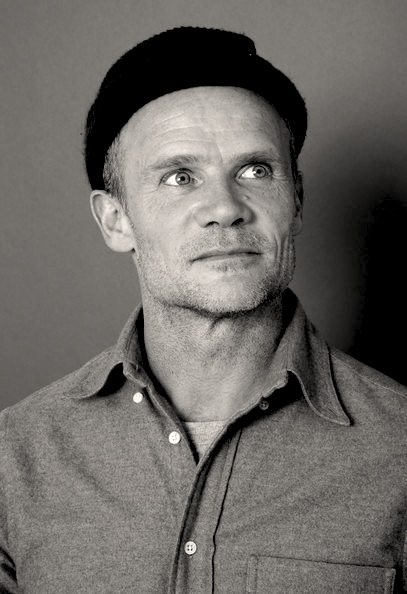

Flea by Ninja

ABOVE: FLEA AT THE SUNDANCE FILM FESTIVAL, JANUARY 2014

Low Down, Jeff Preiss’ feature-length debut, is not an easy film to watch. Set in L.A. at its seediest in the 1970s, Low Down is based on Amy Jo Albany’s memoir about growing up with her father, the jazz pianist Joe Albany. As a young teenager, Amy is surrounded by heroin addicts: her next door neighbor is an addict and prostitute, the kind man downstairs an addict and porn film extra, and her father and his friends overlooked jazzers and junkies. Her mother, who periodically appears at Amy and her father’s doorstep, is also an addict, and a particularly cruel drunk. But Amy adores her father, and he adores her too. She wants only to see him succeed and instead watches him repeatedly destroy himself.

The film, which premiered at Sundance in January and opens tomorrow, stars Elle Fanning and John Hawkes as Amy and Joe, with Glenn Close as Amy’s grandmother, Lena Headey as her mother, and the Red Hot Chili Pepper‘s Flea as Joe’s close friend, a trumpet player named Hobbs. Flea also produced the film alongside his bandmate Anthony Kiedis—a first for the bassist.

Throughout the last 30-odd years, Flea has appeared in over 15 films including Back to the Future Part I and II (1985, 1989) Gus Van Sant‘s My Own Private Idaho (1991) and Psycho (1998), and Fear in Loathing in Las Vegas (1998). His role in Low Down, however, is his most significant to date, his transition from musician-who-acts to actor. Here, Flea talks to his good friend Ninja from the South African hip-hop trio Die Antwoord about his experiences filming Low Down.

EMMA BROWN: Hi Flea. You’re on with Ninja.

FLEA: Man, I’ve been running around doing all this film stuff, it’s crazy. Now I’m sitting up in a hotel room with Sandha [Khim] in New York. How are you?

NINJA: Nice, I’m in Africa. I’m in the African world.

FLEA: How is it?

NINJA: It’s wonderful.

FLEA: Great, man. How’s Tokkie?

NINJA: He’s cool. He’s super happy to be back in the zone. I can’t take him too far from here. He digs it here. He needs his regular dose of hood.

FLEA: [laughs] I wish I could be there with you guys.

NINJA: When’s the [Low Down] premiere? Tonight?

FLEA: The premiere’s tonight in New York. I know you haven’t seen it yet; it’s a pretty sad movie. It’s a super personal movie about this girl’s life that I know—my friend. It’s about this really dark, sad part of her life. Her dad is a jazz musician, but the story takes place when she’s a little girl and he’s totally strung out on heroin. It’s hard stuff to watch. I feel like for her, it’s hard, ’cause everyone sees it and then they look at her like they feel bad for her or something. She’s really cool, but it’s a hard position for her to be in even though she got her story made into a movie. The book [Albany’s memoir] has a lot of humor in it, and the movie doesn’t really get into that part. It’s more of this dark meditation on this other part.

NINJA: How did she hit you up, the girl that wrote it?

FLEA: It was weird because her life is so close to mine. It’s insane how close it is. We’re the same age, we both grew up in Hollywood—I was blocks away from her—and I had a jazz musician parent who was a drug addict and alcoholic. They were part of the same jazz scene in L.A. and both of us kids were the same age. We both got left home and were running around the street and both became punk rock kids. Once I met her in a grocery store and I hit on her. She was with her grandma.

NINJA: [laughs] That’s so funny.

FLEA: I know. So, should we do this interview?

NINJA: I thought this was the interview?

FLEA: Yeah, this is the interview. We’re doing good. [laughs]

NINJA: You’re in all these other films popping up in scenes here and there, like My Own Private Idaho, The Big Lebowski, and Back to the Future. When I saw rappers in the ’90s cameo in films—all of those ’90s rappers—it seemed like whenever you chucked a rapper in a film, they could just act. It seemed like all rappers could act. But they were all really similar to themselves. Whenever I’ve checked you in films, you have a ‘’90s rapper style of acting—you’re just you, doing your thing. Was this a similar kind of thing? Or did you have to trip back and zone out?

FLEA: It was really different. I like the idea of acting. Of all these things I’ve done, sometimes I think I’ve done well and sometimes I think I didn’t do well, but they are more cameos and I come in and be crazy. But in this one, it was the first time I felt like I really had to act; I had to be someone I wasn’t. I play a really pathetic junkie and you know me: “Almond milk, please, and brown rice and organic blueberries, please.” When I was a kid, I did a bunch of heroin so I knew what it was to be on heroin. But I didn’t know what it was like to be an unsuccessful jazz musician who was strung out on heroin, who was kind of bitter and fucked up, but still had hope because of the beauty of the music. It took a lot of preparation, a lot of work, and I had an acting guy who helped me and taught me how to prepare.

NINJA: Was it fully scripted?

FLEA: It was all scripted, but a lot of it ended up being improvisation on the set, and a lot of the improvisation got used. But what was cool was—when I play music, and it’s probably the same for you when you’re rapping, when it’s at it’s best, when it’s really fucking, when it’s on, it’s like you’re in an ecstatic trance. You’re not thinking anything. It’s this thing fucking flowing through you and you kind of disappear into it. With acting, I always feel conscious of what I’m doing. This was the first time where I had that feeling like when I play music.

NINJA: The magic happened.

FLEA: The magic happened, and it had never happened to me before. I think it happened because I was going through this really hard time. I had broken up with my girlfriend. I wanted to get her back; she wouldn’t come back. I was really miserable. I wasn’t sleeping. I was bugging out and I wasn’t eating. I think my own personal unhappiness at the time really served the part for the movie.

NINJA: When you were filming?

FLEA: Yeah.

NINJA: Oh, shit, really? Jeez.

FLEA: Yeah, but I think it really helped. At the time I felt a lot of sadness—just questioning my own existence—so I was able to channel the pain into the movie. Before I could always do that with music, but I hadn’t really been able to do that with acting as much. It was a real lesson in how to let go and let this shit inside you come out when you act, as opposed to thinking about how you’re going to do it and putting it together.

NINJA: How long did you shoot for?

FLEA: Not that long. This is a real low budget movie—they shot the whole thing in less than a month. I shot, like, a week.

NINJA: What does it mean for you to produce the film?

FLEA: I just gave money, basically, and I helped with some stuff. I helped them get music together; I helped with casting. I recommended some people that worked out. I met with them to act in it and I got really into it because I believed in it so much. Not so much it being close to my own personal story—being so similar to Amy—but also the jazz music I grew up with. I grew up with all these old jazz guys in the ’70s in L.A., and they grew up idolizing Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus, Lester Young—all of these incredible musicians. They dedicated their lives to learning this fucking sophisticated, deep, spiritual craft, and come the ’70s, nobody gave a fuck about them. They couldn’t get a job. They were these incredible artists, but they were out of time. Because of that, a lot of them had drug problems. A lot of them were bitter and angry about it. Some of them were really cool and figured out how to make it work, but it was really hard for a lot of them. That’s what it was like for my stepdad. I grew up around these guys and they were beautiful guys, but they just couldn’t catch a fucking break. They didn’t know how to translate it into something great. Miles Davis was smart enough to start making electric records, but they didn’t know how to do it.

NINJA: When is the movie set?

FLEA: In the early ’70s in Hollywood. It was really important to me to shed a light on those guys and that time—there’s a funny juxtaposition that didn’t really fit. It’s sad, but kind of beautiful and really interesting too. It meant a lot to me to have a movie about those guys.

NINJA: It’s super dope when you connect with something personally.

FLEA: Yeah, you’re so good at that in the way you’re making hip-hop—you feel this whole culture coming from Africa that we don’t know anything about in America. I know a little bit about it from hanging out with you over there, but for all of these people watching “Baby’s on Fire” on their YouTube, they feel the feeling of a different culture. And that’s dope.

NINJA: Shit just goes down all the fucking time. This morning, I was having breakfast and I hear screaming. I step out onto the street and some dude’s smashing some other dude’s head in with a crowbar. The guy had snuck into his house—he woke up with this dude in his house. The maid had screamed, and the guy that broke into the house had stabbed the maid on his way out the window. He caught him and was smacking the shit out of him. The cops took about 45 minutes to not come, as usual, so the dude took the guy by the shirt and walked him to the police station. And then everyone goes back to having breakfast. “That was exciting.” I was skimming the questions that Interview wanted to ask, and I think it’s kind of funny how you and me met.

FLEA: Oh yeah. You put your hand on my face. [laughs]

NINJA: When we were in Belgium. I think it was in Belgium.

FLEA: Somewhere in Europe. We were at a festival together.

NINJA: Chili Peppers and Die Antwoord were playing at the same festival. Yo-Landi [Visser, Ninja’s Die Antwoord bandmate] is super, not antisocial, but she doesn’t really like to mingle and like being around people. It was the soccer World Cup, and all the artists at this festival were backstage watching the World Cup final. Yo-Landi is sitting on this bench and out of the corner of her eye she sees this weird guy come and sit next to her with no top on playing the fucking shit out of a bass that’s not plugged into anything. She tapped me on the shoulder and was like, “Ninja, can you tell this dude to fuck off.” I was like, “Whoa!” Then Flea was like, “Hi” and I was like, “Whoa, Jesus Christ. I love you.” And then you were like, “We’re playing in Africa soon.” I said, “We should open for you,” and you said, “That’s a great idea. Speak to my manager.” Then I told you, “Don’t forget!”

FLEA: I remember that part.

NINJA: Then you said, “I’m going to go now.”

FLEA: That’s when you started getting fucking weird.

NINJA: I do this thing with my daughter—I put my hand on her face and shake her head, but really affectionately. But I didn’t think and I did that to Flea. Later I was hanging out with [producer] Money Mark, and Money Mark told me, “Flea’s all freaked out by you because you put your hand on his face and shook his head.”

FLEA: [laughs]

NINJA: And I was like, “Why?” But my sound engineer was sitting there and said, “Ninja you’re taking it too far.”

FLEA: [laughs]

NINJA: “You don’t touch his face. You don’t do this to people.” What did you think I was doing?

FLEA: [To Interview] Emma, are you there?

BROWN: Yes, I’m here.

FLEA: So I show up at this festival—and a lot of times I just show up, do the gig, and I get the fuck out. I’m not a big socializer. I don’t hang around much. But I look to see who’s playing and it’s always a bunch of rock bands that make me want to go to sleep—pretty much every contemporary rock band—but I see Die Antwoord is playing and I’m happy about it. I’m really excited. I like soccer; I see they’re playing. I walk out. I see Yo-Landi sitting there and I want to say hi. I see she’s being a little bit standoffish, and I’m like, “Oh, she wants to be left alone. I understand.” Then Ninja pops up and we start talking. I’m really happy to meet him. He’s tall, right, and he has big hands—

NINJA: I’m not that tall.

FLEA: You are compared to me. He puts his whole hand on my face—like a thing in a horror movie where some guy has a power and puts his hand on your face and melts your face or sucks the life out of your soul. It was this crazy crab hand.

NINJA: Fuck off, dude. [laughs]

FLEA: He covered my entire face with his hand and shook my head around. And I was just like, “What the fuck?” I didn’t know if it was a sign of affection or some weird-ass African ninja curse.

NINJA: I don’t think I’ve ever done that to anyone [else]—only to you and my daughter. I was like, “I love this guy so much. He’s so cute.”

FLEA: Then afterwards we get to play with you guys and you’re just super gentle and sweet and nice.

NINJA: Yeah, I’m the nicest person in the world. Possibly. We were trying to get a house in L.A. because we’ve been working there for a while now. Every time we’d find a house and it was all going cool and we’d put in an application, they’d Google us and go, “No fucking way.” We got turned down five or six times. You know how I finally got a place? I wore white to look like I did yoga or something. To look more holy.

FLEA: I know your white suit.

NINJA: People were really feeling it. That really worked.

FLEA: Is it the same [in Africa]? Because you’ve got tattoos on your face and in America, tattoos on your face is a jail thing.

NINJA: I’ve only been to jail once, and I didn’t get my tattoos there.

FLEA: I only went there once, too. I didn’t like it.

NINJA: Yeah it sucks. I’m never going again.

FLEA: So when you wear white they think you’re reformed and have become some sort of spiritual guru guy.

NINJA: Yeah, I looked super guru-ed up and they were like, “They’re not going to play.”

FLEA: [laughs]

NINJA: I looked super peaceful. Anyways, it’s cool now. I’ve got a place now. It’s awesome. Have you made your tooth gold yet?

FLEA: No, but I went to the dentist and I talked to him about it.

NINJA: Is it happening?

FLEA: I asked him, “What’s it like when you have gold in your mouth? Is the metal healthy for you?”

NINJA: It’s gold, dude. It’s the best. People have traces of gold in their blood. Just get it. People will know that you’re rich if you have gold in your teeth.

FLEA: [laughs] People already know, I drive a Tesla.

NINJA: Oh and have you made your Tesla matte black yet?

FLEA: It’s going to have to get some bodywork done because I drove it into the trash cans…

NINJA: Dude, you’re slacking. You must get this shit hooked up. Next time I see you, you have to have a gold tooth and a matte black Tesla.

FLEA: [laughs] I’m on it.

NINJA: Check your texts from me.

FLEA: Alright, hold on. [laughs]

NINJA: And that’s what is what like!

FLEA: What is that picture from? A weird movie?

NINJA: I don’t know. That’s me saying hello to you.

FLEA: That’s what it was like. The anguish of the face with that hand on it: “What is happening to me?”

NINJA: Send that to Emma. It’s called “when Ninja met Flea.” I’m sorry that I did that, dude. I won’t do it again.

FLEA: I’m glad you did it. We wouldn’t be able to talk about it [otherwise].

NINJA: I think it was the best intro.

FLEA: I thought of a really good rap lyric for you yesterday but I can’t remember it.

NINJA: Aw Jesus, stop smoking weed.

FLEA: Remember the one about Dolly Parton?

NINJA: Yeah that was brilliant. X-rated though.

FLEA: [laughs] Yeah.

NINJA: I don’t know what rhymes with Dolly Parton. You don’t have to rhyme anything with that, it’s so good.

FLEA: [laughs] Alright. Well, I miss and love you dude. I’ll see you soon.

NINJA: Yeah, catch you on the flip.

LOW DOWN COMES OUT IN LIMITED RELEASE TOMORROW, OCTOBER 24.