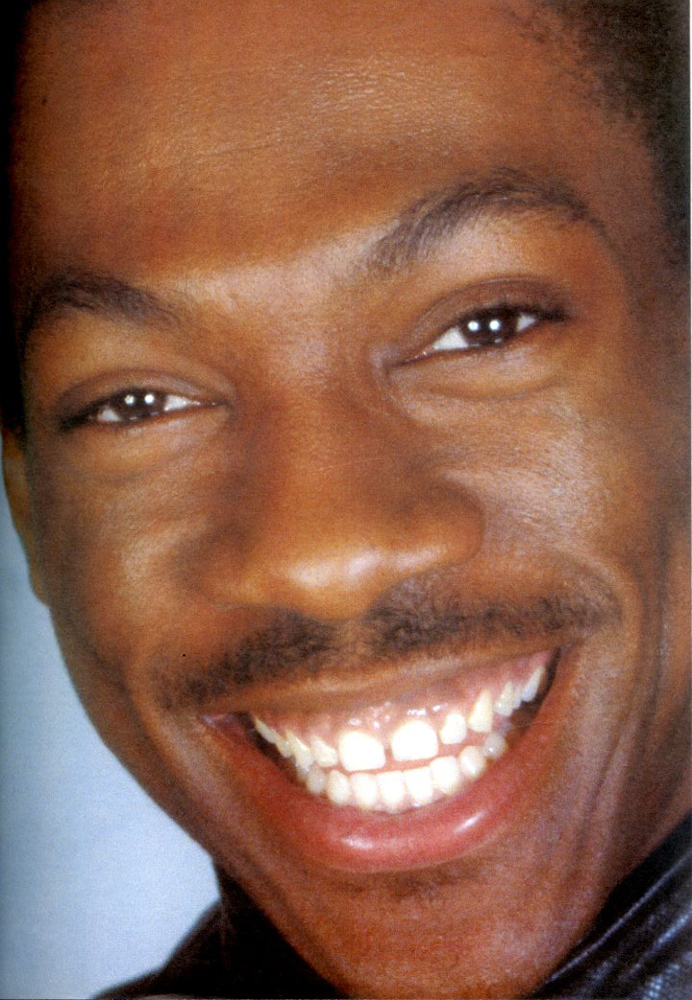

Eddie Murphy

Entering Eddie Murphy’s compound, a rented home tucked neatly away in Beverly Hills, is a little like walking into a hugely overpriced college dorm. Moving inside past the carport, which harbors a shiny new Porsche and a stately Rolls, you find Eddie’s boys lounging around, while Murphy himself is upstairs recuperating from a night that ended at 7 a.m. The huge, serviceable house’s glass-encased bookshelves are filled with videocassettes; the preferred reading seems to be the “Life” section of USA Today, which, conveniently, also contains the TV listings. Sitting in the den, gazing distractedly at televised women’s gymnastics, are Murphy’s brother, Charlie—who, although slimmer and older, bears a strong resemblance to Eddie—and Richie Tienken, one of Eddie’s managers. They talk amiably about preparing the country for a Murphy land assault. Eddie’s planning a tour, which should dovetail into the opening of Eddie Murphy Raw in December. Raw, Murphy’s first theatrical concert film, was directed by fellow comedian Robert (Hollywood Shuffle) Townsend. This interview was conducted in February, during the litigation with former Murphy manager King Broder, and before Tienken—who has a small role in Beverly Hills Cop II—was dismissed. The Broder suit was reportedly settled for about $700,000. Murphy has since been involved in other troubles, which include a paternity suit filed in April and an Atlantic City investment scam into which he put $240,000. The good news is that Murphy has announced plans with Hanna-Barbera to begin an animated Eddie Murphy series. Apparently there is some justice, after all.

When Murphy enters, a subtle change takes place in the room’s atmosphere. The fellas, catching a whiff of house royalty, assume a modestly servile stance: nothing that would be immediately noticeable—there are no clicking heels or salutes—but it’s evident they aren’t just cooling out and buzzing past cable stations at a friend’s joint. Eddie offers a friendly greeting and moves the interview session into the cavernous living room.

My initial impression is that Murphy is much bigger than expected; he must be about 5’10” and 160 pounds. He has the deliberate grace of an athlete, but it’s more like the wary cool of a first baseman than the intense spring of a boxer. He dresses like an athlete too, wearing red workout shorts, black Adidas aerobics shoes and a black sweatshirt with a raised “Adidas” on the front—an emblem of casual urban cool. He also has a finer-boned handsomeness than I expected. Along those lines he jokes about what was probably the most important contribution supplied by Beverly Hills Cop II director Tony Scott: “I wanted him to make me look as good as Tom Cruise in the volleyball game in Top Gun.”

“Well, let’s do it,” Murphy says, sitting down before the tape recorder. It’s not so much that he wants to slide headfirst into the interview, but more that he wants to get the whole thing over with as soon as possible. His soft-spoken calm belies an attention span that leaves no time for dawdling. He has a sharp, fast-moving and easily bored mind. His concern is for the now, the immediate. Questions about specific past incidents draw a bored “yeah,” and his eyes return to half-mast, as if commemorating the death of his interest in the conversation. Inquiries about his music engage him; his eyes gleam as he leans forward and explains the type of bottom-heavy funk he’s currently exploring. He invites me to a makeshift studio in his bedroom, where he blasts out some of his pleasing but faceless pop/soul demos. Murphy, like most comedians, is not hyped and “on” when not playing to an audience, but he’s not depressive and withdrawn either.

There has been much talk of what has made the 26-year-old Murphy a star, and the most common explanation has been his fearlessness before the camera. But he’s also camera-literate in the way that kids speak “computerese”; he naturally and instantly assimilates information that sharpens him as an entertainer. This may also account for his powers of mimicry; he can imitate virtually anyone after only a few moments of observation. Murphy’s incredible facility has probably made it much less taxing for him to develop his immense talents. With the exception of Best Defense, the movies he’s starred in—48 Hrs, Trading Places, Beverly Hills Cop, The Golden Child and Beverly Hills Cop II —have succeeded by the sheer force of his persona.

ELVIS MITCHELL: Did you ever see the capsule review of The Golden Child in the L.A. Weekly, where, in effect, Michael Ventura called you “Paramount’s house nigger”?

EDDIE MURPHY: He called me what?!

MITCHELL: He wrote, “Hasn’t he degenerated merely into Hollywood’s favorite nigger, a pickaninny doll who laughs when we want him to laugh, at what we want him to laugh at?…”

MURPHY: This must’ve been some white guy, right? Thanks a lot, Elvis. You just made me a million dollars. [Yells] Hey, Frooty! Hey, Frooty!

FROOTY: Yo, what’s up?

MURPHY: Have you heard about this L.A. Weekly review of The Golden Child? The guy who wrote it said I was Hollywood’s favorite nigger, a pickaninny doll.

FROOTY: No, man. Let me see if I can get an old copy.

MURPHY: Fuck that. We can sue them. Yeah. We can get them on…that character thing.

MITCHELL: You mean defamation of character?

FROOTY: Defamation of character. That’s what we can get them on.

MITCHELL: I don’t know, Eddie. I don’t think you can sue them for defamation of character. I’m sure you can demand a public apology from them, though.

MURPHY: I’m gonna do something. How could he even fix his mouth to say something like that? Remember when Life had that photo session to celebrate Paramount’s 75th anniversary? Just about everybody came—every big star who worked in a Paramount picture, from Elizabeth Taylor to Robert De Niro. It was a historical thing, right? Then I noticed I was going to be the only black face in the picture. So I decided not to do it. I figured 25 years from now, for their 100th anniversary, when they’ve got a lot more black faces up there, I’ll be glad to take part in a picture.

Shit, how could he even fix his mouth to say something like that? You know, the press has been after me for a long time. That’s why I don’t do interviews. One of the last one’s I did was with Newsweek, when Beverly Hills Cop was about to come out.

MITCHELL: You talked briefly about Best Defense in that interview, making fun of yourself for doing it. How did you end up in that movie, anyway? Didn’t you even turn it down once?

MURPHY: Yeah, I turned down the lead role, but Paramount was determined to get me in the movie. They finally came back with an offer of a million dollars for something like a couple weeks’ work. Now, I want you to tell me a 22-year-old is going to turn down a million dollars for two weeks’ work? But there’s always been a lot of negative stuff written about me. That’s why I don’t pay any attention to the critics. They’ve never liked anything I’ve done.

MITCHELL: I remember Beverly Hills Cop getting a lot of good reviews.

MURPHY: Well, they really came down on Golden Child. But you know who my critics are? The audience. They came out and spent $70 million to see Golden Child. So what do the critics know? It’s the way the audience reacts that matters. I just don’t have any use for critics. They just sit back and tell you that what you do is wrong.

MITCHELL: You’ve never learned anything from what a critic wrote about you?

MURPHY: How can they fix their mouths to say some of the stuff they say about me? They don’t know why I do what I do. So why do I need what they say about me? That guy from Time [Richard Corliss] had a good line about me in Golden Child. He said I was trying to be the Indiana Jones of funk. I liked that. But mostly I don’t see that they understand much of what I’m about. Like that guy from L.A. Weekly.

MITCHELL: Any good critic will try to thoughtfully analyze your work. Don’t you ever analyze what you do? When you write your material, isn’t it important for you as a comedian to know what works for you and what doesn’t?

MURPHY: I think I have enough of a sense to know what works for me and what doesn’t, without going into some big thing and analyzing what I do. I’m in a position that allows me to do what I want to do, and I do it.

MITCHELL: What works better for you? Do you think of yourself more as a comic actor or a comedian?

MURPHY: I’m a comedian who got into movies, so I don’t really think of myself as an actor. I started out as a stand-up comedian. And that’s what I’m most comfortable doing. Making movies is time-consuming and it’s boring. You spend most of your time waiting between takes. It’s like a big machine that moves slowly. And you have to work in what you do with what somebody else is doing. It all has to fit together. Now that’s cool something. Like in the Cop movies, Judge [Reinhold] and John [Ashton] and I were comfortable improvising, and it took off somewhere. But that doesn’t always happen. When I’m doing stand-up, it’s just me depending on me. I know how to go out there and make people laugh. I’ve been doing it since I was a teenager. I trust my instincts. I just go out and talk. A lot of the time I let the material come from the top of my head. But I liked doing stand-up more when I was not so well known, before my material was looked at as “what Eddie Murphy said.” When I wasn’t so well known and I did my act, I just got laughs and wasn’t put in this spotlight. It wasn’t like every time I said something about somebody it turned up in the paper the next day: “There’s Eddie Murphy being controversial again.”

MITCHELL: When did it occur to you that you had become “Eddie Murphy” and your statements carried so much weight?

MURPHY: I never think that way. My people say, “Hey, you’ve got to watch out because of who you are.” But as far as I’m concerned, I’ve always been “Eddie Murphy.” When I was in high school, I used to wear a suit, a shirt and tie with a collar pin, carry a briefcase and have my cashmere coat slung over my shoulder. And everybody would say, “There goes Eddie Murphy.”

MITCHELL: What’s interesting about you is that you seem to be this suburban kid who’s made it. But as a teenager, instead of working at a supermarket to pick up pocket money, you did your stand up act every week.

MURPHY: That’s it exactly. I had other kinds of jobs, like every other kid. But on most weekends, I’d go out and play Jersey or Washington, D.C. I started out doing weekends in New Jersey because you had to start somewhere. Then I moved on to the comedy circuit, playing clubs in Cleveland or wherever. Then I got into the Comic Strip [a New York club].

MITCHELL: I’ve heard that you just turned up at the Comic Strip one night, after having been recommended by a friend, and said, “When do I start?”

MURPHY: It didn’t happen like that at all. A friend of mine told me I should start trying to work out at the Comic Strip. I went over and introduced myself, and I got out at the bottom of the rotation and worked my way up. And I went on from there to do Saturday Night Live.

MITCHELL: What are your feelings about SNL now? Would you ever go back and host?

MURPHY: No. As far as I’m concerned, that show is finished. It doesn’t mean anything to me. I don’t watch it anymore, and I have no interest in going back at all. Danny [Aykroyd] hasn’t set foot in Studio 8H since he left, and that’s probably the way I’ll be. I was there once since I first left, and that’s it. I’d rather do movies. More people see movies anyway. I mean, people in Japan don’t see SNL, but Trading Places was a big hit there. I don’t care about doing TV anymore. Not as a performer, anyway. On SNL, we probably had more freedom to do and say what we wanted than any other show, and there were still a lot of things we couldn’t do or say. You just get tired of running up against that, the censors telling you, “You can’t say that.” Or “We’ll let you do this if you take that out.” It’s not like anybody was trying to say “fuck” on air or something. I know there’s lots of money to be made in TV production, and I’m trying to get my company, Eddie Murphy Productions, involved so we can pick up some of that money. We’re doing some stuff for HBO, but we haven’t got any network things going yet. Speaking of networks, did you know that Bill Cosby once called me up and told me he didn’t like my act?

MITCHELL: What didn’t he like about it?

MURPHY: Don’t know for sure. He never saw it. He said he heard about it from somebody he knew.

MITCHELL: Did he say your act had too much profanity? Did he give you some advice?

MURPHY: He only said that if I wanted to see how it should be done, I should come down to Lake Tahoe. I have a lot of respect for Cosby, especially as an actor. I liked him in those movies he did with Sidney Poitier. I talked with Sidney once about working with him. That guy is huge, man. I had no idea how big he was until I met him. It’s great to listen to him and watch him do Sidney Poitier in front of you. I was just watching Raisin in the Sun, and he was doing the same thing when he talked. It’s like [he stands and imitates Poitier’s stiff-necked posture and soft but powerful voice] “Willie! Willie! You spent the mon-ay…Not that mon-ay, man.”

MITCHELL: You started on SNL with [producer] Jean Doumanian at one of the worst times in that show’s history. Could you tell that you were taking part in an unmitigated disaster??

MURPHY: No, not at all. I was only 19 years old when I started on that show, and if it didn’t work out, so what? My life wasn’t going to come to an end. I auditioned for SNL and made the cast. But I was only a featured player when I started the show. I was just having fun being on television. I was in community college for a while, but I knew I was wasting time there. School wasn’t what I wanted to be doing. I don’t think SNL seemed like it was a disaster to any of us at first. But I even came out of that fine. I’ve really been pretty lucky. The worst tragedy ever to happen to me was when I lost my father.

MITCHELL: What was that like for you?

MURPHY: It was fucked up, man. I was eight. But I’ve had a good life. That’s why all these comparisons to Richard Pryor piss me off. He’s had a tough life. He’s been through a lot of shit I’ve never had to face. And I’m here because of him. He paved the way for me. I grew up listening to all those albums. I heard them so much I could recite them backwards and forwards. I would sit in that basement for hours and listen to That Nigger’s Crazy and Bicentennial Nigger and go out and do stuff from those records for my friends. People call me a genius, but he’s the real genius. It was great listening to all that stuff, because it was like I knew I was doing something I shouldn’t be doing. But it was brilliant comedy.

MITCHELL: Did you ever see him live?

MURPHY: The first time I saw his at was right after the fire. It was the only time I’ve ever done something like a critic would. I sat up there with my notebooks and I was ready to take notes. Because by that time, I was doing my stand up act, and I was curious to see how his act compared to mine. And I could see what he was doing, how he was moving the audience around by working his feelings out in front of them. Nobody does anything like that. But it was like whatever he said, the audience just loved him. I’ve seen the reverse happen with him too. I’ve seen him go out and try some new material at the clubs, when the crowd is ready for “Richard Pryor.” And his material is new and different and raw, and the audience just sits there, like, “This ain’t funny.”

MITCHELL: Would you ever like to work with him?

MURPHY: Yeah. But I know that when we get together to do something, it will have to be so funny it kills. We’ll have to be ruthless. People will be expecting so much from us, we’ll have to go in and do it hard.

MITCHELL: You’ve mentioned your social conscience in the past. How does it manifest itself?

MURPHY: I try to devote part of my time to helping. This year Coretta King asked me to participate in an event celebrating Dr. King’s birthday, but I wasn’t able to, and that bothered me a lot. Dr. King has always been a hero of mine. I couldn’t be a pacifist the way he was. If somebody calls me a nigger or gets up in my shit, I’ll hit him. I’m a man. You don’t pull that shit on me. I’m not with that “turn the other cheek.” I wish I was. As far as my social conscience goes, I know I’ve got a responsibility to kids because they really look up to me. I don’t drink and I don’t do drugs, and I make sure that gets out. That’s why it bothers me when rumors get out that I do drugs and I drink. It means a lot to me that kids who follow me know about the way I handle my life. We’re at a point where there are black guys my age—young black guys—who have a big influence on the way kids think.

MITCHELL: Guys like Wynton Maralis?

MURPHY: Wynton Marsalis wasn’t exactly who I had in mind. I was thinking about people like me and Prince and Michael Jackson. You can’t tell me a whole bunch of kids hang out and say, “I sure wish I could be like Wynton Maralis.” You know, teenaged kids pay a lot of attention to Prince, Michael, and me. It’s funny you bring up Wynton Marsalis, though. He’s one of the few black guys who sends me running to a dictionary every time I read an interview with him. He’s a really intelligent guy.

MITCHELL: Wynton probably wouldn’t be too approving of your music. He’s very critical of the whole current R&B idiom. His attitude about it even caused a rift in his relationship with his brother Branford when Branford took off to work with Sting. Wynton thinks jazz is important because it’s music that takes effort and makes you think.

MURPHY: [Laughs] How can music without any words make you think? I listen to jazz when im doing something else. I use it for background music, I don’t just sit down and concentrate on it. Lyrics, words—that’s what makes me think. It bothers me that he says that kind of stuff about other musicians. Between that and the things he says about his brother in public, I think he must really be insecure about his talent. A secure person wouldn’t have to talk like that. I ran into Branford not too long ago, and I called him a “buppie.” He said, “That ain’t me. That’s guilt by association.”

MITCHELL: When you were preparing to work on your album, How Could It Be?, there was a flood of announcements that you’d line up an all-star stable of producers: Rick James, Prince, Stevie Wonder. But you ended up working with only one of those guys, Rick James, who did “Party All The Time.” What happened?

MURPHY: Egos, man. If I had done the album with all of those guys and it had been a success, people would have said, “Yeah, it’s good, but who couldn’t have made a good record with Prince, Stevie, and Rick?” And if it was a flop, people would say, “Damn, not even Prince could save that fucked-up shit.”

MITCHELL: Well, you couldn’t have been too happy with How Could It Be?; your single sounded thin and forced.

MURPHY: [nods] Yeah, a lot of it turned out bad. But you heard my new demos.

MITCHELL: I was surprised your voice sounded so substantial.

MURPHY: Because I’m doing the kind of music I want to be doing. Like on “How Could It Be?”, when I sang that, I was embarrassed. I shouldn’t be singing ballads. I’m not good at them, and I don’t like doing them. About the only thing I was happy with was “C-O-N Confused.” The songs I played for you, those demos, they’re hard funk songs. Some are like ‘60s pop. But there aren’t many ballads. Good, up music. That’s what I like doing. I want to get Quincy Jones to produce them so we cant just go out and kick some ass, make good-time music.

MITCHELL: Why did the album How Could It Be? end up sounding like it did?

MURPHY: Because I wanted to get a producer who was enthusiastic but not a big name, someone who wouldn’t overpower things. So I got Stevie Wonder’s cousin and we did it at Stevie’s studio. But he wasn’t that familiar with the recording equipment we used; he didn’t see to it that the material got handled right, and that’s why it came out like it did. I don’t want to blame any one person for it, though. I could’ve stopped it an time. It was expensive to make too. You’d be surprised how expensive shit can be. It cost over $500,000. But it went gold and sold over 800,000. Imagine how well it would have done if it had been handled better. The next time around, I’ll just have to be bad.

MITCHELL: What about the comedy albums? You haven’t released one in awhile.

MURPHY: You know why I haven’t done any more comedy albums? Because I made a bad deal. I made a five-record deal, and I don’t see the kind of money off them that I should. So I don’t do them anymore.

MITCHELL: How often have you been in the kind of position you were in with How Could It BeHhow many times have you been involved with something that starts off well and ends up totally different—worse—than you imagined?

MURPHY: You mean like The Golden Child?

MITCHELL: As long as you bring it up, sure.

MURPHY: I’m not going to try and blame somebody else for the way that movie turned out. I wanted to do something different, a departure from the kinds of stuff I had been doing. And I didn’t get any credit for that. It like I was being told I shouldn’t try to do different things. It was not liked by the critics. But I have a theory about that. Let me try something out on you: Let’s say that there’s a movie that begins with a guy running through a mountain that’s full of traps. Then he slides down the side of the mountain while Indians shoot arrows at him. He gets in this plane and escapes, and when he does, a python comes out of the bottom of the plane.

MITCHELL: You just described the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

MURPHY: Right. And in another part of Raiders, he jumps on a submarine and rides it to another part of the world. He rides on the outside of the submarine across the world?! I don’t remember any critics making a big deal out of it, and that was some stupid shit. But check this out: In Golden Child you had a black man that was not only a realistic sexual presence but who saved the world. From the devil. Not the day, but the world. I think it was a subconscious thing with a lot of white critics. I really feel, on some level, white critics had a hard time dealing with that.

MITCHELL: Really? I just thought critics responded the way they did because they expected more from you. I know I figured Eddie Murphy would have more presence of mind than to choose to appear in a badly handled mix of fantasy and action.

MURPHY: Okay, I’m with that. But I still think it was a deeper psychological thing on the part of some critics. I just don’t go along with the whole critic’s thing of trying to analyze what this is and what it’s not and why it’s not funny. Something is funny when people laugh at it. And when they don’t, it’s not. But I don’t want to make a big deal of this. I’ve got everything I could ever want. I’m a 26-year-old heterosexual who’s never… what a minute [he rises, spots a wooden cabinet, walks to it and raps on it theatrically]… who’s never had a venereal disease. And I’ve slung my share of dick around in my time. I couldn’t have my life go any better. Right now, for example, I’ve got David Bowie coming over here to listen to some of my music.

MITCHELL: I’d like to stick around and meet him, but I know he doesn’t like the press.

MURPHY: He called earlier, and when I said I was talking to you, he said [slipping into a perfect, effete Bowie impression], “I guess I hadn’t ought to come by now, then.” [Laughs] Why don’t you stick around and meet him? Just don’t say [he drops his voice an octave into an officious tone], “Hi, David. I’m with the press.” He’ll think you’re just another nigger hanging around the house.

MITCHELL: Do you ever reflect on the circles you travel in and just trip out over it?

MURPHY: I don’t, because, like, I’m just a man. I think people are reacting to something else when they see me. They’re not reacting to me, Eddie Murphy. They don’t even know me. It’s just luck and the God in me they’re reacting to. I can understand people getting nervous around doctors or something. Like I took some of my watches in to get them fixed. The repairman reached out to shake my hand, and he was shaking and his hand was all sweaty. I don’t understand that. I can’t think of anybody I would act that way around.

MITCHELL: You’re a star. People want to know about you because you’re funny and likeable and, now, with the movies, bigger than life.

MURPHY: Since I started doing movies, I’ve noticed that people react differently to me. When I was on SNL, people would walk up to me and talk to me like they were old friends of mine. Now that I’m just doing movies, they act nervous, like they don’t know what to do around me. Because they can’t get to me in the same way, all these rumors get started. Like that I’m gay.

MITCHELL: You’ve said some pretty controversial things about gays.

MURPHY: I don’t have anything against faggots…. Ooops. [Laughs] I know gays, and I’ve made some jokes, but I wasn’t trying to be vicious or mean. That is why I don’t want to be out in the spotlight all the time. I want to move on to other things. I want to keep concentrating on my music. I know it’s not always going to be important for me to be in front of the world. That’s why I always keep my boys around. They keep me real.