New Again: Bon Jovi

Question: What American rock band has sold at least 100 million records, performed more than 2,700 concerts in over 50 countries, and is releasing its 13th studio album this Friday? Hint: Unforgettable hits include “It’s My Life” and “Livin’ on a Prayer.” Answer: Bon Jovi. It’s been three years since the band’s last album, but now Jon Bon Jovi, David Bryan, and Tico Torres are back with Burning Bridges (Mercury Records), which the frontman refers to as the “fan’s record.”

We’re slightly ambivalent about the release (and apparently people in Vancouver are, too), but regardless, this fall the band will embark on an international tour, stopping everywhere from China to India, Indonesia, South Korea, and the UAE. Since Bon Jovi’s inception in 1983, JBJ himself (born John Francis Bongiovi Jr.) has been given an award from the White House Council for Community Scholars and President Obama, was named the “Sexiest Rock Star” by People Magazine, and received an honorary doctorate in humanities from Monmouth University.

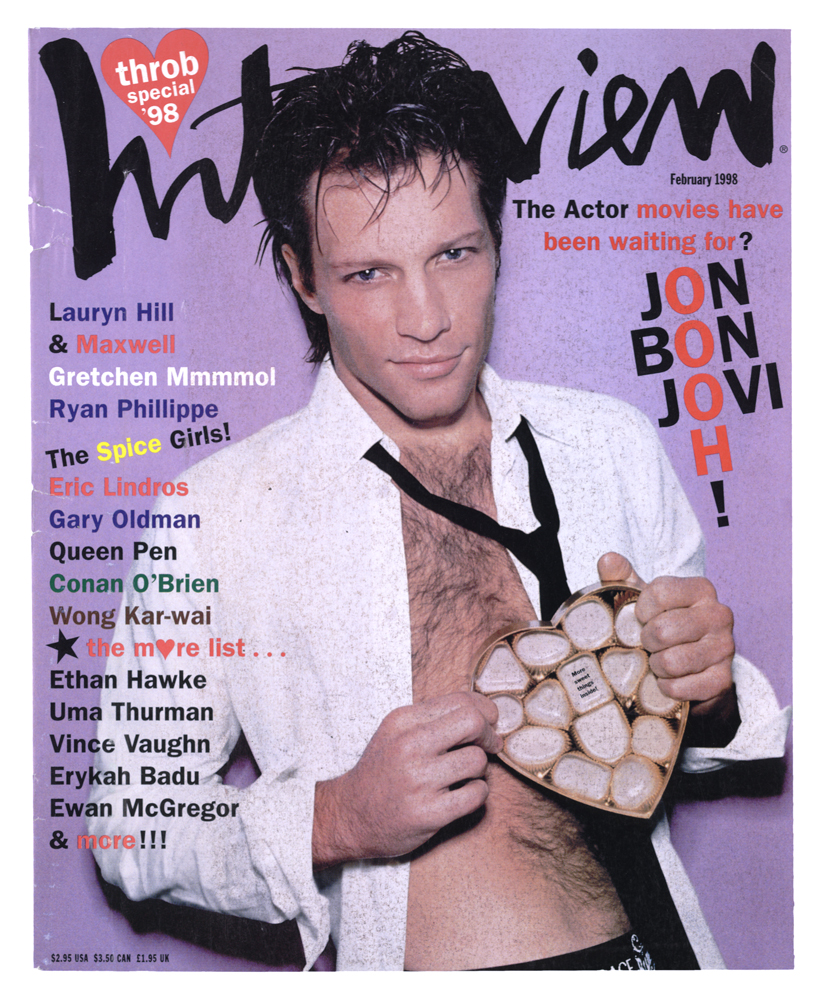

In the 1990s, Bon Jovi even emerged as an actor. During that time, he received at least three features in this magazine, but none as great as his cover from our February 1998 interview. In light of Burning Bridges, here we revisit the cover story, with photos by Ellen von Unwerth and an interview conducted by Ingrid Sischy. —Saloni Gajjar

Jon Bon Jovi

By Ingrid Sischy

He’s a real-life Rocky, the one who stands in the shadow of more obvious champs but ends up showing everyone a thing or two… Previously, his boxing ring has been the world of rock ‘n’ roll and his victory has been million of fans. But for a while now, he’s been putting in long, hard days as he enters a new arena—movies—without a trace of entitlement. All this and much, much more, including movie-screen chemistry and actor authenticity, point to the news that everyday Jon Bon Jovi is becoming more and more of a contender in a game that only a short while ago wouldn’t give him the time of day.

INGRID SISCHY: Jon, every time I’ve spoken to you during the past year and a half, you were either going into or coming out of working on a movie. Have you always worked your butt off like this?

JON BON JOVI: Yes. My real friends and my family know that if I’m not working I’m miserable. It’s not for monetary reasons. I already have fame and fortune. Now I want to find the greatness in things—which is why I was attracted to the arts in the first place. Slowly, I have fallen in love with acting. And all the struggle here—the acting lessons, the indie movies—has taught me so much.

SISCHY: At what moment did you say to yourself, “I want to make it as an actor”?

BON JOVI: People had come to me over the years, saying, “Why don’t you get into movies?” But the truth is, I had too much respect for acting and actors to think that just because I was a singer in a rock band I could do this. Initially, it was only because I wrote the soundtrack to Young Guns II [1990] that I was introduced to acting. When I first went to the set, I realized how shallow I had become, because the only thing I knew how to do was write a record and tour. One of the great silly regrets I have is never having worked on the boardwalk for a summer and blown a summer spinning the wheel. I would have loved to have that freedom and fun as a kid, but I always had a band, and I was always rehearsing and playing a block dance or something, because I wanted to play music so much.

SISCHY: I’m going to want to talk about the music, but for now keep telling me how the acting thing developed.

BON JOVI: After that experience with Young Guns, which was frustrating from the music side, I decided to study acting, or at least find out about screenwriters and playwrights. Initially, it was to get my hands on great movie material to write songs for. People told me about this New York acting teacher, Harold Guskin. He wanted me to audition, to see if I was serious. I went to him with my legs crossed, arms folded. I had no way to emote whatsoever. Basically, I paid Harold Guskin $150 an hour to tell me, “Okay, you suck.” I stayed with the lessons for two years. I started to read these classic plays and get ideas, and I also began writing songs for what became Keep the Faith [1992].

SISCHY: When was this?

BON JOVI: Around 1990, after Slippery When Wet [1986] and New Jersey [1988].

SISCHY: They were monster-big albums.

BON JOVI: Yeah, they sold in the eight digits. I was burnt out, physically and mentally. I was disillusioned. I got rid of the managers, agents, lawyers, almost everything. Eventually, I came out of my shell, started writing material again, and the band came back together and we progressed.

SISCHY: When I met you, I was surprised, given your level of success, that you had both modesty and a sense of self-perspective. You had become this giant thing, but you weren’t busy making sure everyone knew it.

BON JOVI: Hey, I know I’ve sold more than 75 million albums, and that’s a lot of fucking records. I’ve outsold my peers. But I don’t feel the need to puff my chest out.

SISCHY: Why not?

BON JOVI: I’m older. I’m humbled.

SISCHY: Were you ever full of yourself?

BON JOVI: Sure, during Slippery and New Jersey. And a lot of that arrogance, in retrospect, was out of fear of the success not being there forever. People who have to tell you how successful they are aren’t really successful. That’s something I learned sweeping floors at this recording studio called the Power Station. Mediocre stars were the biggest pricks, and the big stars were the ones who came in and said, “How’re those demos going? Keep pushing, you’ll get it. It’ll happen for you.”

SISCHY: Go back even earlier.

BON JOVI: I went to Sayreville High School, in New Jersey. I was a loner. Both parents worked six days a week. I played in bars starting in the late ’70s. it was hard, but it was magic, too, because I was lucky enough to be in Asbury Park when it was in its last stages as a scene. This was after Springsteen, but you still had the feeling that the next big band could come from there. I guess it was a little like that in Seattle a few years ago, or anywhere else where a music scene has happened. In my day, the only way to be successful was to play covers. But I realized in high school that the only way to get out of that scene was to play my own stuff.

SISCHY: And from there, the story is legend. But what’s interesting is how you’ve prevented yourself from being dehumanized as a legend. You’ve obviously been committed to keeping the realness factor. Let’s be candid: Often, with the music, the critics have been busy with what you’re not. For instance, the way they’ve seen you compared to Springsteen.

BON JOVI: Second place, sure. I’ve known the guy since I was 16, when I first played with him. We’ve played countless bars together. Obviously, I’m always going to be in the guy’s shadow, coming from the same place but later. But I don’t resent that. I would never have wanted to be a musician had it not been for Bruce and the E Street Band. And Southside Johnny. And Little Steven. Those were my heroes. So yes, I’m in Bruce’s shadow. But no, I don’t want to be him.

SISCHY: Thinking about this interview and the image I have of you, I kept flashing on Rocky.

BON JOVI: Yeah. And you know what happened to Rocky: In the second and third movies, when he’s on top of the world, he gets his ass whupped and goes back to find out what it was that he loved about boxing in the first place. Even with all the success, I wanted to find out again what I love. And now I’m in a completely different head. Fortunately, unlike Rocky, I didn’t lose everything I had.

SISCHY: One of the components in your success, and something I’m sure you’ve though about, is the way you look.

BON JOVI: It’s both helped and hindered me. But that’s okay. Ten or 11 years ago, when Slippery hit, I was very excited about being on the cover of Rolling Stone. Then their reporter turned up, and all she could talk about was, “You’re so cute. And your hair!” I thought to myself: “If you want to fuck me, let’s just get on with it.” I was very angry about all of that. But what could I do? Scar my face? Knock my teeth out? After a while, I learned if they’re going to say all I am is a pretty face, then they’re not taking the time to look at the facts, which speak for themselves.

I’m not just talking about the work facts, but the personal facts, too. How many guys would have left their wives when they found fame and fortune? Why would I get rid of my wife for, you know, Michelle Pfeiffer? It would be a stupid move. How many guys would have left their friends, fired the band? I haven’t, because these were people who believed in me 17 years ago. I wouldn’t be able to sleep or go on if I didn’t acknowledge them and give back to the people who gave to me. There’s a lot of people, executive types, who say to me, “Why go backwards? You’re getting all this great acclaim now.” I’ll tell you why: because none of it is going backwards.

SISCHY: To them maybe a guy who is willing to start from the bottom when he’s on the top is a notion they don’t know how to deal with. But in fact it’s what artists do all the time. So take me back to Jon Bon Jovi spreading his wings as an actor.

BON JOVI: It was supposed to be with Norman Jewison, who, you know, is gigundo, and he was doing a film called Only You, here in New York. The band was playing in Boston. Jewison was interested in me for a part. So I flew down, and I was sitting in the lobby, and this big actress was there, too. Forty-five minutes of her harping in my ear about dribble. I became very crazy. I panicked, and I got up and walked out. It was a year later, and another year of lessons on and off, before I went to audition for a part in Moonlight and Valentino [1995], which I eventually won. It was a slow process. Each step was a baby step.

SISCHY: It was funny with Moonlight and Valentino, because you could almost sense how surprised the reviewers were that they thought you were good. But they had to give that to you. And since then, you’ve obviously been working your ass off. None of the films have come out yet, but you’ve been filming back to back, right, and are about to start appearing—how many are there?

BON JOVI: Five: The Leading Man, Little City, Homegrown. Then there’s Eddie Burns’s new movie, No Looking Back. And last, Row Your Boat.

SISCHY: None of them is big-budget. Most of them are independent. It could be that not one of them will be a hit, or even seen that much.

BON JOVI: Correct.

SISCHY: Little City, which is directed by Roberto Benabib and is expected out in late February, what is your role?

BON JOVI: I play a guy who’s a recovering-alcoholic bartender. The movie is very much a Big Chill kind of thing. Nobody’s incredibly successful, and we’re all looking for life. It’s a really nice little movie.

SISCHY: What about doing a big-budget movie?

BON JOVI: I’ve read a lot of scripts for Hollywood movies; in fact they wanted me to go out to L.A. for something tomorrow, but I said I couldn’t do it. I don’t see myself on a spaceship saving the world, and that’s basically what the story was. It’s more important to me to do a script and a character I can learn from.

SISCHY: Now that you’ve done several movies, I imagine that some of them have been rewarding…

BON JOVI: Yes.

SISCHY: …and some have been shitty.

BON JOVI: Yes.

SISCHY: But something’s keeping you acting.

BON JOVI: Well, on most of the projects I’ve done there’s no budget, so you don’t know if anyone’s ever going to see the film. People are there because they want to be. No one in these movies is making a million-dollar paycheck. They’re labors of love. When you look at Sean Penn—who, to me, is the pinnacle of the actor of my generation—obviously Sean could do movies for money every day of the week. He chooses not to. In the same way, for me to rewrite “You Give Love a Bad Name” just because it was successful would be a cheap shot, and I gotta look in the mirror when I shave in the morning. It’s more important to me to try to find the greatness in things.

SISCHY: Give me some lines from one of your songs that express that.

BON JOVI: Okay. They’re from “Livin’ on a Prayer”: “We gottahold on to what we got / It doesn’t make a diference if we make it or not / We got each other and that’s a lot / For love, so we’ll give it a shot.” That’s the essence of the song. You know, I became a recording artist when I was 20, 21. I made my first million by the time I was 35. It means shit to me. What matters is not all the commercial success but the heart that went into that: five kids from Jersey doing what they wanted to do. Same thing with what I’m doing now, in both the music and the movies.

THIS INTERVIEW WAS THE COVER STORY FOR THE FEBRUARY 1998 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.