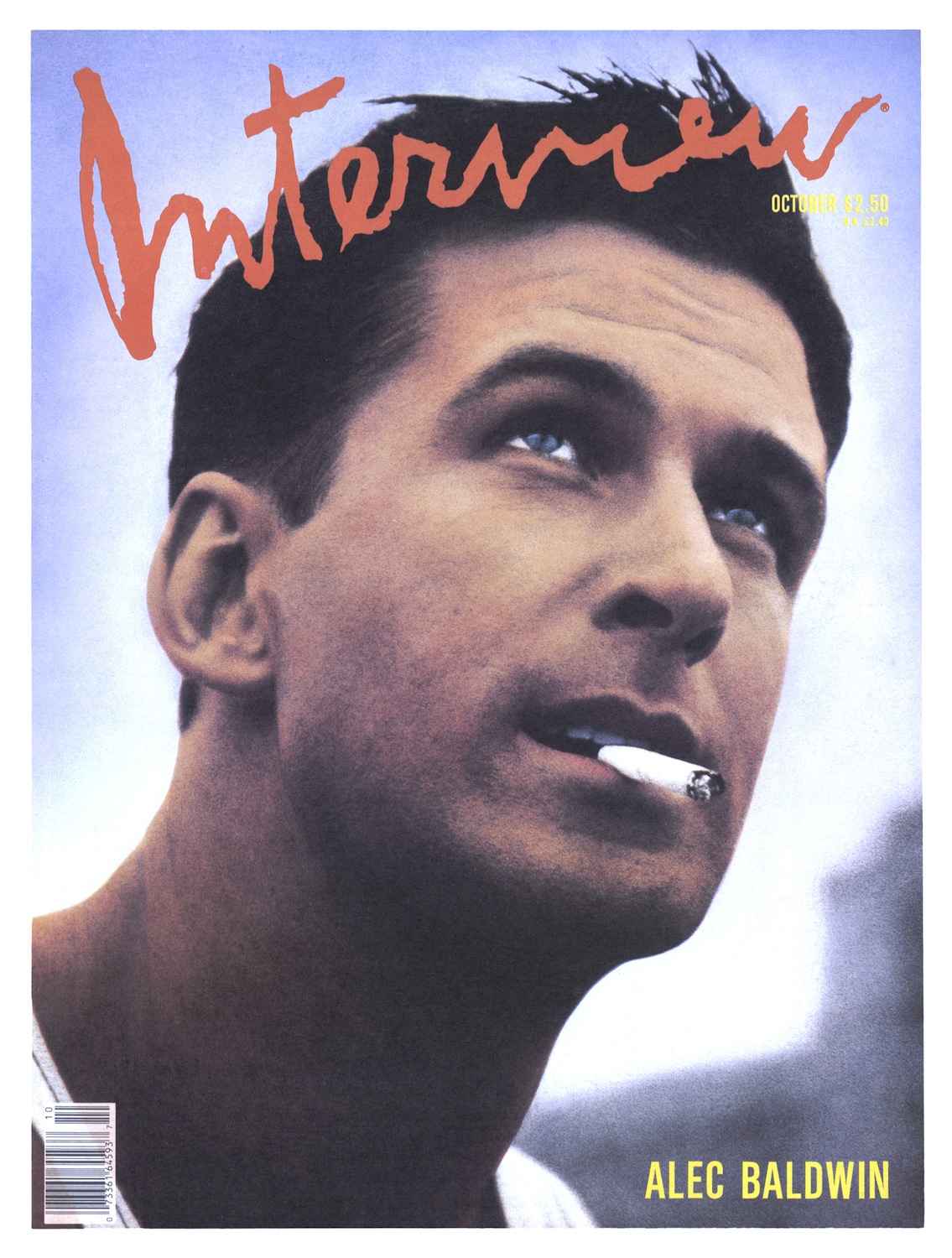

New Again: Alec Baldwin

After taking a turn as a Sunset Strip club owner in last week’s screen adaptation of hair-metal musical Rock of Ages, Alec Baldwin will appear in Woody Allen‘s latest European ode, To Rome With Love, to be released this Friday. The newly engaged, paparazzi-sparring actor and Words With Friends enthusiast is currently attached to another project with Allen currently in pre-production, and is set to return for the upcoming, final season of 30 Rock on NBC.

In the late 1980s, Baldwin was coming into his own in Hollywood with roles in She’s Having a Baby, Beetlejuice, Working Girl, and Married to the Mob. For our October 1989 issue, journalist Charles Kaiser interviewed Baldwin just as he was making the jump from supporting actor to leading man. Just weeks after shooting The Hunt for Red October alongside Sean Connery, Baldwin chatted with Kaiser in New York over Chinese food, speaking candidly on subjects ranging from his days as a waiter at Studio 54, attending Robert Kennedy’s funeral, and his immense dislike of reporters (and interviews, for that matter).

Long before Jack Donaghy, his politically divisive Twitter account, mayoral ambitions, Oscar-hosting duties, and Capital One endorsements, Baldwin was brash, irreverent, and prone to impressions. Here, he takes on his early days in New York, soap operas, Henry Miller, and getting into politics.

Baldwin on the Brink

by Charles Kaiser

After a series of notable supporting roles, Alec Baldwin is making the move to leading man in The Hunt for Red October. Charles Kaiser found the man from Massapequa decompressing in Manhattan.

When Alec Baldwin appears at the door to be interviewed, he looks appropriately casual for a Saturday afternoon in Manhattan: black T-shirt, khaki pants, and the inevitable white leather sneakers. Baldwin is the oldest son (and the second-oldest child) in a family of six children. Like Christine (George, at the time) Jorgensen and Ron Kovic, the Baldwins are from Massapequa, Long Island, and because of the latter connection all three of Alec’s brothers got parts in Oliver Stone’s forthcoming film version of Born on the Fourth of July. His brother Stephen is also appearing in a new series on ABC, and his brother Billy will play Robert Chambers in The Preppy Murder Trial.

Now 31, Baldwin has been busier than almost any other young actor for the past two years, with large but never starring roles in seven films: She’s Having a Baby, Beetlejuice, Married to the Mob, Talk Radio, Working Girl, Miami Blues, and Great Balls of Fire. Despite an acknowledged prejudice against the Fourth Estate, he seemed quite cheerful when we met and talked over Chinese food, probably because he had just finished shooting the first film in which he is the star—The Hunt For Red October, with Sean Connery. He was also pleased because he was about to leave for Paris to play Henry Miller in Phillip Kaufman’s movie, Henry and June.

CHARLES KAISER: How did you start acting?

ALEC BALDWIN: Visiting a friend at NYU, to give you the short version.

KAISER: I can take the medium version too, you know.

BALDWIN: I was in college in Washington, D.C. I did three years full-time. I did all my requirements and my senior year was really a gut year. And I said, law school will always be there. I was in no hurry to get right into that.

KAISER: Was that the plan?

BALDWIN: Yeah, law school was it.

KAISER: So that you could grow up and become president someday?

BALDWIN: I wanted to be president of the United States. I really did. The older I get, the less preposterous the idea seems. But I have always wanted to try acting. I had acted in high school a couple of times. Then a friend introduced me to people at the NYU Drama School, and they described a program where you studied with Lee Strasberg through NYU and took your academic classes at NYU. And, of course, growing up on Long Island, I’d always wanted to live in Manhattan. So I figured out a way that I could afford to come to New York and go to school. When I told my parents, “I’m going to be an actor,” they screamed and wept and freaked out. I went to NYU for a year. And they wanted me to go for a fifth year to get my two degrees, because I was working on a double major. I was going to finish my poli-sci degree. But the summer between that fourth and fifth year—I really wanted my degree—I got offered a daytime TV show. And I was broke then—I was the kind of guy who would steal bowling shoes from a bowling alley just to have a pair of shoes. I was so desperate.

KAISER: What year are we in?

BALDWIN: It’s the summer of 1980 and I’m living in a five-bedroom apartment up on 91st and Madison; the owner, a professor at NYU, was never there. She was an anthropologist, and she went away to Africa and said, “You can have a room in my house with my children. My five children. Who are all ‘at’ university. They will be returning home to New York for the summer, so I must ask that you confine yourself to your room and your room only. And the baaaathroom, of course.” And she gave me this little room, this little closet. I think it was a closet in their house.

KAISER: Were you paying for this privilege?

BALDWIN: Yeah. I paid 150 bucks a month—which is not bad, but I was poor. I’m allergic to cats, and the woman had like 16 fuckin’ cats in this house! I had no air-conditioning, so I slept on the fire escape above the Jackson Hole hamburger place. I was miserable, I was lonely. And then daytime TV came along and said, “We’re gonna pay you.” I think it was $400 a day to do this soap opera. Four hundred dollars a day! I thought I was Rockefeller.

KAISER: Which soap opera?

BALDWIN: The Doctors. I played Billy Aldrich.

KAISER: And what were Billy’s salient characteristics?

BALDWIN: Well, as I’m fond of saying, the key words with Billy was “relentless.” Billy was relentlessly evil, relentlessly greedy, relentlessly horny. He had a hard-on for life, Billy, He was a baad, bad boy. Billy—an actor playing me in a younger incarnation—had knocked up his girlfriend and fled town.

KAISER: You inherited the character from another actor?

BALDWIN: I came back as Billy the young man, as opposed to as a boy. Older, but no less evil.

KAISER: You looked the part. How much acting had you done at this point?

BALDWIN: Pretty much dick. Midsummer Night’s Dream, for Strasberg. Jonathan Ringkamp, who has passed away, belonged to an order of Franciscan brothers in Brooklyn. He taught at Strasberg and directed this production of Midsummer Night’s Dream.

KAISER: Did you have any other jobs?

BALDWIN: The year I switched to NYU, I was a waiter at Studio 54 for two months.

KAISER: What was that like? You got hit on by customers of both sexes all the time?

BALDWIN: Usually men. Gay men would go up to the balcony and fondle one another. Usually couples. Very distinguished, wealthy, well-dressed. Well-heeled gay men would go up to the balcony and “discuss things.” And they’d ask your boy here to go downstairs and quote-unquote “fetch them” a pack of cigarettes. Cigarettes at Studio 54 were probably like eight dollars. And they’d say, “Well, keep the change.” I was a very popular “cigarette snatcher” in the balcony. I was the Rick Blaine of well-heeled homosexual balcony dwellers at Studio 54. This was the fall of ’79, and then the spring term of ’80 I drove a limo. I sold shirts at BFO on lower Fifth Avenue. I was a waiter in a restaurant. I had 60 jobs.

KAISER: So how did you get the soap opera?

BALDWIN: I was waiting tables that summer at a health club atop an apartment complex in the Lincoln Center area. They had a pool on the roof and a café. I was a waiter by day and a lifeguard by night. And someone said, “I think you should meet my friend who casts soaps.”

KAISER: Did you intend to be an actor at this point?

BALDWIN: No, I was going to go back to school for that final year. I was trying to make as much money as I could. I didn’t want to go out to Long Island. I used to be a lifeguard on Long Island beaches. I didn’t want to leave the city. I was still totally jonesed-out on New York and loved the city. What happened was they gave me a full scholarship tot return to NYU. I was very flattered, and really psyched. But anyway, someone said to me, “You should meet this woman from NBC, Susan Scudder.” Great lady. She now works for Stephen J. Cannell.

KAISER: What was The Doctors like?

BALDWIN: Soaps are the best. They really are. If you can do a soap, well, you can do anything. You have to learn pages of dialogue very quickly. It was very intense. Making choices. Getting along with people. As time went on, my character became more and more important. Eventually it was one of the most important in the show. Our show was one of the last of those old dinosaur shows. You know, soaps went through a transformation. Soaps were like radio—they were for housewives, who wouldn’t always be watching the screen. They’d be cleaning and ironing, so you always had to say, [in a soap-opera voice] “But Bob! I told you that if you left me I would inform Mary of the documents! And your relationship with Bill!” Then The Young and the Restless came along and changed everything. Young people, sex up the yin-yang, bad acting—all that stuff.

KAISER: How long did you do the soap?

BALDWIN: Two and a half years. They got me for peanuts because I was nobody.

KAISER: Did you get an agent while you were doing it?

BALDWIN: Yeah. He’s been my agent ever since, and he’s the greatest agent in all of show business—Michael Bloom. It all started with walking into Michael’s office and just being ashamed. He was representing people like Roxanne Hart, Roberta Maxwell, Jack Weatherall. And people who were doing a lot of stage work—really big names in regional theater. Through all those people, I got to Williamstown for the first time. My whole introduction to this business was: If you don’t do something in the theater regularly, you’re nothing, you’re a shit. The minute I get the chance, I go back and do that, because it really does help you. Psychologically. Making movies is very boring overall. In the theater you act more of the time. In the movies you get to act maybe 20 or 30 minutes of the day. I love acting in movies. It’s just different. I did Loot on Broadway at the Music Box Theatre. I worship Orton.

KAISER: When did you move to Hollywood?

BALDWIN: I went to LA after The Doctors. I got a role in a pilot. Then I came back home for a couple of months because my father died. I was very, very close to my father. We buried him, went through all that. The pilot got picked up, and I moved to LA permanently.

KAISER: Where did you live?

BALDWIN: First I lived in West Hollywood for a couple of months, around the corner from Tower Records, north of Sunset. Then I moved to the apartment that I kept for about six years. I lived on the Boardwalk in Venice because it was the most like New York. I had a Karmann Ghia Volkswagen convertible that I drove cross-country in ’83 with a friend. Later I was in a head-on collision and hurt my neck and back pretty badly. I had to buy a new car, so I bought a Lincoln-Mercury. And I just bought a new Mustang. I hate buying foreign cars. I feel like I’m betraying the starving UAW workers in Tennessee or something.

KAISER: So then you started doing what—Knots Landing at this point?

BALDWIN: Shelly Hack and I and an actor named Jim Metzler, who’s a friend of mine, did a medical series, Cutter to Houston, which could have been interesting if they had stuck to what they said they were going to do. It ran for only seven episodes.

KAISER: What network?

BALDWIN: CBS. I always liked working for CBS. They’re very decent.

KAISER: You’re saying that with a straight face!

BALDWIN: Well, I mean decent for actors. I don’t want to get into this, because it’s like bashing people, but there’s one network in particular where they just hate actors. They beat you down, they hire awful producers, and the actors are treated like scum. This network is doing very well right now, but every show that has become successful for them in recent times has been independently produced. The thing that’s made them number one has nothing to do with them. Every time I’ve worked for them it’s been a fucking nightmare. After Cutter to Houston I got Knots Landing. That was great. I was pretty happy there.

KAISER: Of theater, movies, and TV, which would you rather do?

BALDWIN: I would rather not do TV, but if I had to it would be okay.

KAISER: You’ve outgrown TV?

BALDWIN: No, it’s not a question of “outgrowing.” Early TV was only so many hours out of the day. As we came up with more and more ideas for TV that were really good, TV filled up more hours of the day. It was like a balloon that expanded. The problem now is that the balloon is not contracting in accordance with how bankrupt it is creatively. In other words, CBS or NBC or ABC is not going to get on the air and say, [in an announcer voice] “Ladies and gentlemen, we couldn’t come up with anything for Thursday nights at 10 o’clock this season, so we’re going to show you reruns, something we know you love.” Or “We’re going to remain dark.” Not only do they not do that, they come on with some awful piece of shit and say, [in “hyping it” voice] “NEW HIT SERIES! It’s SANDY DUNCAN and BOB NEWHART in BAXTER’S PLACE! Bob Newhart is a lovable bake-shop keeper in Maine. With his second wife, Sally Duncan.” That’s what bothers me about TV. I loved doing Knots; I thought we had the greatest cast on television—Julie Harris, Bill Devane, and people like that doing TV. It’s the closest thing to a real job you’re going to have as an actor.

KAISER: Do you like all the movies you’ve been in?

BALDWIN: To varying degrees, yeah.

KAISER: There was only one I really didn’t like—not because of you—Talk Radio.

BALDWIN: You didn’t!

KAISER: No. Nothing in it worked. The premise didn’t work, the characters didn’t work, and I thought the attitude of the film was almost the same as the attitude of the main character, which was just contemptuous of everybody in the movie.

BALDWIN: I found the movie irritating. But knowing Oliver Stone, that’s probably exactly what he had in mind.

KAISER: Is he fun to work with on the set?

BALDWIN: “Fun” is not the word. Stone is impenetrable. I don’t even bother to try to figure him out. And that’s not a judgment of him. Eric Bogosian was the lead in the movie, and the special relationship that the lead had with the director is reserved for the lead only. One of the reasons Red October was such a rewarding experience was that I was the lead in the movie. I’ve worked with Jonathan Demme. I worked with John Hughes. He’s bright. He’ll let you do anything.

KAISER: Which movie did you do with Hughes?

BALDWIN: She’s Having a Baby, with Kevin Bacon. But John had that relationship with Kevin. Mike Nichols had that relationship with Melanie Griffith in Working Girl. Demme had that relationship with Michelle Pfeiffer in Married to the Mob.

KAISER: But Red October is the first time you’ve had that yourself. Finally.

BALDWIN: Yeah. You get them. You get all of them. Or most of them. And this was not even a performance-oriented movie, so I can imagine how much better it could be. I mean, John McTiernan, the director, is not Ingmar Bergman. He does action-adventure movies.

KAISER: Compare Nichols with Demme.

BALDWIN: That’s not fair. There’s no comparison. Nichols on the set is very quiet. He’s very concentrated. He doesn’t have anything to prove. He’s very comfortable with who he is. He sits there: “Hello. I’m Mike Nichols.” And you start to wet your pants when you first work with him, you know? I found in the beginning that he’d be talking and I wasn’t really listening to what he was saying. I was just standing there and staring at him. Then you get over all that. Nichols directing—this is limited by the couple of weeks that I’ve shot with him—is somebody who wants you to come up with the idea. He’s used to actors working and creating and coming up with ideas. And he’s worked with such great actors. So when you do a scene he’ll say, “Well, what’s your idea?” If you don’t have an answer, he is going to be very down on you.

KAISER: Did you like that approach?

BALDWIN: Oh yeah! I like being free to make my suggestions. Harrison Ford and Sigourney Weaver and all these heavyweight people—we rehearsed, sitting at a table for two weeks. Nichols is somebody who’ll make you say something. And in the end he’s got plenty of ideas of his own, which he’ll tell you after you speak up.

KAISER: Is he charming with actors, or is he tough?

BALDWIN: Oh, he’s very charming. But then he’s tough. I had to do this nude scene with Melanie, which they cut from the movie. It’s a scene where I buy Melanie underwear, and she says, “Can’t you ever buy something I can wear outside the house?”

KAISER: That’s in the movie, isn’t it, that line?

BALDWIN: That’s in the movie, but then she gets into the bed and I take her underwear off and we start to get into it. I think Melanie was just tired of being naked or half-clothed in the movie. She just looked at Mike with those eyes like, You mean I have to get undressed again? And Mike just looked at her like, Well let’s go! These leaves aren’t going to rake themselves off the lawn, are they? Get to work! You’re a professional actor, aren’t you? I am the director, aren’t I? Well take your goddamn clothes off! He doesn’t really tolerate a lot of bullshit.

KAISER: And Demme?

BALDWIN: One of the most important things about Demme for me is that he does that form of satire, and he does it very lovingly. He’s not vicious. He really is a genius at sending up something without getting nasty. You’d have an idea, and Demme would sit there and nod his head, and his eyes would start to widen, and he’d say [he turns into Demme] “Y-e-e-s? Uh h-u-uh? That’s a good idea. Not for this movie. But that is a good idea.” And then he’d say, “Do it this way.” He helped you. I’ve worked with directors, mostly in TV, who have this “rent an actor” mentality: [turns into a TV director] “You look like the guy. You sound like the guy. Judy: put clothes on. Fred: give him the lines! Don’t you come up with any ideas. We’ll tell you exactly what to do.” I don’t ever want to work like that again.

KAISER: But Demme’s not like that.

BALDWIN: No, no, no. Demme is somebody who wants to hear your ideas. Like Nichols. But Nichols demands to hear them. Both of them validate whatever it is you have to say. But I’ve worked with directors who sit there and wince and say, “Ugghh! That’s stupid! Oh, please! Oh, why did you want to do that?” It’s all one-upmanship.

KAISER: What we call “who’s-boss editing” in this business.

BALDWIN: Who’s boss? Who’s smarter, who’s more creative? Goddamn it! It’s a pain in the ass!

KAISER: Can I have a fortune cookie? What’s your fortune?

BALDWIN: “Absence makes the heart grow fonder.” You know, I’ve never heard that before. What’s yours?

KAISER: “We cannot do all things.”

BALDWIN: Well, in your case I’d say that’s especially true.

KAISER: Obviously true enough. How did you like doing Serious Money?

BALDWIN: Loved it! Hated doing it until the bitter end and realized what a fabulous experience it was and how challenging it was. I was overwhelmed by it. Hardest thing I’ve ever done. I read the script and said there was no way on earth, even with a gun to my head, that I wouldn’t do this show. I might not have done it all that well early on, but I think toward the end I got a lot better. I started to do it, rather than it doing me. My hat goes off to Joe Papp for producing it. He really tried to bring some depth to Broadway. We should have done it in a small theater. In New York, businesspeople now have all the money. They’re the ones who buy the tickets to the theater. So the people we were satirizing and bashing in the show were the people in the audience, and they have no sense of humor about themselves. The wealthy don’t have any sense of humor. It’s not like the English, where the theater is perhaps the one place where they have a sense of humor about themselves. The second thing, as someone once pointed out to me, is that an evening in the theater in New York is typically a woman’s evening. Look at the shows that are really successful on Broadway. They’re musicals. They’re things that a woman will pick out the tickets for, or a man will buy the tickets with a woman in mind. It’s a date. It’s boyfriend-girlfriend, husband-wife. That’s what the theater in New York has become. Every now and then they’ll serve up one dish of Fences or Joe Turner’s Come and Gone or something like that. People didn’t want something like Serious Money. Plus the show was done at such a fast pace. We’d try to lay it out a little more for the audience, and the director would say, [in a very English voice] “Oh no. You cahn’t do that at all. You must appeal to the highest denominator in the audience. I refuse to do the show and calibrate it to some American bourgeois mentality. If they don’t get it, fuck ’em!” [in his own voice] And we closed in five weeks.

KAISER: Did you have to do an accent like that in the show?

BALDWIN: [back to the accent] Yes, I did! I talked like this the entire show. I can talk like this for months at a time! At home. On the phone. [back to his own voice] No, I did. It really took over. I did that in Loot too. But I loved Serious Money. It was a great opportunity. Do I sound awfully cheery? “Oh, I loved Knots Landing. I loved The Doctors. Oh, I loved Serious Money.” I loved it all!

KAISER: Except for that one movie you told me you didn’t love, which you’re not talking about.

BALDWIN: It wasn’t the best work we could do… I saw a PBS program on the making of Death of a Salesman with Dustin Hoffman. They’re watching a sequence in the dailies, if I remember correctly, and Dustin Hoffman says, [in a Dustin Hoffman voice] “No, no, no! We got to do that again. That’s not our best work. That’s not our best work!” And I thought to myself, When you’re Dustin Hoffman and you see something you don’t like in the dailies, you can say, “Let’s do it again.” Usually when you do movies, you don’t get that opportunity. So rehearsal is critical. If I’m doing a TV show or a movie of the week, and the director’s in his trailer talking to his girlfriend on the phone or buying real estate up in Montecito… then I’m gonna walk. That was the thing I loved about McTiernan. He never even went to the bathroom! We wondered if the guy was human.

KAISER: Who else is in Red October?

BALDWIN: Sean Connery and I are the two leads. Scott Glenn, James Earl Jones, Sam Neill, Courtney Vance, Tim Curry.

KAISER: Not bad. Did you know Sean Connery before this movie?

BALDWIN: Absolutely not.

KAISER: You weren’t alive when Dr. No was made. What year were you born?

BALDWIN: ’58.

KAISER: Oh, ’58, I beg your pardon. You were an old guy. You were about four.

BALDWIN: Sean was wonderful to work with in every way. When you’re with somebody who has made 40 or 50 films, he usually knows more than the combined total of everybody else on the set about making movies.

KAISER: Is Sean a nice guy as well?

BALDWIN: Yeah. Very. Very polite, for the few moments we had that we could sit down and talk—because he was shooting for only about four weeks. You get Sean for X number of weeks, and you’ve got to roll the cameras and get al his scenes. So when Sean was shooting, he wanted to [snapping fingers] keep moving. When we did Working Girl, Harrison Ford was the same way: “You’ve got me for four or five weeks,” and then he’s out the door.

KAISER: You finished Red October two weeks ago?

BALDWIN: About 10 days ago.

KAISER: And what have you done since then?

BALDWIN: I published a novel. I accompanied Jacques Cousteau to study the effects of…

KAISER: You’ve been sleeping a lot.

BALDWIN: I’ve been sleeping, working out, seeing friends. Eating, relaxing, reading Henry Miller. I’m going to play Miller for the next four or five months in Phillip Kauffman’s new film—he did The Unbearable Lightness of Being. It’s called Henry and June. It’s based on a book by Anaïs Nin about her relationship with Miller and his wife, June. I play Henry. I wanted to play June, but they wouldn’t have it.

KAISER: Who else is in the cast?

BALDWIN: Kevin Spacey. Richard E. Grant, who was in Withnail & I and How to Get Ahead in Advertising.

KAISER: Have you read everything Miller has written?

BALDWIN: No. I’m in the process of doing that now. But all these nosy reporters keep interrupting me.

KAISER: What have you read so far?

BALDWIN: I’m in the middle of Nexus and I’m in the middle of Tropic of Cancer. At first I had to get through all the bullshit about Miller—that he was a dirty-book writer, and these still photos of Miller playing Ping-Pong on the Pacific Palisades with a topless Playboy Bunny type, and all that absurdity.

KAISER: Do you have a view now of who he really was?

BALDWIN: I’m in the process of developing that view. I have this idea in my head about people who lived before nuclear weapons were on the horizon. They guy ate when he was hungry. He slept when he was tired. He got up when he wanted to. When he wanted to paint, he painted. When he wanted to fuck, he fucked. When he wanted to be with friends, he’d be with friends. Miller was very present wherever he was. That’s one of the great crimes of contemporary life, I think, especially metropolitan life—so many people never are where they are. I’m trying to live that life now. And I know when I go to France it’ll be one of the great benefits of being there. I’m just going to give myself completely to the experience and always be in the moment that I’m in. Like here with you. I knew I couldn’t be in this moment with you unless we went and got this good, because I was dying. I wanted to come here and do this with you, and not be thinking about how much I hate it, how much I hate reporters and interviews. Which I do.

KAISER: It doesn’t show at all. You must be a good actor.

BALDWIN: I’m a great actor—when it comes to that.

KAISER: You’re not really having such a terrible time. Is this misery?

BALDWIN: I could sit here and say lots of things that are interesting, but that wouldn’t be a really healthy me. To say negative things, for instance. I want to just go and do Henry and June. This movie is like a huge mountain that’s looming in front of me. It’ll be very hard to portray a historical figure. The only other time I’ve ever done that was when I played Jimmy Swaggart in Great Balls of Fire, and I portrayed him when he was young, before all of what he’s most commonly known for occurred. Caryn James, who writes for The New York Times, said that I was “suitably slimy” as Jimmy Swaggart. I was really dismayed by that, because she didn’t get what I was trying to do. I wasn’t trying to be slimy at all. I was trying to be sincerely reverent, like he was. Because back then he was for real. You can’t foreshadow what someone’s going to become. Dennis [Quaid] and I wanted to put a scene in when Jerry Lee goes on the plane to London; we wanted Jimmy to grab Jerry Lee and say, “Is there room on that plane for me?” Because Jimmy Swaggart wanted to be a musician, and he was jealous of Jerry Lee.

KAISER: Was Dennis fun to work with?

BALDWIN: Dennis was great to work with. I was knocked out by Dennis. So many actors in films don’t give a shit. They don’t put anything out there at all. And Dennis gave and gave and gave. I mean, he has the sofa ripped out of his motor home and put in an electric piano. And every day between takes, Dennis was rehearsing the piano. He knocked me out. I’d never met him, and I didn’t know what to expect. He was so hardworking. And when this movie was done, people said to me, “Hey Batman.” “Hey! Lethal Weapon 2,” and “Indiana Jones,” and all these other movies. And I said, “Great Balls of Fire is going to be the best movie of the summer.” When it came out and flopped, I was totally shocked. Then I saw it and I could see that there was something wrong with it, but just on the strength of Dennis’ performance alone, I thought the movie was going to be great. People say Dennis was over the top, but that’s what Jerry Lee Lewis was. He was a total madman. He was insane.

KAISER: Jerry Lee Lewis was on the set too, wasn’t he?

BALDWIN: Yeah. He was around. I think Jerry Lee is sad. As a musician he was far more talented than Elvis Presley. Everybody down in Memphis knows that. Elvis became a movie star because he was beautiful. Not that Elvis wasn’t talented, but Jerry Lee Lewis was incomprehensibly talented as a musician. But all that scandal marred him. There was that train of early pop stardom that took off, and fortunes and careers were made. Jerry Lee should have been on that train, but it took off without him. And I think he’s very, very unhappy and bitter about that to this day. Jerry Lee doesn’t have one percent of what he’s entitled to financially. I think that pisses him off. He’s still a very dangerous-looking guy, a scary-looking guy. I mean, in his eyes. He looks like he’d kill you. They call him “The Killer.”

KAISER: What kind of politics did you grow up with in your own family?

BALDWIN: Total lefty, Kennedy Democrat.

KAISER: Do you remember when John Kennedy was killed?

BALDWIN: I remember exactly where I was. I was sitting in my friend’s backyard on Long Island, in a little wading pool filled with ice. It was cold. His mother ran out with tears in her eyes, screaming that Kennedy has been filled, and she grabbed us both by the arms and scooped us up and brought us into the house. I went to Bobby Kennedy’s funeral mass at St. Patrick’s when I was ten.

KAISER: You got in?

BALDWIN: My father, my brother, and I stood on line. The line went from the door on 51st Street to Park Avenue, and then down Park Avenue all the way past the Pan Am building, and then wrapped around. I remember moving along the line slowly with the Pan Am building and the Helmsley building in the background. We inched toward the entrance and went in. There was all this scaffolding above for the network TV cameras, and this guy from WMCA radio interviewed me when I walked in. He stuck a mike in my face and asked me if I was there to pray for Robert Kennedy, and I said yes. He said, “What are you going to say?” and I said, “I’m going to say an ‘Our Father.'” And he said, “Is that it?” I said, “What do you mean?” He said, “Well, how does it go?”

KAISER: And ever since then you’ve loved every reported that you’ve ever met.

BALDWIN: I guess that was it. Here at this very tender moment, Robert Kennedy’s funeral—

KAISER: With this asshole.

BALDWIN: This gaping asshole came up to me with this microphone and fucked up my whole afternoon.

KAISER: Are there any politician whom you are impressed with today?

BALDWIN: I guess not. We’re in an age of very low expectations. People don’t care about anything, really.

KAISER: You told me what they cared about earlier in the elevator.

BALDWIN: Their nose, their dick, their wallet. Who’s on Live at Five this afternoon. I’m not impressed with anybody now. It seems that just when you thought it couldn’t get any worse it did. I’d like to think that good people would devote themselves to what Kennedy called “public service.” Now everybody who has any talent wants to turn it into something financially rewarding. You know, make some money while you can. And maybe eventually you’ll go into politics.

KAISER: You don’t have any problems with that attitude?

BALDWIN: I don’t have a problem with prosperity, if you have the opportunity to make a lot of money in an ethical way, and to apply yourself, work hard, and get somewhere in your chosen profession. I don’t find anything wrong with that, but I think you then have an obligation to give back. I don’t think I’m going to do this for the rest of my life—become a movie star, make millions of dollars, and just do that, travel and go to Cannes, have my picture taken and all that bullshit. I don’t intend to do that.

KAISER: What do you intend to do?

BALDWIN: I don’t know. But I’d like to get into something where I can give back what I’ve gotten.

KAISER: I thought you wanted to run for office.

BALDWIN: That’s a possibility. But you don’t necessarily have to be a candidate. You can be in the background. As time goes on and as more people like Alfonse D’Amato become senators, I start thinking, Well, this is it. If Alfonse D’Amato can become senator, I’m going to be the governor of the new colony on Mars. You know what I mean?

KAISER: But why not run, eventually?

BALDWIN: Well, I’m not ruling it out. Or I could become involved in an issue—there’s a group called the Environmental Defense Fund, which Senator Tim Wirth and his wife run. I met them at the convention. I could become a big fund-raiser for the EDF in my space time. I would like to become involved in fund-raising for the arts. I mean, especially now, with this Jesse Helms thing, and congressmen saying they don’t want to give money, because Mapplethorpe’s work glorifies homoerotica. [laughs] I want to open a clothing store called Homoerotica right on 57th and Fifth. I’m gonna have TV ads and everything. And I’ll have Mapplethorpe’s work all over the walls. I want to just shove it down people’s throats. [in a snooty English salesperson’s voice] “Good afternoon. Will this be cash? Or your Homoerotica charge card?” Anyway, this whole Jesse Helms thing—he’s a very dangerous guy, a very sick guy. And he is a sign of the times. He should just sit down and be quiet and drool on his tie. You know, in the Reagan years they cut the administration of the National Endowment for the Arts and the Humanities drastically. And now they want to tell people how they can and can’t spend it. So that’s another field I want to get into.

THIS INTERVIEW ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN THE OCTOBER 1989 ISSUE OF INTERVIEW.

For more New Again click here.