Not being only the artist, but also the producer of the pavilion. It means that the project is not only an artistic project, but it is also an economical project—sharing costs a lot of money. It was a lot of stress and non-artistic work that took a lot of energy.

MCDERMOTT: Is there a moment you remember as really formative or helpful?

MEESSEN: One of the most striking elements was when I was in Kinshasa to shoot my film—I had been there three times in order to organize, to rehearse with the women, but when we went with the whole film crew, we were trapped in an insurrection, riots with a lot of people killed. That was dramatic, but also, at the same time, making so much sense with what I was doing there. We were trapped in this rumba club, but at the same time we would hear policemen shooting just outside.

Everybody told me, “You have to stop.” My partner called me and said, “Vincent, it’s going to be a really hard time. You have to go back to the hotel. Nobody will come.” The city was dead. I said, “Look, I have six days. I have to shoot my film.” The musician came and we did it, but it was a very strange moment.

This seems like it could be seen as an exhibition related to colonial history, but it’s really how we process it in the present. In my film, we’re connecting with a situation now in Congo, trying to think about heritage as a political pretension that can be put to the test. It’s not only an artwork, but it’s something that’s active. There’s a kind of urgency in the pavilion, and also sometimes a bit of violence, like at the end of the film. Rumba is really a form through which [the Congolese people] can express a lot; it has this catharsis. When you go into Kinshasa, you live in music the whole day and night. Even when you go to sleep, there are bands playing.

MCDERMOTT: How did you deal with the ethical issue of making an art film while these riots were happening?

MEESSEN: That was the hard point. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t want to stop because I was obliged to do it somehow, but I knew there were real bullets. So you do it and you think, “Maybe they’re gonna come here,” and police are less trustworthy than the people. You better trust the demonstrator and not the police. It was a strange atmosphere because I’m not a war journalist. That’s not my business. You think you are working with history, but the present is always stronger. Realism is stronger than fiction. You have to be aware in order to understand what’s happening, to capture it and use it in art.

MCDERMOTT: So how did you find this unknown song?

MEESSEN: I found it in an archive of a former Situationist. The writer himself, he didn’t even remember that he wrote it. When I read the lyrics, there was a French translation, and I immediately saw how interesting it was. There is only one name known as a Congolese member of the Situationist movement, and nobody had worked on that before. After months of research—finding family members, the sons of the other Situationists who died in the late ’80s—I made some interviews and knew I was coming up with something strong in terms of unknown history.

An important thing I forgot to say, is that the last Situationist conference took place in Venice in 1969. After that the movement collapsed. There are a lot of stories that bring together this art scene and colonial past. It’s very interesting how in the end it all comes together. There are many links between different works. Sometimes it’s formal, sometimes its layers into the history. Even reading [the book that accompanies the catalogue] you will realize new connections that are not visible.

EMILY MCDERMOTT: What do you think about national representation, both as an American and as an American in the Belgian pavilion?

ADAM PENDLETON: It’s interesting, because I just came out of Okwui’s [Enwezor, curator of “All the World’s Futures”] show and there’s so many overlaps between the gestures that Katerina and Vincent have made and what Okwui is trying to do. They all seem to be playing with ideas of not only national representation, but representations of self, in terms of sociopolitical realities, and extending beyond that into poetic spaces. There seems to be a breakdown or deconstruction of “I am representing myself,” or “I am representing a nation,” and it seems to respond to or be more representative of our 21st century dynamic, where things are perpetually in flux.

MCDERMOTT: Globalization.

PENDLETON: Yeah. I think the parts that relate to technology and changing mechanisms of communication, and the layering of identities, influences, histories, and images, you end up in this really poetic space, which, for me, is this incomplete space, this ethical space, if you will. There’s something ethical about incompleteness or perpetually “becoming.”

MCDERMOTT: How do you explore this ethical issue?

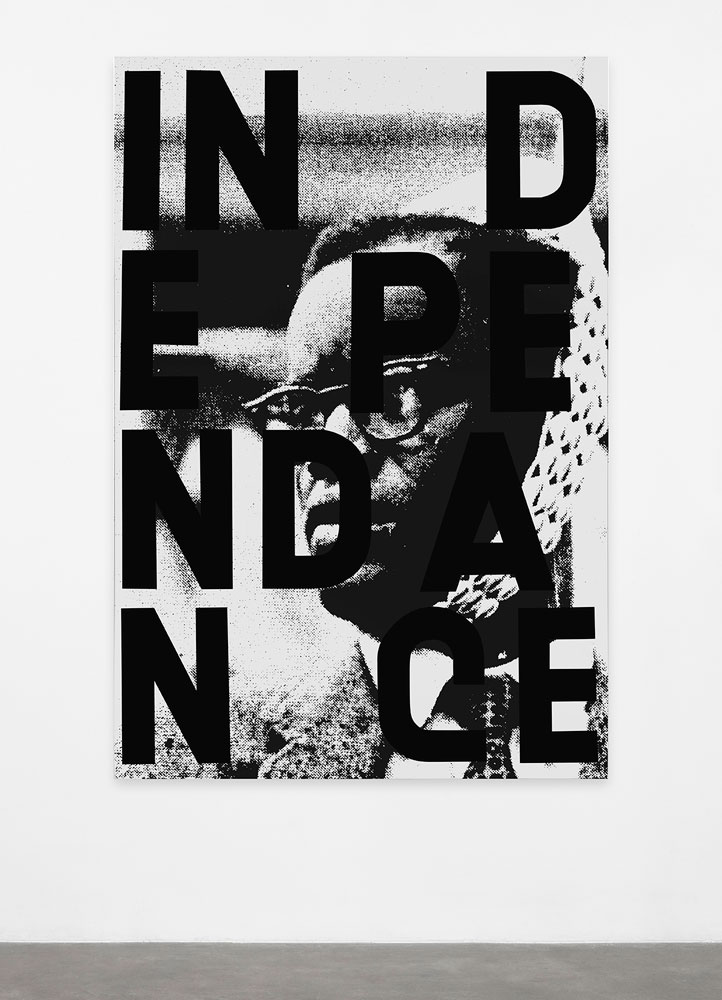

PENDLETON: One of the primary ways that I toy with this idea of representation in my own work is that I’m perpetually trying to disappear. At times, it’s an experimental portraiture, but grounded in this idea of black Dada, which is an overarching concept that gives a foundation to the conceptual, theoretical, and aesthetic gestures I make. What’s rewarding for me here, presenting work in the Belgian pavilion, is that I’m able to see those gestures in relationship to what other artists are investigating and developing.

MCDERMOTT: How do you personally view nationality?

PENDLETON: Outside the pavilion there’s this flag [I made] that says “Black lives matter,” which is echoed in the installation inside the pavilion. I think when an American says that it means one thing, and then when a Belgian says that statement it means another thing. It’s nice that things can have these multiple meanings and these plural meanings; I feel as though I’m not tied to any fixed sense of nation. But, that said, there is ultimately something very American about what I do. [laughs] I don’t particularly deal with nationality in regard to my work, because my work pulls from a variety of a wide web of references: I reference conceptual art, which obviously was and is a global movement; I reference African independence movements that specifically relate to countries in Africa. In other words, we can all relate.

MCDERMOTT: When you’re referencing these movements, how are those seeds planted? Where do the ideas begin?

PENDLETON: Oftentimes a point of departure is an image. I have quite an extensive library, so it’s often about going through books, and being a visual person, an image will strike me. Then I’ll do quite a lot of research and reading about where an image comes from. This piece for me, there’s something encyclopedic about it. It’s kind of an archive; it’s a kind of a library. It breaks down and asks questions about how those things function.

MCDERMOTT: Was there a specific image that sparked this installation? There are obviously quite a few images involved.

PENDLETON: These are images that I’ve been using in my work for seven years or so. They’re perpetually interesting to me. I’ve used them to make paintings. I’ve used them for my book projects. I pin them to the walls of my studio. In different circumstances they take on different meanings and that fascinates me. Looking at these images here, in relation to the other artists in the pavilion, brings different things to the foreground. There’s so much potential in an environment like this, where people are looking and thinking seriously about art and what it can do in regards to civil society—or not-so-civil society.

“PERSONNE ET LES AUTRES” IS ON VIEW AT THE 56TH VENICE BIENNALE IN THE GIARDINI THROUGH NOVEMBER 22.

For more from the 56th Venice Biennale, click here.