New Again: D’Angelo

In New Again, we highlight a piece from Interview’s past that resonates with the present.

Ladies of New York City, prepare to swoon—D’Angelo is back. Actually back. According to the below interview with Veronica Webb from 1996, though, he never left. “If I ever come to a point where I decide to stop doing videos and performing or whatever,” he said, “if it ever comes to that point, that don’t mean I’ve stopped doing music.” There won’t be any funny business at his show in Williamsburg Park tomorrow, which will be his largest show in New York since he reemerged on the music scene. With rumors of new album in the works, D’Angelo is doing the festival circuit to remind fans that he and his angelic, soulful voice haven’t gone anywhere. His debut album Brown Sugar [1995], prompted complimentary comparisons to Prince, Lenny Kravitz, and Marvin Gaye—who he reveals below is a person that has inexplicably terrified him since childhood. D’Angelo also discusses his desire to only make “black” music, sharing music with his mom, and of course, his “unique” look.

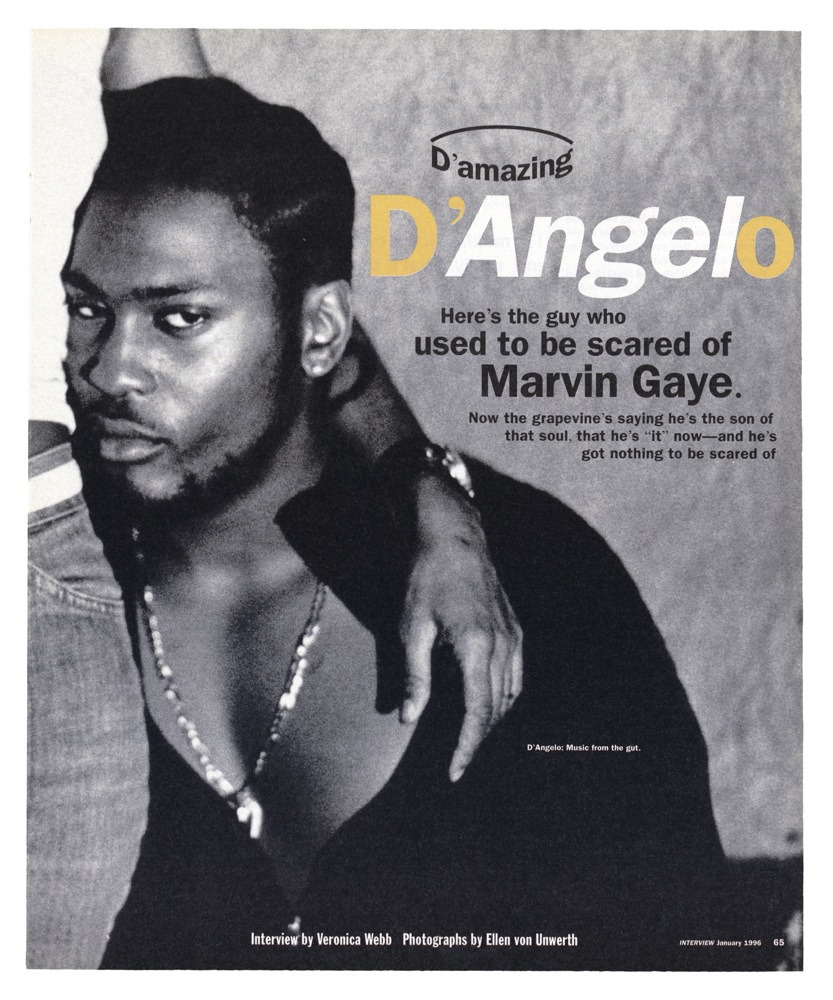

D’Amazing D’Angelo

By Veronica Webb

There is nothing remarkable about D’Angelo’s background, but there is something incredible about his music, which his why it’s become so popular. The son of a preacherman from Virginia, he is one of the common folk who found a sound within himself that is immediately recognizable as belonging to him alone, even before his singing starts. Because of this, he’s escaped comparisons with his peers, leap-frogging, instead, to comparisons with Marvin Gaye, Prince, and Stevie Wonder. Having your own sound and your own visual image means that you’ve created a new category. I don’t know what to call it.

There is something intangible about him, and everybody wants to get a taste of it. The title track from the 21-year-old soul singer’s debut album, Brown Sugar (EMI), has become an official R&B anthem. He swings through all the numbers on the record in a falsetto voice that expresses the orgasmic and the hideous with equally chilling force. The sound of the Fender Rhodes organ he plays comes across with a sweet, gentle clank, haunting you with all your familiar fears and desires, like the ghost of Christmas past. The music is not about macho power, politics, or materialism. It’s about hundreds of little mysterious feelings we can all relate to.

After canceling our initial interview because of a bad case of laryngitis, D’Angelo called me from the road. Here’s what he had to say.

VERONICA WEBB: Hello. Feeling better?

D’ANGELO: Yeah, I’m feeling a little better. How you doing?

WEBB: Well, I got a cold too, so we’re in the same boat. Where are you now?

D’ANGELO: In Boulder, Colorado.

WEBB: So where else you been?

D’ANGELO: Before I started this tour, we did a promotional tour, like Europe and Japan. Then we went smack-dab into this thing.

WEBB: Are the audiences different from, say, a city in Europe to a city like Boulder?

D’ANGELO: A little bit different. In Europe they’re more calm, more reserved, you know what I mean? Here, in the States, people are more wild, a little more open. I guess it takes a lot to impress those people up there in Europe. Especially in London.

WEBB: How did you do in London?

D’ANGELO: We slammed it, you know? We did two shoes at the Jazz Café and we slammed it.

WEBB: So tell me, how did you choose to play a Fender Rhodes [keyboard], because that thing is hard to play. It’s real physical.

D’ANGELO: It’s not too hard to play if you get the right one, with some good action on the keys. If you got an old one that ain’t been touched up, it could be kind of difficult to get real loose on it.

WEBB: Do you have an old one?

D’ANGELO: Yeah. This tech guy put some new stuff inside, so it’s got kind of an old body, but some new parts inside.

WEBB: Old body, new head?

D’ANGELO: Yeah.

WEBB: Kind of like you, you know? [D’Angelo laughs] Because people’ll be calling you the “Son of Soul,” and saying that you got the whole skeleton, the whole structure of soul that had come before, but the way you come at your music, the way you sing, and the way you make your entrances is more informed by hip-hop.

D’ANGELO: Yeah. You’re right.

WEBB: You wrote most of your album, Brown Sugar, between the ages of 18 and 19, right?

D’ANGELO: That’s right, basically during that period. I wrote almost all the songs while I was still in Virginia.

WEBB: And now you’re 21, you blew up, you’ve been around the world, and you’re still doing the same material that you wrote when you were the boy from Virginia. Do you feel a lot different inside? Have you written a lot of other music since then?

D’ANGELO: I’ve been real busy promoting this record, so I haven’t had the time to do a lot of writing. But nothing’s really changed about me. It’s just my day-to-day activities have changed, and as a person, I have to adapt to those changes.

WEBB: Does that take you away from your music, or bring you closer to your music?

D’ANGELO: It depends, really. I’m closest to the music when I’m onstage with the band, playing.

WEBB: I guess why I was asking you that question is because sometimes you go to see a musician like Prince or somebody and they’re up there still playing “Purple Rain” 12 years later. And I’m wondering, you play the same songs for three years…

D’ANGELO: Yeah, but Prince right now, he ain’t playing nothing that he used to. All the songs he made under that name, Prince, he ain’t gonna play ’em no more in his concerts. I know a lot of other people, too, that ain’t doing none of their old material, and are trying to write their new shit. I can relate to that ’cause you just get tired of it. Yeah, I’m still basically new. I mean, in a lot of ways the songs are still old to me because I wrote those songs a while ago, so I lived with ’em a long time, but it’s still fresh ’cause this is my first run. It’s my first time doing something like this.

WEBB: I see you quoted a lot saying that you don’t want to put any limit on what you think R&B is. Like with this first album of yours—it’s not pop, but it’s commercial.

D’ANGELO: Yeah, it is kinda.

WEBB: When I think of people trying to stretch out the limits of R&B, certainly to an extent Prince has done it, and Lenny Kravitz also, but that kind of experimenting can be risky, because you can lose your core audience, which is urban, as theirs was when they started out.

D’ANGELO: It all depends how hard you do it, how you stretch it out. I don’t know if it is stretching a certain margin, or if there’s an outline that you follow. And if there is, you can go into a lot of different aspects of that outline, and many a different avenue, but it’s still the same vein really, and that’s the whole point. Prince is extremely soulful, but he can get real rock-‘n’-rollish. So can Lenny Kravitz. Lenny’s real soulful but he’s got that rock with him, too. On the whole, I guess black folks ain’t trying to handle rock-‘n’-roll, really. But, like I say, it depends on how you do it. If you do it right then I think people will appreciate it for what it is.

WEBB: When you talk about following a certain vein or outline, do you have one for yourself?

D’ANGELO: Yeah. I’m making black music. That’s the only outline for me, really. That’s the only boundary to stay with. It’s soul music. I’m going all out in those terms.

WEBB: And, to you, are there current instruments or certain lyrics or even certain beats in the measure that would change it from black music?

D’ANGELO: Yeah, there are certain things. But I don’t know if it is as simple as pointing your finger at them like that, because it depends on the whole feel of a song. I mean, you can have some real country instruments in a song, like a slide guitar, but if you do them right the soul of the music is black. If you do it right then it sounds like some old blues shit.

WEBB: Right, then it is B.B. King.

D’ANGELO: Exactly.

WEBB: If you do it wrong, it’s Garth Brooks.

D’ANGELO: Yeah, there you go. [laughs] It’s just the way you approach it. That song “I Hate You” by Prince, that’s black to me but it’s got some rock shit in it, too. That whole [sings the chorus]—it’s wacky, but it’s the way he approached it. It’s not a rock-‘n’-roll song.

WEBB: Visually, you’re kind of unique, like the way you dress and everything. I can’t tell if you’re rich or poor. I can’t tell if you’re suburban or urban. I can’t tell if you’re sensitive or if you want to be a mack. It’s like a real old-fashioned distressed kind of elegance.

D’ANGELO: [amused] Mmm-hmmm. O.K.

WEBB: Like when you see pictures of [Duke] Ellington traveling on the train. They were always dressed that way.

D’ANGELO: Yeah. That’s just the way I dress and all that. I mean, I don’t know how I want to come across looking, really. I just look how I am.

WEBB: So for you it’s about the music, it’s not so much about the image.

D’ANGELO: Definitely. The way I look is a reflection of who I am. That’s how my music is too.

WEBB: You know, sometimes people accuse you of not having enough showmanship. You just go out there onstage, sit down, and play.

D’ANGELO: Yeah. Well, the show is coming from the music. I get on the stage with the band, and I communicate with my musicians, and the music that we create and all that is coming out of us. The music is making the show and the music is creating the atmosphere, so if you close your eyes and listen and feel what it is that’s coming out of the speakers, that’s the whole point.

WEBB: But I heard you can really dance. You’re just always behind that Fender.

D’ANGELO: I used to be a good dancer back in the day.

WEBB: [laughs] I heard back in the day that your mom used to go through your music with you.

D’ANGELO: Not really. I mean, I lived in the house with her so she had no choice but to hear what I was doing. [both laugh] And I would ask her for her opinion, you know. I used to like doing that because I would let my friends hear what I did, but they listened to it on another level. My mom listened to it with a different ear, because she’s older.

WEBB: Moms is a huge Marvin Gaye fan, too, right?

D’ANGELO: Oh yeah. Her and my aunt and my stepfather are big Marvin Gaye fans, big Icy Brothers fans, big Earth, Wind and Fire fans, you know.

WEBB: I also read somewhere that you always had visions of fame.

D’ANGELO: That’s true. Since I started playing, really, since I was like three. I imagined myself famous but the vision was blurry, I guess. What you see on TV isn’t a realistic picture.

WEBB: I want to ask you about another side of the picture, which is how you came by musical director Mike Bearden. Was there something about what he did with Madonna that impressed you? Because I was wondering if you said to yourself, “Let me get the person who put Madonna on her way, because that’s the level of success I’m going for.”

D’ANGELO: Not really. A friend of mine who is my sound man also did the sound for Madonna, and he recommended Mike Bearden to me. But, especially when I first came up here to New York, everybody wanted to hook me up with this guy who’s Prince’s [sound] engineer. Almost everybody wanted me to hook up with him and go to L.A. and do all that just because that’s the route Prince took. And for a while I was listening to all of that. “Yeah, if it’s good enough for Prince, it should be good enough for me.” But I mean, that’s not the case, really. Prince is a different person than I am. You just got to find the right person for you, whoever you click with.

WEBB: You know, in Prince’s first song on his self-titled 1992 album, “My Name is Prince,” where he says, “I know from righteous/I know from sin/I got two sides/And they’re both friends/Don’t try to clock ’em/Cuz they’re much too fast—”

D’ANGELO: “If you try to stop ’em, they’ll kick that ass.” Yeah, he’s talking about everybody, I guess. He’s talking about his split personality, like those little voices that are inside each person, really. Almost like the angel and the devil.

WEBB: Now that you’re blowing up, is there an angel on one shoulder and a devil on the other one?

D’ANGELO: Yeah, but it ain’t about, “Now that I’m blowing up.” There was shit available, mass shit available to me before I got involved in this music business. I guess it’s all about how you look at it, and what mind frame you’re in. I still put my pants on one leg at a time.

WEBB: Except now there’s a thousand pairs of pants to choose from.

D’ANGELO: You might think so, but you have to be me to know that.

WEBB: So every artist has to choose their own path.

D’ANGELO: Yeah, they have to choose their own path.

WEBB: Which kind of leads me back to Marvin Gaye. I read that you used to have nightmares about Marvin Gaye as a kid. Did he scare you because you felt like, “I could be consumed by my music. I could be consumed by this life that I’m putting myself into?”

D’ANGELO: I don’t know what scared me about him. I just know that he was scary, and that all of his… his aura was frightening to me. I can’t explain why.

WEBB: Like, even the California Raisins commercial scared you, didn’t it?

D’ANGELO: Well, no, it wasn’t about the California Raisins…

WEBB: [laughs] Admit it. You was scared of the Raisins!

D’ANGELO: [chuckles] Shit, no, not the Raisins. It was the song “I Heard It Through the Grapevine.” It was the music. Even before Marvin Gaye died, before I even really knew who Marvin Gaye was, when I was little, that song used to frighten me. Just the music, and I never knew why. When he came out with “(Sexual) Healing”—I mean I would look at his picture on that album cover, Midnight Love [1982], and just his face, his aura, was scary to me. Have you read the Marvin Gaye biography [Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye]?

WEBB: Yes, I have.

D’ANGELO: That’s a deep book, ain’t it?

WEBB: Mmm-hmmm. And every time I think about that book I realize music is a powerful give that can do a lot of different things to people. So what do you want to build with your music?

D’ANGELO: I just want to start with building the foundation.

WEBB: But do you see yourself as a life-long performer.

D’ANGELO: I don’t know. I mean, I plan to be involved in music—doing music, writing music—for the rest of my life. But I can’t see the future. I don’t know what tomorrow’s gonna bring. To me, music is far more deep than making videos and doing shit like that. Music’s some deep shit, you know what I mean? So, if I ever come to a point where I decide to stop doing videos and performing or whatever, if it ever comes to that point, that don’t mean I’ve stopped doing music. Music is me. That’s what I am, really. So, that’s a part of me till the day I die.

Postscript: After I hung up the phone with D’Angelo, I called my friend Prince and relayed this conversation to him. He asked me to invite D’Angelo to Paisley Park in Minneapolis to do a duet. When I called D’Angelo back a few days later to extend the invitation, it took his breath away. Listen up for the results!

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY RAN IN THE JANUARY 1996 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

New Again runs every Wednesday. For more, click here.