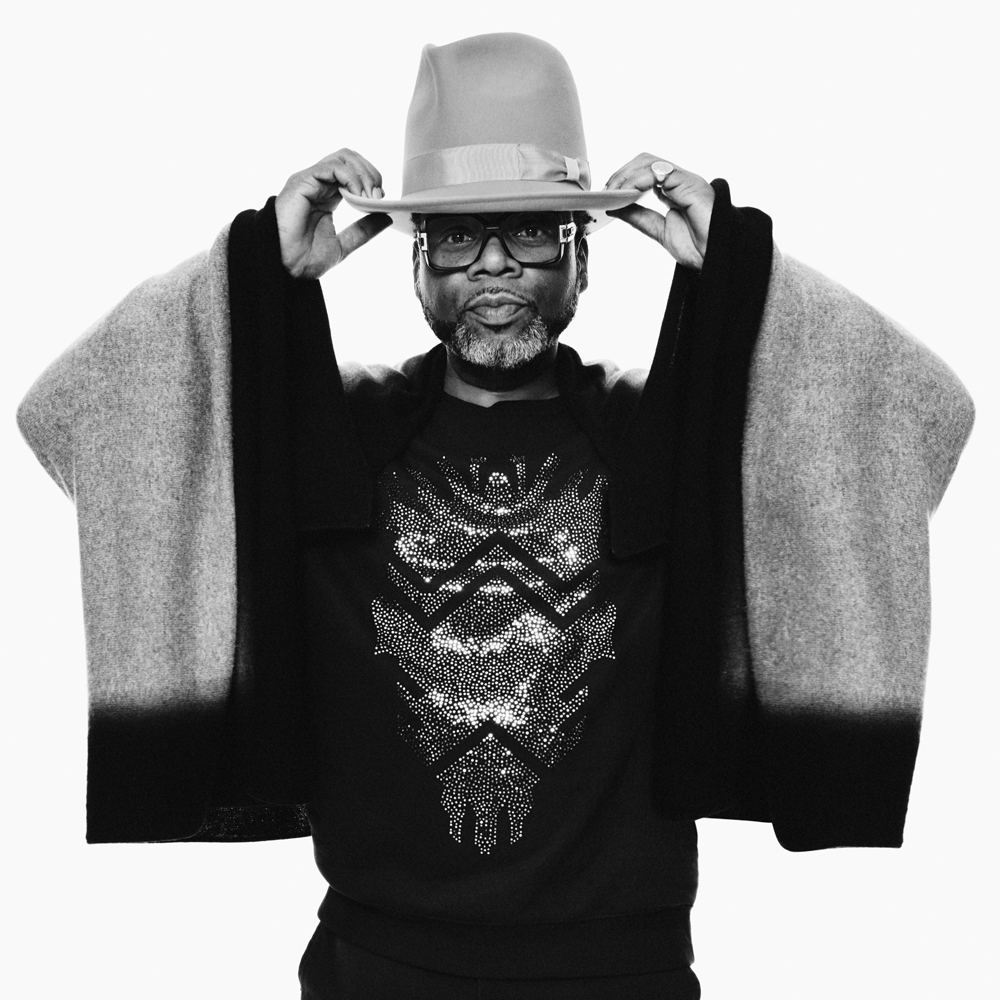

Jazzie B

London, summer of 1989—it seemed like Soul II Soul was floating out of every car sunroof or shop doorway. “Keep on Movin’,” “Back to Life,” “Jazzie’s Groove,” DJ and producer Jazzie B’s clever balance of reggae, soul, dub, and hip-hop—a mix as much about attitudes as beats—distilled all of young London’s multiculti, pan-racial cool into one infectious groove, a multiplatinum album modestly titled Club Classics Vol. One.

Remarkably, Soul II Soul got there in spite of the conventional record industry of the time, rather than because of it—a product of the local, below-the-radar world of sound systems. Increasingly influential on urban culture, sound systems were born in 1950s Jamaica as an alternative to the established music business, with operators running open-air dances, spinning records on powerful equipment, and producing their own music, shifting styles and sounds to stay ahead of their rivals. If a tune played well, they’d press up a few hundred to distribute from a box on the back of a motorbike.

In England in the 1980s, a young “Jazzie,” as Trevor Beresford Romeo had begun calling himself, immersed himself in this DIY culture, taking his sound system beyond the dancehall by creating a chain of Soul II Soul shops, selling his take on clothes, shoes, records, and accessories—one store even had a barber. One of the shop’s biggest sellers, in the tourist hotspot of Camden Market, was the “Funki Dred” T-shirt bearing Soul II Soul’s logo, so that, before they’d even released their first record, an entire world knew who Soul II Soul were.

After a series of one-off “specials” made to play at their club nights, one song, “Fairplay,” attracted so much attention that A&R men began queuing outside Soul II Soul dances. (Jazzie says he finally signed with the one who “got it, and essentially left us alone.”) Eventually, the likes of James Brown and Maxi Priest would make their way to Jazzie’s studio, and he’s done remixes for Public Enemy and En Vogue, among many others. Meanwhile, the group’s visual style, as well as their explicitly inclusive maxim, “A happy face, a thumpin’ bass, for a lovin’ race,” had huge cultural significance in 1990s Britain—a significance that has not dimmed in the years since. When speaking to dubstep, grime, and jungle artists for my recent book Sounds Like London: 100 Years of Black Music in the Capital, for which Jazzie wrote the foreword, the phrase I heard most frequently was, “When we saw Jazzie B do it, we knew we could, too.”

LLOYD BRADLEY: How did we meet?

JAZZIE B: I feel like I’ve known you forever. [laughs]

BRADLEY: Well, we both come from the same area, Hornsey. Both got similar backgrounds, with sound systems, dances, that sort of thing. And you’re, what? Six, seven years younger than me?

JAZZIE B: ‘Bout that, yeah.

BRADLEY: But I think we actually met when your record company asked me to write a bio on you.

JAZZIE B: An EPK. Fuck, those things are old. So this would have been in the early ’90s?

BRADLEY: Yeah, because I remember when I was at Q Magazine, I tried to get a quote off you for a piece I was doing. You were being awkward, and I told the lady who answered the phones in your office, “Look, it’s fine. I’m going to make something up, and maybe I’ll run it by you.” You got on the phone about 20 minutes later.

JAZZIE B: [laughs] What an introduction.

BRADLEY: And then we realized that we’d grown up on the same streets, more or less. We’d been to the same dances, all around Crouch End, Hornsey, Archway.

JAZZIE B: A lot of people in common. And then, obviously our Holy Grail …

JAZZIE B AND BRADLEY: [in unison] Arsenal. [both laugh]

BRADLEY: I remember I’d heard about Soul II Soul sound system before then. It was really the shirts. I saw these Soul II Soul shirts before I can consciously remember hearing Soul II Soul music.

JAZZIE B: That would be quite cool actually, because the shirts were part of a campaign that we had, going to clubs in the early days. We just wanted to be identified outside of the general crowd. The idea was to have T-shirts and stuff like that with our logo on them that would enable the crowd to identify with the people running the events. That kicked off when everybody wanted the T-shirts, and we printed out a load to go to [Notting Hill] Carnival. I’m quite sure they were all sold out in the first run. So that added really nicely to my whole idea of world domination, by knocking them out on the Market store, because the store was based in Camden Market at the time, doing a lot of bric-a-brac things. I decided to do the sound-system thing 24/7, as opposed to a hobby, so we needed a way of having revenue to keep it going, and that was the introduction to the whole idea of the Market.

BRADLEY: I can remember your store in Camden Market did sell jeans, like repurposed stuff, that whole kind of peg leg jeans and round float-jacket look was there, wasn’t it?

JAZZIE B: Yeah, that was very much the look in quirky, punky Camden at the time. We weren’t, like, über-fucking trendy or anything like that, but we had our own way of looking like an individual. And we ended up taking on this whole sort of energy. I mean, London, Camden in particular—the cobbled mews, the old lights, and the architecture at the time—was still very derelict, so that went sort of hand in hand.

BRADLEY: There were the soul clubs, the reggae sound systems, the blues dance thing. And nothing particularly stood out. It didn’t seem to reflect life in north London. You guys, with how you looked, your haircuts, everything was more about what was actually bubbling up, not what’s been there for 20 years.

JAZZIE B: I mean, we set the tone like that. We’re talking about early ’80s, and all the other nonsense that was happening in London on the black scene, as it were. We’d approached the whole club world from a different perspective, turning around the idea of the sound system and actually making it a one-stop shop. A lot of that was derived from following the older sound systems. It was more community centers and church halls and so on. We just evolved to where we were tired of the hand-me-down-type things. And the idea of us taking it to the next stage, which for my generation, the inclusiveness of all the other people around, particularly in the arts—we had so many things in common, and obviously the music was the underlining thread. But Camden was a new territory for us, and we didn’t stick out as much as we did if we were in Finsbury Park.

BRADLEY: No, not in Camden. Anything went in Camden. And it was hand-me-down culture. People still looked like, I don’t know, the O’Jays or something. They looked like old-style American soul acts. And at the reggae clubs, with all the Gabicci, they looked like they had for 20 years. And then suddenly there was no modern black identity. You saw that happening in America with the second wave of hip-hop. But it wasn’t happening over here.

JAZZIE B: I think when we came along, it was like a breath of fresh air, because it was probably the first time you were seeing black people that, in a way, you could really identify with. We weren’t dressing up in loincloths with curly perms, or just looking like fucking clowns, you know what I mean?

BRADLEY: It was black and white kids moving together. We grew up together, we had gone through school together, we chased the same girls together, we played football together—why not go to clubs together?

JAZZIE B: Music and fashion really do go hand in hand. This is even going back to the reggae days. Everyone on my street, we all went in to each other’s houses. And even in those days, with the clichés and everything else going on, there was a sense of naiveté and curiosity. Many lived on the streets like we did, with all the different mixing of cultures. And what stemmed from that was people’s cultural identity—you made much more of a thing about it, you know? We were all under the Union Jack, but it was very evident if you were West Indian, Nigerian … You load that up with a bunch of Irish kids and Greek people and stuff; it fixes to be a very interesting recipe. I’m born and raised in England; half of my family were born here, the other half were born in Antigua. So our view of it may have looked a little bit more pro-black, because the ones that were born in England seemed to be way more black. Being West Indian, we were holding up our heritage more so than our elder brothers and sisters, because they had to really fit in. So when we came along there in the ’80s, it was a serious time for us to cut our teeth, and we really wanted our own identity.

BRADLEY: It’s gaining this identity, but not merely a black identity, but a London identity.

JAZZIE B: Yeah! We looked in the mirror every day, so we didn’t have the same sort of vibe like the intellects or journalists and editors of magazines, where they were appeasing to this, that, or the other. We weren’t fucking compromising in no way, shape, or form. We got the same shit from black people as we did from people who didn’t understand us. And the best times is when we went up north as a crew, to places like the Haçienda, in Manchester, places like Liverpool, and getting chased, the bus getting smashed to smithereens, because they knew we were from London. And that was part of us growing up. But in every place we went, somebody would identify with us, whether we were physically aware of it or not, because there were representatives from all of these clans. I guess it’s a testament to Soul II Soul as a sound system, because we were much more about having a broader perspective on the whole raving in our culture. For us, it was really important to go to Liverpool, to go Manchester, to go to Chapeltown and all these other places, absorbing the culture and spreading the word.

BRADLEY: When you were a kid growing up, were you looking to this as a way forward? Because you’ve been involved in sound systems since you could walk.

JAZZIE B: Well, from the early days, watching my brothers, I had a real great bird’s-eye view of everything that was going on in the sounds. And in terms of my vision, I used to visualize a bit like, I guess, Dave Mancuso would have done in the disco ages at the Loft. Our parties were in houses, initially. Blues parties. So you went and identified a room. One of the things a lot of people didn’t know was that in the early days of Soul II Soul sound system, we got burned out of a building in Hackney by the National Front. They had blocked the door and put a petrol bomb in there, and set it alight or whatever. So that was one of the things we were fairly aware of-the exits. We didn’t need any deaths or tragic things happening. So you have to understand all of these elements were part of what we were coming through.

BRADLEY: If you were to explain what a sound system was to someone who’d never seen one or heard one, what was sound-system culture about?

JAZZIE B: For us, the sound system was really a way of life. It was about us transporting our messages, keeping up to date with what was going on back home. But then, being born and raised in Britain, a lot of it centered on our culture and our ideology—and just the beauty of the fact that we could flex, meaning that white people were involved in your sound system, so ideas, equipment, and technology took on a slightly different slant. Now, describing Soul II Soul sound system against Sir Coxsone Outernational or Jah Shaka, you’d think you’re in two different worlds. But the difference with us is that we were, I guess we’d use the word “trendy,” or a little bit ahead of our time—the idea of mishmashup, putting different things together that suited us, had an identity character.

BRADLEY: But it wasn’t just putting the speakers in and setting the amplifiers up. You dressed the room. You’d all wear T-shirts. You had a haircut … You entered Soul II Soul world.

JAZZIE B: It was about having a true experience, whether we had capacities of dozens or hundreds of people. So this would have started off in a 60-person party, going all the way up to, you know, a few thousand people in a club, and us controlling it. But when you walked through those doors, it wasn’t warm, it was hot. It wasn’t bright, it was vibrant. And, as well as the banging music, there was art. It was our version of hip-hop, the full lifestyle, the attitude. So it was more about vibes, where an old sound person could walk in and literally feel at home, your average middle-class kid from Highgate, in the suburbs, will feel at home, and some of us bohemians just felt like, “Yeah!”

BRADLEY: It’s a real reflection of London, but pushed from a black point of view. And there was this whole fashion thing-you had a look; you had the Funki Dred logo. There was this sort of painting that went on in the clubs. By the time you ever made a record, you’d already created this notion of the Soul II Soul lifestyle that people were buying into.

JAZZIE B: Sound systems resonated that way quite a lot. You followed a sound initially for the type of music they played, and then for the people who followed them. I suppose we upped the ante a little bit with the fact that, from a visual perspective, were coming out of analog, moving into this digital, slightly clinical world. It made good sense for us to be as dusty and derelict as we were. It was so important for us to have an identity, like. It’s about England. It’s about London. This is where I was actually born and raised, the backstreets and the nooks and crannies; it was about all that. The shop was like a one-stop thing, and I know it sounds a bit Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, but we weren’t trying to be them, right? Because it wasn’t necessarily about us being all fucked up over the system, politically—God hate the Queen, all that. It wasn’t about that. The punk attitude sure helps, but we really were taken by the multiculturalism of London at that time, and how fucking exciting it was. Our thing was more reaching out to people who were far more open-minded, who were like us. I like to travel. I didn’t mind going to many places where there was a pocket of our black culture, whether it was borrowed from America or borrowed from Africa or even the Caribbean. It was happening! It was happening in all these places. So look how much that resonated in terms of what we were doing in music. And in the early ’80s, it was time for us to lay down our own gauntlet. We weren’t trying to copy or follow anybody. All of these things had influences on us, but it was really important for us to have our own identity, and Soul II Soul really was about us. I mean, when you start going further out from London, everybody wants to be with the origins, where we were much more about the hybrid of it all. And that was a really essential part because London isn’t a great reflection on the rest of England. But within itself, it is so unique and now, in 2016, you can go around Britain and see the influences that this has had. I’ll just take my hat off to the idea of the multiculturalism and how it worked.

BRADLEY: What’s next? You’re an elder statesman of sorts now.

JAZZIE B: Thank you. I don’t feel so bad. My children are growing up and we’re living in another time. What’s next for Soul II Soul? I guess it still resonates with “a happy face, a thumpin’ bass, for a lovin’ race.” We’re just going to keep on moving, and like brother Bob said, “Make sure the tide is in my face.”

LLOYD BRADLEY IS A LONDON-BASED MUSIC JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR.