The Truth About Spandau Ballet

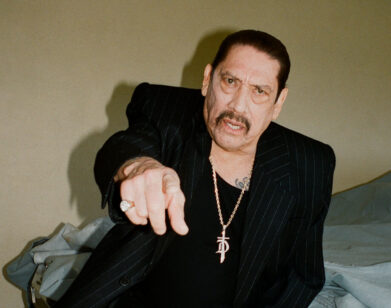

ABOVE: SPANDAU BALLET. PHOTO COURTESY OF SPANDAU BALLET.

Spandau Ballet are waiting in the funky lobby of the Ludlow Hotel on the Lower East Side, a team of five good-looking, nattily-attired men, with George Hencken, the director of their new documentary, Soul Boys of the Western World. Hencken is a striking blonde woman.

The film documents the British band’s mercurial career through its formation in 1976 to its breakup in 1990 and subsequent reunion in 2009. It is no mere biopic; rather, the focus is on the legacy left by Spandau Ballet’s unique blend of glam-rock and punk fashion as “New Romantics.” Over the course of their career, members Tony Hadley, Steven Norman, John Keeble, and Gary and Martin Kemp have sold more than 25 million albums. The band’s name comes from graffiti written on the wall of a nightclub bathroom in Berlin. It refers to Spandau Prison, a former Nazi prison in which war criminals were held after the end of World War II.

GERRY VISCO: Hi, I work for Interview magazine.

GARY KEMP: No wonder you look so good.

VISCO: The funny thing is, I don’t know who is older, you or me, but I’m from a generation where I listened to your music in the day. Just so you know.

GARY KEMP: You didn’t come to the underground club in 1981 to see us play when you first arrived?

VISCO: No, but I wish I did!

GARY KEMP: The photograph is the poster of the movie. Did you see that? We’re all lined up in the street in New York. Did you see that footage when we first arrive in New York?

VISCO: Yes, it’s beautiful. I guess you liked New York then?

GARY KEMP: Well, you know that New York was virtually the only other cool place besides London.

VISCO: I suppose in terms of nightlife and fun. I always regret not having gone to the Blitz club in London. That must have been fabulous. New York nightlife hostess Susanne Bartsch told me she was a “Blitz Kid” back in the day. And the outfits were incredible.

GARY KEMP: Yes, you should have Susanne do our after party here in New York! We knew her then. It’s a shame there wasn’t more footage of the Blitz club fashions.

GEORGE HENCKEN: The Blitz club as it appears in the film is basically a couple of frames when it wasn’t the Blitz club night because there just weren’t any video cameras around at the time and nobody was going to take a Super 8 camera around to a little dark club. We were trying to re-create the Blitz out of little bits of music.

MARTIN KEMP: I’m surprised British filmmaker John Maybury didn’t film of it any because he was a Blitz Kid.

HENCKEN: It is really surprising.

MARTIN KEMP: Perhaps it will surface somewhere.

HENCKEN: I don’t know if it will though because people have been looking for a really long time.

MARTIN KEMP: I mean think about it, who was ever going to film anyone at the Blitz? You wouldn’t have wanted to be filmed.

HENCKEN: You didn’t want to look at other people—you wanted other people to look at you.

VISCO: What I was curious about was, how did you get all that footage? It’s amazing. I’m not talking about the Blitz; I’m talking about everything. You even had some film footage of yourselves as children, right?

HENCKEN: There wasn’t footage per se. There were photographs and home movies of the boys as kids.

VISCO: That’s amazing too because not everybody did have home movies in those days.

HENCKEN: This is very true.

GARY KEMP: It wasn’t us that filmed back then. It was our parents. They filmed so they could show the family later on.

HENCKEN: John had demo tapes, which meant I could put John’s audio tapes together with Steve’s Dad’s footage.

GARY KEMP: There’s a team between George Hencken and Kate Griffiths who is collating, what’s her official title?

HENCKEN: She’s the archive producer. Basically, most of the films I’ve made in the last few years have had a lot of archiving. I love using archive, which is why these guys thought I might be able to do this. And the deal is that basically there are different archives. There are archives all over the world. Each TV station will have it’s own archive and you’ll get your archive producer. She got all the stuff together but it was a big dragnet and she gave it to me in a lump. My job was to go through all of it. I watched I think 450 hours worth of Spandau Ballet.

GARY KEMP: It could have gone anywhere. Obviously there was an arc to our story, looking for those little nuances that make the drama happen. That was really in our hands to try and filter through the archive.

VISCO: Did you write something out, a structure?

HENCKEN: When they asked me to do it, the only way I could was to say, “You have to let me do it the way I want to do it. You can’t tell me how you want to tell your story.”

VISCO: If there was negative material, how did they handle it?

HENCKEN: There’s a lot of stuff in the film that’s quite close to the bone. But these guys are big enough to take it.

GARY KEMP: If you’re confident about where you are now in your life then you can handle it. For as much as my issues in the film with myself, I look at a boy who’s got a lot of drive. It works either way.

VISCO: Well it’s a saga of your relationship and the band and the music. What I found interesting is that it’s a document of the times.

GARY KEMP: We thought we were living in the future in 1980. You know, the pre-internet world is such a different time

HENCKEN: The other thing you see in the film is the huge contrast between the 1970s and the 1980—that change that happened when everything was brown and orange and avocado green, and then all of a sudden it was all pink and electric blue and acid yellow.

MARTIN KEMP: I love those shots when people are posing at home and they’ve got this otherworldly gear on and yet there’s your mum and dad’s furniture in the background. It looks really weird being on the tube dressed like that. What’s funny is even the Super 8 quality is avocado green. I suppose what was equivalent in the 1980s to the internet was MTV and cable television because that was the beginning of globalization of youth culture. And when we first came to America in May 1981, we were totally aliens. We brought over, en masse, with the Blitz and a lot of kids who were designers at [Central] St. Martin’s. We did a fashion show before the gig at the Underground. We brought over a DJ and the whole scene.

VISCO: Did you guys think you were cooler than us Americans?

GARY KEMP: Absolutely we did, sorry.

VISCO: Did anyone tell you that you were wrong?

GARY KEMP: Well, we didn’t see you.

VISCO: I was going to the Mudd Club, but that was over by then.

GARY KEMP: It’s interesting because CBGB’s, the Mudd Club, that period of life, of youth culture, was always about getting out on the street, finding a venue. The venue was the focus; you wore a uniform and that’s where you gathered and found like-minded people. The need to do that is much less now because you can do it on your phone. We came to New York because we knew there’d be like-minded people here.

VISCO: Of course, so the audience was cool?

GARY KEMP: Absolutely.

VISCO: Punk performer Richard Hell maintains he invented punk fashion, which kind of went back and forth, influences between London and New York.

GARY KEMP: Iggy Pop was the prototype.

VISCO: Hell invented the safety pins and the torn up stuff.

GARY KEMP: You know the hair—that chopped up hair—was the first Ziggy Stardust look with David Bowie. Richard Hell was only copying and Johnny Rotten was copying Bowie as well.

VISCO: So, you were influenced by them when you were just starting in the late 1970s? Did you start going out to the clubs?

GARY KEMP: Billy’s was the pre-curser to the Blitz. There was one night where Rusty and then Steve Strange took it over and the whole scene started. It was a cool Bowie night in the beginning. Punk was definitely a huge influence on all of us. It’s why we formed the band. We were dressing up the way we were in 1978 and we went to Soho and we were freaks. Now you go to Soho and everyone’s like that.

VISCO: I know the whole thing has changed. But you guys lived in Islington?

TONY HADLEY: Yes, we were working class people.

VISCO: So when you started out, you were like, “Oh my god, who the hell are those guys?”

MARTIN KEMP: When we were first dressing up we were hanging out with Boy George and people like that.

HENCKEN: When they started doing gigs outside of London, there was a gig they did in Birmingham at the Botanical Gardens in 1980 and Steve Dagger, the band’s manager, told me about this gig and how it had been this incredible thing where they arrived in Birmingham and nobody could believe what they were seeing. Then I met a friend of mine, who happened to have been at that gig and he said, “It changed my life.” The gig was in this bizarre place—not a usual venue—and these guys had brought their whole cohorts of Blitz kids down to Birmingham with them. And here’s my friend Jamie Rhodes, a little black guy in Birmingham, and he said they looked like nothing you’d ever seen before. Everybody who left that gig that night said that it changed everything about the way they lived.

VISCO: When you first started out were you able to make a living from the band or did you have day jobs?

HADLEY: We had decent jobs, but it was always something taking our attention when we should have been spending time creating. We used to hand out magazines on the corner and we’d do it together and one time we were handing them out and we were in it so we said, “I guess we better stop.”

VISCO: When you guys got back together had you been in contact?

GARY KEMP: We didn’t speak to each other for nearly 19 years. The thing about George Hencken with the film is that she picked up on the most important part of our story and that is our journey as friends, and the fallout.

VISCO: So this is going to stick you think?

GARY KEMP: Yeah, for sure.

VISCO: But you’re still able to tour and that’s no problem?

GARY KEMP: Yeah. We’ve still got energy. We’ve been busy. This is the last day of a two-week whirlwind promo tour.

VISCO: Were drugs an issue for Spandau Ballet?

GARY KEMP: No we never had a problem with it.

VISCO: Did you guys drink a lot back in the day?

GARY KEMP: Well, no one was a teetotaler!

VISCO: But are a lot of your friends gone?

MARTIN KEMP: They’re not gone necessarily because of drugs but with age.

VISCO: As the film was going on, did you guys have to put a lot of input?

GARY KEMP: The production was tough, gathering all the material and offering it to George.

HENCKEN: The thing is, as a filmmaker the last thing you want to do is have the subjects of your film have any input into what you’re doing when you’re trying to figure out what the story is. The tricky thing with the Blitz stuff was that there was no footage of the Blitz. I had to make it, cobble it together, make it out of stuff and cheat it basically. I really needed it to be right because a club you’ve spent your formative years in is a sacred, precious thing and you do not want anybody to misrepresent it. So if I’d gotten that wrong the whole thing would have lost all credibility. It was having Gary and Steve Dagger come in and say, “Yeah, that’s right,” or “No, that’s wrong.” Steve Dagger one time said the stuff I had, it was the wrong night and it didn’t look right and that’s why I needed Gary and Steve and these guys who’d actually been there. And one of the really useful things was finding photographs by a woman called Nicola Tyson. She’d taken photographs in Billy’s. I was googling, and up came Nicola Tyson. She did this exhibition and there’s all these pictures and it’s all the guys, Boy George as a tiny little infant child.

SOUL BOYS OF THE WESTERN WORLD OPENS TONIGHT, APRIL 27, AT THE IFC CENTER IN NEW YORK, AND WILL EXPAND TO L.A. AND VOD ON MAY 8. SPANDAU BALLET WILL PERFORM IN NEW YORK THIS SATURDAY, MAY 2, AT THE BEACON THEATER IN NEW YORK AND ON MAY 3 IN WESTBURY, NEW YORK. FOR MORE INFORMATION, VISIT THE BAND’S WEBSITE.