Mark McGuire’s Programming Notes

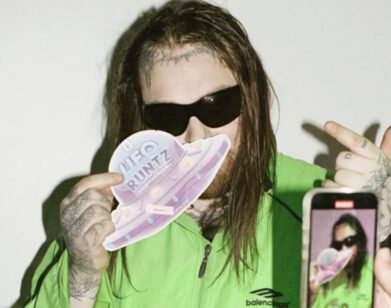

ABOVE: MARK MCGUIRE. PHOTO BY CHRISTOPHER GABELLO

We met the massively prolific guitarist Mark McGuire, of the late, great Cleveland electro-ambient champions Emeralds, in a South Brooklyn record store and antique shop called Black Gold. He’s found himself in New York City to perform for the first time in nearly two years—this time solo, at Baby’s All Right, tonight, Friday, January 31. It’s about as bittersweet a show as you can get: a headlining spot at one of Brooklyn’s best new clubs, but his first performance in the city since he parted ways with Emeralds. Despite that, McGuire’s having a good year so far. His new record, Along The Way, comes out on Dead Oceans February 4. And that’s not to mention his appearance on a new record by The Afghan Whigs—he might even show up for a few sets on the Whigs’ tour. We talked about his nomadic tendencies, “The War on Consciousness,” why even experimental music is restrictive, and letting go of his band.

DALE EISINGER: When did you move to Los Angeles?

MARK MCGUIRE: I’ve been going back and forth between Portland and L.A. for a year and a half. I finally got a place there a few months ago, so I’ve actually got a secure spot and everything.

EISINGER: What was appealing about L.A.? I’ve been seeing a lot of “Los Angeles is the next great American city” kind of praise.

MCGUIRE: It’s weird. I never kind of do things for those kind of reasons. I moved to Portland because my friend Spencer [Clark] was living there. We were working on music together around that time. And he said, “If you were out here, we could be working on stuff a lot more.” That was the same reason I went to L.A.—I went down there to work on a film score and the producer said, “If you lived here, we could do this all the time.” That, coupled with my appreciation for Mexican food and even just the scenery and the surreal, almost psychedelic quality that Southern California, and the West Coast in general, was very appealing. Growing up in Cleveland and then getting out there is a cool change of pace.

EISINGER: In regard to scenery, there’s a video interview where Emeralds went out into the woods of Ohio and gazed out over a canyon, saying, “this is what we do when we have to get away.”

MCGUIRE: That was our spot that, even before Emeralds started, that we would go and hang out. A lot of the imagery in our music was inspired by places like that. Portland was a great move because it was that kind of setting but even more so. There’s even more kind of lush greenery. And then L.A. flips that a little bit, almost to a tropical aspect of Southern California. It’s nice to be in a city where you can at least escape and end up at the beach or at Malibu or the desert.

EISINGER: What music were you working on with your friend Spencer [of Skaters, Monopoly Child Star Searchers, Dolphins Into the Future, etc.]?

MCGUIRE: We put a record a record out together called Inner Tube. It’s a tribute to a lot of the Australian surf movie culture from the ‘80s, as a basic frame of reference. It was taking a lot of imagery that we were getting inspired by surf movies and general water sports, like Jet-Ski and even sailing competitions. This kind of vibe that every surfer bro thinks he’s a spiritual dude or whatever. But there is that spirituality of being out on the water and being on that cusp between man and nature. We wanted to infuse that with the kind of sounds and moods that we would associate with surf music. The record is a tribute to things like that.

EISINGER: What was the film you scored?

MCGUIRE: It was a film that was called, at the time, Get A Job. I think they’ve changed the title since then. I’m not sure of the status on it at the moment. But it was a total Hollywood production. The producers had done a lot of films. They did Reality Bites, Pulp Fiction, Garden State… a lot of stuff. This one was a hybrid, kind of coming-of-age, life-lesson, stoner comedy. Maybe it’s not the first film you’d imagine my music in, but that was cool for me because I got to see my music in a different context. And then it inspired me to create a lot of new atmospheres.

EISINGER: Which are all over your new record, as opposed to your earlier work.

MCGUIRE: Absolutely, yeah. I started Along The Way while I was still living in the studio that I did the film score in. The two things were really influencing each other.

EISINGER: You said this wasn’t the ideal environment for your music. What is the ideal environment for your music?

MCGUIRE: Well I think a comedy wouldn’t be the first thing I associate with it. I can see my stuff being used more for soundtracking a documentary or something more stoic or somber. Something of a different mood than lighthearted, joking around about weed.

EISINGER: But your new record is a lot more lighthearted, a lot more accessible, than your previous work. There are drums and hints of pop structure. How did you come to that?

MCGUIRE: I was starting to get to the point where I had been doing solo guitar music for a little more than six years. And I was starting to get a little frustrated with wanting to get a broad range of sounds out of guitar. It’s not like I was consciously saying, “I want to make it more accessible,” or anything like that. I really just, when I started, said, “I’m not going to worry about putting any boundaries or preconceptions of what this should be.” It was more about letting the ideas and the songs kind of fall where they did. And I just happened to be living in a studio where I had access to a lot of equipment and instruments that I would not normally be able to use. Part of me just said, “You have to take advantage of the fact that you’re here right now.” Otherwise, what’s the point? The instruments and the preamps and the mics and everything… it ended up taking shape in the form of Along the Way.

To a certain extent, you can call it more accessible, just to the average person or something like that. But I would also think that the flipside of that is that someone who’s more accustomed to the music I’ve made in the past would like to pick up this record and enjoy it, without it sounding like the old stuff. I care deeply about anyone who listens to my music. That’s a sacred connection between the artist and the person who appreciates what you do—it’s beyond words how meaningful that is. But I’m not going to stifle myself from trying new things because I feel like people that are already into my stuff might not like it.

Getting into freeform and experimental music is really great until you start telling yourself that it has to be experimental or it has to be this or it has to be that. Then it’s the same thing as being in a metal band and everything has to be metal and it can’t be soft, it can’t be this. It’s the same kind of programming yourself. And I was just at a point where I was, again, trying to deprogram myself. Because when Emeralds started, that was literally us trying to unlearn everything we had learned about music up until that point. Especially John and I, because we had played guitar since we were little kids, and grew up with all these ideas about what music is supposed to be and what we were doing with it. We decided to rediscover what sound and music and that whole exchange is.

So when I started working on this album, it was the same thing, where I was realizing how much I was starting to become programmed by the world that I was involved in and wanting to not worry about that so much. I was working on this film and it was so far removed from the world that my music exists in. That aspect of it alone gave me a broader perspective on things. People were very enthusiastic about things to the point they used my name as a verb. “You should McGuire here a little more, but I wouldn’t McGuire there.” It’s almost goofy. But it was an environment devoid of pretension in regard to any ideas that I might have. I think it influenced me to be more open-minded with my own sound and realize that it’s something that’s constantly going to be evolving. The range of thoughts and feelings that I convey, I don’t want that to be more and more narrow as I go along. I want that to be more and more open. With this record, I just followed my heart and my gut and I’m really happy with how it turned out. Ultimately, the spirit in the music is the same.

EISINGER: It’s interesting that you would start to get programmed by the experimental world when that’s supposed to be a space for a kind-of liberation of ideas, a free-for-all.

MCGUIRE: Tell me about it, man. That’s what I was saying to myself, basically. And I noticed it more—not trying to name names or anything—but with certain other people I’ve interacted with in music. Some people are so militant. If it’s not avant-garde or if it’s not “so weird” it doesn’t even count, it doesn’t even rate. With the electronic underground or experimental, there are so many subsections. You just find yourself in places where, yeah it’s experimental. But “experimental” can almost become like punk music. Punk rock is a spirit of music and a state of mind rather than a sound. But once it did become a sound, it became the furthest thing removed from what punk rock really was. I think experimental music can do the same thing. You’re experimenting with something that’s not really an experiment any more. You’re working within a formula that’s already been done and already been approved by your peers. There’s nothing really experimental about the moment or the process of it.

EISINGER: It’s meant to challenge.

MCGUIRE: Exactly. And to challenge yourself. I consider putting out a record that a bunch of people who like your stuff might totally hate more experimental than if I were to put out another droney guitar record. Not to say that one way is right or wrong. It’s just something I started to notice. It’s weird when you’re in this space that’s supposed to be open-minded and freethinking atmosphere and you wind up not feeling like that.

EISINGER: What you’re talking about reminds me a little bit of when Thurston Moore released Demolished Thoughts. It was a collection of acoustic songs.

MCGUIRE: Look at the career of Bob Dylan. When he started playing with a guitar and with a band, people were so against his new thing because he was trying something. You can’t let other people dictate what your art is supposed to be. That’s the opposite of art. You should constantly be challenging yourself to grow and change and create and evolve. I’m into that spirit of experimental and underground music. The constant, the groping, seeking, moving forward, regardless of where it might take you at that moment. It’s all part of a larger arc.

EISINGER: Has it been hard to let go of Emeralds?

MCGUIRE: Absolutely. I’ve never experienced anything in my life that had more personal meaning to me and where I felt like I was doing what I was supposed to be doing. Emeralds came out of a time when none of us had anything going on. We barely knew any other people who were doing anything remotely weird or cool. When it happened for us, it happened totally spontaneously from the ground up. Those guys are my best friends. We went through a lot together, even before the band started. Going through everything, even just finding our footing in the music community. Or going to Europe for the first time together, or traveling around, or getting ripped off, getting in car accidents on tour… we went through so much together. Even before I left the group, no matter what’s going on, time passes and it becomes something else. You can tell yourself over and over, even when you’re getting attention and people are lauding your stuff, you can say, “Don’t listen to that. Just do your thing.” But ultimately, things have a way of running around in the background of what you’re doing. You can have all the best intentions in the world. But things can start to move in different directions. The three of us were just at a point where as people we moved in different directions. It didn’t seem like the spirit and the heart and the soul of our band was there the way it was. That alone broke my heart.

EISINGER: It seems like this new record has more emotional heft than your work in the past. Did you channel any of those feelings about the dissolution of Emeralds into Along The Way?

MCGUIRE: I think naturally that just happened. I think that even filtered its way into the last Emeralds record, even unconsciously. There is a lot of personal stuff on the record. And a lot of it has to do with our band but more so just looking at your friends and yourself and having to stop and ask, “Am I really being honest with myself about things? Are we really being honest with each other?” That was happening with the guys in Emeralds and my friends and people in my life and my family. It was just a time of reassessment for me. A lot of the stuff in the record I’m talking about has to do with that but also a lot more.

EISINGER: What is “The War on Consciousness?”

MCGUIRE: The character in the story of the record is supposed to, obviously, be autobiographical in some way; but is definitely not supposed to represent me as a person. “The War on Consciousness” happens near the end of the story and the character here goes through all these realizations. It’s pretty obvious there’s a lot of corruption in the world right now. That takes many forms. There’s economic, political, religious, social corruption. Just the manipulation that takes place with all the information that people are given, and even just the way the world is presented as this concrete block, this concrete idea that there’s not really an alternative at this point in the world. You can’t really go off and live your own life off in your own world. Which is what this country was supposed to be when it was founded. But it’s literally the opposite of that now. “The War on Consciousness” is really all those physical manifestations and all those problems are ultimately just a war on your way of thinking. Especially now, when we’re involved in the war on terror. Terror is a psychological term. Terrorism is a political term. Terrorist is a sociopolitical term. But terror is a psychological thing. All the things you hear about, especially due to the nature of how we receive information, not even second—or thirdhand anymore, but 25th-hand at this point. It’s really distorting the way you view the world. It’s ultimately a war to keep you afraid and keep you in a state of anxiety and worry and misdirection and absolute confusion. If you look around right now, there are so many layers that comprise the world. You don’t even know where to start. The technological age we’re in now is the perfect forum for constant misdirection and constant distraction. I ultimately think it’s a war to keep people from realizing the true nature of themselves and the true nature of life. All the things people are in pursuit of now, in 2014, are total illusions. It just destroys people’s happiness. Authors like Michael Tsarion first brought this to my attention.

EISINGER: You brought up the word “nature.” In regard to your music, it seems like you’ve taken a path from writing about “nature” with a lowercase n to writing about “Nature” with a capital n. A Young Person’s Guide to Mark McGuire, for example, had a lot of direct references to the natural world; this record seems more cosmic.

MCGUIRE: I would say that’s so just because I’ve only just begun to understand why I have been drawn to those aspects of the world. In the past few years, I’ve gotten really into reading up on certain subjects and philosophies, and obviously about psychology and things like that, realizing so much that the only real connection that mankind has truly ever felt is to the natural world. When people existed in a simpler time, they had more of a personal interaction, there wasn’t so much clutter around, distracting from the fact this world is infinitely incredible and amazing and miraculous. I started to realize what my appreciation for that was. I do believe my personal spirituality, which spirituality itself I don’t really equate to anything more than my personal connection with nature and the universe. With what is real, not a manmade contrivance. Finding a connection with those things through my music is something I’ve begun to take more seriously in order to understand why I feel that way.

MARK MCGUIRE’S ALONG THE WAY IS OUT FEBRUARY 4 ON DEAD OCEANS. MCGUIRE WILL PLAY TONIGHT AT BABY’S ALL RIGHT IN BROOKLYN. FOR MORE ON THE ARTIST, PLEASE VISIT HIS FACEBOOK PAGE.