Ai Weiwei

China doesn’t have any books on the student culture revolution because they consider that antirevolutionary. Ai Weiwei

For the past decade, the art world seems increasingly preoccupied with finding and coronating an heir to Andy Warhol’s legacy. That distinction has, over time, gone to everyone from the reigning Pop masters of the shiny and commercial, to the young, grungy downtown painters of the unshiny and commercial. But perhaps the artist who most embodies Warhol’s wit, prodigious artistic maneuverings, spirited distortions and amplifications of the cultural status quo, and his rare agility at gathering people together in openness and defiance might very well not be found in New York City or in the United States or even in the Western hemisphere. He is Ai Weiwei, and not since Warhol has one artist brought so much revolutionary activity to the act of art-making. If Warhol’s activity targeted gender codes and brilliantly conflated the elite with the masses, 56-year-old Ai Weiwei’s cogent multimedia productions thrust the individual out of the multitude and personal freedom out of the state machine.

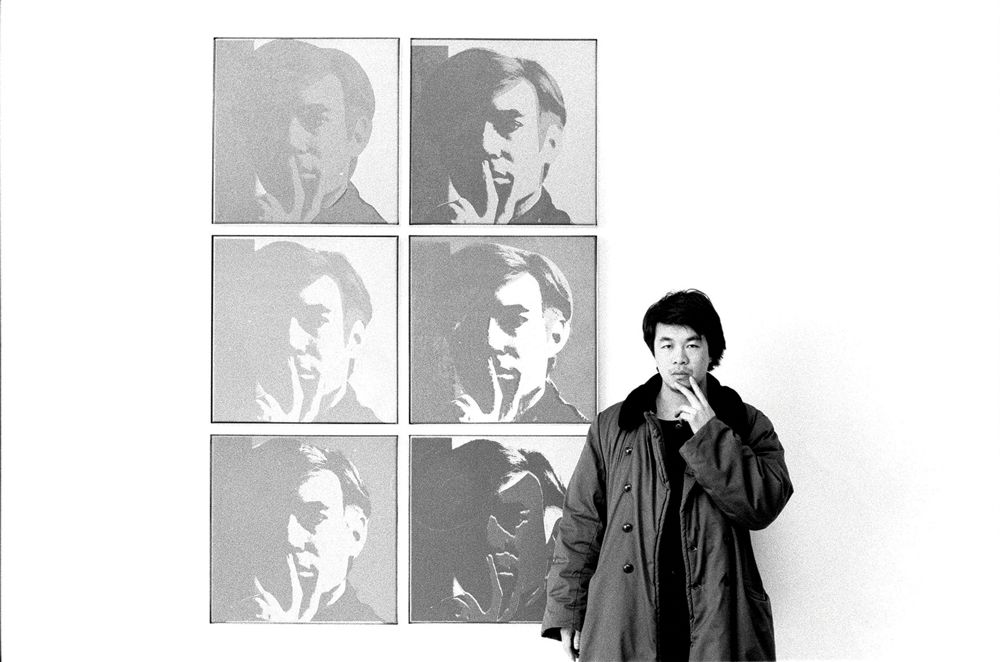

Ai Weiwei, the son himself of a dissident artist, the Chinese poet Ai Qing, grew up in remote northwestern China, excommunicated from the internal affairs of Beijing due to his father’s political exile. He reached New York City at age 25 and quickly took to the Manhattan art and social scene as if it were his native soil. In the nine years he lived in the East Village, he crossed paths with counterculture luminaries such as Keith Haring and Allen Ginsberg, studied the radical impact of modernists like Warhol, and began producing his early works—among them, black-and-white photographs of urban life and a telling portrait of the ready-making-master Duchamp out of a bent coat hanger and sunflower seeds. During his extended time in the West tending creative seeds, his homeland was spouting—and quashing—its own political seeds, in particular, the spring 1989 youth demonstrations for increased personal liberties in Tiananmen Square that ended in staunch military intervention and hundreds, if not thousands, outside of the square dead. (In some ways, it has only been Ai Weiwei’s work—and figure—that has visually supplanted the iconic image of the unknown man standing in front of four tanks on Chang’an Avenue as the symbol of civilian resistance to Chinese authority in Western consciousness.) Ai was in America during that key conflict, but its fallout—a tightening of security measures and a silencing of dissenting opinion—would eventually serve as a canvas for him to apply his strokes. Ai returned to China in 1993, at the age of 36, three years before his father died, but it would be another decade before his visual productions resurfaced on the global stage with keen conceptual and political precision.

Today, Ai works and lives in his walled compound in the Chaoyang District of Beijing. Persimmon and pine trees and bamboo fill the courtyard, lush green ivy climbs the walls, and many cats—a few shaved like lions—stalk the grass or lie in the sun. Ai built the studio for himself in the late ’90s—his first foray into architecture that would lead to his collaboration with Herzog & de Meuron on the “Bird’s Nest” stadium for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. Inside the compound walls, Ai’s activities seem both industrious and monastic. It is from here that he works on the plans for several projects—sculptures, installations, large-scale outdoor ventures approaching Land Art, films, tweets. But for a man who may be the most famous and relevant artist working right now, it is a very small corner of the world he is allotted with too little immunity, if any at all. Across the street from the studio is a common white surveillance camera (decorated with a traditional red Chinese lantern) aimed directly at his door (such cameras are found all over Beijing). Like many Chinese citizens, Ai has been routinely thwarted in his use of social media. In recent years, Twitter has been his most salient tool of global exchange. Ai is not allowed to travel outside of China—not by some official proclamation after a trial, but like most forms of governmental decision approaching terror, by some vague intermediary verdict for an indeterminate time with no recourse of contestation.

Ai has long utilized homegrown Chinese artifacts, practices, and forms in his productions, whether shattering a Han Dynasty urn on the floor, creating assemblages of bicycles into elaborate geometric formations, or bringing 1,001 Chinese citizens, most of whom had never previously left the country, to Kassel, Germany, for Documenta. But it wasn’t long after the construction of the “Bird’s Nest” that Ai’s unabashed freedom of expression started to turn the unflattered ears of the Chinese government. His vocal outcries against incidents such as the displacement of migrant communities for the Olympic Games, the hushed-up death toll connected with suspect building practices in the devastating 2008 earthquake in Sichuan, and the imprisonment of writer Liu Xiaobo begat a campaign of censorship and strict—sometimes bodily injurious—containment. When the state decided to tear down the artist’s studio in Shanghai in 2010 as punishment for his refusal to keep quiet, Ai responded by organizing a party for its demolition (on the menu were crabs, a loaded reference to the Chinese word meaning “harmonious” that is a homonym for “river crabs”). Just as, half a century ago, Warhol took the idea of American freedom and extended it in his films and canvases to show just how free individuals could be (“You want full freedom, I give you Candy Darling”), Ai Weiwei took the state’s demand for harmonious conformity and one-upped it (“I will acknowledge your decision to punish me to the point that I will actually host a party for your destructive reprimand”). In 2011, as Ai was at the airport about to board a flight bound for Hong Kong, he was arrested and held indefinitely in prison on the speculatively trumped-up charges of tax evasion. Following a global clamor for his release, he was freed after 81 days, fined (15 million yuan, about $2.4 million), and was made aware that he could be re-arrested at any time. This is where the story leaves the Warholian and begins to enter Orwellian.

The state can do whatever it likes. It teaches the person not to make any arguments. But my situation is very different. I see it as

a great opportunity. Ai Weiwei

This summer during the Venice Biennale, Ai showed six fiberglass dioramas, scaled to half-life-size, that encapsulated scenes of his time in prison—eating, on the toilet, in bed, always with two guards peering at him at uncomfortably close range. The resulting claustrophobia is a visceral reminder of the conditions that those who speak out must endure; the repercussions faced by a man who continues to make art when each day, each minute, each step outside of his studio door, each tweet, could end in arrest and imprisonment. Ai continues to plan for the future—in June he opened “Out of Enlightenment” on the shores of the Emscher River in Germany; another gesture of inclusion, around 1,000 igloo-like tents are inhabitable by anyone who wishes to stay in them and enjoy the natural scenery in an area previously left destitute by the downturn of the steel industry. And unlike the mining of the land, when removed, Ai’s living installation leaves no trace behind. It is also nearly impossible not to think of his ongoing tweets and Tumblr posts as part of his art practice—subjects ranging from the possibilities of digital media and the treatment of Chinese dissidents to updates on his heavy-metal album. Like Warhol, Ai is an eager practitioner of any new technology to get his message across, helming a factory in the most traditional and most radical senses of the word. If there is any speculation in the West that Ai Weiwei the social critic has eclipsed Ai Weiwei the visual artist, it is only because, in recent decades, the idea of art as a political act—or, at least, an arena for political debate—has been bred out of our understanding in favor of more marketable formalist values. Ai’s work shows the possibility of its return—that for him now, and maybe for us in the future, speaking one’s mind, expressing one’s point of view, making and disseminating work that doesn’t fit the apparatus of a controlling system, is political.

In early May, shortly before the Venice Biennale, which Ai could not attend, I visited him at his Chaoyang studio in Beijing. We sat outside at a glass table, which held an ashtray shaped like the “Bird’s Nest” stadium and a sleeping white cat.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN: You moved to New York in the end of 1982.

AI WEIWEI: Around Christmastime. I studied for half a year at Parsons. And I spent some time at the Art Students League. But I spent most of my time in the Lower East Side.

BOLLEN: That must have been something of a seismic shift for you coming from Communist China to the East Village in the early ’80s. Were you prepared for that kind of cultural dissonance?

AI: I grew up in a very, very poor, very politically restricted area, which is in northwest China. If you think of China being like a map of the United States, New York is in Beijing’s position. But I grew up in what would be Washington State. The very other side of there. [laughs] Near Russia in the Gobi Desert.

BOLLEN: You grew up there because your father, the poet Ai Qing, was exiled there because of his political beliefs—he was accused of “rightism,” which is a sort of liberalism. Obviously, even in the Gobi Desert you were influenced by a very artistic family. But did you have any exposure to modern or contemporary art at all growing up?

AI: No, not at all. My father talked of art, such as the Impressionists, because when he was young, he went to Paris and studied art there and was very good. So I had a strong impression from him on early contemporary art but very limited sources. I still remember before I went to the United States, they gave me a translator and you can have a few books, but even then, the whole of China doesn’t have any books on the student culture revolution because they consider that antirevolutionary.

BOLLEN: As a child, did you have inklings of wanting to become an artist based on what your father was describing?

AI: Yes. But at the same time, my father refused to let us become so-called artists. You know, at that time China had no artists anyway. They were called “art workers.” Even during my detention two years ago, they asked me, “What’s your profession?” I said, “Artist.” They said, “Ha, ha. You can’t call yourself an artist.” I said, “So what do you call me?” They said, “At most, you are called ‘art worker.’ ” I said, “Okay, I’m an art worker.” I like the name very much, but no one calls themselves “art worker” anymore. [laughs]

BOLLEN: I guess the point is that if you’re an art worker, you’re still working for the state. You aren’t floating off in your own direction.

AI: Yeah, you’re just one of the screws on the big machine. An artist is more independent.

BOLLEN: Much of your education happened in New York. That kind of rapid Western immersion must have been profound.

AI: Yeah, I was totally sucked into it because, first, I love the metropolitan. I grew up in a semi-military base. We didn’t have lights, not even candles. We had to light this kind of oil, gas, but it’s very dark. Every night your nose becomes so dark from breathing it in. It’s very bad quality. So I just love the light. And on the plane, before I landed, it’s about nine o’clock in the evening, and I saw all of New York start lighting up. I was so touched. I thought, This is the place I will die for. And there’s this kind of energy, this imagination, to see what kind of people created a place like this. So I was just completely in love. I think it’s the same kind I love that Warhol had when he left his hometown of Pittsburgh. He must have had the same feeling.

BOLLEN: I think that’s what New York is for any immigrant—domestic or foreign—that kind of melting into the shine of the city.

AI: Yes, bright lights, big city. The first book I read was The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again). I was very limited in starting to learn English when I read it, but I thought that book’s humor was completely funny and cool. I thought, This guy is so cool and just amazing. And I was seeing his art at the same time. He’s so sensitive and so uncertain, but with a lot of humor. Even if you look at that book today, he’s still decades ahead of his time. Now I’m working so much on Twitter all the time. What are the sentences that I can put on Twitter—very short but very smart and witty, and sometimes shocking. Well, a lot of time it may be just nonsense …

BOLLEN: I think a lot of people underestimate Warhol as a writer. They think of him as just a kind of savant, but even beyond the visual production, he was poetic in a lot of what he said and wrote.

AI: Yes, so contemporary and so unique. He really was a poet in the sense that there was no limit and no restrictions for him. It just came out very naturally and very innocently, sometimes in a naive way, but beautiful and vulnerable.

BOLLEN: Did you ever run into Warhol in New York in the ’80s?

AI: He was not going to openings so much by then. But sometimes at a gallery opening he would be there. I never personally met him. I still remember at that time people like Keith Haring respected him so much as a figure, but he was less active by the time I got there.

BOLLEN: He was also rather unpopular in the ’80s. There was a moment in the ’80s when one could have thought that he would be irrelevant in the years to come. His work had fallen out of style a bit and maybe also his flamboyant ’70s appeal. There was a low Warhol moment. As it turned out, it was just a moment.

On the plane, I saw all of New York lighting up. I thought, this is the place I will die for. Ai WeiweI

AI: Yeah, it’s true. He started doing his TV show, Andy Warhol’s 15 Minutes, and he wasn’t very popular, and he was doing advertisement campaigns.

BOLLEN: Did you find yourself influenced by the young art stars in New York in the ’80s? Did you have much contact with some of those painters rising to fame at that time?

AI: Almost no contact. The ’80s was quite a lonely time. You had big stars like Julian Schnabel and the Mary Boone artists—the 50 big stars—but they were so different from the ’70s artists.

BOLLEN: You took a lot of black-and-white photographs while you were living in New York, from the Tompkins Square Park protests to Allen Ginsberg. But I remember one self-portrait you did in the nude standing on a chair in your apartment on East Third Street. I happen to live on East Third Street now. I try to imagine how different East Third Street must have been for you in the mid-’80s than it is for me in 2013. Do you remember it well?

AI: It was really rough. I remember one little rainy day I went searching for this apartment and I saw so many people standing on a stoop on the corner in the rain. Later I realized, that was drug traffic. They were all buying drugs. So in the ’80s, you couldn’t walk in the neighborhood without looking back to see if anyone was following you. You had your key in your hand before you got to your apartment and you’d rush in so you didn’t have to stop.

BOLLEN: Did a city of random crime after growing up somewhere so governmentally protected shock you?

AI: It just fit my image of what a city should be—the super-rich and all the poor and desperate and the people who have some kind of a desire. It’s a surviving game, people trying to survive on many different levels.

BOLLEN: You were in New York during the student uprisings at Tiananmen Square in 1989. I know you protested in New York in solidarity, but it must have felt like you were very far from the people your age in Beijing. Did that upset you or were you glad for the distance from all of that?

AI: When I left China, on the way to the airport, my mom was really worried. This boy doesn’t speak a word of English. He has no money, maybe a few hundred in his pocket. What is he trying to do? I said, “You will see another Picasso in 10 years.” They all laughed, even my classmates. I sounded kind of crazy. And once I was in New York, I completely had no interest for a long time in what happened in China because I had been through so much. Seeing my father’s life struggle and so many whole generations lose their potential or possibility in their lives. Just being pushed into this political struggle and the damage done not only to their lives but their relatives. I said, “This is not for me. I have to find a place for my own. I have to search for my own happiness.”

BOLLEN: If your father had not been sick in 1993, would you have ever returned to live in China?

AI: I had no reason to come back.

BOLLEN: And instead you’ve inherited a similar burden to what your father faced.

AI: Warhol said something like, “Be careful what you want, you may actually get it.” I hate this so much, but I’ve become very political, or at least considered by many to be so. I had no reason to come back. Although it’s hard to imagine what would have happened if I hadn’t, because I have nothing to do in New York now, even though I spent over 10 years there. New York is a city where you’re so alone, you’re an individual, you can disappear. You can make something happen. But it’s very different to make something happen in the art world.

BOLLEN: This is something I want to discuss. There is a rather perverse irony of your position and influence in the art world today that others envy. Your work has its rigorous formal conceptual qualities as stand-alone pieces, but there is a very loaded political aspect to your work, which is often sewn into the material or structure of your work—the steel rebar from the Sichuan earthquake school building collapse of 2008 or the children’s book bags found in the aftermath as just two examples. I think there’s this prevalent idea, at least in the New York art world, that art has lost its power to incite or critique. Straight white male artists can’t really do much more than play with formal or conceptual elements to death because there really is no way for them to articulate an artistic critique of the system—unless it’s a tricky negation by promotion, like Jeff Koons. An I’ll-celebrate-excess-until-we-all-drown-in-it sort of maneuver. But I think in the increasingly wealthy market of the New York art world, there’s a paranoia that it’s all a bunch of empty gestures. What is your take?

AI: There are a lot of empty gestures, yes, because there is not this necessity for many of those people to even struggle. I think Warhol was very different from that. Warhol came from an ordinary family and he had a profound understanding about capitalism and material culture. He was probably one of the few Western artists—or artists from the United States—that could be considered a true product of his time and brought out that kind of spirit of the culture. You see so many people doing quite nice and respectful work, but nobody like Warhol. Warhol is outstanding. I think he has a value that is far from fully understood. He’s very special for younger generations.

BOLLEN: He subverted the system by using the system, which you can’t really do the same way because the system you’re dealing with is built with limits from the start. So you found new systems for subversion—social-media technology being one. But I guess I’m asking, do you purposely strive to create political tension or resistance in your work? Is that a condition on which you begin to fashion the specifics of a piece?

AI: I think I’ve been given a lot of reason to study it. You cannot just assume it’s a sin or a crime or whatever. You have to be somehow involved. You have to use your own experience to tell a story. Every day I’m learning something new from the practice. It’s very rewarding. It’s not that I’m using the condition, but rather that I’m using it as a ready-made, like Duchamp did. You see the object from another angle, which you can dismantle from its original meaning or function to come up with a new definition.

BOLLEN: Like your stools or ancient Chinese urns or book bags—the phenomenology of a cultural object. Except for you the ready-made is often Chinese politics.

AI: Chinese culture or the Chinese political situation today gives me this kind of opportunity. And of course I have to be very careful. First of all, I don’t want to be hurt. I have been hurt quite dangerously several times. But I don’t want to be deeply vanished by an overjoy of this game. It is a kind of game. You have to maintain yourself in the game and not outside of the game. But it’s a quite dangerous game. Secondly, you cannot be taken away by this joy. You see people who are very skillful, very artful, but who are taken away by it and have lost the proportion of life. Life is not only about that. You still have to have a very good heart like Warhol did. He said, “An artist is somebody who produces things that people don’t need to have but that he—for some reason—thinks it would be a good idea to give them.” I think he puts it very nicely. My situation gives me certain ideas about beauty or the excitement of life, but that doesn’t mean other people can necessarily appreciate it. And again I have to be very careful about that.

it is a kind of game . . . But it’s a quite dangerous game. Ai Weiwei

BOLLEN: Much of your work appears large-scale in other countries—Italy, Germany, the United States. These are all places you aren’t allowed to travel to in your current situation. Is that a challenge, to make art for display in places you can’t actually visit?

AI: It’s not much of a challenge in today’s world. I live in Beijing, but New York or Berlin is just blocks away. Communication is so much better because of the internet. I can write e-mails, I can Skype, and people travel here frequently so it’s not that difficult. I also think it’s more interesting because of this restriction. I have to build up another kind of communication, first with my own team. They all have to understand what is on my mind. I have to explain clearly. I have to pick concepts, which can be clearly expressed and be assembled without me. It’s a unique position.

BOLLEN: You also manage to work on a number of projects at once. You’re not a one-at-a-time artist.

AI: I remember when I would go to Atlantic City, for hours I’d play a few hands of blackjack at once, because one hand takes too long to come back. A few hands at once, you are always gaining or losing. You keep it even by playing like that. [laughs]

BOLLEN: You are under constant surveillance. Do you feel restricted in the freedom of what you can make, even if it is slated to be exhibited in another country?

AI: Often the smaller the space, the more freedom you have. Like a housewife pulls a few vegetables out of an garden, she can still make a beautiful dish, better than any restaurant. It’s not really about how much you have, but rather about how much you make out of it.

BOLLEN: Are you even allowed to show your work in Beijing? Or in greater China?

AI: The situation is mixed. For example, I have been accused of owing the state 15,220,000 yuan in tax. That’s a number that the whole of China has never heard of. The first quarter’s profit of Sina, the big media icon, is less than that. Everybody finds this shocking. Under what kind of logic can the state police do something like this? And yet even under such a big case as this, there’s not a single Chinese media outlet that presents one word about it. If someone grabs someone else’s bag, it would be in the newspaper. But my situation they cannot openly talk about. That’s how they crush the political opposition, to use some other kind of crime, whether it’s rape or a tax. Most people will think, “Oh, this guy is not such a reliable guy, he’s a liar.”

BOLLEN: They trump up a crime to discredit opposition.

AI: Not only to discredit but also to leave the one punished in such a sad situation that they see that the state can do whatever it likes. It teaches the person not to make any arguments. But my situation is very different. I see it as a great opportunity. So I say, “Okay, you accuse me of this. Let’s sit down and calculate it. Where is the evidence? How do you make this accusation?” And by doing that, I have put down a big deposit, which they never imagined I would do. Eight million. So, on the internet, people start to give us money.

BOLLEN: Yes, I read that it’s like a way of voting for people. They can’t vote but they can send a dollar as a form of voting, of backing an oppositional party.

AI: They will say I will not buy a pair of shoes next month because I want you to have this money. Because it’s our voting ticket—although they never see a voting ticket. In about 10 days we gathered nine million through 30,000 people. That’s a miracle.

BOLLEN: That’s incredible.

AI: The state is shocked. Because now they don’t know what to do with this guy. But I feel so happy because all I did was try to encourage young people to see it’s not that you cannot do anything about it. You just have to do something to make yourself happy. Then these kinds of states, they cannot last. But if you totally give up, that’s another story.

BOLLEN: What is the end game in terms of what you’d like to see in China? Do you see a day when China could be more “constitutional”? Or having more than one party in command?

AI: I’d rather not even think about that. I think Warhol put it very nicely when he said, “A place that has no McDonald’s is not beautiful.” I think by not letting young people be fully informed, how can they have energy and passion and the right picture of the world? I think that’s the true crime. This world should be much more open and should be much more free, so the young people would have the chance to exercise the quality of their lives.

BOLLEN: Lately, the new leader, Xi Jinping has borrowed a favorite American expression, calling for the fulfillment of the “Chinese Dream,” which is, I suppose, a retooled rendition of the American Dream.

AI: Yeah, they’ve tried to blur that. They like to say that China has a dream. But it’s so empty. There’s nothing in the dream. I think the dream should be, at least, that the state should not tell a lie. They should have it that people can freely use information they get on Twitter, YouTube, Facebook. Why does the Chinese Dream have to be a dream nobody else can even share? For one individual to express his opinion, that’s the only way. It doesn’t matter if that opinion is smart or stupid, that’s their right. They have to respect and trust their own people. But in China you cannot even mention it. They cannot even give out some kind of schedule that would say, “Hey, I don’t trust you guys, you can’t vote now, but in 10 years or in 20 years I will let you vote.” They would never do that. For 60 years nobody has seen a voting ticket. At least they have to let people know what happened during the Cultural Revolution. During the ’89 massacre in Tiananmen Square. Come on. Let them have a dream. But the dream should belong to the individuals, rather than to the state.

BOLLEN: Do you think the young generation of Chinese artists has been unable to make impactful work because of this information blackout and fear of persecution?

AI: Certainly the state behaving in a very controlled manner toward thinking and essential feelings has hurt a generation’s will power. They don’t have the courage, they don’t have imaginations. They’re not poetic, they’re just not strong. They are lacking in so many senses. Some can do a very skillful copying of Western art, but it’s nothing really original.

BOLLEN: You rely on a sort of factory-style approach to production. You have assistants and off-site studios for fabrication. Was this something that you developed from schools of craftwork or more from the Warhol Factory approach to art making?

they said, ‘Weiwei, we can always arrest you again, and we don’t ever have to release you. Just remember that.’ Ai WeiweI

AI: Warhol liberates in two senses. He really liked hard work. He once heard that Picasso produced something like 4,000 works in his lifetime, and Warhol said, “Okay, that’s what our factory can do in a day.” Then he realized, “Oh, I made a mistake. It will take us half a month, not a day.” [laughs] Warhol is funny in this sense. When he’s talking about art, he’s talking about a lifestyle, an attitude, the people around him. You see that, even with the recordings or the film-test shots, all of it. It’s not necessarily a beautiful product, but he himself is the Factory, the whole atmosphere. Warhol is about selling atmospheres. Once he said, “New York restaurants are about selling atmospheres.” So, Warhol created this kind of mythology. I think that’s very important because only through that can other people be a part of it and share in it. That’s why he’s become legendary, because so many people feel they are a part of it. I think my work took that influence from him. It’s always nice to share your energy with young people, the people who might not have any skills but are simply willing to be a part of it. To contribute. Or most of the time not really to contribute, but to make a mess of it. [laughs]

BOLLEN: It reminds me of the party you threw when the Chinese government decided to demolish your new $1 million art studio in Shanghai as punishment. After you announced the crab party, the government put you under house arrest, but that didn’t stop hundreds of attendees showing up in your name and carrying on the festivities. That’s social protest to me, even without you there to lead it. It’s the same with your Twitter feed. You are forced to remain in China, but you find a way to send your message out.

AI: Yeah, I thought that Warhol, if he were living today, would be so rewarded, because he was always sharing, he was so generous.

BOLLEN: What’s your tweet schedule like throughout the day?

AI: I used to tweet, like, eight hours a day or more. Now I restrict myself to maybe three hours a day, just to say hello to old friends, you know, just a few words, make somebody happy the whole day. It’s all about the communication. If we talk to individuals, what makes individuals? Individual; that means he has his own special way to communicate, which creates the form of him. In the information age, this expression and communication has become so different. And that’s what Warhol tried to do. He did it so successfully in the ’70s.

BOLLEN: It’s the individual that often is the centerpiece of your work. For instance, you compiled a list of the names of the schoolchildren killed in the 2008 earthquake, which the Chinese government refused to release. It’s a census of the dead, but you gave each one of the death toll an individual name.

AI: We worked on that for the people who lost the chance to continue their life, and also to work with the people who respect life and refuse to forget.

BOLLEN: In Venice, during the Biennale, you are showing dioramas of your 81 days in prison in 2011. Can you talk about what your imprisonment was like?

AI: I was in the most restricted prison in China, the most tough. The design of the prison is modeled for internal crimes of the Communist party, so it’s like a mafia family’s law. It’s independent to the law this nation openly applies. It’s the place they take you before they give you over to the judicial system. You stay there for a year or two and they make you really suffer to confess everything. It’s a special jail or like some kind of medical center. It’s a strange situation because you’re in solitude, but at the same time, you’re very restricted. It’s like you’re sealed into an iron can with no sense of connection from the outside world or your previous life.

BOLLEN: You were alone in a cell by yourself?

AI: Yes, by myself, but 24 hours with two guards 80 centimeters away looking at you all the time.

BOLLEN: Did they even let you speak to a lawyer?

AI: No. When I was detained at the airport, they put this black hood over my head and removed me to this secret jail. The first thing I did when they removed the hood was ask for a lawyer, just like in the American movies. I said, “Can I talk to a lawyer?” They said no. I said, “Can I call my family?” They said no. And so I asked, “How long will this condition last?” They said, could be half a year or a year. So since then I never asked another question because basically in my mind I was just kidnapped by the state.

BOLLEN: Were you terrified? Or did you try to remain calm in those first days?

AI: I was calm, but angry of course. But at the same time it felt ridiculous because I feel I should always act in the open. I never have a secret. I put everything on Twitter or my blog. My activities have always been open—open discussions, open communications. So I don’t understand why they have to do just the opposite of that. What’s the secrecy for? So I was mixed with anger and excitement, because it puts them in a very bad position by doing that. How could they do that? I still can’t find a logical answer for it.

BOLLEN: Did there ever come a point, say on day 70, when you just submitted to this being a permanent situation? Was there ever some acceptance in your mind that you might be here for good, like writer Liu Xiaobo?

AI: After two months, they gradually started talking about what kind of sentencing they were going to give me. They started to tell me I probably will spend about 10 to 13 years in jail because of subversion of state power, which is a big crime.

BOLLEN: I can’t imagine a point of acceptance in hearing that possible prison sentence.

AI: I was quite desperate. You feel completely vulnerable. You lose sleep. You are very alert at all times, because when you sleep, two guards are also standing next to you, watching you like this. [leans in close]

BOLLEN: So you never were even alone.

AI: No. When you are taking showers, they are standing next to you. Whatever you are doing. They have to be 80 centimeters away, to grab you at any time. So it’s that kind of intimidation and harassment.

BOLLEN: What are the psychological repercussions of that experience? Do you live in fear that you could be taken away again and shelved in that cell indefinitely?

AI: I woke up very early this morning, actually, because I suddenly felt I should make arrangements because, if that happened, I would feel regret that I didn’t arrange this or that.

BOLLEN: So you’re constantly working and thinking of arrangements for a worst-case scenario?

AI: Yeah. All the time I have to think about that. I cannot be stupid and tell myself this will not happen again. Because they never told me why. I asked them when they released me, “You never told me why you arrested me, and you never clearly told me why you are releasing me.” They thought over these two sentences and they said, “Weiwei, we can always arrest you again, and we don’t ever have to release you. Just remember that.”

BOLLEN: Well, if that doesn’t keep you silent …

AI: Yeah. I have to take those words seriously. How can you not take those words seriously? Many people I know—writers, poets—they have all been sentenced not once but sometimes three times after they come out. They serve five or six years, come out another time, and then nine years. Come out again, 12 years. Only because they have a different opinion. They are innocent people, they have beautiful minds, beautiful hearts. This state never hesitated to sacrifice people like this. But they are always trying to hurt the vulnerable, innocent people, to teach other people to behave. So I have to believe this could happen.

BOLLEN: What’s curious about your case, is that not just in China but with any repressive regime, it’s not usually the visual artists who are imprisoned. It’s the writers, the poets, the journalists, the teachers. Visual artists are rarely considered a prime threat because, so often, their visual works can be appropriated by the ruling power and drained of their dissent. Visual art can so easily be turned against itself. But you are an exception.

AI: I’m a visual artist. I always admire those writers. My father was a writer, a poet. I always admire people who can clearly state their mind. Warhol influenced me because of his writing. If I had never read his writings and interviews, I would never have understood his work. Those works are special to me because they state his mind so clearly. So I’m not a writer, but today I think you have to be everything. As an artist you have an obligation to let people know what is on your mind and why you’re doing this.

BOLLEN: The one hundred million hand-painted sunflower seeds you exhibited on the floor for the Tate Modern had a fantastic sense of inclusion. It wasn’t a work programmed for art-world insiders. And yet it seemed to be pointedly issuing from your own perspective and background.

AI: I think of art as coming from daily life, daily experience. I think it’s very important not to have it become work for some kind of elite circle. I’m always interested in people who are not orientated in art circles to become part of it.

BOLLEN: The new market frontier for art seems to be China. Western galleries and auction houses are now competing to open satellites here to extend art commerce to the new financial superpower. How do you feel about that? I’m confused about opening profit-oriented art markets in a country that suppresses the expression of its own artists.

AI: All the auction houses care about is the selling of luxury goods. Of course, most luxury goods in China are for corrupted officials and their relatives. And that made China become the biggest luxury-goods market. In this kind of dictatorship, in this kind of totalitarian society, it is easy to make deals that you cannot make in a democratic society. Come on. You can easily make deals here because it is about private profit. And who profits? Nobody knows. Everything’s a secret. This is a kind of business model that the West is learning from China. You see many Westerners there who shamelessly, I would say, turn their back on the kind of values which generations of thinkers struggled to fight for, for freedom and democracy, just to make a quick profit, to cash in. It’s really pitiful. But that’s our world. We have to accept it.

BOLLEN: It’s strange to have this rise of a market in China obsessed with Western commodities without importing any attendant values of freedom or democracy. Of course, maybe those commodities don’t have anything to do with freedom or democracy in the first place; they just look like they do.

AI: It will take China to destroy the idea of the American Dream. It took a Chinese Dream to make a so-called American Dream become true. You see people start to buy it. They don’t buy one home but maybe 20 of them. They don’t buy just a beach house but the whole street. You can’t even name all of the beautiful cars, but they buy 12 of them just for their daughter’s wedding celebration. Material life can provide them liberty or freedom or just some kind of desperate ignorance or stupidity or a stage to show that. It completely destroys or, at least, delays the honest life. It only shows if you’re dirtier, more shameless, more cheeky. You play this kind of game where you gain—I don’t know what they gain.

BOLLEN: I was thinking back to some of the early works that you produced when you returned to China. For instance, the series of photographs where you dropped and shattered an antique Han Dynasty urn on the floor [Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, 1995/2009]. It’s funny because I recently heard someone expounding on that series as an illustration of planned obsolescence. That antique Han urns weren’t meant to last eternally but were more like Mac computers in that there was a built-in seed of their own demise. I thought, Ai Weiwei couldn’t have been thinking of Mac computers in 1995. But that’s the beauty of such work—it takes on new cultural meanings as it moves in time.

AI: I did that piece truly as a joke. I had three cameras that I brought back to China. And the camera could take, like, five frames every second. And, like most things, I did it quick, no plan. People think everything’s planned, but it was spontaneous. We dropped one and we didn’t get it because the photographer was paying too much attention to this valuable vase. So we had to do another one. We had two of them. [laughs] Then I forgot about those photos for a while. At that time, there were no galleries, no art. I never thought I would become an artist again, you know? I started collecting old Chinese cultural relics, like jade, bronze, beautiful things. I was a top expert on Chinese antiques. Few people had my skill. That’s what I did in the ’90s. On my résumé, I don’t have a show for more than 10 years. I don’t really have any work. I did my first art show after returning to China only in 2003, in Switzerland. But now those photos have become, like, iconic in a sense. But it’s kind of kitsch, huh?

BOLLEN: I like it. But I guess that’s a no on that work being a commentary on the planned obsolescence of designer products.

AI: The author himself may not necessarily know what the work reflects. I remember my father once said, “The silkworm, when it produces the silk, never thinks it will produce the Silk Road.”

BOLLEN: In the West we see Ai Weiwei as a hero of free expression. I wonder, how do the young in China respond to you? Do you feel their interest and excitement about you and your work?

AI: Oh, yeah. They are so influenced I cannot even believe it. The younger ones, they see me as some kind of miracle for still being alive. I feel very happy about that. I want to tell them that they are no different than me. What I did, they can all do. I have a different kind of opportunity now, maybe, but I think today is about sharing those things, those opportunities.

BOLLEN: Like with Warhol, do young people turn up at your studio wanting to hang out?

AI: It’s very strange. They try to come, they send letters, send gifts, they wave at me in the park. Somebody sat in the back of a trailer truck for one month and I didn’t realize he had a candle lit next to him. He said, “Every night I just wait when you come out to see that you’re a real person.” But it’s about them finding a way to build up their own story. It’s not me. I’m just maybe the first sentence they need.

BOLLEN: And that sentence might be found on your Twitter account. In English, 140 characters doesn’t give us a lot of room to express a thought in depth. But you once said that in Chinese, you can write a novella in 140 characters. Perhaps Twitter is most suited to the Chinese language after all.

AI: Yeah, you can put so much in the volume of Chinese words because the structure is so symbolic and dense with meaning. You can write a long story. It’s perfect.

BOLLEN: And the government makes constant attempts to shut down your feed.

AI: They try to take it away every day. But we always move it around.

BOLLEN: Technology has become a form of liberation.

AI: Technology is a liberation. I think the information age probably is the best thing to happen to the human race in human evolution. Now you have the equal opportunity to equip yourself through information and knowledge and express yourself as an independent mind. It’s stronger than any magical thing that can happen to the human race. Especially as a society, people start to judge and adjust their positions. And it still continues to make a big change on the human race, on individuals and on society.

BOLLEN: And yet, perhaps, without technology, you may never have been arrested and sent to prison. And, perhaps, without it, your art might not have been able to expand all over the globe.

AI: And, I thought, I would never be interviewed by Interview magazine.

CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN IS EDITOR AT LARGE FOR INTERVIEW.