Willie Nelson is Still On the Road

“The day I got in [the air force], I started trying to get out. I didn’t like taking orders that much, and I didn’t like getting up at dawn and marching and all that horseshit. I didn’t make a very good soldier, I’m afraid.” – WILLIE NELSON

“The first six decades of my life had been filled with drama,” Willie Nelson writes, with staggering, knee-buckling understatement, toward the end of his new memoir, It’s a Long Story (Little, Brown). Fifty-odd studio albums, more than a dozen film and TV roles, four wives, eight children, more awards and scrapes with the law than anyone can count—yeah, the first 60 years of Nelson’s life are to drama as the Pacific is to water. Deep with it.

But looking back, from his self-sustaining, solar-powered home in Maui, where he has lived for 30-some years, only soothes him for so long. “I just wanted to kick back, enjoy a smoke, and listen to the waves splash against the shore,” he writes. “But beautiful as it was, I couldn’t sit there for long. Something started calling to me. It was that same ‘something’ that had always been calling.”

Cue the guitar licks: “And of course it led where it always led: Back out on the road.”

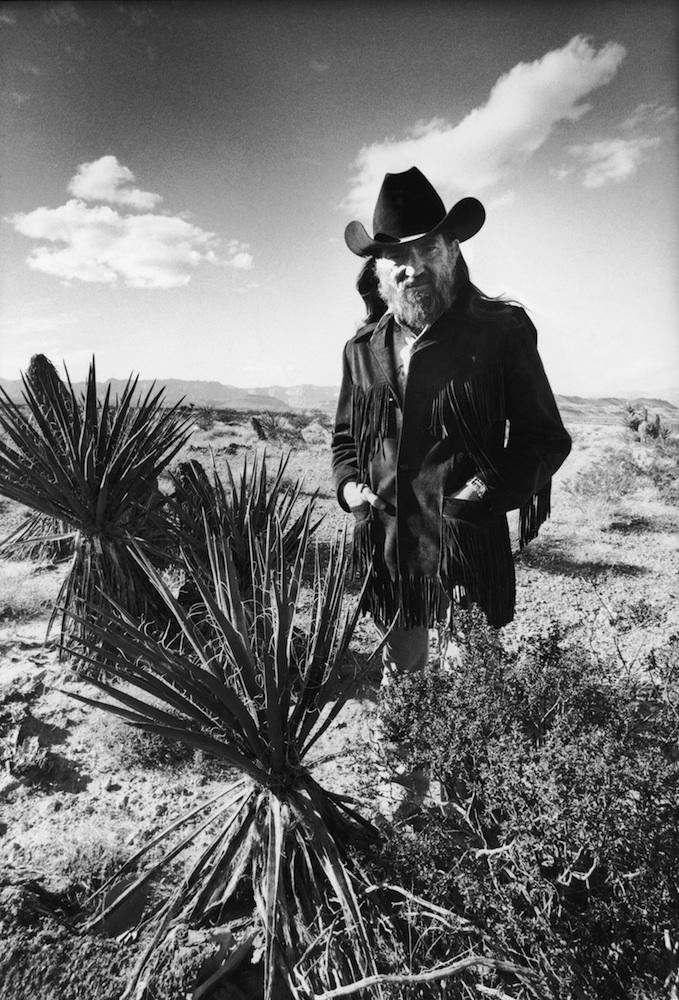

At 82, Nelson (who wrote the song “On the Road Again,” among a thousand or more others) is the elder statesman of country music, a steadying and powerful voice in the industry and on environmental issues, and he’s still on the road much of the year. The music keeps calling.

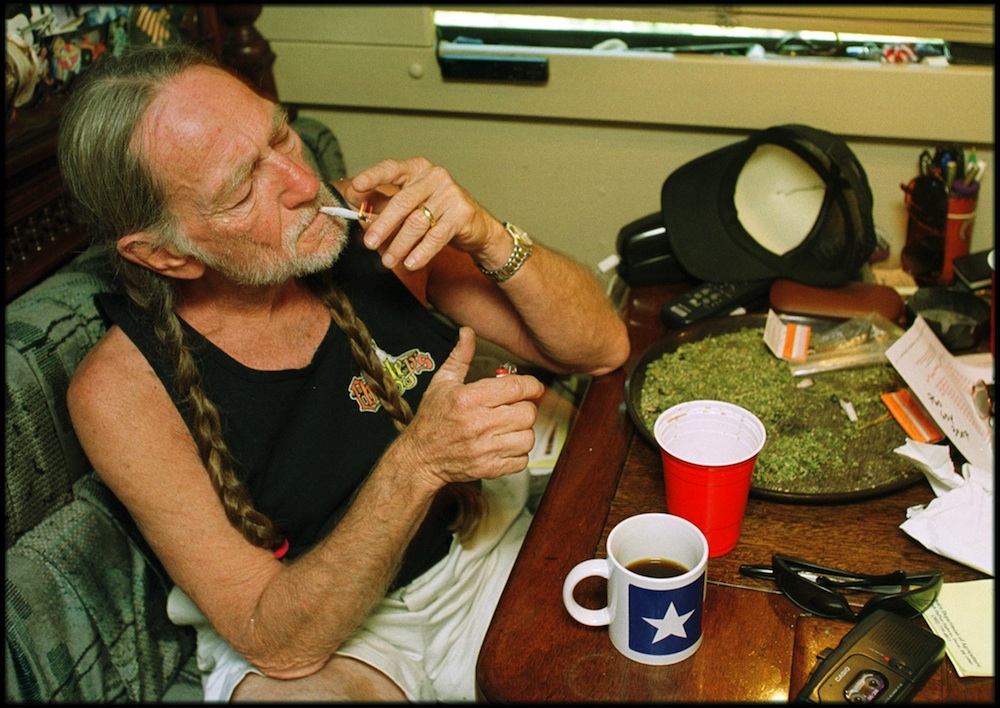

In his unceasing, compulsive rambling about the country, the Depression-era baby and inveterate hustler from Abbott, Texas, has run with the best of ’em, smoked, jammed, and thrown bones with the rest of ’em. Over the course of his more than a hundred albums and 30 years of playing the Farm Aid concert, a benefit he created in support of family farmers, Nelson has played with everyone from Wynton Marsalis to Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash to Waylon Jennings. He’s appeared onscreen numerous times, including in the movies The Electric Horseman (1979), Honeysuckle Rose (1980), and Red Headed Stranger (1986), and on TV shows, including Monk and The Simpsons. At the poker or domino table, he has lifted a small fortune off his Maui neighbors and best buds Woody Harrelson and Owen Wilson—all the while burning more grass than the plains states in a drought. (And yet he has the kind of snap-trap memory and continual, thrumming, joke-telling patter of a sage.)

In the process, Nelson has become an enduring figurehead—the outlaw rider; the hippie-redneck activist; the legalization advocate; the ruffian, poet beatnik—and an endlessly beguiling, elusive man. Willie Nelson is already a legend, and still he rambles on.

As he tells his pal and fellow fan of the pipe, Woody Harrelson, it’s been quite a ride. –Chris Wallace

WOODY HARRELSON: Willieeee, I miss you, brother! Where are you?

WILLIE NELSON: I’m in Biloxi, Mississippi.

HARRELSON: Biloxi, whoa. I’m in London, so we’re close. [laughs] When are you going back to Maui?

NELSON: Around Easter. Will you be there?

HARRELSON: That depends. When is Easter?

NELSON: First week in April, I think.

HARRELSON: Oh, I’ll be there. I’m going to be there for three months. I’m trying to get some time off.

NELSON: Heck yeah, we’ll play some poker, dominoes.

HARRELSON: I got a lot to win back.

NELSON: You win a few thousand every day, and it won’t take you long. [both laugh]

HARRELSON: People know you as an affable, great guy who started Farm Aid. Most people wish you were president, and they don’t realize that you’re a fucking hustler. [both laugh]

NELSON: Don’t tell them about that.

HARRELSON: I’m proud of building the Woody wing on your house there in Maui.

NELSON: Hey, thank you, man. Owen [Wilson] was just there. He contributed a little bit.

HARRELSON: Before we start, do you have, like, a jay sitting around? Or maybe a Volcano or the pen, some kind of vaporizer or anything going on there? Maybe we can get stoned together.

NELSON: I’ve got at least four of each of those things. [both laugh]

HARRELSON: I don’t even know why I asked that.

NELSON: Yeah, really.

HARRELSON: Okay. So tell me about your grandparents, because they were a huge influence on you.

NELSON: My parents divorced when I was about 6 months old, and my grandparents raised me and my sister, Bobbie. I think they did a good job. They spoiled the hell out of us, but that’s what we needed.

HARRELSON: Why did you go to the grandparents? Neither parent could take you?

NELSON: They went different directions, and neither one of them had a way to take care of us. Really they did us a favor just by leaving us with our grandparents.

HARRELSON: This was around the Depression?

NELSON: Yeah, I was born in 1933.

HARRELSON: Do you have any memories of the Depression?

NELSON: I didn’t think we were any worse off than all of the other folks around us. Everybody I knew had to work in the fields, pick cotton, pull corn, bale hay; that’s the way we paid our way through school and bought our school supplies and things. My granddaddy died when I was about 6 years old, I think. And my grandmother took a job cooking in the school lunchroom. So she did great. She made $18 a week.

HARRELSON: That must’ve seemed like a small fortune.

NELSON: Well, it was. It took care of us.

HARRELSON: You really have a fond kind of vibe for your grandmother.

NELSON: And my granddad, too. He was a blacksmith, and I hung out in the blacksmith shop with him when I was a kid, watching him shoe horses. In fact, he got kicked by a horse one time, and he had to wear one of those rupture belts all the rest of his life. They were hard workers.

HARRELSON: Was he a disciplinarian?

NELSON: Well, he spanked me one time. I had to be 4, 5 years old, and I ran away from home. They brought me back and he whipped my little butt. He had one of those razor strops. You know, one of those wide, leather razor strops that you sharpen your razor on. And he hit me a few times with that. It sounded real terrible, but it didn’t hurt that much.

HARRELSON: But I’m sure you made a lot of crying noises so he’d stop.

NELSON: Oh, yeah. I screamed. [both laugh]

HARRELSON: You had that actor in you back then, didn’t you?

NELSON: Hustle! I had that hustle.

HARRELSON: When did you get your first guitar?

NELSON: I was about 5 or 6 years old, and I bought this guitar out of a Sears, Roebuck catalog. I think it was a Harmony guitar. My sister played the piano. She’s two years older than me, and I always wanted to play something. So my grandmother got the guitar for me, and showed me a couple of chords to start off. And then I got me a book. Next thing you know, I was playing along with sister.

HARRELSON: So when you graduated high school, around 1950, you joined the Air Force. What was that like?

NELSON: I didn’t care for it at all. The day I got in, I started trying to get out. I didn’t like taking orders that much, and I didn’t like getting up at dawn and marching and all that horseshit. I didn’t make a very good soldier, I’m afraid.

HARRELSON: I can’t imagine you taking orders.

NELSON: No.

HARRELSON: I mean, except from Annie [Nelson, Willie’s wife], obviously. [both laugh] So you weren’t a part of the Korean War?

NELSON: I never did go overseas. I spent all my time in Biloxi, Mississippi, right here where I’m at now. I took basic training down in San Antonio, at Lackland Air Force Base, and in Wichita Falls, at Sheppard Air Force Base. Then I spent my last few months in the Air Force here. I come back here to Biloxi quite a bit. I like it here.

HARRELSON: So out of the Air Force, you went to Baylor University?

NELSON: Yeah, I had some G.I. Bill coming. So I took what I had and went to Baylor there for a while, majored in dominoes. [both laugh]

HARRELSON: That’s what I want to know. When did you become a hustler?

NELSON: I’ve been playing dominoes all my life. When I was really young, the old men in Abbott all played dominoes. And when one of them would have to get up and go somewhere, they’d get me to come sit in. If I’d make a mistake, they’d yell at me and throw shit at me. So I learned to play dominoes pretty good. And some friends of mine, like old Zeke Varnon up in Hillsboro, who is the best dominoes player I ever met, showed me a lot of stuff. He was a card hustler, dominoes, pool … You name it, Zeke was good at it.

HARRELSON: I guess those are the people I have to thank for all the—what do you call it?—remuneration I’ve thrown your direction.

NELSON: I think remuneration is the word for it, yeah. [both laugh]

HARRELSON: Oh, man. I’ve experienced more pain in your house than I think anywhere.

NELSON: But you take it well, Woody. That’s what I tell them all.

HARRELSON: You notice how there’s just no shift from when I’m winning or losing—I just don’t care. I’m happy. So were you an encyclopedia salesman?

NELSON: I sold encyclopedias door-to-door. I also sold Singer sewing machines.

HARRELSON: Did you do well with that? Because I’m imagining Willie Nelson coming to my door to sell me something, whatever it is, I’m going to buy it.

NELSON: The big deal was to get in the door. When I would sell encyclopedias, I would drive down the road looking for a house with a swing set in the back, and I’d say, “Oh, those folks got kids. They need some books.” I’d knock on their door and sell them a set of encyclopedias, and those books were from $300 to $600. I’d look around the house, and if there wasn’t that much furniture in the house, I felt a little bad about selling a $600 set of books to people who couldn’t afford a couch. So I didn’t last at that job very long.

HARRELSON: The overly compassionate salesman. You just weren’t meant to do that, I think. How did you end up in Nashville?

NELSON: Well, when I was growing up, Nashville was the place to go if you had songs to sell and thought you had talent and wanted to tour and be on Grand Ole Opry [radio show]. It was the big deal back in those days to play the Grand Ole Opry. And you could travel around the world saying, “Hi, I’m Willie from the Grand Ole Opry.” And back in those days, it really helped you book dates. I had to quit the Opry because they insisted that you play it 26 weeks out of the year. They still do, I guess. But I was playing in Texas a lot, so it was hard on me to get back 26 weeks out of the year. I’ll always regret it.

HARRELSON: You were just driving back and forth?

NELSON: Yeah, and my good days were Friday and Saturday, so it was really cutting into my income to have to go all the way back to Nashville to play the Opry, and I was kind of torn between the two.

HARRELSON: But at the time, most anybody would have been frickin’ thrilled to be playing the Opry.

NELSON: Oh, yeah.

HARRELSON: I’ve got to backtrack. When did you say, “This is what I’m going to do”?

NELSON: I always knew that I wanted to do this. My first job was in a Bohemian polka band, the Rejcek family polka band in Abbott. The old man in the band had another blacksmith shop in Abbott, but he liked me. All he had was horns and drums, and I was set up over there with my little guitar with no amps or nothing. I would play as loud as I wanted to, and nobody could hear me. He paid me $8 or $10. I had been working in the fields all day for $2, baling hay, so that was a lot of money for me. He took good care of me. He had 20 children, I think, and they were all musicians.

HARRELSON: 20 kids, and I’m guessing different wives?

NELSON: Well now, that I can’t tell you for sure.

HARRELSON: I mean, you’ve got, like, 27 children and how many wives? Is it too early for that question?

NELSON: I don’t know how people handle 20 kids. I got a few, who I love dearly, but 20? Maybe if I went around the world, I’d have 20. [both laugh]

HARRELSON: You got at least 20 out there you don’t even know about.

NELSON: Lord willing! [both laugh]

HARRELSON: But officially, you have how many?

NELSON: Officially, we have Lana, who’s standing right here by me, my oldest, and her sister, Susie, and I had a son named Billy. He passed away. And Paula and Amy, from me and Connie. And Lukas and Micah, from me and Annie. I got a bunch of good kids.

HARRELSON: That’s a goodly number though. I lost track of how many that was …

NELSON: The boys are playing in the band with me tonight. Micah’s a great drummer, and Luke plays great guitar and sings, and they’re really helping us out on this tour.

HARRELSON: So tell me about this fellow Hank Cochran. He had a major influence on your life.

I know there’s a lot of hustlers out there, in every walk of life. Whether they’re preachers or insurance salesmen, it’s about the same thing. WILLIE NELSON

NELSON: Hank Cochran was a songwriter in Nashville, and he wrote for Pamper Music. Hank got me a job there at Pamper Music writing songs [in the early 1960s], with a $50 a week salary. So that set me up in Nashville. And then Ray Price, who owned Pamper Music, heard that I was a musician. And he called and asked me if I could play bass. His bass player, Donny Young, had quit on him, I think out in Nebraska somewhere. I said, “Sure, can’t everybody?” But I had never played bass a day in my life. So on my way to the first gig, Jimmy Day taught me how to play bass. Several years later I asked Ray if he knew I couldn’t play bass, and he said, “Yeah.” [both laugh] I didn’t fool him.

HARRELSON: At this time, you wrote a hell of a lot of amazing songs: “Night Life,” “Funny How Time Slips Away,” “Crazy,” “Hello Walls,” “Wake Me When It’s Over.” Great songs that other people were performing, like Roy Orbison with “Pretty Paper.” I know you had to be glad to get a paycheck and have other people singing your songs, but were you frustrated at the same time?

NELSON: Not in the least. I knew what I could do, and I was getting my songs recorded. I was making money. I had no reason to complain about anything. I was touring with Ray Price, and whenever we would get home, we’d go into the studio and put down all these songs that me and Hank had written. The publishing company would give us three hours, and we’d see how many songs we could put down—we’d put down 20 or 30 songs in three hours.

HARRELSON: That’s outrageous!

NELSON: But I was performing. I was working Texas a lot, playing all of the beer joints down there, making a pretty good living. And, in fact, when I left Nashville, I went back to Texas and said, “Hey, I can make a living in Texas working the Broken Spoke and different places like that.”

HARRELSON: So that was all initiated when your house burned down in 1970? Was that kind of a blessing in disguise?

NELSON: Yeah, it really was. We were all living up there in Ridgetop, Tennessee, and writing songs and raising hogs. [both laugh] I decided I wanted to be a hog farmer, and I bought 17 weaner pigs. I think I paid 27 cents a pound for ’em. Brought ’em home and fed ’em for five months, sold ’em for 17 cents a pound. I lost a small fortune raising fuckin’ hogs. But I learned a lot. I learned I’d much rather be in Texas playing the beer joints. [both laugh]

HARRELSON: So when you got to Texas, you were already a known entity?

NELSON: More or less, yeah.

HARRELSON: So then everything started to really shift for you. You made Shotgun Willie [1973]. You made, like, three albums in succession.

NELSON: Red Headed Stranger [1975]—that was one of the first ones that started doing well. It had “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain.” My plan was to have the album come out the same time I had the movie come out. But you know how that goes—it took a decade before [the movie Red Headed Stranger] got made.

HARRELSON: Now, hold it. Was Red Headed Stranger the album that you just heard running through your head when you were driving through the night?

NELSON: Yeah. I was coming back through Denver, driving to Austin. The lights were really bright, so, you know, “The bright lights of Denver / Were shining like diamonds / Like 10,000 stars in the sky.” And, “Nobody cared who you were or where you come from / You were judged by the look in your eye.” So I kind of set the theme for the Red Headed Stranger. I had it pretty much written by the time we got home. It didn’t take that long. But then “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” was already written. Some of those songs had been hits in the past, and I placed them in there because they fit the story.

HARRELSON: So by the time that album came out, your star had really ascended?

NELSON: Yeah, pretty good. And I got lucky.

HARRELSON: You still tour over 100 days a year, I think. Were you on that kind of pace already?

NELSON: Yeah. I’m trying to cut back. We’re playing a little less than we have been. I think we’ll all be able to stay out here longer if we do it that way.

HARRELSON: And it’s helping all your friends out, too, because then we get to hang with you more. And how could you possibly make more out on the road than you do right at home? [both laugh] So tell me how you met Annie, your wife.

NELSON: I was doing a movie, Stagecoach [1986], a remake of the old John Wayne classic. We were in Tucson, and Annie was doing the makeup on the movie. We were there together for several weeks.

HARRELSON: And how did it go from makeup artist to … home stylist? [both laugh]

NELSON: Well, she still does my hair.

HARRELSON: How’d you get into biodiesel?

NELSON: Well, just as an alternative to using a lot of oil. A lot of the truckers use it. We use it on our buses. I noticed the price of oil has come down a lot, so that makes it more competitive. You know, if a guy can fill up with regular gas rather than pay a little bit more for some biofuels, he might do that. We got a factory there in Hillsboro, where we go around picking up all the vegetable oil from the restaurants and turning it into biofuel. My old buddy Bob King in Maui, at Pacific Biodiesel, he kind of helped start the whole idea. He’s doing fine. You remember him, don’t you?

HARRELSON: Oh, yeah. I go there and fill up every time I need to fuel. The UN calls 2015 the International Year of Soils, and I know you’re really involved in helping farmers. How’s that going?

NELSON: From what I hear, the ones who have gone into organic farming are doing very well. A lot of people are realizing that it’s better for them to buy from a local farmer. Instead of having their breakfast come from 1,500 miles away, they can get the same bacon and eggs from the farmer a mile out in the country. So I see some progress. We’re doing another Farm Aid this year, on September 19. I think this makes almost 30 of them.

HARRELSON: Wow. I didn’t realize it was that many. That is a cool thing and a great event, but I’m sure you look forward to the day when you don’t have to do it.

NELSON: You would think that our real intelligent people there in Washington would see the problem and fix it immediately, but unfortunately, the big corporations have pretty much told them what to do. And big corporations like it the way it is, all the pesticides and chemicals that they put on the land. It doesn’t change, and I think you have to expect that from people. You have to judge other people against yourself. They say you’re not supposed to do that, but that’s the only way I can judge other people. I kind of compare them to myself. And I know there’s a lot of hustlers out there, in every walk of life. Whether they’re preachers or insurance salesmen, it’s about the same thing.

HARRELSON: I’ve stopped hoping for much from the politicians.

NELSON: Yeah, they’re all bought and paid for.

HARRELSON: But this is boring …

NELSON: Let’s talk about sex.

HARRELSON: Yeah. How old were you when you first started masturbating?

NELSON: Um, let me see. [both laugh] I remember the first time I had sex. I’ll never forget what she said. “Moooooo!”

HARRELSON: That is honorable. And very funny.

NELSON: Do you want to hear a good joke?

HARRELSON: Yes, I do.

NELSON: These people were in a courtroom, and they were accusing this guy of having sex with an animal. And so this lady said, “I only know what I saw. I was driving down the road, and I saw this guy out there with this sheep, and they were making love. And you’re not going to believe this, your Honor, but when they got through, the little sheep laid its head over on the guy’s shoulder and went to sleep.” And one of the guys on the jury punched another one in his elbow and said, “Yeah, it’ll do that.” [both laugh]

HARRELSON: I tell your jokes all the time—but when it gets met with a weird response, I always give you credit—the one about two nuns riding their bikes around the Vatican?

NELSON: And one says to the other, “I’ve never come this way before.” And the other one says, “Me neither, must be the cobblestones.” [both laugh]

HARRELSON: You probably have 52,000 jokes in your memory bank.

NELSON: You’re probably close.

HARRELSON: I’ve never seen you run out.

NELSON: I must enjoy telling them. I know I enjoy hearing ’em. And whenever I hear a good one, I kind of try to hang on to it and spread it around.

HARRELSON: Who’s influenced you the most?

NELSON: Well, we have to go all the way back to guys like Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, Floyd Tillman, Leon Payne, Ted Daffan, Spade Cooley, Hank Williams, Django Reinhardt. Me and Merle [Haggard] have a new album coming out called Django and Jimmie, about Django Reinhardt and Jimmie Rodgers. There’s a song that says, “There might not have been a Merle or a Willie without a Django and Jimmie.”

HARRELSON: Ah! And did y’all write together?

NELSON: Merle wrote a few in there. Merle wrote one about Johnny Cash, and he wrote one about us called “The Only One Wilder Than Me.” [both laugh]

HARRELSON: And that’s saying something.

NELSON: And we did a song on there, coming out 4/20, called “It’s All Going to Pot.” “Whether we like it or not / As far as I can tell, the world’s gone to hell / And we’re sure gonna miss it a lot / And all of the whiskey in Lynchburg, Tennessee, just couldn’t hit the spot / So here’s a $100 bill, you can keep your pills, friend / It’s all going to pot.” [both laugh]

HARRELSON: That is great, man! Willie, I got to say, it really blows my mind how you tour over 100 days a year, you come up with at least one or two albums a year, and then you’re also writing books—you have a book coming out, right?

NELSON: Right. It’s called It’s a Long Story. [Harrelson laughs] I reviewed my own book, and I cut a song called “It’s a Long Story” [sings] “It’s a long story, you’ll probably never make it to the end / There’s way too many words, way too many pages / Too much time to stop and start again / But if you love a good mystery, you’ll never find a better one, my friend / It’s a real whodunit, who lost it, and who won it / And who’s still around to lose it all again.”

HARRELSON: Nice, man! You know, I never told you what a big influence you’ve been on my life. I was living in Costa Rica with Laura, and our daughters, Deni and Zoe, and I came back to L.A., and my buddy Jim Brooks asked me if I wanted to go to a concert you were doing. I went, it was a great show, and afterwards, this beautiful woman, Annie, comes up and says, “Hey, I’m Willie’s wife. Why don’t you come back and hang on the bus?” I’m like, “Whoa, sure.” So we go back there, the bus doors open, all the smoke billows out like, you know, Cheech and Chong, and I look through the fog, and I see you in there, with a big old fatty, like, “Come on in. Let’s burn one!” [Nelson laughs] The first of, like, 97,000 joints we would smoke together. And we had the most amazing conversation. I really felt like I met a real soul mate—someone I would always know. Of course, that proved to be true, but one of the great things that happened on that occasion, when we first met, which is an example of your generosity, was you said to me, “I live in Maui. If you ever want to come over there and stay—even if I’m not there—you can do that.” So, of course, we took you up on it, and ended up in Maui. And now, almost 20 years later, I’ve been living in Maui, and it’s thanks to you. So thanks for being such a good influence on my life, bro.

NELSON: Well, you’re sure welcome. I was lucky. I got booked over there, and once I got there, I realized, “Hey, this would be a good place to stay.”

HARRELSON: Yeah, you got a great spot there on the water.

NELSON: One thing I want to run by you, you know our spot over there on the ocean, what do you think about us putting in a little floatin’ gambling casino out there, maybe a little houseboat, you know, and calling it Woody and Willie’s?

HARRELSON: I love that idea. Bring ’em up in a boat, get a little gambling done, and send ’em back home.

NELSON: Yeah, they can ski over or whatever.

HARRELSON: You’ll have Owen there every night, trying to win back what he lost the previous night. I love that idea. I’m in.

NELSON: I’ll see you in Maui!

WOODY HARRELSON IS AN EMMY AWARD-WINNING ACTOR WHOSE FILMS INCLUDE NATURAL BORN KILLERS, THE PEOPLE VS. LARRY FLYNT, AND NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN, AND TV SHOWS INCLUDE CHEERS AND HBO’S TRUE DETECTIVE.