A Troubadour’s Travels

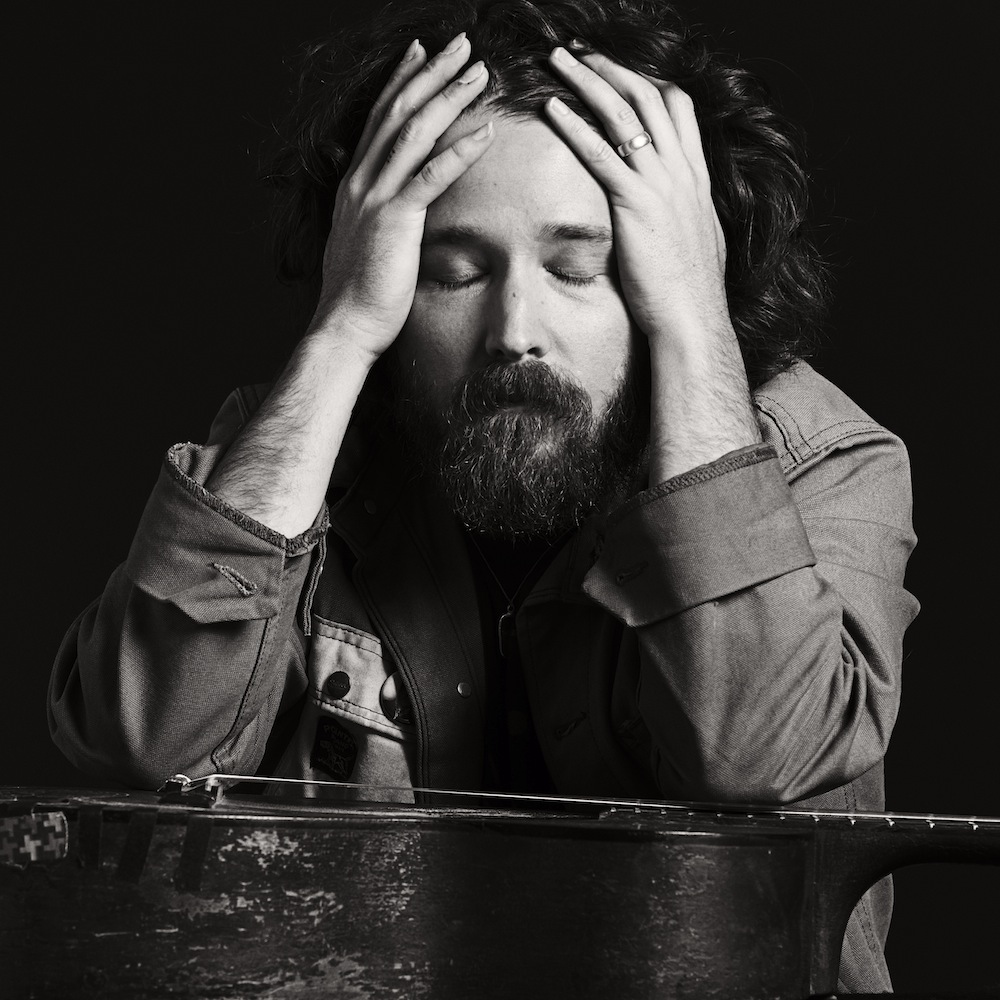

CHRISTOPHER PAUL STELLING IN NEW YORK, MARCH 2016. PHOTOS: CHRISTIAN HÖGSTEDT. GROOMING: TAKUYA SUGAWARA.

Folk musician Christopher Paul Stelling has been on the road for five years. In June 2015, the Florida native released his third LP, Labor Against Waste (ANTI-), then toured Europe and the U.S. on his own, and last month opened for Ben Harper & The Innocent Criminals. So while his apartment might be in Brooklyn, he’s only been in New York for a total of six weeks since the beginning of 2015. As he sees it, beginning in 2011, touring became his job—even before he had released his first two albums, 2012’s Songs of Praise and Scorn and 2013’s False Cities.

“If you’re going to do this as a living, then you have to work five or six days a week like everybody else,” the 34-year-old says. “I’m a performer. I’m not really a guy that makes records, I’m not that organized, but performance is a different story: I get to show up, see the people, play the show, talk to them afterwards, and do it again.”

When we saw Stelling perform earlier this year, we realized his stage presence is a force to be reckoned with. His adept guitar plucking and booming voice take on a breakneck pace, his zeal for performing palpable. There’s wisdom in his lyricism, too, which remains true to the storytelling tradition of folk music. On “Revenge,” the second track on Labor Against Waste, he begins, “You can drag my name through bleach and muddy water / See if I don’t still call you a friend until the dying ends / And if you ever thought you were in for nasty weather / I’d say go on and build a shelter out of my bones and skin.”

Save two guitar lessons at age 10, Stelling is self-taught and his abilities are grounded in his unwavering dedication to touring and playing. Today, he is, unsurprisingly, setting out on another tour, revisiting every city in which he performed with Ben Harper, but as the headlining act. In March, we spoke with Stelling over coffee at Savannah Stopover Music Festival on a rare day off for the troubadour.

HALEY WEISS: When did you start playing music? Do you have a musical family?

CHRISTOPHER PAUL STELLING: Nope, no musical family. I went to Catholic school and was in the choir in church. I started doing musical theater when I was in fourth and fifth grade—I did a lot of that. I got pretty comfortable on stage in general because of musical theater. It’s kind of always been what I’ve done, in some capacity or another.

WEISS: So you always knew you wanted to pursue music professionally?

STELLING: No, I spent a decade of my life trying to avoid the pursuit of it because the idea was terrifying. Now I’m comfortable but sometimes the scariest thing in the world is facing what you think you’re supposed to be doing, and you’ll do anything but that for a while. Then, once you start, it’s like, “Oh, wait, it’s easy. Why didn’t I fucking start this 10 years ago?”

WEISS: What made you decide to start pursuing it? Was it a conscious, “All right, it’s time”?

STELLING: The lack of the ability to do anything else. I was washing dishes and working in cafés and I just thought, “Enough of this shit.” Over that time I had started playing open mics and on the subway [in New York], just building up my repertoire and confidence. I had been playing five or six hours a day for 15 years and finally realized, “I don’t really have any other option. This is the only thing I’m capable of doing.” I became unemployable; I was always so distracted at jobs by the idea of what I should be doing, but I couldn’t face the fact that if I did what I wanted I would get fired. [laughs] It was a long, difficult road to get there. I never would have thought this would be my primary life.

WEISS: When you performed “Scarecrow” last night, you told a story about refugees and how you met some of them in Europe. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

STELLING: I wasn’t really sure what the song was about, but when I encountered the refugee crisis in Europe that song really resonated with my feelings about it. In hindsight, “Scarecrow” became about it. I always will talk my way into a song—sometimes it’s a joke and sometimes it’s a story, but it’s important to set the stage for a song a little bit. When I was in Europe in July, I was traveling from Calais into Dover and that was the first day that there was a dock strike, which really backed up traffic. The immigrants that had gathered in Calais—it was a very small number at the time—tried to break into some trucks to get into the U.K. These people had traveled from Syria and Africa on boats, mostly to Greece and Italy, and then traveled across and were trying to get to the U.K. That was the day that the shit really hit the fan over there; everybody became aware that there were these people gathering, trying to get into the U.K. to work. This February, I was there and the situation was massive. There was razor-wire fencing in what looked like interment camps, with people living in plywood shacks in the mud while it was raining. It was inhuman. Two days after, I went through where the French and the U.K. bulldozed the entire camps and displaced these people even further. There are a lot of really good people, a lot of young people, working very hard to bring awareness to it.

At a show in Germany I dedicated that song to all of the people that were caught up in the crisis. After the show I met a group of young men from Syria who were refugees and it was really good to put a face on it and make friends. I know about the situation but hearing it first hand from a real person, that’s a whole other level of dimension. There are a lot of stupid things that the media does in the U.K.; they keep calling it an immigrant situation, and there’s a big difference between an immigrant and a refugee. An immigrant or migrant is someone that chooses to go somewhere and a refugee is someone that’s literally displaced. That’s the difference, and people need to realize that. That’s why it’s important to just be a human and talk about it. I’m not an advocate, I’m not an activist; I’m a human and it bothers me. That’s the first step.

WEISS: Being on tour, I’d imagine you meet a lot of people but also spend a lot of time by yourself. Do you consider yourself an introspective person?

STELLING: Yeah. I was an only child and I could just sit and entertain myself in my room by myself for three days. I’d make up stories or just imagine things, stare at the wall. I had a rich inner life as a kid. I would play more in my mind than I would with toys; I’d rather imagine a toy than play with a toy. I love human interaction, but I also love time to dwell, process, and think a little bit.

WEISS: What’s the most difficult part of touring for as long as you do?

STELLING: [pauses] I wouldn’t have it any other way, actually. It’s not that difficult for me. It’s good. The difficult part is going home for a week and waking up and being like, “What am I doing today?” Then I maybe drink too much coffee and spaz out. I catch up on a million emails so I can go back on the road. What keeps me on the road is the fact that I don’t really want to go back to New York.

WEISS: Is it because you don’t want to stay still or is it the city in particular?

STELLING: I love New York, it’s got an energy, but it was a springboard into doing this, I guess. I don’t want to tour like this forever but if you want to have anything that resembles a career in art these days, especially in the kind of stuff that I’m doing, you have to work hard for a long time. You’ve got to keep at it for a while, I think. That’s the experiment.

WEISS: Do you remember the first record you bought?

STELLING: When I was a kid, there used to be the BMG Record Club, where you’d send them a dollar and they’d send you 12 CDs. A lot of kids got in trouble, because you were also obligated to buy a $20 CD once a week, or something like that. You’d get all the Primus CDs, all of the Nirvana stuff. It was genius marketing. I remember doing a bunch of those, but Nirvana’s Nevermind [1991] was probably the first record I went to the store with my own money and was like, “I want to buy this.” It was the last time MTV ever told somebody they needed something and they actually did. [laughs] Maybe, I don’t know, I’m old now.

WEISS: How did you get into folk music?

STELLING: I think there’s a difference between the type of folk music that people put into the box of “folk music” and then there’s the kind of folk music that I aspire to and am in awe of, and that is the kind of folk music where it’s very limited tools—in most cases a guitar, in a self-taught style that is idiosyncratic and particular to that musician. None of this Peter, Paul & Mary happy-go-lucky ‘60s folk revival stuff. I have an affinity for old blues guys, like Skip James or Howlin’ Wolf, even the old Sun Records stuff—everything from that to Hank Williams and old country music or gospel music.

A lot of those people in the early part of the 20th century referred to their music, no matter what genre it was, as folk music, which just meant “people music.” There was classical music, highbrow music, and people music, which was folk. It was only later that all of this meaning got associated with it. Bill Monroe didn’t think he was playing bluegrass music; that was his own particular style of music and now it’s like a religion. Blues musicians thought they were playing folk music but because they talked about having the blues so much, it became blues music. Hank Williams talks about folk music and he was influenced by gospel music. It was the folk music of their day, but after the fact, marketing tells us it is country music. The idea of folk music to me is that everything, essentially, at its core, is folk music; it’s a way of running a thread through everything and trying to see the interconnectedness. It sounds stupid, but it’s more of a state of mind.

WEISS: Something that’s so impressive about watching you perform is the speed at which you can pluck the guitar strings. Did you watch other musicians to learn that technique?

STELLING: [I listened to] Dock Boggs, Hobart Smith, Roscoe Holcomb, and clawhammer [banjo playing]… I play banjo a lot too, three-finger Scruggs style banjo, and then the music of John Fahey sped up. I have a faster constitution. I like a ballad, too, but I have a certain urgency in my skull. It feels good to push yourself into uncomfortable territory. There’s nothing more thrilling than feeling like, “This train might just come off the rails right now, in front of these people.”

WEISS: You get that feeling while watching you perform—that you’re chugging ahead so fast and pressing up against the edge of something.

STELLING: Some of that might be my defense mechanism and my response; as comfortable as I am on stage, it’s never really the most comfortable. I’m pushing myself in other, slower directions. Some of the stuff that I’m writing is not necessarily so speedy; it’s a different kind of intense that I’m going for now, a more focused intensity. It’s good to look at what you’ve done and think, “What have I not done?” That’s why so many artists that have longer careers do change, and sometimes very abruptly, because if you’re not interested, how the hell is anybody else supposed to be? If you’re bored, everyone else is going to be too.

CHRISTOPHER PAUL STELLING BEGINS HIS NORTH AMERICAN HEADLINING TOUR TODAY, MAY 5. FOR DATES AND MORE INFORMATION, VISIT HIS WEBSITE.