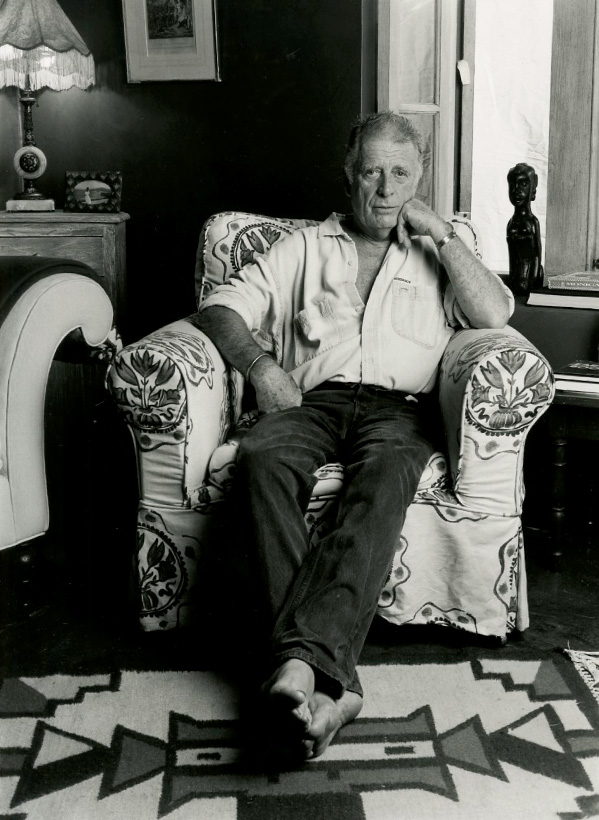

Chris Blackwell

“I’m not in the record business,” says Chris Blackwell, founder of the seminal label Island Records and nurturer of the careers of Steve Winwood, Cat Stevens, Bob Marley, U2, and others too numerous to name. “The business is not more important than the body of work that an artist will do,” he continues. “And I think that was the difference on how we approached having a record label.” Although, at 71, Blackwell now spends much of his time in his native Jamaica, he still has homes in England, Ireland, and New York. It was in his Manhattan apartment that we were having this discussion over coffee and toast (which Blackwell made himself) one Sunday morning, just before he was to board a plane to Miami. But despite his protestations, the facts are irrefutable: Blackwell wasn’t just in the record business—he transformed it. And it’s never been the same since.

Born into colonial aristocracy, Blackwell grew up in Jamaica while the country was still under British rule. He attended Harrow, the elite boarding school in England, for a period, and though he was not technically expelled, it was “suggested that Christopher might be happier elsewhere,” as Blackwell himself recalls. He began his working life back on the island, dabbling in various jobs—acting as an aide to the governor, teaching waterskiing, dipping into real estate, and even working as a location scout on the first James Bond film, Dr. No (1962), in which he also has a small cameo. Soon after, he got into music, buying records in New York and selling them to the DJs who ran sound-system dances (i.e., neighborhood lawn parties) back home. He eventually began recording and releasing records himself, creating the foundation of what was to become one of the most influential—and independent—labels of its time: Island Records. Although Blackwell started out working with Jamaican artists, his tastes were varied and eclectic, and Island would ultimately serve as the launching pad for a roster that included Traffic, Fairport Convention, Joe Cocker, and many others in the exploding British music scene of the ’60s and ’70s, and, later, acts such as U2, Melissa Etheridge, and PJ Harvey. But Island and Chris Blackwell will perhaps always be best known for introducing the world to Jamaican music and reggae—most famously, Marley, an artist whose influence and popularity continue to increase even years after his death.

I began working for Blackwell at Island Records after I was introduced to him by Michael Zilkha, whose Ze Records was distributed by Island (the label also gave starts to other independents such as Chrysalis, Beggars Banquet, and Virgin). Blackwell, who was never one for titles, referred to me as his “Minister without portfolio,” although later I added running the creative side of the U.S. label to my ambiguous duties. Blackwell sold Island to Polygram in 1989, and we continued to work together there until we left the corporate fold in 1997 to start Palm Pictures, an audiovisual company that is philosophically based on a concept similar to Island’s. Blackwell, who also ventured into the hotel business (and was partly responsible for the mid-’90s renaissance of Miami Beach), returned to Jamaica almost full-time, developing property on the island, including the GoldenEye resort, once the home of Ian Fleming, who found Blackwell his job on Dr. No.

This year, Island Records celebrates its 50th anniversary. And while Blackwell might protest that he is no longer excited by or even interested in the music business or that he doesn’t follow the entertainment world, he nonetheless interrupted this interview, excitedly, to make me watch a video of a song he thought was “incredible”—in this case, a performer named Mark Johnson, whose Playing For Change videos feature artists from around the world singing verses of Bob Marley songs. And it was.

HOOMAN MAJD: What kind of music did you listen to growing up in Jamaica?

CHRIS BLACKWELL: The early music you heard in Jamaica was kind of soppy. The best of it was country music, by people like Jim Reeves, because they were at least talented and they wrote good songs. But a lot of it was really corny stuff. The only thing you’d hear approaching jazz—and what I loved was jazz—was what Jamaicans called blues music. Now, their blues music wasn’t what the English called blues music. It was more like “Saturday Night Fish Fry” by Louis Jordan—it had this really pumping rhythm to it. Fats Domino had it. There was another guy from New Orleans called Smiley Lewis who had it, too. So that rhythm was something that people in Jamaica tried to emulate, but they got the accent of it wrong, and that’s how ska started—because the rhythm was on the off-beat instead of the on-beat.

MAJD: And you liked that kind of music when you were a kid?

BLACKWELL: I liked that, yeah, but at that time it was sort of . . . I was a teenager by the time that came around. So what I did was I’d go to some of these sound-system dances and I’d hear the music they were playing, and then I’d go to New York and I would buy records. I’d usually go when I had other things to do . . . I can’t remember what the hell I had to do in New York back then . . .

MAJD: I thought you were teaching waterskiing at the Half Moon Hotel in Montego Bay . . .

BLACKWELL: I was teaching waterskiing. I can’t remember why I went up to New York, although I remember a good few trips . . . But I do remember wandering along Sixth Avenue, which at the time was just two- or three-story buildings, and there were lots of little record stores. I remember the thing that was most influential to me was when I’d leaf through records, I’d see the labels on each of them, and I’d know what kind of music it would be. Laurie Records was a bit more pop. Cadence Records was an odd label because they had that record by The Chordettes, “Mr. Sandman,” which was a huge hit, and they also had The First Family record [the hit 1962 comedy album by Vaughn Meader, which parodied the Kennedys of Camelot]. Later, they had jazz artists like Don Shirley, who was Jamaican and who adopted an almost classical-music approach to jazz. But the label I’d really follow was Atlantic. When I saw any Atlantic record, I’d pick it up for sure. And if I ever played an Atlantic record and I didn’t like it, then I’d doubt my own taste because I had so much faith in the brand. So it was that kind of experience that made me feel like I wanted to have my own label. My way of translating the idea was that a label was like a group of artists, and everyone would be proud to be a part of it, because it was like they were all on the same wavelength.MAJD: So you’d find these records in New York and bring them back with you to Jamaica and then you’d scratch the labels off of them so nobody would know who made them or where they were from . . .

BLACKWELL: Yeah, they were records for the sound-system dances. I’d bring them back, but I’d scratch the names off. Obviously, today, it’s impossible to think that you wouldn’t know what a record was, because everything is so readily available. But in those days, that was not the case. So I would buy these records, scrape off the labels, and then sell them to these sound-system guys. Now, the sound-system guys were in the business of selling liquor, and what would happen was that people would have dances on their “lawns,” as they were called, which were far from lawns—they were sort of dirt patches. And they would book sound-system guys to perform. So these people would pay them, and they would get the gate money, but the sound-system guys would also bring the liquor. So it was like the biggest sound-system dance made the most money—just like today when a DJ spins.

MAJD: It’s who can bring in the biggest crowd.

BLACKWELL: And how did they get them there? By having the best records and stringing them together in a good way. So having a hot new record was very valuable—especially if you didn’t know where you were going to get it or what it was called.

MAJD: And you were the man who they had to come to.

BLACKWELL: Well, I went to them . . . I’d come back from the States with all of these records, and they’d say [in a Jamaican accent], “How much you want for dat tune?” So I knew all these guys when I started. And eventually I started recording with people in Jamaica. Laurel Aitken, Owen Grey, Wilfred Edwards—the first three records that I put out were by those guys, and each of them went to No. 1.

MAJD: In Jamaica?

BLACKWELL: Yes. And the reason they went to No. 1 is because Jamaicans were thrilled to hear Jamaicans singing. Now, Jamaicans still weren’t on the radio. They never went on the radio. Actually, Wilfred Edwards went on the radio because he sang a lot like Brook Benton, so he had a ballad that was very acceptable, and it was okay for the radio. But, soon after, a lot of people said, “You know, if this guy can make records, we could certainly make records.” So people like Coxsone Dodd, Duke Reid, King Edwards, Prince Buster—they started making records that were much funkier than mine. And as soon as these other records started to come out, they really took off. But what would happen is that they’d all do their own scratch-label thing. If they cut a great song, then they didn’t release it—you could only hear it at their sound system. And they’d do that for two or three months. Then they’d cut some soft wax, as it was called then, for other sound systems, maybe in London or in Montego Bay or something like that.

MAJD: London already had a big Jamaican community at that point?

BLACKWELL: England did, yes. And all of these guys had their own labels.

MAJD: And you called your label Island Records.

BLACKWELL: Well, I actually put a lot of the early ones out on a label called R&B. The first album I put out was Lance Hayward at the Half Moon [1959], and that was the first Island Records release. But I put out the others on R&B because I wanted a label that would identify itself with Jamaicans doing R&B music. I released a couple of Wilfred Edwards records, which were much more sort of smooth and pop-ish, on Island, but much later. But then 1962 came, and independence came to Jamaica, and at that time it was a joyous situation to get rid of all the Brits who fucked up everything—

MAJD: Right, under colonialism.

BLACKWELL: So, obviously, it made much better sense for me at that point to go to England, because I was selling more records there than I was in Jamaica anyhow—these other guys in Jamaica were making records that were much more in demand than the ones I was making, which had lost their luster in the domestic market. So I thought, Well, I’ll go to England and start Island Records there. All of these guys knew me from buying my records, so they basically gave me their records—particularly Leslie Kong [the late Chinese-Jamaican reggae producer]. He and his brothers invested 200 or 300 pounds and had like 20 percent of the records on our label. So that’s how Island went to England in 1962.

MAJD: And then you brought over Millie Small from Jamaica, and she had Island’s first true international hit with “My Boy Lollipop”?

BLACKWELL: Yes and no, because that record was not released by Island. It was actually released by Fontana Records [a subsidiary of Dutch Philips Records]. I licensed it to Philips because of something I’d learned from understanding the American independent record business, which was that if an independent label had a hit, then it was pretty much guaranteed that they’d be out of business, because most of the time, these small labels couldn’t collect that money from the stores fast enough to pay the pressing plant to make more records in order to meet the demand. When I heard “My Boy Lollipop,” I knew it was a hit. I also knew it was way beyond what Island could handle, plus it was much more slick than something that we would put out, so I licensed it to Philips. And then that record was indeed a huge hit everywhere in the world. I brought Millie over to England in ’63, the record came out in ’64, and I went with her on a world tour for six months in ’65. But just before I left to go on this tour, I had somebody tell me about this music in Birmingham that I should come and listen to, and it was there that I first saw Steve Winwood and The Spencer Davis Group.

MAJD: Now, how did you go from being a jazz lover and a connoisseur of Jamaican music to being into English blues and rock?

BLACKWELL: It was the voice of Steve Winwood—because I loved Ray Charles, and Steve Winwood was like Ray Charles on helium. Because it was the same phrasing, the same drive—it was like blues chords, but there was also just this incredible voice and musicianship. So I signed The Spencer Davis Group. And, at that time, we pretty much managed everyone that we signed, so we managed them. The rock scene was just sort of exploding at the time, with The Beatles and, after that, The Kinks, The Rolling Stones, and The Who. It all just changed. It was like the lights went on in England in the early ’60s, because up until then, nobody you heard on the radio had anything other than a BBC-type voice or accent. It was impossible for anybody with a Cockney accent or a Liverpool accent or a Manchester accent to get on the radio, much less have a decent job. But then, with those bands, that all started to change.

MAJD: I was recently at an event in Kentucky, and I met a British novelist, a former accountant who was the accountant for the Stones in the early ’60s. He said that Mick Jagger once came to him after he had already had a hit and asked him if he could help him get a job in the insurance business, because he didn’t think the music thing was going to last.

BLACKWELL: Well, Mick was also at the London School of Economics, so he was always sort of on course for a real career. He just played music because, like all of them, he was a fan of blues. I actually knew Brian Jones because he worked in a record store, and I tried to get him to take some of my records.

MAJD: Brian Jones?

BLACKWELL: Yes. But, you know, in those days the Jamaican records were only sold on the periphery of London, where the Jamaicans lived. In the beginning, we never sold any in the West End. The first one that started to sell in the West End was a song we had by Derek & Patsy called “Housewife’s Choice.” It wasn’t a particularly great song, but that was the name of a radio program on the BBC. So I guess that name triggered something. But other than that, I only sold records out of places like Brixton, Lewisham, Hackney, Harlesden, Willesden . . .

MAJD: So because you were on the ground in those areas, you had access to this incredible amount of talent that was coming up in England—and a lot of acts that the major labels were going after.

BLACKWELL: Well, the big labels weren’t going after them at first. The reason I was able to sign The Spencer Davis Group so early, when I had no experience other than with Millie—one would say that my main business at the time was still releasing Jamaican records—was because even though the majors owned 95 percent of the business, they weren’t sending anybody out anywhere to go sign anybody. People came to them, and their royalty rate was usually not more than five percent for the artist. When I met Cat Stevens in 1968 and I heard his songs—particularly “Father & Son”—I became very excited to sign him because I thought his work was so incredible. But he said he was signed to Decca. So I said, “Well, what’s your deal with Decca?” He told me, and I said, “I think I can match that.” [laughs] So there was nothing like the competitiveness that existed later.MAJD: As a label that was known for putting out Jamaican music, how did you get record stores to buy The Spencer Davis Group?

BLACKWELL: I licensed that record to Philips too. It was only when The Spencer Davis Group broke up, and Steve Winwood started with Traffic, that I put out his records on Island. That was in 1967, and it seemed like everything really blew up right around that time, because so many people in England were trying to make these basic, blues-based records, but people were also starting to write their own songs. In a sense, The Beatles sort of drove the whole thing, because they were a band that loved the blues and wrote their own songs, and their success kind of encouraged people. It’s like anything—you just need one example of success, and people say, “Boy, I think I could do that . . .” You know? So it was really The Beatles that drove the whole industry. They might actually be the reason why the whole world speaks English now. I really think so. I used to travel around Europe, because Millie was around the same time as The Beatles, and very few people spoke English when you were in France, Holland, Germany, Italy, Scandinavia . . .

MAJD: So John Lennon was right when he said that they were bigger than Jesus, because nobody speaks Aramaic now.

BLACKWELL: Well, the Rasta dem try. [both laugh]

MAJD: So between ’65 and ’75 you were just licensing your records in America?

BLACKWELL: I was touring a lot, because part of the deal I had with Winwood was that he would only tour if I toured with him. So I went everywhere that they did outside of England. I loved the touring because you could really feel the audience. You were much closer to everything.

MAJD: Well, you learned the business of touring, too, which was important for the kinds of acts that you signed subsequently, such as Bob Marley. Touring was crucial to Bob, who had a hard time getting on the radio.

BLACKWELL: Nobody was interested in playing Bob Marley on the radio. We had to tour him—that was the only way it could work.

MAJD: When Bob came to see you in England, did you already know him from Jamaica?

BLACKWELL: I didn’t know him.

MAJD: But you knew who he was, and he came to see you in your London office, and . . . Well, the story is famous: You gave him 4,000 pounds to go and make a record, not thinking that he’d ever show up again . . .

BLACKWELL: Well, I believed that he would.

MAJD: But nobody else at Island did.BLACKWELL: Nobody else in the world did. Bob Marley and The Wailers had a reputation for being total rebels and being sort of impossible to deal with. It was simply because, you know, they were being treated unfairly.

MAJD: So you gave Bob Marley the money, and then he went to Jamaica and recorded the songs that would become Catch a Fire [1973]. Then you went to Jamaica and heard it, is that correct?

BLACKWELL: I went about three months later. I went to where they had a little record store, because The Wailers had their own label, and they had been putting out their own records. Rita [Marley] was there . . .

MAJD: You’re going to see her in a few hours . . .

BLACKWELL: That’s right! And so I said, “I want to see the guys and hear what they’ve recorded. Have they recorded anything?” Because I was prepared for them to have done nothing. So they came around and picked me up and took me to the studio and played me some of the songs. The first one I heard was “Slave Driver,” and I remember it particularly because, firstly, I was excited that they had recorded anything. So I was really encouraged. It had this great kind of bass line. The second line of the song says “catch a fire,” and, you know, I remember thinking right there, Wow, if this record is good, then that’s the title of the album. After that, they played “Concrete Jungle,” which was the most complex reggae song I had ever heard. And then they played me another ballad-y song, and it was nice, but it wasn’t really what I was looking for, because I was looking for rebel, militant music, since the whole thing was coming off the momentum of The Harder They Come [1972], and I wanted that spirit to come alive. Initially I was figuring out that that was what to do with Jimmy Cliff, but Jimmy Cliff left about a week before I got there, and then Bob walked in, and he’s the real thing. So I said, “I think we should put that song on the record later,” and then, you know, when it was finished, I told them how great I thought it was. And then Bob came to England because I wanted to work on the record to make it more palatable for the rock audience.

MAJD: At that point you’d been dealing with that audience for a while.

BLACKWELL: Yes. And I knew we could pull them in, but reggae in England at that point was known as novelty music. Every year, there’d be two or three hits, like “Long Shot Kick De Bucket” [the 1969 song by The Pioneers], but they were like novelty tunes. At that time, reggae wasn’t considered serious music, whereas rock music had been considered serious for some time. Jimi Hendrix was a model, in a sense, because I felt like Bob could be that big. And so I worked on Catch a Fire. I moved things around. I had rock guitar, synthesizers, and expanded into solos, because reggae never had solos—although ska did—so I put that element back into the music. In fact, if you listen to the work that Bob did on Island, from Catch a Fire up until the last record he made [Uprising, 1980], the first one is much more polished than the last one. But I needed to polish it to bring in the rock audience and to get them accepted as a black rock group—that’s how I was positioning things.

MAJD: So the way you marketed Catch a Fire wasas a rock record?

BLACKWELL: Completely as a rock record. The idea of the cover came from the art director at Capitol Records in America, because I had made a deal for Island in 1970 with Capitol. It was that guy who came up with the idea of the lighter . . . Ah, what’s it called?

MAJD: The Zippo.

BLACKWELL: The Zippo.

MAJD: The sleeve opened like a Zippo lighter to reveal the album. It’s an iconic album cover. If you still have a copy of that, it goes for a lot of money . . . [The original version of the Catch a Fire sleeve only came with the first 20,000 pressings of the album. After it was discovered that producing more would be too expensive, alternate cover art was selected.]

BLACKWELL: No, I don’t have one. I wish I did.

MAJD: Amazingly, Catch a Fire wasn’t really a hit initially in terms of sales. But it certainly made a lot of noise.

BLACKWELL: Yeah, Catch a Fire only sold about 14,000 copies in its first year, but it got great reviews. It made noise, which was basically the main thing we wanted to do with it anyhow. I’ve always looked at it this way: I’m in the career business—I’m in the artists business, with the records being the milestones. So I’m not in the record business, per se.

MAJD: So you had this huge success with Bob. And, of course, you’ve also had success with some other Jamaican records . . .

BLACKWELL: Lots. Third World, Burning Spear, Toots and The Maytals, Steel Pulse . . .

MAJD: But none of them enjoyed quite the success or the acclaim that Bob Marley did. Was there any jealousy in the Jamaican music industry? Was it difficult for you, as a Jamaican, going back and forth between England, America, and Jamaica?

BLACKWELL: Well, it’s hard, from a developed-world point of view, to see it from the Jamaican point of view. Because from the Jamaican point of view, I was the one who made it all happen.

MAJD: You’re the white Jamaican who stepped in with all the contacts and the experience . . .

BLACKWELL: Right. And that still existed, as much as I would try to say to people, “I can help, but it all starts from you. I’m not writing the songs . . .” So, for a while, I stopped signing Jamaican artists, because if somebody signed with Island, they’d feel like, “Well, that’s it. Now our record is going to be a huge hit automatically.” And, of course, the worst thing is to disappoint people . . .

MAJD: Especially in a small community like Jamaica.

BLACKWELL: Yes. But the Jamaican people needed to see how the world embraced Bob Marley. In Jamaica, a lot of the powers-that-be are not all that comfortable with Bob Marley being the image of Jamaica and being the reason that people even really know where Jamaica is. They don’t feel too good about it. As far as they’re concerned, he’s this guy from the street.

MAJD: And then you moved on . . . And in 1980 you signed U2. Of course, that was big.

BLACKWELL: I’ll tell you what happened. First of all, after Bob, somebody who I felt could have been a big star was Jacob Miller. Bob basically became a rock star in Jamaican music, and Jacob, I felt, could have done the same. He was a big guy, but an incredible personality. Incredible. I mean, I have a picture of Bob and Jacob and myself standing in front of a plane, and you look at it, and you would say that Jacob is the biggest star there without any question. He just had that presence. But then he was killed in a car crash, and things ended before they began. And then the other people who I thought were the epitome of what I believed in were Black Uhuru—what an incredible name . . . Their music sounded like Black Uhuru, they looked like Black Uhuru, they even won a Grammy. But they said, “What is Grammy? Wha’ dat?” And then they broke up. So, after all that, I thought, “Just forget about it.” But I had spent no time on U2. I just saw them, I liked them a lot, I believed in them, and I signed them to the company. But I did not have any influence on them at all. I had nothing to do with their recordings, their graphics, their touring. They did everything themselves. What I did for U2 was to give them the platform of Island Records, because I said to the company, “These guys are in charge.” That’s why when we were working on their Pop [1997] record in the late ’90s [which was one of U2’s less successful albums, both critically and commercially], there was no model for anybody to say to them, “Hold on. This is a mess . . .” Because nothing like that ever happened with them before. Now, of course, they are huge, but they’d always been in charge of their own careers . . . But I think, honestly, after Bob passed away, I lost a lot of interest. There was something so exciting about Bob Marley, because you knew it wasn’t just about the charts. It was literally about changing the world again. And so it was incredibly exciting to play a part in that, and see that happening, and to help guide it. But after Bob, things sort of shifted for me. I was spending more time at Compass Point Studios, and working with Grace [Jones], which was fun. And then, you know, video started to emerge in the early ’80s . . .

MAJD: When, of course, you had a surprise hit with Robert Palmer and “Addicted to Love.” I remember you telling me that Island was an independent label and that you owned it and there were ups and downs financially, but you said that you put all of Island Records’ money behind the video for that song.

BLACKWELL: The person I picked to direct that video was Terry Donovan, who was the greatest fashion photographer for women, and, you know, he’d make women look unbelievable. He just had it. And Robert, who was a very good-looking guy, somehow only photographed really well if there was a woman in the picture. I don’t know what it was, but suddenly he sort of came to life. So I rang Terry Donovan and asked him if he’d do a video. He said, “Well, I don’t do too much video.” And I said, “I’ll send over the song.” So I sent over the song, and he rang me back and said, “I like the song, and I’ve got an idea for it. I’ve got these girls, and they’re going to be, like, the band, and he’s going to sing in front of them.” And I thought the idea sounded really corny. I thought, Oh, my God, this could be a disaster. But I had a lot of confidence in Terry, so I said okay. Robert went and did it and when he came back—because I was living in Nassau then, as was Robert—I said, “How did it go?” And he said, “I think it went really well.” I said “Really? It didn’t look corny?” And he said, “No, they looked great.” So, boom, flash-forward a couple of weeks, and a tape arrives. I call Robert and say, “The tape has arrived. Let’s go and watch it.” We turned it on, and we’re watching and we’re like, “Fuck, this is unbelievable.” So I rang the company and said, “Whatever we’ve got, let’s roll the dice.”

MAJD: [laughs] It was a gamble. But it was one of those bets that paid off in a big way.

BLACKWELL: Big time. And that’s when I thought, You know, the future of everything is going to be a merging of music and film, because the videomakers of today are going to be the filmmakers of tomorrow, so we should really be in the film business as well as the music business—sort of merge them together. That was my thinking.

MAJD: In 1989 you wound up selling Island to Polygram Records. What led up to that?

BLACKWELL: I sold Island because it had gotten too corporate. It was just too many people . . .

MAJD: Our staff at that point was, I think, 120 people in America alone . . .

BLACKWELL: Right. And that wasn’t my thing. When you get big, you can’t keep the same kind of label identity, because you have to have lots of different people doing things. And when you have lots of people doing things, naturally they have their own tastes. At that point, I was 52—and the music business is really about younger people—so I decided I was going to move back to Jamaica as a sort of base, and focus on the hotel business.

MAJD: Do you follow the contemporary music scene in Jamaica at all now?

BLACKWELL: I don’t. Now and then I hear a record that I think is really great . . . Most of them are sort of mash-up-type records, which are incredibly creative, but it’s almost impossible to administer the copyrights for them. But a lot of those records do just go off somewhere you don’t expect and have that sort of excitement to them.

MAJD: Do you miss the music business at all?

BLACKWELL: Well, there isn’t really a music business right now. If I were in my twenties, I think this would be an exciting time. Somebody right now could build another Island Records. The music business is at the point where it needs to be reinvented again. When I started, Decca and EMI had 95 percent of the business, Philips had 4 percent, and the final 1 percent was split among all the little independents. We’re in a situation sort of like that again now, except back when I was starting, the cost of entry was high, because there was no way to get around distribution. But I feel proud that Island broke down a lot of those barriers—and broke the system, really. The majors are still clinging on desperately by their fingernails. The people who own the big labels today do not know the music business, and the people who are running them don’t know it, either. Ninety percent of them should be fired. But these labels have incredible catalogues, and that’s what keeps them all-powerful. They own all this great music. So they should just consolidate and manage their catalogues digitally and then provide a platform for new music to be heard—because that’s all a record company really ever was anyhow.

MAJD: If you still owned Island Records, is there anything that you would want to do to celebrate its 50th anniversary?

BLACKWELL: Well, what I would love to do would be to have a free concert in Kingston. I’d love to do a big show in Jamaica that everybody could come to . . .

MAJD: Like a big thank-you to the island where it all started.

BLACKWELL: It could only really happen there. And it would be great, of course, if U2 could be involved . . . So we’ll see. But some of the old acts are still around and are as good as ever. Toots, you wouldn’t believe it—the energy is the same, the voice is the same. Jimmy Cliff too.

MAJD: Cat Stevens still has a great voice.

BLACKWELL: He might be doing something for Island’s 50th in London.

MAJD: Oh, he might?

BLACKWELL: Yeah. And he might be doing it as Cat Stevens.

MAJD: I guess the Yusuf Islam thing didn’t work out. [laughs]

BLACKWELL: No. When he played me his record two or three years ago, I thought about how good it was, and that it could do something. So I asked him under what name he wanted to release it, and he said Yusuf Islam. I told him that I didn’t think there was any chance to sell the record under that name. And he said, “What name do you think I could use?” And I said, “Well, Cat Stevens.” [Majd laughs] My logic for it was that his real name was Steven Georgiou, and he used Cat Stevens as his stage name, so if he changed from his previous real name to his new real name, why not keep his stage name? So that was the argument.

MAJD: At the time it didn’t work.

BLACKWELL: No, it didn’t fly. He said it would look like he was turning his back—

MAJD: On Islam . . . which he hasn’t, obviously.

BLACKWELL: No, he absolutely hasn’t.

MAJD: And you have to give him credit for that.

BLACKWELL: But I think he’s moved away from being very fundamental. He’s fantastic, though. Cat Stevens is truly one of the greats. It’s amazing in the sensethat the three biggest acts we had were Cat Stevens, Bob Marley, and U2—all very religious.

MAJD: Well, I hope that concert comes together.

BLACKWELL: I hope it does, too. It would draw a lot of people to Jamaica.

MAJD: It’s interesting because you’re promoting Jamaica now, and not musicians, but you’ve always liked to be in the background. You’ve never wanted to be onstage with anyone. There are even very few photographs of you with any of the artists whose careers you’ve helped launch.

BLACKWELL: Because I never liked the whole thing about pictures with the artists. I mean, you look back at an Elvis Presley record, and you don’t see any producer credits, because the audience is not supposed to know about the producer credit. They’re not supposed to think about that. The whole thing is supposed to be the act. It’s all about the act.

Hooman Majd is a New York–based writer and contributing editor at Interview. His book The Ayatollah Begs to Differ was published by Doubleday in the fall of 2008.