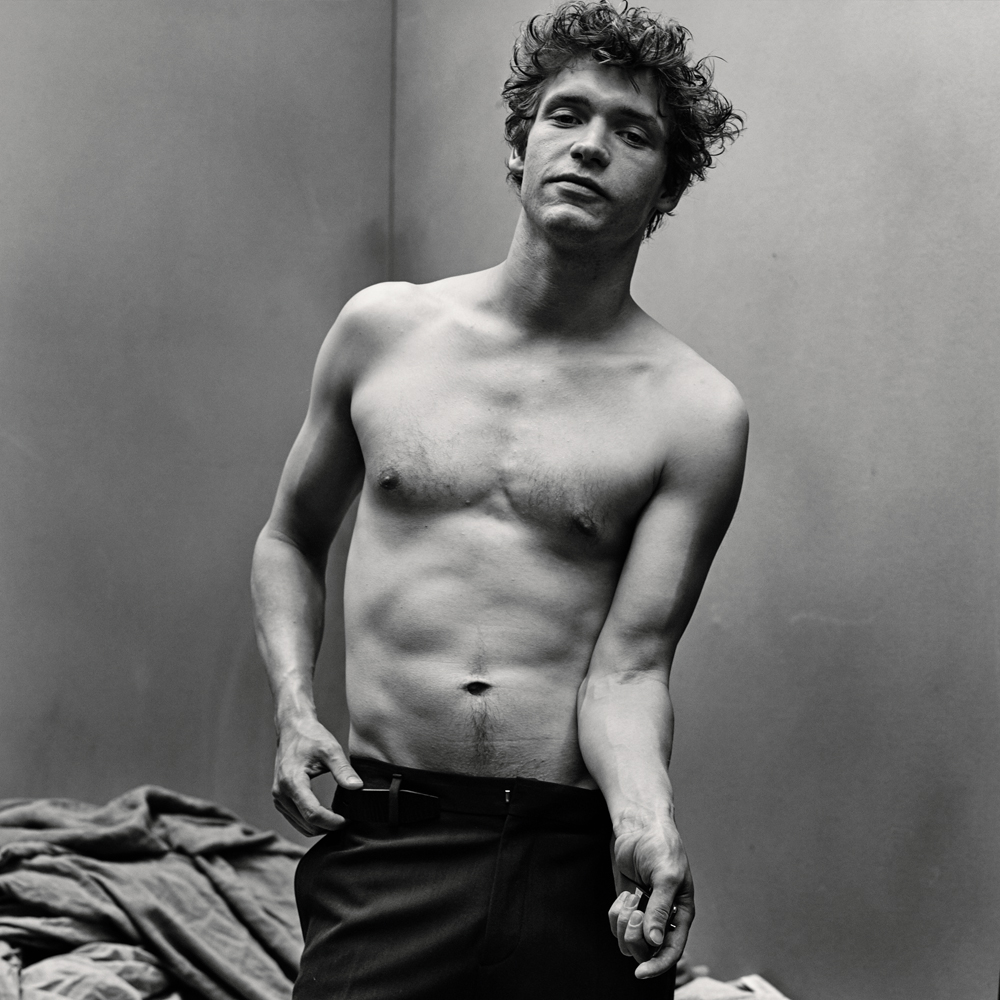

Billy Howle

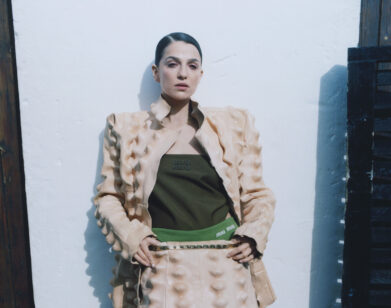

BILLY HOWLE IN NEW YORK, APRIL 2015. PANTS AND BELT: TOM FORD. STYLING: KARL TEMPLER. COSMETICS: DIOR, INCLUDING DIORSKIN NUDE AIR HEALTHY GLOW ULTRA-FLUID SERUM FOUNDATION. HAIR: JAMES PECIS/D+V MANAGEMENT. MAKEUP: PETER PHILIPS FOR CHRISTIAN DIOR. MANICURE: YUKO TSUCHIHASHI FOR DIOR VERNIS/SUSAN PRICE NYC. SET DESIGN: STEFAN BECKMAN/EXPOSURE NY. PRODUCER: SARA ZION FOR PRODN/ ART+COMMERCE. PRODUCTION MANAGER: ASHLEY SCOTT FOR PRODN/ ART+COMMERCE. RETOUCHING: GLOSS STUDIO. DIGITAL TECHNICIAN: NICHOLAS ONG. PHOTO ASSISTANTS: SIMON ROBERTS, HUAN NGUYEN, MARU TEPPEI, AND DEAN PODMORE. STYLING ASSISTANTS: MELISSA LEVY AND ALEKSANDRA KOJ. HAIR ASSISTANT: ADLENA DIGNAM. MAKEUP ASSISTANTS: EMIKO AYABE AND TALY WAISBERG. SET DESIGN ASSISTANTS: MAX ZINSER AND YONATAN ZONSZEIN. PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS: KAIA BALCOS AND JOHN DANIEL POWERS. SPECIAL THANKS: SOHO LOFTS.

“People always use the phrase in character,” says British actor Billy Howle. “You are a performer—you’re always cognizant of the fact that everything you’re doing is heightened, and it has to be.” Howle is not a method actor, but you would never know it from watching him on the stage or screen; whether as a farm boy embroiled in secrets and murder in the British television series Glue or a 19th-century painter succumbing to disease in the Almeida Theatre’s production of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the 25-year-old brings an earnest empathy to each of his roles.

Growing up in Scarborough, England, with a schoolteacher mother, a music professor father, and three brothers, Howle had a readymade audience for his dramatic impulses. “As a child, I was bouncing off the walls,” he says. “Any opportunity to dress up in other people’s clothes, wear hats or wigs, put on performances for people, create puppet theaters,” Howle took advantage. It was doing community theater as a teenager, however—particularly creating workshops for children with behavioral difficulties and special needs—that truly sparked Howle’s passion for acting. As a result, Howle enrolled at Jeremy Irons’s alma mater, the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School. “I decided to learn the conventions of classical theater so I could then bend the rules later on,” he says. In the two years since he graduated, Howle has booked some impressive roles: In addition to Glue and Ghosts, he also appeared in the miniseries New Worlds with Jamie Dornan. This summer, he will begin shooting his first film, an adaptation of Chekhov’s play The Seagull, in which he will star as Konstantin, opposite Annette Bening and Saoirse Ronan.

EMMA BROWN: Do you come from an artistic family?

BILLY HOWLE: Yes, my mum and dad are still together and they’re both very creative. My mum taught at comprehensive schools and kind of troubleshooted in classes for kids who weren’t perhaps doing as well as they could be doing. So that, in itself, I think, is quite a creative skill. It requires a lot of thinking outside the box. My dad is a professor at Kent University —electroacoustic composition, 20th century composers, and that sort of thing. One of my brothers is a classical guitarist. My older brother is a graphic designer. Then my youngest brother is this a, I want to say jack of all trades, but he’s more a master of all trades—he seems to take to something really, really well. He’s also really interested by acting. There is this weirdly uncanny resemblance.

BROWN: Oh really?

HOWLE: I went to see him in this play. He’s like six foot two or something, so he’s taller than me, but looks not too dissimilar to how I did when I was 15. He has this angst, but it’s quite a mature angst. He’s riding against something that feels unjust, and I feel like I can definitely relate to that at 15.

BROWN: That’s nice that you can be close because that’s quite a big age gap.

HOWLE: Yeah, it is. But you wouldn’t think it to sit down and talk to him. He can really hold his own in most social settings; he’s a very switched-on kid.

BROWN: You thought about going to university to study English, correct?

HOWLE: I did consider it. I tried to go to college in the UK a couple of time, but at that point I think I was a little disillusioned with education. It wasn’t giving me what I wanted it to. I needed freedom to create and do the things that I wanted to explore, and it wasn’t really doing that: it was still very prescriptive. I think I was already ready to move on to university and really specialize in something, perhaps. I went back to my local theater, the Stephen Joseph in Scarborough, and worked with community-based theater projects. We did clowning workshops, drama therapy-type things, mask stuff. I had done acting as a kid, but I became a lot more serious about it. So I went to the Old Vic Theatre School in Bristol for three years. [Before that] I did one year at another drama school as a foundation, and then came back and did more community theater. It still felt very much indulgent and very much about me, and I don’t believe that acting is that. I feel like I’m a professional storyteller, really. A lot of people say “a truth teller,” and, if the writing supports it, that’s what your aim is: to try and present people with a series of truths, and then they can make up their mind about those and whether they have any real credence or weight.

BROWN: Glue and Ghosts are both great projects. Have you ever had that pressure where you take a job to get exposure, or just to be working?

HOWLE: Sure. [laughs] You come across scripts where you’re very aware that a writer has a remit too, and sometimes that’s box-ticking for them, and I’m sure that’s soulless, and I’m sure they’d prefer to be working on something that they’re truly passionate about. We know that, in the same way that artists have to create mug prints or tea cloths or whatever—they have to do that so that they can then create the work they really want to. Someone once said to me that sometimes you’ve got to do the crowd-pleasers. I feel that writers also fit into that, and they also have to do the stuff to pay the bills in order to survive. So occasionally you’ll come across a piece of writing and it could be full of exposition and it’s very formulaic and doesn’t inspire you to want to do it. But it is a collaborative art form—I believe it’s a pure art form, acting in itself—and the art of making TV, making film, making theater, depends on every component and every participant. The true art is being able to take whatever the writer’s done, and if it is a bit flimsy or it is a bit rushed or is just box-ticking writing, then the true artist would be able to make that come off the page and sing for an audience, or a viewer. I’m still learning how to do that properly. It’s about negotiation—that’s what most collaboration is.

BROWN: You mentioned you started auditioning professionally before you had officially left drama school. Did you have an agent?

HOWLE: Yeah, I had already casually signed with an agent, and was travelling from Bristol to London at five in the morning to get to an audition for nine. I was being almost like a zealot—being really vigilant with when I travelled, and being really prepared.

BROWN: What were you like as a child?

HOWLE: I was mad. I feel like I still have that energy to a certain degree, it’s much more nervous and self-conscious now. I was fascinated by performing, definitely. I had that extroverted energy and I always involved myself in quite adult conversations. My mum never hid us from that. There was never a kid’s table; we were never treated as kids, per se, because I don’t think she believes in that.

BROWN: Did you believe in Father Christmas as a child?

HOWLE: I think we all have this kind of “Howle cynicism,” and that happens quite early on. You can imagine what it was like for my youngest brother, having three older brothers, and him still believing in Father Christmas. We we were constantly picking on him for things like that—playing small tricks. I think we were always interested in the fact that my mum always put out this brandy and this mince pie and carrots. We were fascinated by the brandy, my brother and I. We wanted to know what it was and what it did. [laughs]

BROWN: Did you ever steal it?

HOWLE: I think we did try it. But my parents have kind of a European outlook on things like that, in the sense of allowing you to sample things at a younger age in the safety of your own home. I think exclusivity is a pretty dangerous thing.

BROWN: Did you ever have an imaginary friend?

HOWLE: I was always quite jealous of my older brother Sam because he had an imaginary friend that I think he fully believed in. It was quite magical to me. I tried to have one myself, but I couldn’t do it. I tried to picture it and see what they may look like. My brother once described it to me, and I wanted to join in the game, so I created this character almost arbitrarily that was walking beside me. But mine was quite dark and elusive, and because it was so dark and elusive I kind of gave it a miss. It was like, “I don’t know if I want to get to know this guy, Sam” and he was like, “Why? It’s great!” My older brother used to run off through the woods on these long walks with his imaginary friend. Because we’re so close in age—we’re two years apart—we kind of grew up together and the imaginary friend was a spanner in the works for me. [laughs]

BROWN: I like that you created this imaginary friend who didn’t really want to hang out with you.

HOWLE: I think in my brain I was trying to be the imaginary friend. I was more interested in me doing that than creating someone else. Whereas Sam is a much more a pictorial, visual person, which is why he graphic designs.

For more from our New Wave portfolio, click here.