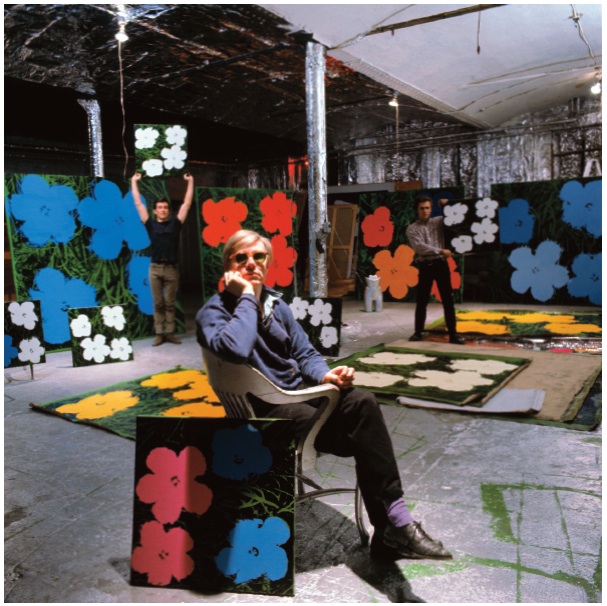

Andy Warhol’s Flower Power

At the 1964 New York World’s Art Fair, the architect Phillip Johnson commissioned 10 artists to make large-scale works to adorn the facade of the State Pavilion—a monument Johnson had designed as a celebration of human advancement. Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, James Rosenquist, and Robert Rauschenberg were among the Pop artists selected. Andy Warhol was another contributor. However, Warhol’s piece Thirteen Most Wanted Men, which depicted silkscreened mug shots of real criminals, was censored—covered with silver paint, and never seen by the public.

Was this event the catalyst for Warhol’s transition from felons to florals? The flower, a symbol of fragility and purity, is antithetical to the blunt violence associated with the criminal. The art historian Michael Lobel eloquently explores this collision of themes in Warhol’s work in his essay “Andy Warhol Flowers;” a fitting accompaniment to the comprehensive survey of Warhols’ Flowers paintings that will be shown at Eykyn Maclean from November 1 through December 8, 2012.

Warhol’s flower paintings, created between 1964 and 1965, were initially inspired by a photograph of several hibiscus flowers taken by Patricia Caulfield, then the executive editor of Modern Photography magazine. The foldout article depicted how a new Kodak home color processing system could manipulate color. Warhol appropriated the image, cropped, copied, enhanced the contrast, and eventually settled on a square format that meant the paintings could be viewed from any orientation. A collection of these paintings was the focus of Warhol’s first show at the prestigious Leo Castelli Gallery in late 1964, and signaled his ascension into the legitimized art world.

At Eykyn Maclean, viewers will have an opportunity to revel in Warhol’s vibrant color palate and bold graphic sensibility, experiencing, somewhat fleetingly, Warhol’s two-year floral obsession for themselves.

For more information, visit the Eykyn Maclean website.