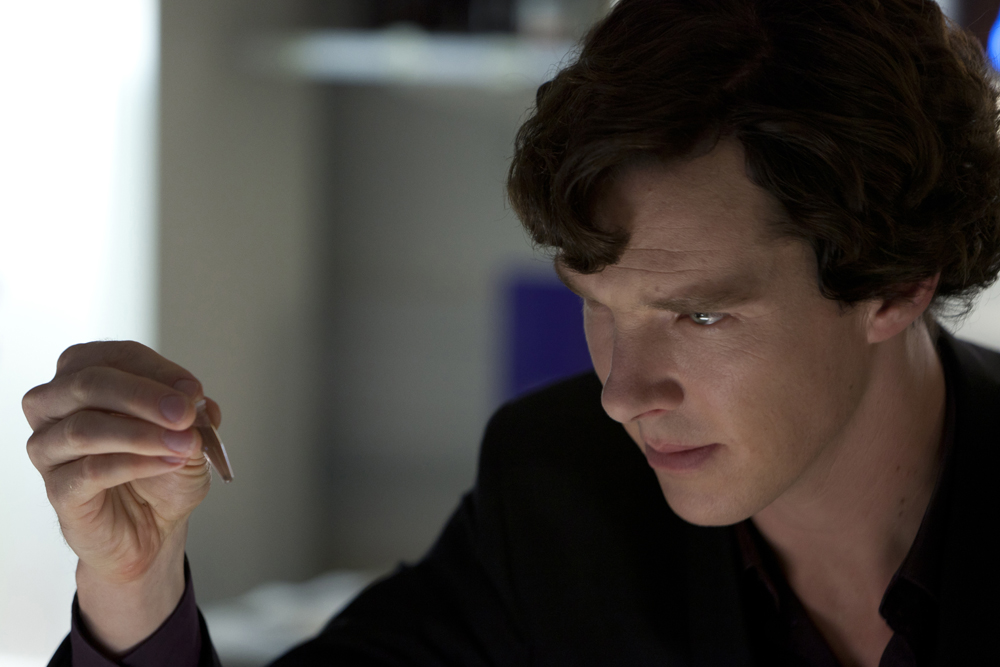

Benedict Cumberbatch

IT STILL MAKES ME GIGGLE THAT I’M PAID TO ACT.Benedict Cumberbatch

Benedict Cumberbatch’s transformative powers are such that he is not only among the busiest actors working today, but he has also attracted a very particularly, but increasingly numerous, rapturous legion of female fans—many of them seduced by his performances in Comic Con-friendly fare such as Star Trek Into Darkness (2013), the BBC series Sherlock, and Peter Jackson’s Hobbit films, referring to themselves as “Cumberbitches.” (@Cumberbitches‘ gleeful description on Twitter: “The most glorious and elusive society for the appreciation of the high cheek-boned, blue-eyed sex bomb that is Benedict Timothy Carlton Cumberbatch.”) Cumberbatch, though, undergoes perhaps his most radical metamorphosis yet (the emphasis on radical) to portray notoriously prickly information-liberation warrior and WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in Bill Condon’s new film The Fifth Estate. Based on two books—Daniel Domscheit-Berg’s Inside WikiLeaks: My Time With Julian Assange at the World’s Most Dangerous Website and WikiLeaks: Inside Julian Assange’s War on Secrecy by British journalists David Leigh and Luke Harding—The Fifth Estate focuses on the early days of WikiLeaks, charting the formation and subsequent breakdown of Assange’s relationship with one-time deputy Domscheit-Berg (played in the film by Daniel Brühl), who left the organization after clashing with Assange as pressure mounted following the release of the enormous cache of documents and files supplied to WikiLeaks by U.S. soldier Bradley Manning. (Manning was convicted on multiple counts, including violations of the Espionage Act, in July of this year and has changed his name to Chelsea in accordance with his decision to live as a woman.)

After reading an early draft of the script, Assange, who has been holed up in the Ecuadorian embassy in London since 2012 as he fights extradition to Sweden to face sexual-assault allegations, has called the film a “mass propaganda attack,” and in September, just prior to the film’s release, WikiLeaks released a memo calling it “irresponsible, counterproductive, and harmful.” Assange even went so far as to write a letter in response to Cumberbatch’s request to meet with him, in which he implored the actor to quit the project, saying, “I think I would enjoy meeting you … I believe you are a good person, but I do not believe that this film is a good film … I believe that it is going to be overwhelmingly negative for me and the people I care about. It is based on a deceitful book by someone who has a vendetta against me and my organization.”

For his part, Cumberbatch, who has never met Assange, found the mercurial Australian a “brilliant” and “remarkable” figure to inhabit—adjectives that Cumberbitches might very well use to describe his own impressively growing body of work. Of course, Cumberbatch’s realm of expertise extends far beyond the nerd-genre universe: The son of actors Timothy Carlton and Wanda Ventham, the 37-year-old Cumberbatch boasts an extensive résumé of award-winning film, theater, and television work, including more recent turns in Steven Spielberg’s War Horse and Tomas Alfredson’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (both 2011). He will have transfigured himself on screen at least three more times before year’s end, appearing as a slave owner in Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave, based on Solomon Northup’s 1853 memoir; as mousy “Little” Charles Aiken in the film adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize- and Tony Award-winning play August: Osage County; and as the Necromancer and the dragon Smaug in The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug.

Cumberbatch, who was in London, recently reconnected by phone with his Tinker, Tailor co-star Gary Oldman, who was on a fishing trip in western France.

GARY OLDMAN: Can you hear me, Cumby? I have a slight hiss on the line, but I’ll battle through it.

BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH: You sound distant.

OLDMAN: I’m in Saint-Martin-de-Ré on a fishing trip.

CUMBERBATCH: Oh, how lovely and amazing.

OLDMAN: I’m with my family and we’re getting ready to do a bit of sea fishing.

CUMBERBATCH: Oh, I’m so jealous.

OLDMAN: Anyhow, I’ll speak up.

CUMBERBATCH: Project!

OLDMAN: I will use my big voice. As my old teacher used to say, “Let’s hear that nice, big, third-year voice.” Well, good morning.

CUMBERBATCH: Good morning interviewer.

OLDMAN: Let me kick off with this one … [noise] Hello? Hello?

CUMBERBATCH: Sorry, Gary. I missed that. We went through a tunnel. [both laugh]

OLDMAN: Can you hear me okay?

CUMBERBATCH: Yeah, really well now. Can you hear me all right?

OLDMAN: Yeah. I had to walk down to a dock. I’m now on a boat.

CUMBERBATCH: [laughs] I love it.

OLDMAN: Anyhow, I wanted to kick off with a story about John Lennon that’s related to a question that I had for you: There’s a story about how Lennon once went to the cinema to see an Elvis Presley movie. Every time Elvis came on the screen, the girls in the audience would scream, so Lennon looked at Elvis up there and thought to himself, “That’s a good job. I want to do that job.” My question for you is this: Was there a transformative moment when you were either watching something or acting in an early play, and you said, “I test positive for the theater disease”? Was there a moment like that for you?

CUMBERBATCH: Well, there were a couple of clues or moments when the pieces of the jigsaw started falling into place. The first one I’m only slightly conscious of—it’s more a collective memory of my parents because I was quite young—was when I went to visit my godmother, who was at Stratford at the time, and she let me stand on the stage. I just remember looking out into the darkness, and it pulled me in, rather than pushed me away, if you know what I mean. It gave me a real energy and thrill to think about communicating with that, rather than turning away and going home and having a cup of tea and leaving it to someone else. And as adults, they just looked at each other with raised eyebrows, all three of them actors, and went, “Oh dear.” [laughs]

OLDMAN: “He’s one of us.”

CUMBERBATCH: “He’s one of us—oh, shit.” I had parents who were working actors, who did really well in their careers, but it was a living. So it was a reality for me growing up; it wasn’t a fantasy. It wasn’t sitting there going, “I want to be adored.” It wasn’t that at all. Not to say that the screams of fans aren’t a smile-raiser, but that was never the pull for me. So that’s another one off the list of comparisons between me and John Lennon. [laughs] And then I think another moment was further down the line. Basically, at school I had quite a chaotic energy; my focus was all over the place.

OLDMAN: You were probably creative. The French would say, “You were on the moon.”

CUMBERBATCH: Yeah, I’m on the moon. Exactly.

OLDMAN: Dreaming.

CUMBERBATCH: Yeah, a bit of a dreamer. But my teachers would have probably called it something like ADD, or just a pain in the ass. But the more inspirational or far-sighted teachers gave me a focus, and that was parts in plays. I had to win them, though—it wasn’t just because I was the son of Wanda and Tim. I could have been rubbish. It’s not necessarily in the genes. But my teachers saw my energy and thought, Well, maybe if we give him a focus, he might run with the ball. And they were absolutely right. So now I get to be Elvis. It still makes me giggle that I’m paid to act, let alone doing the kind of work I’m doing at this level and having actual choices. I’m in this tiny percentage of our workforce that actually gets work, let alone the kind of work I’m getting.

OLDMAN: It’s a ridiculously small percentage. When I first started, people would say that 98 percent of the profession are out of work at any one given time.

CUMBERBATCH: Yeah. I think with my parents’ generation, it was still seen as a bit of a specialist skill. It was at the cornerstone of the birth of the working-class actors that came up through the Royal Court Theatre like yourself.

OLDMAN: Yeah. It was all about French doors.

CUMBERBATCH: And living-room dramas. I mean, it wasn’t an open-and-shut job, there was still competition. But my dad himself would have said it was a lot easier.

OLDMAN: There was more work.

CUMBERBATCH: And there was more work and more of a bridge to how a career could begin, with rep and theater work, a little bit of telly, some film and radio. But the generation now below me were born into a world where if you’re a kid with raw talent now, you can roll in and land a lead in a Scorsese film. You don’t have to have prove yourself by working up the ranks, doing the classics, and getting the canon under your belt in the way the great Sirs and Dames of mom and dad’s generation—the [Ben] Kingsleys and [Helen] Mirrens and [Anthony] Hopkinses and people of that ilk. It makes it sound like some dodgy ritual, but another main moment for me was when my dad gave me his blessing. I had just played Salieri in a university production of Amadeus, and he looked me in the eye and grabbed me by the shoulders and said, “You’re better now than I ever was or will be. I think you’ll have a wonderful life and career as an actor, and I can’t wait to be a part of watching it.” And I pretty much burst into tears. What a huge thing for a man to say to his son. I mean, not only an actor to an actor, but to give me that sort of, “I bless this ship and all who sail upon her” kind of a message … How did your parents react to what you were interested in? Did they give you their blessing?

OLDMAN: Well, my dad wasn’t around. When I decided that I might want to do acting for a living—I don’t know where it really came from since there was no school play or any of that—my mom gave me her blessing. I had to get a scholarship—that was the only way I could have gone to drama school. But she didn’t say, “That’s ridiculous,” or “You can’t be serious. Don’t do that.” But I do remember watching Malcolm McDowell on TV one night, and it was like what alcoholics call a spiritual awakening, a moment of clarity. I went, “Oh, god, I want to do that.”

CUMBERBATCH: I had many moments like that. I remember watching [Kenneth] Branagh’s Hamlet at the Barbican or The Madness of King George at the National. I remember watching things of brilliance on TV with my parents, who would scour for the good stuff. We’d often sit around, maybe with one of their friends, like Donald Pickering, and talk about it, and we’d try to get him to shut up because he’d always be going, “Oh, darling, what’s she doing?” [laughs] But it felt, to me, like an event, and it drew me out of where I was and into that world. I was also brought up in a very traditional, text-heavy, educational environment, where reading and the word and the script—”The play is the thing”—was my schooling, as well as my training. You know, I did classical theater training. It was only a year, but it reinforced what I always thought the whole deal was: theater first, then a bit of telly, and then possibly film—if you’re lucky. And hopefully some radio work to use the pipes in that medium because I do love radio. But I always came at it from text.

OLDMAN: Well, when you talk about the great actors and the great giants of writing who wrote the texts of the canon, as it were, there is something to that idea of working one’s way up from being an assistant stage manager to leading man and getting to move through those texts. You know, a student once asked Stella Adler if she thought that Marlon Brando was the greatest actor in the world, and her response was, “We will never know.” [Cumberbatch laughs] She always saw the measure of great acting in the way you’d see a conductor conduct the great symphonies or a pianist play the great concertos or a dancer dance the great choreographies. It’s easy, though, to get seduced by cinema.

CUMBERBATCH: I think what I loved in cinema—and what I mean by cinema is not just films, but proper, classical cinema—are the extraordinary moments that can occur on screen. At the same time, I do feel that cinema and theater feed each other. I feel like you can do close-up on stage and you can do something very bold and highly characterized—and, dare I say, theatrical—on camera. I think the cameras and the viewpoints shift depending on the intensity and integrity of your intention and focus on that.

OLDMAN: I love the simple poetry of theater, where you can stand in a spotlight on a stage and wrap a coat around you, and say, “It was 1860 and it was winter …”

CUMBERBATCH: And you take people with you. It’s incredible, that direct feeling of communication. I have much more of a problem sitting in my own audience for a film—I always find that uncomfortable. I know most actors do, especially on first viewing. I think by the third time I saw Tinker, Tailor, it was wonderful, I could sit back and really enjoy the film and enjoy what I was part of and not get too upset about seeing myself on the screen. That’s not mock humility, or me stumbling around and mumbling, “Oh, thank you,” and looking at my feet. I’m very proud of the work I do, but I genuinely can’t involve myself with an audience as early as somebody who’s not part of the film can. So there’s that side of theater that appeals to me, where you give something and the response to what you’ve created is a communion between you and the dark that contains however many people. It’s thrilling not having a reflection other than through the people you’re communicating with. But people ask, “What do you prefer?” and I don’t have a preference. I love them both. I really do … [Oldman is disconnected] Are you there? Have I lost you? How ironic. I’ve lost you and I’m talking into the darkness…

OLDMAN: [Oldman is reconnected] Talking into the void?

CUMBERBATCH: Literally. [laughs]

OLDMAN: The way we’ve connected this call, with you in England, me in France, and the call coming through America, the FBI—

CUMBERBATCH: Exactly. It’s the FBI’s idea of heaven, this conversation. We’re triangulating.

OLDMAN: Speaking of which, tell me about this WikiLeaks movie you’ve done, The Fifth Estate.

CUMBERBATCH: It’s based on the idea that the fourth estate is the traditional print media, but with the dawning of this epoch that we’re entering into—and we’re still trying to figure out—information can now be disseminated in a purer form. So the idea that people leak information is not just about whistle-blowers, it’s also about how audiences that receive that information can then process it. It’s raw data, it’s unedited, and therefore, it’s information that allows you to be the judge. It’s not formatted for a paper that has a political bent or a need to sell or any tie-in with commerce. It has to do with freedom of information and an openness and transparency in the behavior of government, big business, and public bodies. The whistle-blowing aspect is a huge part of that, but it’s also about questioning the rule of law and the power structures that rule our lives. And that’s why it’s called The Fifth Estate—it’s the idea of an evolution in that process. Obviously, print media has been at the forefront of policing or questioning, but this new wave of technology has arrived.

OLDMAN: Which is why a film like this couldn’t be more topical.

CUMBERBATCH: I think it will remain topical. People are saying, “Don’t you feel you’ve slightly missed the boat now that there’s been all these evolutions of the story, with Manning’s trial and with [Edward] Snowden?” Not at all. The debate started and this is just proof that it is not a question that’s going to go away. Individual human rights is a massive topic, and it’s an incredibly complex and rich debate. And I hope the achievement of our film will be to empower people—like WikiLeaks intended to—to seek out their own truth with the information we’ve given in the film—or the version of information that we’ve given in the film. While based on accounts and real events, like any film, there are compressions and events that didn’t involve certain characters that dramatically needed to be there in the film for the version of a three-year time period, from 2007 to 2010, that we’re portraying. So it’s really based on the relationship between Julian Assange and one of his critical volunteers, Daniel Domscheit-Berg, and how that relationship goes awry and why. But it spans the burgeoning WikiLeaks that was not that well known about outside the hacker community—and even within that community it wasn’t yet known as this triumphant tool that it was known as after 2010 for delivering the most shocking revelations of the “Collateral Murder” footage or the Iraq and Afghanistan war logs, or the diplomatic cables.

OLDMAN: Did you meet Julian Assange?

CUMBERBATCH: No, we didn’t meet. He didn’t want to meet because he didn’t want to condone the film, which I completely respect. In his predicament, he needs to be distanced from anything other than the truth his lawyers are seeking to harness around him—his version of events. He felt that the two accounts that the film were based on were poisonous and detrimental to his cause and the people involved in his cause, which was a hard thing to hear. It made me question what we were doing and why we were doing it, but I think we are justified, because, as I communicated to him, I think he’ll be surprised with how sympathetic the portrayal of him and WikiLeaks is. This is not a film that’s supposed to polarize people into galvanizing a one-sided argument; this is about opening up the debate, and there’s great sophistication on either side of the fence—the fence, in this film, being the U.S. State Department. But I’d love to meet the guy. I have a great deal of admiration for him, and I’ve made no secret of saying that before. I’m an actor playing him in a film, so of course I have empathy for his state of mind and beliefs. But I did my work remotely. I worked as if from a photograph rather than a life class. There’s an awful lot of material and footage about Julian. If you think there are a lot of websites about me, you should see how much footage there is about Julian and of Julian.

OLDMAN: Was he an interesting character to inhabit?

CUMBERBATCH: Oh, my god, yes. I think the challenge was to give something of him that no one has seen—which is probably, for him, going to be the hardest thing to watch. It’s me trying to reveal what isn’t in any of those interviews or his public persona. Whether I got that or not, I don’t know. He’s bound to have issue with it. But it’s a very rich tapestry, and at the center is this really enigmatic character. So to try and pin that down and inhabit someone who’s very far from me physically, emotionally, intellectually, culturally … He was brought up in Australia by a single parent and escaped a cult and has this brilliant, rebellious intellect that took him through the hacking world to become this frontman for the most extraordinarily revolutionary idea in media—this whistle-blowing website where data can be dumped anonymously and then disseminated by the public, free, and with no interference from any other intermediary. He’s quite a remarkable human being to try to pull off—to get the motivations and the instincts and emotional kind of undertones right. Most people only know him as the man who’s in his current predicament, the kind of tabloid version of him—the white-haired weirdo locked up in an embassy, wanted for rape. And actually there’s really something to celebrate about him and to explore about him, which is a lot richer than those broad brushstrokes. Bill Condon and I met, and he’s also just a brilliant man. In this film, he has made this near impossible, intellectual jigsaw puzzle. And I think it’s going to be a provoking and politically resonant, pertinent piece of work.

OLDMAN: It is a story that will continue to have legs. This is not going to go away very quickly.

CUMBERBATCH: No, not at all. I think the American public, now that they know about these debates—because of Snowden in particular as well as Manning—are now going, “Hang on a minute, why do you need to know everything I’m saying to Aunt Deidre in Wisconsin when we’re talking about whether she got the curtain tapestry right? If our right to privacy is being taken away from us, then haven’t the terrorists won?” It’s a very complex argument. Of course, we want to get the bad guys, and I think now with fundamentalists, people who treat belief with a total lack of humor or empathy for any other viewpoint than their own—they, to me, are the enemy. And those people are born out of desperate extremes. So it’s not about politics. It’s fascinating to see that the Obama administration is responding to it, and it’ll be interesting to see what England does. Personally, if they are listening to this conversation, then the principle is upsetting. It’s what they could do with the information they glean from a harmless conversation that isn’t about what they’re listening in for—I think that’s really the rub. But they have closed down terror networks and it’s increasingly difficult for them because of mobile communication. It makes you think that their job is impossible. And if they’ve saved innocent civilian lives through monitoring our phone calls, then am I really that upset that someone knows I talked to you about acting and process or ordered a sandwich or been belligerent about something to someone? If we’re talking about people listening to us to check that we’re not planning a terrorist attack, then so be it. I’m not condoning it, but I can see the justifications. It’s very complex.

OLDMAN: I don’t even know what I feel about Snowden, in a way. Part of me feels that if you’re going to whistle-blow, then do it, but stand your ground. Face the consequences. Don’t run.

CUMBERBATCH: Yeah, but at the same time, he’s got a lot more information. That’s what I get a feeling of. It’s not just what he’s leaked so far—he’s got a lot more. So it’s what they could do to him. They could just lock him away and throw away the key. But we need to engage with this. It’s a reality of our lives—we need to know. Anyway, it’s so easy to get mired in this, and I’m not a soldier and I’m not a politician, and I’m not a spy—I’m an actor.

OLDMAN: Can you imagine people spying in on us now? A couple of lovies …

CUMBERBATCH: Gaffing away, talking about process and our jobs.

OLDMAN: No threat here.

CUMBERBATCH: I think we’d make great spies because of that, rather than [Guy] Burgess bumming around going, “I’m a spy,” and no one believing him. We’d be such obviously bad choices that it would kind of be a great double bluff.

OLDMAN: So, are you planning to return to the theater? [both laugh]

CUMBERBATCH: Well, right now I’m also prepping The Imitation Game, which is the film I’m doing about Alan Turing. But I’m planning to do something theater-wise next year, but I don’t know when, so I have to be a bit cagey about it.

OLDMAN: So you’ll be secretive about it.

CUMBERBATCH: Yeah, but it’s in the works at the moment.

OLDMAN: Well, as I see land receding and the ocean beckoning …

CUMBERBATCH: The call of the marlins.

OLDMAN: Let me as you one final question: So Benedict Cumberbatch, your films are on fire and you have to run in a save one scene …

CUMBERBATCH: Oh, god. A scene? Fucking hell.

OLDMAN: A scene.

CUMBERBATCH: Just my films? Or in a film in particular?

OLDMAN: Your work. What of your work would you grab from the fire?

CUMBERBATCH: Christ. That’s difficult. It’s a brilliant question, but I don’t know … One postcard moment for me, because there was such a resonance beneath it—and, Gary Oldman, this involves you—just at the end of Tinker, Tailor, where we pass each other in the office … I shouldn’t say the office; it’s not called the office …

OLDMAN: In the Circus.

CUMBERBATCH: In the Circus. We pass each other and there’s a knowing look. And just after I pass you, I smile, knowing what that means, knowing what we went through to achieve that, knowing what might be for both of us. Yeah, that moment means a lot to me. I suppose that’s definitely one of them. And there are others, but for very different reasons. Bits where I go, “Yeah, that’s okay. I can definitely live by that.” There are one or two deduction moments in Sherlock. There are moments, like, on the edge of the roof, as well, with John [Watson, played by Martin Freeman]. There is one whole scene in Parade’s End—because I love that character so, so dearly—that I would like to keep. It’s a moment in the second episode, I think, when I’m talking to Valentine, the woman I love and have a profound connection with, but I have to deny my feelings for her because of my sense of honor to my wife, my ever self-destructing, saboteuring wife. And it’s a scene where I tell her I’m going to war. It’s all a mess, but the scene is about what I am, who I am, what I stand for, what my country is. I will be very happy if they play that in my, sort of, “Here was an actor and here is something he did.” I’d be very happy about that moment being shown. Well, I’ll let you get back to your “We’re gonna need a bigger boat” moment.

OLDMAN: Yes, we’re going to need a bigger boat.

GARY OLDMAN IS A STAGE AND SCREEN ACTOR WHO HAS APPEARED IN FILMS SUCH AS SID & NANCY (1986), JFK (1991), BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA (1992), AND THE DARK KNIGHT TRILOGY. HE WILL APPEAR IN JOSEÌ PADILHA’S ROBOCOP, DUE OUT IN FEBRUARY 2014. SPECIAL THANKS: DEBBIE DAY.